A prospective COVID-19 vaccine touted as a made-in-Canada response has begun human clinical trials in Toronto, and the company says it’s already preparing a followup that will target more infectious variants.

Providence Therapeutics of Calgary says if all goes well, it could start manufacturing millions of doses of its first prospective vaccine by the end of the year, guaranteeing a Canadian stockpile that wouldn’t be subject to global supply pressures or competition.

That’s if the formulation proves safe and effective, of course.

Among the challenges of developing a vaccine amid a raging pandemic is the uncertainty of how more infectious variants now emerging will complicate the COVID battle.

Even if successful, by the time Providence Therapeutics releases its vaccine hopeful, much of the country could be in the throes of a more infectious virus that does not respond to this formulation, said company CEO Brad Sorenson.

“We don’t believe that this is going to be resolved by a single vaccine,” said Sorenson, whose biotech also produces a personalized mRNA-based vaccine against cancer.

It’s a challenge now facing Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which have each said its products appear to respond well to the variant initially identified in the United Kingdom, and to a lesser degree, the variant first detected in South Africa.

Moderna said earlier this week it plans to test two booster vaccines aimed at the variant associated with South Africa.

Sorenson said Providence is already internally testing a vaccine candidate that targets the variants, and he hoped to begin clinical trials by the end of the year.

“We believe that there’s going to be a need to be in a position of readiness to be able to respond as these variants are coming up, and to be able to make sure that we have that capacity.”

That doesn’t mean Providence is changing production runs just yet.

Sorenson said the immediate focus is to establish the safety and efficacy of its COVID-19 vaccine, dubbed PTX-COVID19-B and designed in the early days of the pandemic last March.

It uses messenger RNA technology and focuses on the spike protein located on the surface of a coronavirus that initiates infection, similar to the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna products.

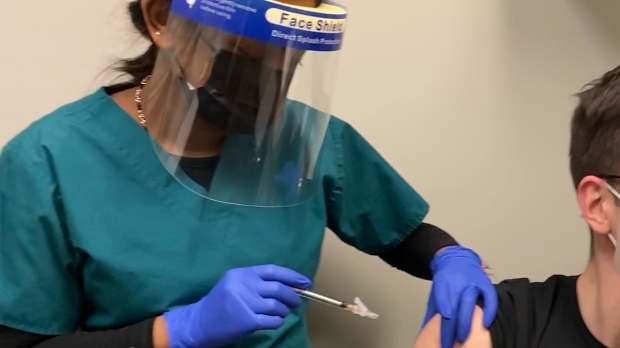

The trial involves 60 healthy volunteers aged 18 to 25 who will be monitored for 13 months, with the first results expected in February.

The subjects are divided into four groups of 15, three of which will get three different doses. The fourth group gets a placebo.

Sorenson said immediate pandemic efforts should be focused on the novel coronavirus currently devastating many parts of the country.

“It’s a matter of capacity. Right now these variants are there, they’re concerning, and we’re keeping a close eye on it, but that’s not predominantly what the needs of the population are,” said Sorenson.

“Right now the needs of the population are still tied to the primary spike protein virus that’s out there and is ravaging around the world.”

Sorenson said his next vaccine candidate takes a broader approach by attempting to elicit a T-cell response, thereby creating a longer-term vaccine “and cover what we believe would be a lot more variants.”

“We have to prove it out, but we believe that if we are successful that it will allow for a much more durable immunity and a much broader immunity.”

The other goal is to prepare for large-scale manufacturing in Calgary, if all goes well with the trials and approval process.

Sorenson said doses for the Phase 1 trial are being made in Toronto, but the plan is to commercially manufacture the completed vaccine through a contract with the Calgary-based Northern RNA Inc.

That won’t be up and running by the end of the year, Sorenson allowed, so the short-term plan is to send raw materials made in Canada to a plant in the United States that would make the commercial product.

Eventually, the whole process would be completed in Canada, he said.

“We’re building the entire chain within Canada, so we’re not going to run into a problem where this particular input into the vaccine is unavailable,” he said.

Much of this also depends on financial support from the federal government, Sorenson added.

While the National Research Council of Canada has backed Phase 1 trials, Sorenson said he’s awaiting word on further support. He’d also like Ottawa to back Providence’s efforts to address the new COVID variants.

“They’ve already recognized the importance of mRNA technology. What they don’t realize is the power of mRNA technology to be responsive to these challenges that are coming up,” he said.

“Hopefully the politicians and the people that cut the cheques and write the policies that give direction to the bureaucrats will hear that and we’ll start seeing a more concerted approach that looks at a fuller picture.”

Pending regulatory approval, Sorenson said a larger, international Phase 2 trial may start in May with seniors, younger subjects and pregnant people, followed by an even broader Phase 3 trial.

The Providence project is just one of several Canadian efforts underway to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

The biopharmaceutical company Medicago, based in Quebec City, began clinical trials on its plant-based candidate last July. If successful, the company has said manufacturing would take place in Durham, N.C., until it can complete a large-scale manufacturing facility set for Quebec City.

And last month, Health Canada gave the green light to the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) at the University of Saskatchewan to launch its Phase 1 clinical vaccine trial.

Infectious disease expert Jason Kindrachuk, who works with VIDO but is not involved with its vaccine candidate, said a varied vaccine strategy will be key to controlling the pandemic.

“Vaccines are not necessarily a one-size-fits-all and maybe with this pandemic, people are getting a greater appreciation for some of the logistical hurdles of trying to transport vaccines. Cold chain storage is not something most people knew about or thought about prior to COVID and everybody in the community now I think has heard about it,” said Kindrachuk, a visiting scientist from the University of Manitoba and Canada Research Chair.

“This is something that, in regards to vaccine development, we really have to put a lot of thought into as a research community because of the fact that we have to make vaccines that are accessible for the communities that are ultimately going to be treated with them.”

Ontario Health Minister Christine Elliott acknowledged Tuesday that appetite was strong for a homegrown answer but noted Providence was still a considerable ways from offering a viable option.

“First it has to go through the appropriate approval process, go through Health Canada to make sure that it’s going to be satisfactory and safe and efficacious,” said Elliott.