Art

I’m White. Should I Repatriate My African Art?

The magazine’s Ethicist columnist on whether to return artwork to its original source.

I was privileged to have been raised in a family who prized the arts, including works from cultures that were not our own. (We are of European ancestry.) Among the art in my childhood home was a significant collection of masks, statues, figurines and other objects from mostly West African cultures. My father, who acquired these pieces in the 1970s and ’80s through art dealers, has always taken pride in the idea that they were not “tourist art.” Most of the items date to the 19th and early 20th centuries.

I have come into possession of several of these items over the years, and always appreciated them for their artistic qualities. But as my understanding of the horrors of colonialism and the legacy of slavery expands, I question whether it’s ethical for me to display a Baule mask or a Yoruba dance wand — ceremonial items with deep spiritual and cultural significance. Knowing they were not created for a tourist market also leads me to believe that at some point in their history they were probably acquired via an unfair transaction.

What is my responsibility to the descendants of the people who created these objects? Some friends have suggested donation to a local museum that specializes in African art, but this would perpetuate the colonialist attitude that these objects don’t belong where they were created. Is it possible to repatriate them? — Kate

From the Ethicist:

When I was a child in Kumasi, in Ghana, Hausa-speaking traders often visited my mother, an Englishwoman who was known to collect certain artifacts from the region. They had bought the items from villagers — often members of my father’s ethnic group — who preferred the money they were offered to the objects, typically brass weights or carved dolls. The weights had been useful when gold dust was the currency and you needed to check how much gold you were getting. Some of the carved dolls were a kind of medicine, which women carried on their backs when they wanted to get pregnant. Pregnancy achieved, you might not need the doll. And so on.

Perhaps in a just world these villagers would have been richer, and perhaps if they had been richer, they would have held onto these objects rather than selling them for the prices they were paid. But if we thought that every market transaction in those circumstances was invalid, we’d have to think that the women who bought textiles from the villages to sell in Kumasi’s central market were doing something wrong.

Many African objects that Westerners now treat as art works were sold, like the weights and carvings my mother bought, by people who had the right to sell them. Still, I’ve heard it argued that anything acquired during the colonial period (as your possessions may have been) was unjustly expropriated — that the colonial context ruled out freely made choices, even outside circumstances of overt violence. The implication is that people who sold these objects were dupes of the buyer, ignoramuses unaware of the value of what they were selling, or else intimidated into making the sale.

Careful accounts of such transactions (notably by Michel Leiris, who accompanied a French collecting expedition through Africa in the 1930s) indicate that skulduggery sometimes took place, but that it wasn’t the norm. So you have to imagine going back and telling, say, a Yoruba family with a Shango wand that they were forbidden to sell it, at least to someone from another culture. How persuasive would you be? Bear in mind, too, that many objects used in traditional rituals were seen as spiritually charged only while they were in use.

Ivory Coast has, in any case, more than enough Baule masks for the Baule to use in rituals like the Mblo dances. Nigeria certainly has more than enough Shango wands for those who want to participate in the rites of the traditional god of thunder and lightning. And because some 90 percent of Yoruba people today are either Christian or Muslim, the traditional religion of Yorubaland doesn’t have precisely the same significance as it did in the past.

Nor, finally, does the fact that you are not of African descent make it wrong for you to have these things, any more than it would be wrong for members of the historically powerful Yoruba to possess a stool from their Nupe neighbors. (Yes, West Africa’s long history, like Europe’s, features plenty of conquest and pillage.) Prizing cultural artifacts from around the globe bespeaks, at its best, a cosmopolitan sensibility — one that’s especially important in a world increasingly narrowed by nativism.

Readers Respond

The last question was from a reader who disapproved of a dead relative’s lifestyle and beliefs, but wanted to support their children. She wrote: “Recently a relative from a distant state was shot and killed in what the authorities believe was a gang-related dispute, leaving behind a spouse and young children. In the aftermath, friends and relatives of the family used a GoFundMe campaign to help with expenses. Photos have circulated on social media before and since that show my relative and their spouse and friends wearing clothing with the insignia of the gang, which is well known. Over the years, according to the F.B.I. and news reports, the gang has been tied to murders, shootings, Nazi symbolism, illegal drug trafficking and running an escort service. … I cannot support illegal and immoral behaviors that are antithetical to my beliefs, and yet I do not want to walk away. … How might I support the young children when their parent may be embroiled in a lifestyle that ultimately proves harmful to their well-being?”

In his response, the Ethicist noted: “Let’s assume your suspicions are correct. You’ll still want to be sure your actions are making things better, not worse. Involving child protective services is always a last resort, because an inquiry can itself be deeply upsetting. While being raised by the spouse of a slain gang member clearly has serious risks, you have no direct evidence that the children are not being loved and cared for. … You could simply put aside the noxiousness of the spouse’s beliefs and associations, then, and offer financial assistance in such a way that you are kept in touch with the kids through the years, so they have access to you when they’re older. Or you could set up a fund designed to be available only for the children’s specific needs (educational, medical, etc.), and aim to keep your support tightly circumscribed. You could even start a savings account so that they have money to go to college later. Ideally, the kids will grow aware of you as a dependable, caring adult in another state, while you avoid entanglement with a repugnant subculture.” (Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

In addition to the sources of support the Ethicist mentions, the letter writer could offer to fund and potentially arrange overnight summer camp for these children, if they would like. Summer camps often offer an alternative place to belong and to witness other perspectives. — Pam

⬥

There are grief therapists, centers and camps for children who have lost a close relative. The letter writer should research therapeutic services in the children’s area and offer to pay for it. She should also offer to have the children in her home for holidays. — Marie

⬥

If I were the letter writer, I would keep this family at arm’s length and watch what develops with the children’s mother. In the meantime, she can offer condolences from a distance. — Steve

⬥

The letter writer should definitely set up a fund, and a fund administrator, who will ensure the funds are only used for the children’s health care, schooling and clothing. — Susan

⬥

My brother was a high-ranking member of a notorious motorcycle gang when he died from an overdose 10 years ago. He left behind a daughter, and my family supported her without judgment or questions because she and her mom needed assistance. The letter writer should not place what she thinks are moral failings of an adult onto their young children. — Kate

Art

Calvin Lucyshyn: Vancouver Island Art Dealer Faces Fraud Charges After Police Seize Millions in Artwork

In a case that has sent shockwaves through the Vancouver Island art community, a local art dealer has been charged with one count of fraud over $5,000. Calvin Lucyshyn, the former operator of the now-closed Winchester Galleries in Oak Bay, faces the charge after police seized hundreds of artworks, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, from various storage sites in the Greater Victoria area.

Alleged Fraud Scheme

Police allege that Lucyshyn had been taking valuable art from members of the public under the guise of appraising or consigning the pieces for sale, only to cut off all communication with the owners. This investigation began in April 2022, when police received a complaint from an individual who had provided four paintings to Lucyshyn, including three works by renowned British Columbia artist Emily Carr, and had not received any updates on their sale.

Further investigation by the Saanich Police Department revealed that this was not an isolated incident. Detectives found other alleged victims who had similar experiences with Winchester Galleries, leading police to execute search warrants at three separate storage locations across Greater Victoria.

Massive Seizure of Artworks

In what has become one of the largest art fraud investigations in recent Canadian history, authorities seized approximately 1,100 pieces of art, including more than 600 pieces from a storage site in Saanich, over 300 in Langford, and more than 100 in Oak Bay. Some of the more valuable pieces, according to police, were estimated to be worth $85,000 each.

Lucyshyn was arrested on April 21, 2022, but was later released from custody. In May 2024, a fraud charge was formally laid against him.

Artwork Returned, but Some Remain Unclaimed

In a statement released on Monday, the Saanich Police Department confirmed that 1,050 of the seized artworks have been returned to their rightful owners. However, several pieces remain unclaimed, and police continue their efforts to track down the owners of these works.

Court Proceedings Ongoing

The criminal charge against Lucyshyn has not yet been tested in court, and he has publicly stated his intention to defend himself against any pending allegations. His next court appearance is scheduled for September 10, 2024.

Impact on the Local Art Community

The news of Lucyshyn’s alleged fraud has deeply affected Vancouver Island’s art community, particularly collectors, galleries, and artists who may have been impacted by the gallery’s operations. With high-value pieces from artists like Emily Carr involved, the case underscores the vulnerabilities that can exist in art transactions.

For many art collectors, the investigation has raised concerns about the potential for fraud in the art world, particularly when it comes to dealing with private galleries and dealers. The seizure of such a vast collection of artworks has also led to questions about the management and oversight of valuable art pieces, as well as the importance of transparency and trust in the industry.

As the case continues to unfold in court, it will likely serve as a cautionary tale for collectors and galleries alike, highlighting the need for due diligence in the sale and appraisal of high-value artworks.

While much of the seized artwork has been returned, the full scale of the alleged fraud is still being unraveled. Lucyshyn’s upcoming court appearances will be closely watched, not only by the legal community but also by the wider art world, as it navigates the fallout from one of Canada’s most significant art fraud cases in recent memory.

Art collectors and individuals who believe they may have been affected by this case are encouraged to contact the Saanich Police Department to inquire about any unclaimed pieces. Additionally, the case serves as a reminder for anyone involved in high-value art transactions to work with reputable dealers and to keep thorough documentation of all transactions.

As with any investment, whether in art or other ventures, it is crucial to be cautious and informed. Art fraud can devastate personal collections and finances, but by taking steps to verify authenticity, provenance, and the reputation of dealers, collectors can help safeguard their valuable pieces.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

-

Sports14 hours ago

Sports14 hours agoDolphins will bring in another quarterback, while Tagovailoa deals with concussion

-

Sports15 hours ago

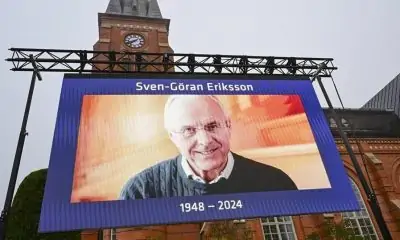

Sports15 hours agoDavid Beckham among soccer dignitaries attending ex-England coach Sven-Goran Eriksson’s funeral

-

News15 hours ago

News15 hours agoVancouver Whitecaps cautious of lowly San Jose Earthquakes

-

Sports10 hours ago

Sports10 hours agoEdmonton Oilers sign defenceman Travis Dermott to professional tryout

-

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours agoCanada’s Marina Stakusic advances to quarterfinals at Guadalajara Open

-

News15 hours ago

News15 hours agoAlberta town adopts new resident code of conduct to address staff safety

-

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours agoDavid Lipsky shoots 65 to take 1st-round lead at Silverado in FedEx Cup Fall opener

-

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours agoAlouettes receiver Philpot announces he’ll be out for the rest of season