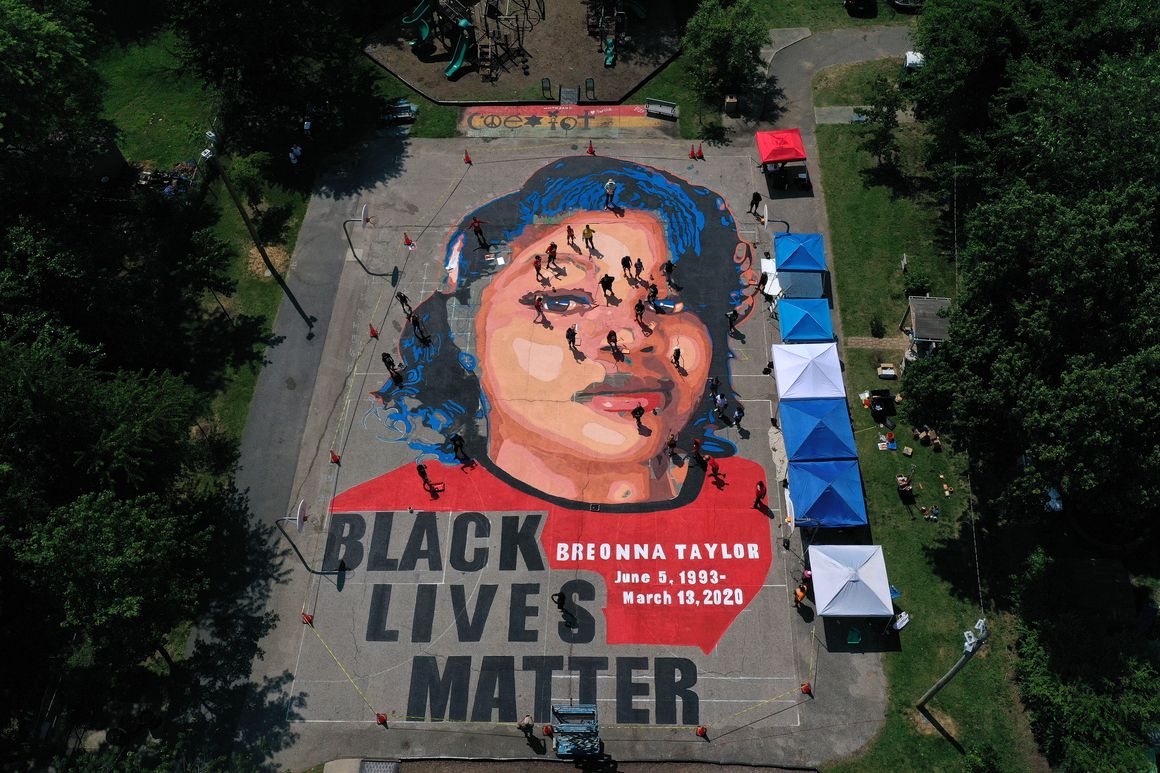

Patrick Smith/Getty Images

By TERESA WILTZ

09/28/2020 04:30 AM EDT

Teresa Wiltz is a politics editor at POLITICO.

.cms-textAlign-lefttext-align:left;.cms-textAlign-centertext-align:center;.cms-textAlign-righttext-align:right;.cms-magazineStyles-smallCapsfont-variant:small-caps;

Every Black family has a trauma story, even the most privileged, a story of a great-grandfather swinging from a tree, of cousins fleeing North in the middle of the night, of a sister or a brother or a husband who came this close to disaster with a cop.

These stories are extraordinary, because trauma always feels outsized. But they’re ordinary, too—ordinary in their commonplace-ness, a shared pain that’s tucked away, not talked about, because to do so picks at the scabs of barely healed wounds.

But for some Black families, trauma becomes a very public thing. They’re shoved into the spotlight, against their will, as their loved ones, ordinary Black folks, become extraordinary. Icons. Martyrs. Frozen in murals, fossilized on magazine covers, their personal lives dissected in the media. For them, grief becomes performance.

On Friday, this was Breonna Taylor’s family. Months after Taylor was killed by Louisville police officers executing a misfired warrant in the middle of the night, and two days after a Kentucky grand jury declined to charge police officers in her death, her family and friends stood in a downtown park. Amid a makeshift memorial to Taylor, an EMT technician who had hoped to buy her own home, they held hands, wearing masks that read, “Breonna Taylor.”

Perhaps the grief, perhaps the public-ness of it all was too much for Tamika Palmer, Taylor’s mom. She didn’t say a word, standing there in, in tears. Her own mask read “Black Queen,” a reference to what she fondly calls her daughter. Instead, Palmer asked Taylor’s aunt, Bianca Austin, to read what she’d written about her sadness—and her rage.

“When I speak on it, I’m considered an angry Black woman,” Austin read. “But know this, I am an angry Black woman. … but angry because our Black women keep dying at the hands of police officers … You can take the dog out of the fight. But you can’t take the fight out of the dog.”

Taylor’s family has joined what the father of Jacob Blake, another 2020 shooting victim, describes as a “fraternity” all too familiar now in American life: the families of Black Americans killed at the hands of police, or by self-deputized vigilantes.

That would be the families of Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark, Michelle Cusseaux, Jordan Davis, George Floyd, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Daniel Prude, Botham Jean, Atatiana Jefferson, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Aura Rosser, Alton Sterling…. In seeking justice, they become reluctant activists, forced to become instant experts in public relations and advocacy—and also becoming part of a long history in which Black trauma has become inextricably entangled with political movements.

“There’s a long history of unjust killing of African Americans that thrusts family members into an almost impossible situation,” said Omar Wasow, a political-science professor at Princeton University, who studies protest movements.

And in that history, there is kinship. Martin Luther King Jr., the greatest icon of the civil rights movement, was assassinated by a white man who’d decided King had gone too far, leaving behind a family whose activism, and lives, are shadowed by trauma to this day. On the day Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron announced the grand jury’s decision, Bernice King, his youngest daughter, acknowledged the Taylors had just joined that legacy. “Praying for Breonna’s mother and family,” she tweeted, “Because they knew and loved her before her name became a hashtag.”

To be sure, tragedy has driven other families into the public eye as well. The parents of children killed in the Sandy Hook massacre, or the Parkland shooting, also had to deal with grief while under the klieg lights of instant, unwanted fame. But families like Taylor’s have yet another burden to carry in post-apartheid America: They’re expected to hold up a race, to counter the character assassinations of their loved ones by media looking to exonerate the police, to plead for peace in the wake of protests. All at the same time they’re grieving.

“These victims’ families are called upon to seek justice and call for peace in the same ragged moment,” said Cornell Brooks, the former president of the NAACP, who worked on behalf of the families of police shooting victims Michael Brown, Philando Castile and Jamar Clark.

Says Brooks, now a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School: “It’s regular, routine and obscene.”

The Kentucky grand jury decision came down on the 65th anniversary of the acquittal of the white murderers of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Chicago boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman. His mother, Mamie, famously insisted on an open casket at her son’s funeral, using her tragedy to help launch the civil rights movement.

Mamie Till and other civil rights activists like the U.S. Congressman John Lewis used the model of “redemptive suffering” as a way to dramatize injustice. “No parent would ever choose this,” Wasow said. “But she was very intentional about how to transform her suffering into something that might serve a greater good.”

Today, social media and the ubiquity of smartphones with cameras means these moments of state violence are documented, making it easier to dramatize the injustice without having to open a casket for the world to see.

Some family members go further, and harness their suffering—and fury—to launch political careers. Lucy McBath, the mother of Jordan Davis, the Georgia teen killed by a white man for playing loud music in a parking lot, channeled her grief into gun-control activism. She’s now a Democrat serving in the U.S. Congress. In August, Trayvon Martin’s mother, Sybrina Fulton, narrowly lost a race for a seat on the Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners.

On Thursday, Fulton tweeted, “#BreonnaTaylor could have been You, your daughter, your sister, your cousin or your friend @home sleeping comfortably in her own bed, let that marinate.”

But for many families, the trauma of losing a family member so publicly, while an iPhone bears witness, takes both a physical and emotional toll—harder, perhaps, because it was a fight they never sought. Martin Luther King Jr. was groomed for the spotlight from a young age. But his kids weren’t. Malcolm X, the son of a man murdered for his fiery sermons, knew the risks: “I live like a man who is dead already.” But his kids didn’t, and his grandson, also named Malcolm, didn’t either.

The weight of the loss, and the stresses that follow, is a whole second arc of tragedy in the Black political story. Malcolm X’s daughter, Qubilah Shabazz, who was 4 when she saw her father murdered, was charged with hiring a hitman to kill Louis Farrakhan, whom she believed was responsible for his death. (The charges were later dropped.) Her son, Malcolm, was 12 when he started a fire that killed his grandmother, Betty Shabazz. And he was 28 when he was found beaten to death in Mexico City in 2013.

What does inherited trauma do to the mind, to the body, to the soul? The daughter of Eric Garner, the Staten Island man killed by police in a chokehold, became an activist in the wake of his death, only to die of a heart attack at age 27 in 2016.

Some seek solace in the notion that the death of their loved ones meant… something. George Floyd’s daughter, at a protest this year, sat on the shoulders of a family friend, beaming as she declared, “Daddy changed the world.”

Daddy might be changing the world, but he won’t be tucking her in at night anymore.

My own family told its trauma stories, too. Like that time when my maternal grandfather, a doctor in Jim Crow Atlanta, was heading home after a long night at the hospital. Tired. And there, waiting for him, was a white cop who liked to mess with him. Just because. Because he could. Every time my grandfather would drive around the bend in the road, heading home, the cop would be there, lying in wait. He’d pull the Black doctor over, because he could.

Until one night my grandfather, a very proper Southern gentleman, decided he couldn’t anymore. So Granddaddy got out of the car and administered a righteous beat-down to that racist cop.

He was lucky. The cop didn’t kill him. He just hauled him off to jail, where he spent the night, before a sympathetic judge, hearing his story, let him go. The privilege of his job and his standing shielded him, to be sure. To a point.

When I was a grad student, the office manager at my school, Akua Njeri, was the widow of Fred Hampton, a brilliant and charismatic Black Panther leader. Hampton, the head of the Illinois Black Panther Party, was 21 when he was gunned down by Chicago police officers as he lay in bed, with a very pregnant Njeri by his side. Their son, Fred Jr., was born just weeks after his father’s execution.

And as a student activist at the University of Michigan in the late ’80s, my husband was beaten by police officers at protests on more than one occasion. A colleague recalls the time an undercover police officer held a gun to her husband’s head in a case of mistaken identity. You already know why. He “matched the description”: Black male with an Afro and a denim jacket—which, she said, described virtually every young Black man in the late ’70s.

At the press conference for Breonna Taylor’s family, their attorney, Benjamin Crump, roll-called the names of those who reached out to Taylor’s family in sad solidarity: Sandra Bland’s family. Trayvon Martin’s family. Michael Brown’s family. Botham Jean’s mother. George Floyd’s family.

Jacob Blake Sr., whose son, Jacob Jr., was shot multiple times in the back in August by a Kenosha, Wisc., police officer, partially paralyzing him, told the crowd he drove eight hours in a show of support for Taylor’s kin. “I knew I had to be here, standing next to my fraternity,” Blake said. “We didn’t choose this fraternity. This fraternity chose us.

“I knew this family needed some energy and I said, ‘I’m coming. I’m coming.’ Because we’re not going to lay down anymore. You can’t stop the revolution.”