Mahatma Gandhi, an icon of nonviolent resistance who helped lead India to independence by force of will and strength of mind, rather than physical power, might not seem like a person preoccupied with corporeal matters.

In fact, Gandhi endlessly monitored his own blood pressure and had a “preoccupation with blood,” as MIT scholar Dwai Banerjee and co-author Jacob Copeman write in “Hematologies,” a new book about blood and politics in India.

Gandhi believed the quality of his own blood indicated his body’s “capacity for self-purification,” the authors write, and he hoped that other dissidents would also possess “blood that could withstand the corruption and poison of colonial violence.” Ultimately, they add, Gandhi’s “single-minded focus on the substance was remarkable in its omission of other available foci of symbolization.”

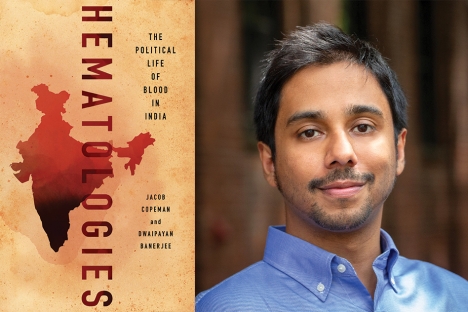

If India’s most famous ascetic and pacifist was actually busy thinking about politics in terms of blood, then almost anyone could have been doing the same. And many people have. Now Banerjee, an assistant professor in MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society, and Copeman, a senior lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Edinburgh, look broadly at the links between blood and politics in “Hematologies,” recently published by Cornell University Press.

The book encompasses topics as diverse as the rhetoric of blood in political discourse, the politics of blood drives, the uses of blood in protests, and the imagery used by leaders, including Gandhi. Ultimately, the scholars use the topic to explore the many — and seemingly unavoidable — divisions in Indian politics and society.

For progressives wanting a pluralistic society, the rhetoric of blood has often been used to claim that people are essentially alike, no matter their religious or social differences. The notion is that “if you bleed and I bleed, we bleed the same color,” Banerjee says. “In the first few decades after India’s independence [in 1948], there was this idea that blood would unite all different kinds of Indians, and all these years of caste discrimination and colonial rule that had divided us and pitted us against each other would now be fixed.”

But the idea that different groups in society are divided by blood is also a powerful one, as Banerjee and Copeman note, and as India has moved away from pluralism in recent years, a very different rhetoric of blood has regained popularity. In this vision, different ethnic or religious groups are separated by their blood — and bloodshed may be the price for disrupting this supposed order.

“What’s become clear in the last five years is that this other valence of blood, that it divides us [and has] more violent connotations, is becoming much more inescapable now,” Banerjee says.

That is not what many expected in an age of technocratic and globally integrated economics, but it is a reminder of the power of narrow forms of nationalism.

“The whole idea of modern politics is supposed to be this transcending of blood [and] ethnic religious nationalisms, and that modern contractual politics is based on less biologically based forms of cohabitation,” Banerjee says. “That never seems to work out.”

Focused on Northern India, where Banerjee and Copeman did their fieldwork over several years, “Hematologies” explores these issues in everyday life and with fine-grained detail. As they examine in the book, for instance, political protesters sometimes use their own blood as a medium of expression, to signal both their own commitment and the serious of the issues at hand.

The authors look closely at an advocacy group for survivors of (and residents near) the site of 1984’s Bhopal chemical plant disaster, which wrote a letter in blood — collected from young adults — to the prime minister, asking for a meeting. Somewhat similarly, Indian women have gained attention using blood in the imagery they have created to accompany campaigns against sexual violence and gender discrimination. In so doing, “they deploy the substance as a medium of truth and a mechanism of exposure,” Banerjee and Copeman write.

Even blood drives and blood donations have intricate political implications that the authors explore. While supposed to be separated from politics, some blood drives are de facto rallying points in campaigns and expressions of political solidarity. Blood drives also serve to highlight a tension between science and politics; some medical experts might prefer a more steady flow of donated blood, while a politically prompted donor drive can produce an unnecessary surge of blood.

“Educational campaigns talk very strategically about this,” Banerjee says.

While writing the book together, Banerjee and Copeman initially had slightly different research areas of interest, but before long both discovered they were fully engaged with a whole range of connections between blood and politics.

“To me, it seemed we found this synergy in the way we worked and thought, and I can’t think of a moment where we ever significantly doubted the process we were going through,” says Banerjee. “Constantly bouncing ideas off another person keeps it interesting.”

“Hematologies” has drawn praise from other scholars in the field. Emily Martin, an anthropologist at New York University, has called it “an extraordinary exploration of the multitudes of meanings and uses of blood in northern India.”

Banerjee notes that India is hardly unique in the way the rhetoric of blood spills into politics. “There is a global similarity in which blood is always a political substance,” he notes, while adding that India’s own unique history gives the subject “its own flavor” in the country.

Ultimately the story of blood being traced in “Hematologies” represents a distinctive way of examining divisions, conflicts, and tensions — the very stuff of contested politics and power.

“Again and again we see that blood always gets caught up with division and divisive politics,” Banerjee says. “It never escapes politics in the way that reformist and secular imaginations hope it will.”