VIENNA (AP) — Austria’s far-right Freedom Party could win a national election for the first time on Sunday, tapping into voters’ anxieties about immigration, inflation, Ukraine and other concerns following recent gains for the hard right elsewhere in Europe.

Herbert Kickl, a former interior minister and longtime campaign strategist who has led the Freedom Party since 2021, wants to become Austria’s new chancellor. He has used the term “Volkskanzler,” or chancellor of the people, which was used by the Nazis to describe Adolf Hitler in the 1930s. Kickl has rejected the comparison.

But to become Austria’s new leader, he would need a coalition partner to command a majority in the lower house of parliament.

And a win isn’t certain, with recent polls pointing to a close race. They have put support for the Freedom Party at 27%, with the conservative Austrian People’s Party of Chancellor Karl Nehammer on 25% and the center-left Social Democrats on 21%.

More than 6.3 million people age 16 and over are eligible to vote for the new parliament in Austria, a European Union member that has a policy of military neutrality.

Kickl has achieved a turnaround since Austria’s last parliamentary election in 2019. In June, the Freedom Party narrowly won a nationwide vote for the first time in the European Parliament election, which also brought gains for other European far-right parties.

In 2019, its support slumped to 16.2% after a scandal brought down a government in which it was the junior coalition partner. Then-vice chancellor and Freedom Party leader Heinz-Christian Strache resigned following the publication of a secretly recorded video in which he appeared to offer favors to a purported Russian investor.

The far right has tapped into voter frustration over high inflation, the war in Ukraine and the Covid pandemic. It also been able to build on worries about migration.

In its election program, the Freedom Party calls for “remigration of uninvited foreigners,” and for achieving a more “homogeneous” nation by tightly controlling borders and suspending the right to asylum via an “emergency law.”

Gernot Bauer, a journalist with Austrian magazine Profil who recently co-published an investigative biography of the far-right leader, said that under Kickl’s leadership, the Freedom Party has moved “even further to the right,” as Kickl refuses to explicitly distance the party from the Identitarian Movement, a pan-European nationalist and far-right group.

Bauer describes Kickl’s rhetoric as “aggressive” and says some of his language is deliberately provocative.

The Freedom Party also calls for an end to sanctions against Russia, is highly critical of western military aid to Ukraine and wants to bow out of the European Sky Shield Initiative, a missile defense project launched by Germany.

The leader of the Social Democrats, a party that led many of Austria’s post-World War II governments, has positioned himself as the polar opposite to Kickl. Andreas Babler has ruled out governing with the far right and labeled Kickl “a threat to democracy.”

While the Freedom Party has recovered, the popularity of Nehammer’s People’s Party, which currently leads a coalition government with the environmentalist Greens as junior partners, has declined since 2019.

During the election campaign, Nehammer portrayed his party, which has taken a tough line on immigration in recent years, as “the strong center” that will guarantee stability amid multiple crises.

But it is precisely these crises, ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and resulting rising energy prices, that have cost the conservatives support, said Peter Filzmaier, one of Austria’s leading political scientists.

Under their leadership, Austria has experienced high inflation averaging 4.2% over the past 12 months, surpassing the EU average.

The government also angered many Austrians in 2022 by becoming the first European country to introduce a coronavirus vaccine mandate, which was scrapped a few months later without ever being put into effect. And Nehammer is the third chancellor since the last election, taking office in 2021 after predecessor Sebastian Kurz — the winner in 2019 — quit politics amid a corruption investigation.

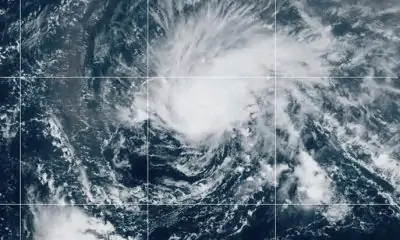

But the recent flooding caused by Storm Boris that hit Austria and other countries in Central Europe brought back the topic of the environment into the election debate and helped Nehammer slightly narrow the gap with the Freedom Party by presenting himself as a “crisis manager,” Filzmaier said.

Nehammer said in a video Thursday that “this is about whether we continue together on this proven path of stability or leave the country to the radicals, who make a lot of promises and don’t keep them.”

The People’s Party is the far right’s only way into government.

Nehammer has repeatedly excluded joining a government led by Kickl, describing him as a “security risk” for the country, but hasn’t ruled out a coalition with the Freedom Party in and of itself, which would imply Kickl renouncing a position in government.

The likelihood of Kickl agreeing to such a deal if he wins the election is very low, Filzmaier said.

But should the People’s Party finish first, then a coalition between the People’s Party and the Freedom Party could happen, Filzmaier said. The most probable alternative would be a three-way alliance between the People’s Party, the Social Democrats and most likely the liberal Neos.

___

Associated Press videojournalist Philipp Jenne contributed to this report.