There was one place, though, that her mother dreaded visiting: the Deep South.

Her mother saw it as a forbidding land of lynch mobs and “Whites Only” signs, where Black people went missing just for trying to vote. Burton’s mother grew up in segregated Virginia and was so mistrustful of the South she once dissuaded her daughter from vacationing in Atlanta and encouraged her to visit the Bahamas instead.

“My mother sent me out of the country before she sent me to the Deep South,” Burton says.

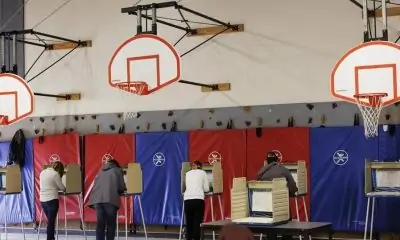

Burton, who is 48, just got a little payback. After moving to Atlanta from Maryland six years ago, she became part of a crucial bloc of Black voters who helped Democrats seize control of the US Senate. They mobilized in record numbers to elect the Rev. Raphael Warnock, a Black man from Savannah, and Jon Ossoff, a Jewish man from Atlanta.

Burton thought of all the Black people like her who migrated from elsewhere to Georgia to reclaim political power that was taken away from their parents and grandparents, who fled the Jim Crow South in fear.

“It’s poetic justice,” says Burton, a cultural critic and founder of

The Burton Wire, which produces stories on race, class, and gender. “The descendants of the people who were pushed out of the South, who had no power, who knew they could go missing if they tried to vote, have returned and they’re making it work for them. It’s been a long time coming.”

The stunning election results in Georgia have rightly been attributed to the relentless work of voting-rights organizers such as Stacey Abrams, the former gubernatorial candidate whose group,

Fair Fight, is

credited with registering 800,000 new voters in Georgia.

But those victories also happened because of a series of personal decisions made years ago by little-known transplants like Burton. They are part of what’s called “

The New Great Migration,” and without them, Warnock and Ossoff wouldn’t have stood a chance.

The unsung Black transplants changing the South

More than

a million Black people have moved to Georgia and other Southern states in the last 30 years. Many have started to flex political powers that were denied to their ancestors. They’re not just winning local races for mayor and city council, they’re shaping national politics.

What happened in Georgia this week is a culmination of this trend. Some trace the shift to President Obama’s successful 2008 presidential run, when he won Virginia and North Carolina. Others cite a multiracial progressive movement called Moral Mondays that turned North Carolina from a red state into a political battleground.

The Rev. William Barber II, an activist and author, is credited with helping transform North Carolina into a place where the GOP cannot take victory for granted. The state now has a Democratic governor.

Barber, 57, says the Democratic victories in Georgia can spread throughout the South if candidates are not afraid to run on an unabashedly progressive platform, as Warnock and Ossoff did, that champions the working class.

“Georgia doesn’t have to be an anomaly,” says Barber, whose parents moved to North Carolina from Indiana. “Georgia literally shows what’s possible when you put messaging, mobilization, and the investment of money in there.”

He points out, though, that the newfound Black political clout in Georgia is not unprecedented. It’s a return to what he calls “fusion politics” — a late 19th-century movement that saw Blacks and progressive Whites change politics throughout the South.

Much of this progress occurred during Reconstruction, that period when Black and White voters in the South sent two Black senators to the US Senate and elected more than 2,000 Black congressmen, judges, sheriffs and tax collectors.

“A superficial political analysis will say that the Black vote elected Warnock and Ossoff, but a serious political analysis will say that Black, White and Latino voters elected them,” Barber says.

Atlanta is key to the New Great Migration

Any serious political analysis of the Democrats’ victories in Georgia must also examine Atlanta’s mythical hold on Black America. The New Great Migration gave Ossoff and Warnock a more level playing field, because Atlanta has long been a top destination for Black transplants from around the country.

In the 1970s, Ebony and Jet magazines promoted Atlanta as the “Black Mecca” of the South because of its vibrant middle class, renowned Black colleges like Morehouse and Spelman, and its string of popular Black mayors like Maynard Jackson and Andrew Young. It’s also been called the “cradle of the civil rights movement” as the birthplace of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who used the city as a home base to change the nation.

Voters in Atlanta and its predominantly Black suburbs were

crucial to Warnock and Ossoff’s victories, and many of these voters came from elsewhere. In 2019, 43% of eligible Black voters in Georgia were born outside of the state, according to the

Pew Research Center. In the Atlanta metro area, 76% of eligible Black voters were born outside of Georgia.

Many of these Black transplants came because they didn’t have the same fear of the South as their parents. They got active in politics and civic affairs and become what Burton calls “supervoters”: people who vote in local, state and national elections.

“If there’s an election for a dog catcher, supervoters are going to vote in it,” Burton says.

They’re people like Charles M. Blow, the New York Times columnist, who moved to Atlanta from New York City a year ago.

“I chose Atlanta because many of my friends were already there, having moved to the ‘hot’ Southern city after college, and because I saw Georgia as on the cusp of transformational change,” Blow

wrote in a recent column. “I say to Black people: Return to the South, cast down your anchor and create an environment in which racial oppression has no place.”

But across the South, Black political power outside of Georgia is still uneven. Black voters in South Carolina helped send Biden to the White House when they threw their support behind his then-floundering campaign during the Democratic primaries. But they have not changed the White Republican dominance of their state.

Mississippi is a textbook example of why a large Black populace doesn’t necessarily translate into political power. It has the highest percentage of Black people in any state — about 38% — but they are virtually locked out the state’s political power. It doesn’t have Georgia’s booming economy or its influx of multiracial, college-educated transplants who tend to be progressive voters. White Republicans have dominated state politics in Mississippi since the late 19th century.

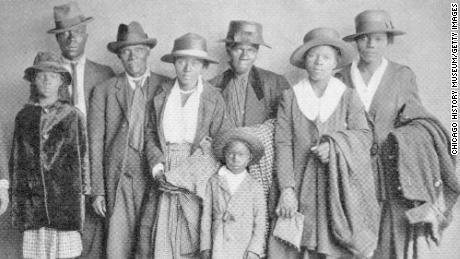

Some fled the South for the ‘warmth of other suns’

The segregated nature of Mississippi’s politics is partly what led to the first Great Migration. Much of the South was an apartheid state where Blacks could lose their jobs or get killed for trying to vote. They could even be killed for whims such as “reckless eyeballing” — looking at a White person the wrong way.

That fear stayed with many Blacks long after they left the Deep South.

“My mom still doesn’t come here now, and she’s from Virginia,” says Burton, who lives in a suburb of Atlanta.

An estimated six million Blacks left the South for the North between 1915 to 1970. They hopped on railway cars from states like Mississippi and Louisiana to head for factory jobs in cities like Chicago and Detroit. This epic migration was captured most memorably in a 2010 book by Isabel Wilkerson, “The Warmth of Other Suns.”

Wilkerson’s book title is based on a poem by the Black author Richard Wright, who moved from the South to Chicago and wrote he was “taking a part of the South to transplant in alien soil,” to “bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns and, perhaps, to bloom.”

For many Black people in Georgia, part of the thrill of this week’s victories is that they are finally seeing the political winds bend in their direction.

Warnock is the first Black man ever elected to the Senate from Georgia. Until this week, Republicans

held every statewide elective office and majorities in both houses of the legislature. Until last November, when Biden edged President Trump here, Georgia was a reliably red state.

“There’s no going back,”

said Jacquelyn Bettadapur, chairwoman of the Democratic Party in Cobb County, a suburban Atlanta county that was once staunchly conservative. “A Democrat would be a fool not to play in Georgia going forward.”

Warnock evoked this triumphant mood when he cited his 82-year-old mother, the Rev. Verlene Warnock, who spent her summers picking cotton and tobacco in the fields of southern Georgia.

“Because this is America,” he said, “the 82-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else’s cotton went to the polls and picked her youngest son to be a United States senator.”

Why Georgia’s runoff victories are bittersweet

And because this is America, one Black man in Atlanta couldn’t help but think this week of an American hero who saw the best and worst of the nation.

Bernard Lafayette was friends with John Lewis, the former civil rights icon who died last July. As a longtime civil rights activist, Lafayette was also friendly with the Rev. C.T. Vivian and the Rev. Joseph Lowery, two other giants of the civil rights movement who also died in 2020.

All three men were fixtures in Atlanta and around Georgia. None of them lived to see Warnock elected.

Lafayette, 80, was particularly close to Lewis. The two men were college roommates and risked their lives as leaders of the student sit-in movements of the early 1960s and the

Freedom Rides, the movement to desegregate interstate bus travel.

Lafayette said he received a call from Lewis just five days before he died. The weakened congressman said to him, “I just wanted to hear your voice.”

When Lafayette heard about this week’s dual Democratic victories in Georgia, he thought of his departed friend.

“John Lewis would have been very elated,” he says. “He’s smiling right now and celebrating.”

So are many other Black residents of Georgia. But some of that elation is tempered by what may come.

During the same week that Black voters in Georgia delivered the Senate to Democrats, the Republican-controlled Georgia legislature

proposed laws that would make it harder to vote.

They said they wanted to prevent voter fraud, even though no credible evidence of widespread voter fraud has been found.

But Burton says Black voters in Georgia won’t turn back now. They have a taste of national political power. Many are already gearing up for what they expect to be the next big contest: Abrams running for Georgia governor in 2022 in a potential rematch with Gov. Brian Kemp, who narrowly beat her in a controversial 2018 race.

“What’s next? Stacey in the governor’s mansion,” Burton says. “We’re not going to let up.”

Burton and other Black voters will have plenty of company. As more Black Americans return to cities like Atlanta, they will continue to reshape politics in the South. They will join people like Burton who no longer need to go North, like their ancestors, to feel the warmth of other suns.

The message they sent from this week’s Georgia runoff election is simple: Our political power is starting to bloom again.