Media

Is Hunterbrook Media a News Outlet or a Hedge Fund? – The New Yorker

Five days before the launch of Hunterbrook Media, one of its founders, Sam Koppelman, sat outside an East Village coffee shop and played me a voice mail. “We fucking took those cocksuckers down,” a man could be heard saying, articulating each profanity in a crisp staccato. “Fuck those guys. We’re No. 1.” The voice, Koppelman told me, belonged to Mat Ishbia, the C.E.O. of United Wholesale Mortgage and the majority owner of the Phoenix Suns. He was allegedly speaking about his closest industry rival, Rocket Mortgage. Hunterbrook was about to publish an investigation alleging that Ishbia’s company had aggressively pressured independent mortgage brokers to send business to U.W.M., potentially saddling home buyers with hundreds of millions of dollars more in closing costs. But what made this first foray into investigative journalism notable had already occurred: in advance of the story’s publication, Hunterbrook Media’s conjoined twin, Hunterbrook Capital, a hedge fund, had shorted U.W.M. stock and gone long on Rocket Mortgage.

Koppelman, who is Hunterbrook’s publisher, is twenty-eight, with large blue eyes and dark eyebrows. He has no professional banking or journalism experience, though he has worked as a political speechwriter and co-authored two books, one with the former acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal, the other with the former Attorney General Eric Holder. In the East Village, he wore a half-zip sweater and a white baseball cap emblazoned with “A Mouthful of Air,” the title of a novel by his mother, Amy, which was later adapted into a movie starring Amanda Seyfried. His father, Brian, is one of the showrunners of “Billions.”

Koppelman met his Hunterbrook co-founder, Nathaniel Horwitz, at the Harvard Crimson, where they once wrote an earnest op-ed about declining invitations to join Harvard’s exclusive final clubs. (“Should you join a group of predominantly white and privileged guys when you go to school with the most diverse and influential students in the world?”) After Harvard, Horwitz, who is twenty-eight and serves as Hunterbrook’s C.E.O., spent a few years with a Boston-based investment firm that specializes in biotech startups. His mother is the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Geraldine Brooks, and his father, Tony Horwitz, who died in 2019, was a best-selling author. “Hunterbrook” comes from Koppelman’s middle name, “Hunter”—as in Hunter S. Thompson—and honors Brooks.

“Nathaniel and Sam have a pretty ridiculous network,” Matthew Termine, one of the Hunterbrook reporters on the U.W.M. investigation, told me. E-mails that Koppelman wrote to the chair of Sony Entertainment about his application to Harvard appeared in the 2014 Sony Pictures leak, as did a note to the school on his behalf from Matt Damon. (Koppelman’s father co-wrote “Rounders” and “Ocean’s Thirteen.”) For a time, he dated the “Euphoria” star Maude Apatow. Horwitz, for his part, once wrote about a series of conversations he had with the Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes as her life and company crumbled. Hunterbrook’s advisers include Paul Steiger, the founder of ProPublica, and Daniel Okrent, the first public editor of the Times. Former Wall Street Journal editor-in-chief Matt Murray and the financial journalist Bethany McLean gave notes on the U.W.M. investigation before publication. Hunterbrook’s hedge fund has raised a hundred million dollars, and the company received seed funding from, among others, the venture arm of Laurene Powell Jobs’s Emerson Collective and the hedge-fund billionaire Marc Lasry, who, Brian Koppelman once told the Financial Times, helped the “Billions” showrunner develop an “understanding of the billionaire psyche.”

Termine, a lawyer by training, had attracted some notice for helping to uncover documents associated with a Brooklyn brownstone owned at the time by the 2016 Trump-campaign chairman Paul Manafort. Late last year, Termine was working at a mortgage-industry startup when the Financial Times ran a piece about Hunterbrook. He was familiar with an ultimatum that U.W.M. had publicly issued in 2021, stipulating that any brokers who did business with the company could not also work with its two closest competitors. “Over all, the idea was ‘All right, let’s see what the public records show about the impact of this ultimatum,’ ” Termine said. But his initial conversations with Koppelman were more broadly about how he might use public records to investigate stories. Because Hunterbrook operates under the S.E.C. rules that govern hedge funds, it relies on open-source journalism, meaning it can only seek out information that is already public. “My view was that real estate was a great area of potential focus for them,” Termine said. “Just because there’s so much public-record data out there.”

For the U.W.M. investigation, Hunterbrook cross-referenced two enormous data sets—one detailing individual mortgages, the other with information on the agents who brokered the loans—to show that, in many cases, mortgage brokers were funnelling business exclusively to U.W.M. The profanity-laced voice mail had emerged on Facebook and Reddit; Hunterbrook said it ran it through A.I.-detection software to help verify its authenticity. The investigation, which was published in early April, drew praise for its substantive look at U.W.M.’s business practices. “Monopolistic behavior is everywhere,” Matt Stoller, a liberal political commentator, posted on X. Hunterbrook boasted online that U.W.M. had removed videos from its Web site which Hunterbrook said contained misleading information about the mortgage-broker process. (A spokesperson for U.W.M. said that the videos were taken down for unrelated reasons.) Koppelman appeared on CNBC and the podcast of his close friend Pablo Torre, a sports reporter and ESPN commentator, to promote the story.

Central to Hunterbrook’s pitch is a promise to help solve a slice of journalism’s current business-model crisis. Investigations are notoriously expensive, and fewer and fewer outlets are able to sustain them. Koppelman told me, “The experiment we’re running is very specifically ‘Can you do investigations into companies that are committing wrongdoing, and can you break news in parts of the world that have been left behind by mainstream outlets—and do it profitably?’ ” But the way in which Hunterbrook aims to make money has raised its own set of concerns. “What’s different, maybe even messed up, about this model is you’re not primarily serving any particular audience that you want to develop a relationship with or that you feel needs the truth to be exposed,” Kelly McBride, who chairs the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership at the Poynter Institute, told me. “You’re primarily serving your investors in your hedge fund.”

U.W.M., in its response to Hunterbrook’s story, went further: “A hedge fund scheme using journalists to short a stock is not only unethical, it may be fraudulent.” (Hunterbrook indicated its investment positions in a note attached to the story.) A few days later, U.W.M. published a lengthy post, pointing to Termine’s previous work at the mortgage-industry startup, which it called “a Rocket Mortgage affiliated broker,” and to two recent federal-court cases challenging U.W.M.’s ultimatum that have so far been unsuccessful. (Termine refuted U.W.M.’s characterization of him, saying, “Sounds like, in U.W.M.’s telling, if a broker didn’t accept the ultimatum, they became a Rocket affiliate.”) U.W.M.’s stock, which had begun to dip a few days before the story’s publication—around the time that Hunterbrook secured its short position—fell, though not precipitously, and it has since made a slight recovery. Rocket Mortgage’s stock, meanwhile, which Hunterbrook had gone long on, fell as well.

In March, I met Hunterbrook’s general counsel, Fitzann Reid, at a coffee shop in Manhattan’s financial district. Reid, who wore a striped dress shirt and pink sweater, is a native New Yorker, though she now lives in Oakland. “I’m first-generation Jamaican,” she told me. “My parents moved here when I was a kid—they moved to Jamaica, Queens; I went to Jamaica High School. A lot of Jamaica going on.” She began her career in Hillary Clinton’s Senate office and, after law school, worked at the Securities and Exchange Commission. Before joining Hunterbrook, she was an in-house counsel for the activist hedge fund Engine No. 1; a partner at Engine No. 1’s outside law firm put her in touch with Koppelman and Horwitz. “I fully went into the conversation thinking, This idea is a grand one,” she said. “And then I met them, and we just had a really great conversation. So much of what they were talking about inspired me, and I’m a very mission-driven person.”

Hunterbrook employs three full-time “investigators,” two of whom have backgrounds not as journalists but as intelligence analysts. Murray, the former Wall Street Journal editor, runs a weekly editorial meeting. But it is Reid who lies at the heart of Hunterbrook’s business model. Under S.E.C. rules, many of the traditional tools of journalism—such as cultivating insider sources and conducting off-the-record interviews to learn non-public information—could constitute evidence of insider trading. At Hunterbrook, where reporting is being used to inform market trading, there is no seeking out of leakers or classified documents. The company prefers e-mails to phone calls, since the paper trail is easier to track. Screenshots of text messages must be posted in a Google Drive. Every detail in a story must be annotated with a source so that Reid can insure its provenance isn’t non-public information. Hunterbrook monitors the Slack messages and e-mails of its employees. “I still have lots of friends at the S.E.C.,” Reid told me. “So they’re well aware of this.”

Charges of insider trading are by no means unheard of in the world of journalism. In 1985, a Wall Street Journal columnist was convicted of participating in a scheme that made nearly seven hundred thousand dollars in trades that were based on his reporting; as recently as 2021, the indictment of a trader who pleaded guilty to securities fraud noted that some of his trades were made in coördination with stories that ran on Bloomberg News. If Reid determines that a story contains no compromising non-public information, Hunterbrook Media shares the reporting with Hunterbrook Capital, which, for now, has a single trader, an alum of Morgan Stanley. In the case of the U.W.M. investigation, the hedge-fund side of Hunterbrook was informed about the reporting nearly two weeks before publication. If the fund does well, journalists get a slice of the firm’s profits at the end of the year. “There are so many people and organizations that benefit from the work of good media, who are capturing a lot of financial value from it, except for the people in the organizations who are actually doing it,” Horwitz told me. “I think there’s an opportunity to reinvest that value in the people who are actually doing the work.”

Horwitz, who grew up in Virginia, Sydney, and on Martha’s Vineyard, is serious and intense, the sort of polished young professional who speaks in deliberate, paragraph-long arcs. “When I first met him, in college, he was, like, eighteen going on fifty,” Koppelman told me. “He was kind of fully baked.” Hunterbrook isn’t Koppelman and Horwitz’s first venture together. After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, in 2022, they launched Mayday Health, a nonprofit that disseminates information on how to obtain a medication abortion. “The way I’ve heard Sam describe it is that their dynamic is like ‘Barbie’-‘Oppenheimer,’ ” Liv Raisner, another Mayday founder and its executive director, said. “Sam wears Knicks jerseys on calls during the day, Nathaniel’s usually in a button-down.” Raisner lived with Koppelman and Horwitz in a Williamsburg apartment while they got Mayday off the ground. “It would not be atypical to wake up in our apartment and find Nathaniel on the couch having made slide decks for companies that didn’t exist,” Raisner said. “He would practice pitching on me.”

Horwitz, with deep-set blue eyes, sandy hair, and a wide, easy smile, is the spitting image of his father, who died unexpectedly at the age of sixty. “I obviously think about my dad every day, and he feels very present,” Horwitz told me. “I certainly often find myself asking, ‘How would he tackle this one?’ I rarely say that part out loud.” Early on, Horwitz ran the idea for Hunterbrook by his mother, Geraldine Brooks, who, early in her career, worked as a foreign correspondent at the Wall Street Journal. Her reaction, Horwitz said, was “This is a good idea. It’s a bit crazy.” She gave him a list of people to speak with, including Steiger, her former boss at the Wall Street Journal; her Columbia Journalism School classmate William Cohan, who has a byline on the U.W.M. investigation; and Okrent. “I put them through every possible hoop involving the ethics of it,” Okrent told me. “They had anticipated ninety-nine out of a hundred and had answers.”

Koppelman’s first post announcing Hunterbrook read, “Hunterbrook is founded on a crazy premise: Great reporting doesn’t have to be a bad business.” But, when we met in the East Village, he said, “I don’t consider this journalism.” Horwitz told me that Hunterbrook’s work “achieves the same goals of journalism” and “fills gaps that have widened as traditional journalism has become harder and harder to sustain.” A lawyer couldn’t have threaded the needle better. The pair have also cleverly positioned Hunterbrook as a virtuous experiment that might fail. “We’re pretty up-front about that,” Koppelman said. “For a ten-million-dollar newsroom budget, a lot of people may have hired a lot more people at this point, and we’re not doing that because we don’t want to have the classic media-company thing of a hundred hires one year, a hundred fires the next.”

Unlike traditional media, Hunterbrook isn’t trying to make money by growing its audience—it has no paywall—but a dedicated readership could help identify potential investigations. Bellingcat, the open-source investigative-journalism group, which is known for reporting on wars and international espionage via the public domain, operates a newsroom of about forty full-time staff on an annual budget of four million euros. But its founder, Eliot Higgins, told me that an undervalued component of its success is its dedicated audience. “It’s not so much that we have a lot of staff,” he said. “It’s that we have a big community network. We have our own Discord server with twenty-eight thousand members, and they’re always digging through stuff and finding potential story leads that we’ll publish on the Web site.” Higgins added, “You can do the best investigation in the world—if you don’t have a network to communicate that to, then you’re not going to get very far with it.”

In many ways, Hunterbrook behaves more like a hedge fund than a journalism outlet. A core principle of traditional journalism, of course, is that reporters should pursue information if it is in the public good—not for remunerative reasons. Conflict disclosure is another basic tenet of journalism, but Hunterbrook doesn’t disclose the investors in its hedge fund. (Koppelman said that the company has emphasized its editorial independence to investors: “They understand those are the table stakes.”) The parts of the world that Hunterbrook seems to think have been left behind by the media, some of the places where it has hired freelance correspondents—Mongolia, Peru, Namibia, Brazil—are conveniently rich in natural resources.

The Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine, who has written about Hunterbrook in his newsletter, told me that the outlet, at least in its early stages, reminded him of Hindenburg Research, a short-selling firm that investigates companies, then publishes its findings in the hope of moving the market in a direction that benefits its financial positions. But one interesting Hunterbrook innovation, Levine noted, was its salary arbitrage. “Think about how a hedge fund works: you have an office in New York with fifteen people you pay a million dollars a year, and their job is to find out interesting things that have financial implications around the world,” he said. “Whereas you hire a local journalist, you pay them effectively nothing—and they probably have better information.”

Horwitz insisted that Hunterbrook is not a short-selling firm, not least because it sometimes goes long. The organization also publishes stories even if it’s not making trades on them and, Horwitz added, its investigators reach out to the targets of their investigations “in good faith” before publication. But Horwitz was slightly evasive when I asked what Hunterbrook pays its journalists. No one was making less than a hundred thousand dollars as a base salary, he said. “The upper limit is potentially incredibly high because it’s based on the performance of an investment fund, which is not an upside opportunity that reporters have had access to.” Another side market for Hunterbrook employees, he went on, is filing whistle-blower reports with the S.E.C. (Termine and a second, unnamed reporter on the U.W.M. story have filed one such report.) If the S.E.C. fine on a company is greater than a million dollars, whistle-blowers can collect ten-to-thirty per cent of the money. But there are also punitive consequences if a Hunterbrook journalist gets something wrong in a story: they could be sued for securities fraud. Errors in an article, Horwitz told me, “can trigger a clawback of a bonus.”

On April 5th, the front page of the Detroit News featured a story about a class-action suit filed against U.W.M. for racketeering. It sought to hold the company “accountable for orchestrating and executing a deliberate scheme, in coordination with a host of corrupted mortgage brokers, to cheat hundreds of thousands of borrowers out of billions of dollars in excess fees and costs that they paid to finance their homes.” In a decidedly unusual arrangement prior to publication, Hunterbrook shared its findings not only with state attorneys general but with the law firm Boies Schiller Flexner L.L.P., which filed the suit. The Hunterbrook Foundation, an affiliated nonprofit, had “entered an agreement with the law firm,” according to Hunterbrook’s Web site, and “proceeds the Hunterbrook Foundation receives from such litigation would be used to fund local news.”

Of course, local news is where journalism faces its biggest business crisis. “Great investigative journalism often does good; it often exposes things and changes the power balance,” McBride, of the Poynter Institute, said. “But I don’t know that it will solve the problem that we have—which is there’s not enough local journalism, which makes people distrust the entire system.” Koppelman and Horwitz have assembled a pedigreed team. They claim to be pursuing investigations in the public interest. (What could be more relevant to the American public, Horwitz asked me, than news about possible pervasive mortgage fraud?) But they also are hoping that their new enterprise will make them rich. The more cynical take is that Hunterbrook has co-opted the mission-driven language of journalism when, in fact, it is simply a hedge fund that hires journalists, as many hedge funds already do. Or, perhaps, as Okrent told me, journalists should stop being so precious about tradition. Many of the people criticizing Hunterbrook are likely also despairing about the state of the industry. “So how are we going to save it?” Okrent said. “What are we going to do so we can still do journalism?”

For now, Hunterbrook’s biggest challenge is one familiar to most newsrooms: finding enough stories to sustain its business model. But in its case there is arguably an even higher degree of difficulty. To be profitable, Hunterbrook needs stories that are both open-source and powerful enough to move markets. “My biggest concern is that we do really exceptional work, we open-source a lot of valuable information, but that we’re not able to do that sustainably for years,” Horwitz said. In a few recent investigations—including stories about companies doing business with Myanmar’s junta—Hunterbrook did not trade on their information, presumably because the reporting either contained non-public disclosures or couldn’t be leveraged for a return on the market. “I’m not asking people to trust this new model,” Horwitz told me. “It needs to prove itself.” ♦

Media

Trump could cash out his DJT stock within weeks. Here’s what happens if he sells

Former President Donald Trump is on the brink of a significant financial decision that could have far-reaching implications for both his personal wealth and the future of his fledgling social media company, Trump Media & Technology Group (TMTG). As the lockup period on his shares in TMTG, which owns Truth Social, nears its end, Trump could soon be free to sell his substantial stake in the company. However, the potential payday, which makes up a large portion of his net worth, comes with considerable risks for Trump and his supporters.

Trump’s stake in TMTG comprises nearly 59% of the company, amounting to 114,750,000 shares. As of now, this holding is valued at approximately $2.6 billion. These shares are currently under a lockup agreement, a common feature of initial public offerings (IPOs), designed to prevent company insiders from immediately selling their shares and potentially destabilizing the stock. The lockup, which began after TMTG’s merger with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), is set to expire on September 25, though it could end earlier if certain conditions are met.

Should Trump decide to sell his shares after the lockup expires, the market could respond in unpredictable ways. The sale of a substantial number of shares by a major stakeholder like Trump could flood the market, potentially driving down the stock price. Daniel Bradley, a finance professor at the University of South Florida, suggests that the market might react negatively to such a large sale, particularly if there aren’t enough buyers to absorb the supply. This could lead to a sharp decline in the stock’s value, impacting both Trump’s personal wealth and the company’s market standing.

Moreover, Trump’s involvement in Truth Social has been a key driver of investor interest. The platform, marketed as a free speech alternative to mainstream social media, has attracted a loyal user base largely due to Trump’s presence. If Trump were to sell his stake, it might signal a lack of confidence in the company, potentially shaking investor confidence and further depressing the stock price.

Trump’s decision is also influenced by his ongoing legal battles, which have already cost him over $100 million in legal fees. Selling his shares could provide a significant financial boost, helping him cover these mounting expenses. However, this move could also have political ramifications, especially as he continues his bid for the Republican nomination in the 2024 presidential race.

Trump Media’s success is closely tied to Trump’s political fortunes. The company’s stock has shown volatility in response to developments in the presidential race, with Trump’s chances of winning having a direct impact on the stock’s value. If Trump sells his stake, it could be interpreted as a lack of confidence in his own political future, potentially undermining both his campaign and the company’s prospects.

Truth Social, the flagship product of TMTG, has faced challenges in generating traffic and advertising revenue, especially compared to established social media giants like X (formerly Twitter) and Facebook. Despite this, the company’s valuation has remained high, fueled by investor speculation on Trump’s political future. If Trump remains in the race and manages to secure the presidency, the value of his shares could increase. Conversely, any missteps on the campaign trail could have the opposite effect, further destabilizing the stock.

As the lockup period comes to an end, Trump faces a critical decision that could shape the future of both his personal finances and Truth Social. Whether he chooses to hold onto his shares or cash out, the outcome will likely have significant consequences for the company, its investors, and Trump’s political aspirations.

Media

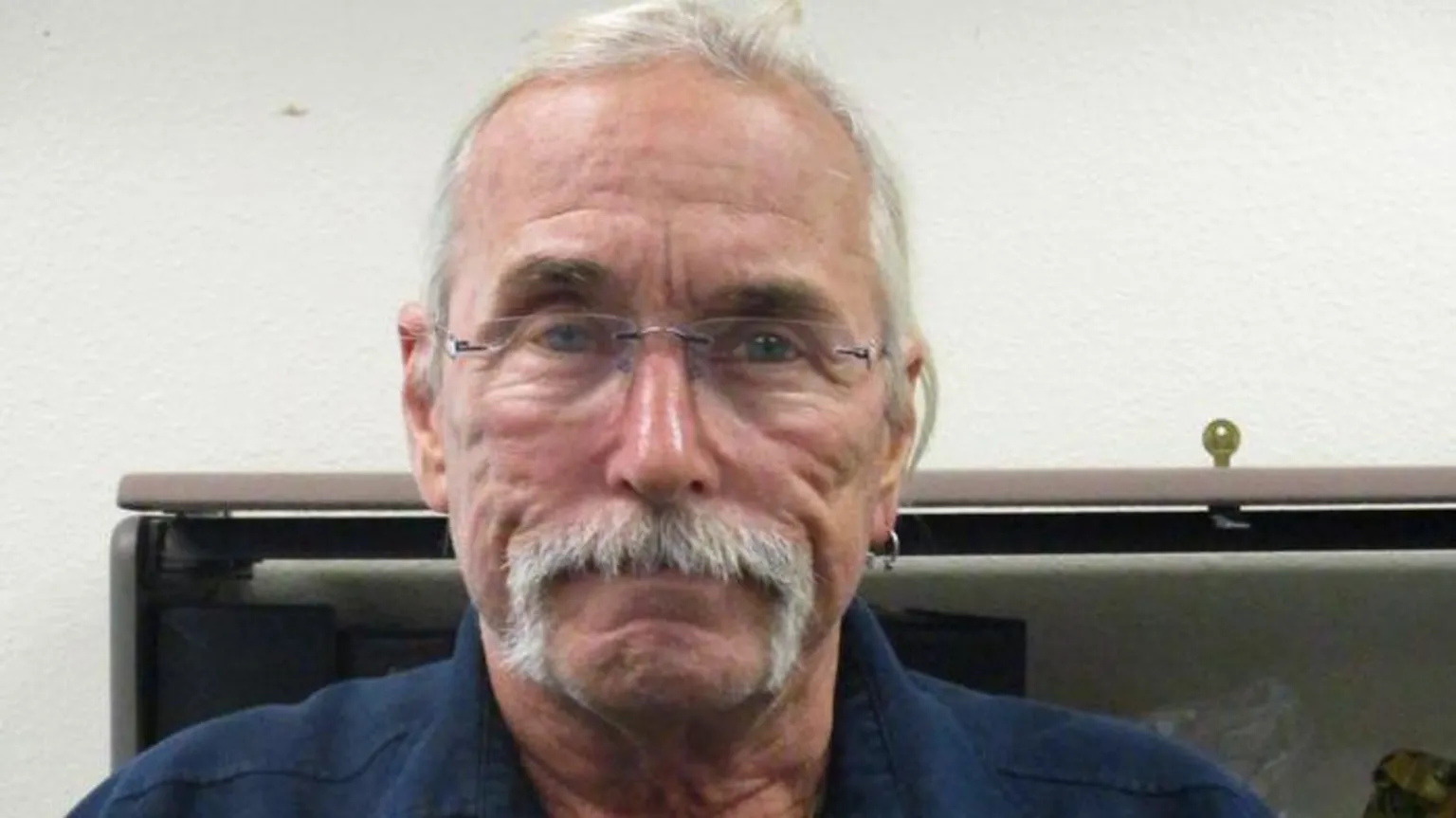

Arizona man accused of social media threats to Trump is arrested

Cochise County, AZ — Law enforcement officials in Arizona have apprehended Ronald Lee Syvrud, a 66-year-old resident of Cochise County, after a manhunt was launched following alleged death threats he made against former President Donald Trump. The threats reportedly surfaced in social media posts over the past two weeks, as Trump visited the US-Mexico border in Cochise County on Thursday.

Syvrud, who hails from Benson, Arizona, located about 50 miles southeast of Tucson, was captured by the Cochise County Sheriff’s Office on Thursday afternoon. The Sheriff’s Office confirmed his arrest, stating, “This subject has been taken into custody without incident.”

In addition to the alleged threats against Trump, Syvrud is wanted for multiple offences, including failure to register as a sex offender. He also faces several warrants in both Wisconsin and Arizona, including charges for driving under the influence and a felony hit-and-run.

The timing of the arrest coincided with Trump’s visit to Cochise County, where he toured the US-Mexico border. During his visit, Trump addressed the ongoing border issues and criticized his political rival, Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris, for what he described as lax immigration policies. When asked by reporters about the ongoing manhunt for Syvrud, Trump responded, “No, I have not heard that, but I am not that surprised and the reason is because I want to do things that are very bad for the bad guys.”

This incident marks the latest in a series of threats against political figures during the current election cycle. Just earlier this month, a 66-year-old Virginia man was arrested on suspicion of making death threats against Vice President Kamala Harris and other public officials.

Media

Trump Media & Technology Group Faces Declining Stock Amid Financial Struggles and Increased Competition

Trump Media & Technology Group’s stock has taken a significant hit, dropping more than 11% this week following a disappointing earnings report and the return of former U.S. President Donald Trump to the rival social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter. This decline is part of a broader downward trend for the parent company of Truth Social, with the stock plummeting nearly 43% since mid-July. Despite the sharp decline, some investors remain unfazed, expressing continued optimism for the company’s financial future or standing by their investment as a show of political support for Trump.

One such investor, Todd Schlanger, an interior designer from West Palm Beach, explained his commitment to the stock, stating, “I’m a Republican, so I supported him. When I found out about the stock, I got involved because I support the company and believe in free speech.” Schlanger, who owns around 1,000 shares, is a regular user of Truth Social and is excited about the company’s future, particularly its plans to expand its streaming services. He believes Truth Social has the potential to be as strong as Facebook or X, despite the stock’s recent struggles.

However, Truth Social’s stock performance is deeply tied to Trump’s political influence and the company’s ability to generate sustainable revenue, which has proven challenging. An earnings report released last Friday showed the company lost over $16 million in the three-month period ending in June. Revenue dropped by 30%, down to approximately $836,000 compared to $1.2 million during the same period last year.

In response to the earnings report, Truth Social CEO Devin Nunes emphasized the company’s strong cash position, highlighting $344 million in cash reserves and no debt. He also reiterated the company’s commitment to free speech, stating, “From the beginning, it was our intention to make Truth Social an impenetrable beachhead of free speech, and by taking extraordinary steps to minimize our reliance on Big Tech, that is exactly what we are doing.”

Despite these assurances, investors reacted negatively to the quarterly report, leading to a steep drop in stock price. The situation was further complicated by Trump’s return to X, where he posted for the first time in a year. Trump’s exclusivity agreement with Trump Media & Technology Group mandates that he posts personal content first on Truth Social. However, he is allowed to make politically related posts on other social media platforms, which he did earlier this week, potentially drawing users away from Truth Social.

For investors like Teri Lynn Roberson, who purchased shares near the company’s peak after it went public in March, the decline in stock value has been disheartening. However, Roberson remains unbothered by the poor performance, saying her investment was more about supporting Trump than making money. “I’m way at a loss, but I am OK with that. I am just watching it for fun,” Roberson said, adding that she sees Trump’s return to X as a positive move that could expand his reach beyond Truth Social’s “echo chamber.”

The stock’s performance holds significant financial implications for Trump himself, as he owns a 65% stake in Trump Media & Technology Group. According to Fortune, this stake represents a substantial portion of his net worth, which could be vulnerable if the company continues to struggle financially.

Analysts have described Truth Social as a “meme stock,” similar to companies like GameStop and AMC that saw their stock prices driven by ideological investments rather than business fundamentals. Tyler Richey, an analyst at Sevens Report Research, noted that the stock has ebbed and flowed based on sentiment toward Trump. He pointed out that the recent decline coincided with the rise of U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris as the Democratic presidential nominee, which may have dampened perceptions of Trump’s 2024 election prospects.

Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida, offered a grim long-term outlook for Truth Social, suggesting that the stock would likely remain volatile, but with an overall downward trend. “What’s lacking for the true believer in the company story is, ‘OK, where is the business strategy that will be generating revenue?'” Ritter said, highlighting the company’s struggle to produce a sustainable business model.

Still, for some investors, like Michael Rogers, a masonry company owner in North Carolina, their support for Trump Media & Technology Group is unwavering. Rogers, who owns over 10,000 shares, said he invested in the company both as a show of support for Trump and because of his belief in the company’s financial future. Despite concerns about the company’s revenue challenges, Rogers expressed confidence in the business, stating, “I’m in it for the long haul.”

Not all investors are as confident. Mitchell Standley, who made a significant return on his investment earlier this year by capitalizing on the hype surrounding Trump Media’s planned merger with Digital World Acquisition Corporation, has since moved on. “It was basically just a pump and dump,” Standley told ABC News. “I knew that once they merged, all of his supporters were going to dump a bunch of money into it and buy it up.” Now, Standley is staying away from the company, citing the lack of business fundamentals as the reason for his exit.

Truth Social’s future remains uncertain as it continues to struggle with financial losses and faces stiff competition from established social media platforms. While its user base and investor sentiment are bolstered by Trump’s political following, the company’s long-term viability will depend on its ability to create a sustainable revenue stream and maintain relevance in a crowded digital landscape.

As the company seeks to stabilize, the question remains whether its appeal to Trump’s supporters can translate into financial success or whether it will remain a volatile stock driven more by ideology than business fundamentals.

-

News8 hours ago

News8 hours agoB.C. to scrap consumer carbon tax if federal government drops legal requirement: Eby

-

News7 hours ago

News7 hours agoA linebacker at West Virginia State is fatally shot on the eve of a game against his old school

-

Sports9 hours ago

Sports9 hours agoLawyer says Chinese doping case handled ‘reasonably’ but calls WADA’s lack of action “curious”

-

News18 hours ago

News18 hours agoReggie Bush was at his LA-area home when 3 male suspects attempted to break in

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoRCMP say 3 dead, suspects at large in targeted attack at home in Lloydminster, Sask.

-

Sports3 hours ago

Sports3 hours agoCanada’s Marina Stakusic advances to quarterfinals at Guadalajara Open

-

News7 hours ago

News7 hours agoHall of Famer Joe Schmidt, who helped Detroit Lions win 2 NFL titles, dies at 92

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoBad weather and boat modifications led to capsizing off Haida Gwaii, TSB says