Art

X-ray visions, stately sculptures and swelling seas – the week in art – The Guardian

Exhibition of the week

Tony Cragg

Wobbly cosmic abstract forms materialise around one of Britain’s most spectacular stately homes.

Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, until 22 September

Also showing

Emma Stibbon: Melting Ice | Rising Tides

A personal project to observe the climate crisis, from the Arctic to British coasts, in drawing and photography.

Towner Eastbourne, 9 May-15 September

Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King

Art, weapons and armour bring to life Ranjit Singh, “Lion of the Punjab”, who established the Sikh empire in the early 1800s.

Wallace Collection, London, until 20 October

Paul Maheke: To Be Blindly Hopeful

Immersive installation that includes X-ray like spectral images of selfhood.

Mostyn, Llandudno, until 29 June

Simon Starling

Houseboat for Ho is Starling’s design for housing in a Danish community threatened with inundation by the sea.

Modern Institute, Glasgow, until 25 May

Image of the week

Look familiar? You may recognise Yan Wang Preston’s delightfully subversive He from Manet’s Olympia. The UK-based Chinese photographer’s reworkings of famous artists’ works are clever, concise reversals that reveal the original’s assumptions and exclusions: rewriting art history, one liberated pair of buttocks at a time.

What we learned

The UK’s National Crime Agency is selling a Frank Auerbach painting for seven figures

Liberty shines brighter in France, after Delacroix’s iconic painting is restored

Miami is driving a craze for car-chitecture

Still life is more subversive than you think

Dean Sameshima celebrates the art of the sexual outlaw

Diana Matar’s latest photography series documents US deaths at the hands of police

Iranian artist – and Paralympian – Mohammad Barrangi explores disability and migration

Old pianos become art works in Bath

Grim relics of Hamas’s 7 October attack on Israel have gone on show in New York

Britain’s museum of the year contenders were announced

Colonial imagery at the RIBA’s headquarters has been challenged by global artists

Masterpiece of the week

The Virgin and Child by Masaccio, 1426

This painting does not immediately look revolutionary to modern eyes. Yet when it was done 600 years ago it was challenging not only artistic traditions but human cognition itself. Look at the Virgin Mary’s throne and you can see it is pictured in deep, realistic perspective. This illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat painted panel was a scientific wonder in the early 1400s. Masaccio reveals the solidity and roundedness of physical existence with a precision artists before him had barely attempted. Once you see the perspective of the throne you can also see how full and lifelike the faces are. Yet it is a stern, severe work. Masaccio has a moral edge. Why does the Virgin’s throne resemble an ancient Roman building? When this was painted, Masaccio’s city state Florence was gripped by the ideal of reviving the civic virtue of the Roman republic. This masterpiece is not just religious but political.

National Gallery, London

Don’t forget

To follow us on X (Twitter): @GdnArtandDesign.

Sign up to the Art Weekly newsletter

If you don’t already receive our regular roundup of art and design news via email, please sign up here.

Get in Touch

If you have any questions or comments about any of our newsletters please email newsletters@theguardian.com

Art

Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

- Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York BBC.com

- A duct-taped banana sells for $6.2 million at an art auction NPR

- Is this banana duct-taped to a wall really worth $6.2 million US? Somebody thought so CBC.ca

Art

40 Random Bits of Trivia About Artists and the Artsy Art That They Articulate – Cracked.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

40 Random Bits of Trivia About Artists and the Artsy Art That They Articulate Cracked.com

Source link

Art

John Little, whose paintings showed the raw side of Montreal, dies at 96 – CBC.ca

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

John Little, whose paintings showed the raw side of Montreal, dies at 96 CBC.ca

Source link

-

News17 hours ago

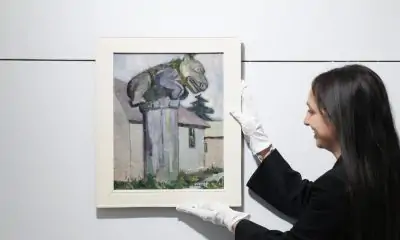

News17 hours agoEstate sale Emily Carr painting bought for US$50 nets C$290,000 at Toronto auction

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoCanada’s Hadwin enters RSM Classic to try new swing before end of PGA Tour season

-

News18 hours ago

News18 hours agoAll premiers aligned on push for Canada to have bilateral trade deal with U.S.: Ford

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoClass action lawsuit on AI-related discrimination reaches final settlement

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoTrump nominates former congressman Pete Hoekstra as ambassador to Canada

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoFormer PM Stephen Harper appointed to oversee Alberta’s $160B AIMCo fund manager

-

News17 hours ago

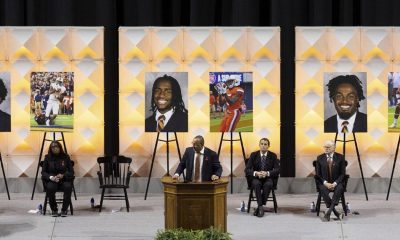

News17 hours agoEx-student pleads guilty to fatally shooting 3 University of Virginia football players in 2022

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoComcast to spin off cable networks that were once the entertainment giant’s star performers