Art

Alopecia in art history: The many ways women’s hair loss has been interpreted – CNN

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writers. CNN is showcasing the work of The Conversation, a collaboration between journalists and academics to provide news analysis and commentary. The content is produced solely by The Conversation.

The Conversation

—

At least 40% of women experience hair loss or alopecia over their lifetimes. This could be alopecia areata (patchy hair loss), traction alopecia (strained hair loss) or another form. The different ways that women’s hair loss has been depicted across art history demonstrates the many different ways it has been interpreted over the years.

In 16th and 17th century Britain, for example, women’s alopecia was sometimes interpreted as retribution for sins, including adultery.

Some historical art, however, depicts a more neutral, or even positive, attitude towards women’s alopecia. In religious or mythical art, it was sometimes idealized as divine.

“Madonna and Child” (pictured top), painted in the 15th century by Italian Renaissance artist Carlo Crivelli, shows Jesus and Mary embracing in a gold, stylized setting. The pair sit behind a religious altar surrounded by ripe fruit and adorned with halos. Madonna has a high forehead and her blonde hair recedes, particularly on her right temple.

This association between alopecia and divinity is echoed in a work by another Renaissance Italian artist, Cosmè Tura. His ”Madonna and Mary Magdalene” (circa 1490) depicts both mother and child with prominent foreheads.

A glazed terracotta piece created by the Italian sculptor Andrea della Robbia in 1475 features Prudence, a human embodiment of Christian morality, as a balding two-headed person.

Baldness in women has been connected to the divine for various reasons. It took the emphasis off of personal appearance in favour of deeper, more spiritual, priorities. But intentional hair removal played a role too. For some religious people, such as Buddhist nuns and Haredi Jewish wives, a bald head is thought to be purer and shaving can represent a regular, sacrificial ritual.

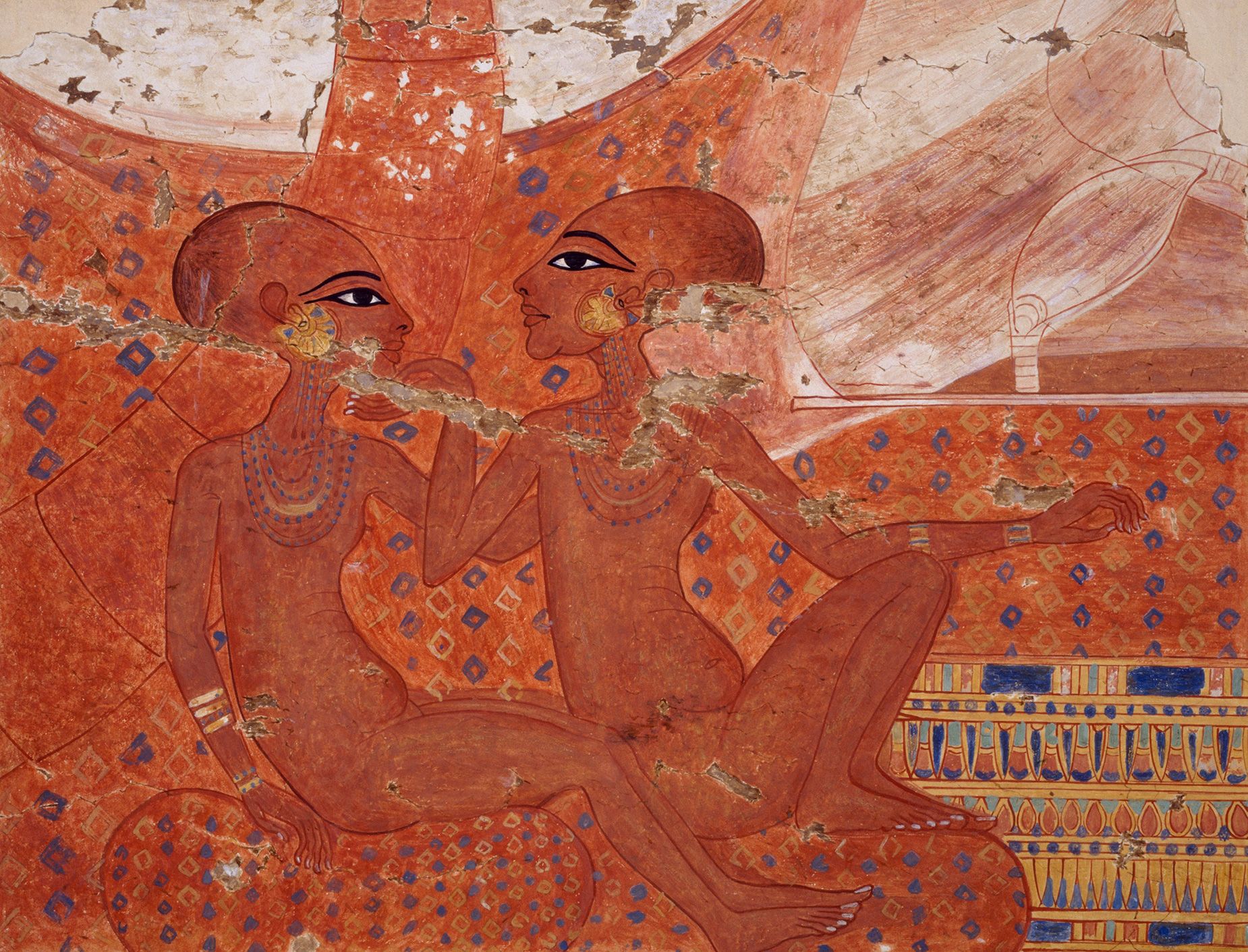

Ancient depictions

Artwork on the walls of the tomb of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh, Akhenaten who ruled from 1351 to 1334 B.C., depicts two of his daughters, naked, with bald heads. Head shaving as well as natural baldness was common among the ancient Egyptians, including women.

In fact, ancient Egyptians had distinct terms for female and male alopecia. This attests to just how common baldness, head shaving and wig wearing were for both sexes in ancient Egypt.

And it isn’t just Egypt. Partial and full head shaving has historically been common among women across sub-Saharan Africa. As one traveller observed among the inhabitants of the 18th century Kingdom of Issini (modern-day Ghana): “Some only shave one half of the head … Others leave broad patches here and there unshaved.”

Medieval and Renaissance alopecia

The 15th century painting, “Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement,” by the Italian artist, Fra Filippo Lippi, features an aristocratic profile of a woman facing a man. She has a prominent forehead and high hairline.

The appearance of recessed frontal hairlines in Medieval and Renaissance Europe may have been fashionable and even considered a sign of intelligence, encouraging customs of forehead shaving and eyebrow plucking.

The 16th century queen of England, Elizabeth I, was often painted in this way. One undated oil portrait of the British monarch depicts her in bejeweled robes, with a pearl emblazoned veil and a prominent forehead.

The removal of female bodily hair at this time, including on the forehead, wasn’t just a matter of fashion. It also arguably arose due to patriarchal ideas that women’s body hair was dirty and even dangerous to men.

Modern alopecia

Adverts and research today tend to discuss hair loss exclusively through medical terms, as a kind of detrimental disease. A recent BBC article refers to people with alopecia areata as “patients” and their experience of it as “profoundly challenging”. This certainly reflects some experiences, but not those who interpret their hair loss more neutrally, or even with pride.

Pharmaceutical and cosmetic products are promoted as “necessary” treatments. A newly licensed drug, litfulo or ritlecitinib, was hailed last month as the “first treatment” and “medicine” for alopecia. But as many forms of alopecia are not delimiting and as the “treatments” on offer have limited efficacy and potential safety issues, this should not be the default response. For example, the European Medicine Agency notes that ritlecitinib results in 80% hair regrowth but only for 36% of people taking it. About 10% are at risk of diarrhea, acne and throat infections.

Another study noted that similar alopecia drugs, that operate through immunosuppression, only seem to work if they are taken continuously, yet their long-term safety has not been established.

Depictions of alopecia throughout art history are a reminder of the many complicated ways women’s hair loss has been viewed. Sometimes weaponized as a way to shame women, sometimes venerated as a sign of the divine, the truth is that hair loss really indicates nothing about a woman’s worth, morality or status.

But historical depictions of women’s alopecia and baldness provide hope. They show that alopecia has been conceptualized differently at different times. This means the current framing of alopecia as an inevitably disadvantaging disease in need of certain “treatments” might be biased too. They suggest if our societal interpretation of alopecia improves (as something that shouldn’t be stigmatized), then so too may the individual experience (as something that shouldn’t be dreaded).

Glen Jankowski is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences at Leeds Beckett University, UK.

Art

Calvin Lucyshyn: Vancouver Island Art Dealer Faces Fraud Charges After Police Seize Millions in Artwork

In a case that has sent shockwaves through the Vancouver Island art community, a local art dealer has been charged with one count of fraud over $5,000. Calvin Lucyshyn, the former operator of the now-closed Winchester Galleries in Oak Bay, faces the charge after police seized hundreds of artworks, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, from various storage sites in the Greater Victoria area.

Alleged Fraud Scheme

Police allege that Lucyshyn had been taking valuable art from members of the public under the guise of appraising or consigning the pieces for sale, only to cut off all communication with the owners. This investigation began in April 2022, when police received a complaint from an individual who had provided four paintings to Lucyshyn, including three works by renowned British Columbia artist Emily Carr, and had not received any updates on their sale.

Further investigation by the Saanich Police Department revealed that this was not an isolated incident. Detectives found other alleged victims who had similar experiences with Winchester Galleries, leading police to execute search warrants at three separate storage locations across Greater Victoria.

Massive Seizure of Artworks

In what has become one of the largest art fraud investigations in recent Canadian history, authorities seized approximately 1,100 pieces of art, including more than 600 pieces from a storage site in Saanich, over 300 in Langford, and more than 100 in Oak Bay. Some of the more valuable pieces, according to police, were estimated to be worth $85,000 each.

Lucyshyn was arrested on April 21, 2022, but was later released from custody. In May 2024, a fraud charge was formally laid against him.

Artwork Returned, but Some Remain Unclaimed

In a statement released on Monday, the Saanich Police Department confirmed that 1,050 of the seized artworks have been returned to their rightful owners. However, several pieces remain unclaimed, and police continue their efforts to track down the owners of these works.

Court Proceedings Ongoing

The criminal charge against Lucyshyn has not yet been tested in court, and he has publicly stated his intention to defend himself against any pending allegations. His next court appearance is scheduled for September 10, 2024.

Impact on the Local Art Community

The news of Lucyshyn’s alleged fraud has deeply affected Vancouver Island’s art community, particularly collectors, galleries, and artists who may have been impacted by the gallery’s operations. With high-value pieces from artists like Emily Carr involved, the case underscores the vulnerabilities that can exist in art transactions.

For many art collectors, the investigation has raised concerns about the potential for fraud in the art world, particularly when it comes to dealing with private galleries and dealers. The seizure of such a vast collection of artworks has also led to questions about the management and oversight of valuable art pieces, as well as the importance of transparency and trust in the industry.

As the case continues to unfold in court, it will likely serve as a cautionary tale for collectors and galleries alike, highlighting the need for due diligence in the sale and appraisal of high-value artworks.

While much of the seized artwork has been returned, the full scale of the alleged fraud is still being unraveled. Lucyshyn’s upcoming court appearances will be closely watched, not only by the legal community but also by the wider art world, as it navigates the fallout from one of Canada’s most significant art fraud cases in recent memory.

Art collectors and individuals who believe they may have been affected by this case are encouraged to contact the Saanich Police Department to inquire about any unclaimed pieces. Additionally, the case serves as a reminder for anyone involved in high-value art transactions to work with reputable dealers and to keep thorough documentation of all transactions.

As with any investment, whether in art or other ventures, it is crucial to be cautious and informed. Art fraud can devastate personal collections and finances, but by taking steps to verify authenticity, provenance, and the reputation of dealers, collectors can help safeguard their valuable pieces.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

-

Sports11 hours ago

Sports11 hours agoDolphins will bring in another quarterback, while Tagovailoa deals with concussion

-

Sports12 hours ago

Sports12 hours agoDavid Beckham among soccer dignitaries attending ex-England coach Sven-Goran Eriksson’s funeral

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoVancouver Whitecaps cautious of lowly San Jose Earthquakes

-

News11 hours ago

News11 hours agoUnifor says workers at Walmart warehouse in Mississauga, Ont., vote to join union

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours agoCanada’s Marina Stakusic advances to quarterfinals at Guadalajara Open

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours agoDavid Lipsky shoots 65 to take 1st-round lead at Silverado in FedEx Cup Fall opener

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours agoAlouettes receiver Philpot announces he’ll be out for the rest of season

-

Media10 hours ago

Media10 hours agoWhat to stream this weekend: ‘Civil War,’ Snow Patrol, ‘How to Die Alone,’ ‘Tulsa King’ and ‘Uglies’