Art

Acceptance, not awareness, key to fostering inclusivity in the arts

|

|

Ammanda Zelinski has always gravitated toward singing, dancing and performing.

“She’s never had much for other interests,” said Ammanda’s mother, Kim Zelinski.

“From the time she was very small, it wasn’t even safe to stand between her and an empty stage.”

Ammanda’s first taste of creative success came when she was about seven and submitted a poem that was chosen to be published in a book.

“I won 50 bucks from there. For a second grader, that’s big money,” Ammanda said.

Since then, the 27-year-old Regina woman has experienced many special moments as an artist.

Ammanda was diagnosed with autism just before her third birthday.

She says her parents were thrown for a loop, but they were told she could still lead a long and independent life, with the proper supports in place.

One place that provides support is the Autism Resource Centre in Regina. Diandra Nicolson, an employment co-ordinator there, works with young adults after high school to figure out what kinds of jobs they might be interested in and help them reach their goals.

“They are the most dependable employees. Since they prefer their routines so, like, strict and scheduled, [they’re] always going to show up on time,” Nicolson said. “They bring a unique perspective to things.”

Making friends wasn’t always easy for Ammanda. She says she often felt a step behind socially, but that changed as she grew more involved in the artistic community.

“Theatre definitely did help me with my communication skills,” Ammanda said. “Pretty much all of performance in general — acting, singing, dancing — it all goes into one.”

Ammanda’s performing earned her scholarships. In addition to earning her bachelor of arts at the University of Regina, and performing in commercials and film, Zelinski has worked with Listen to Dis’, Saskatchewan’s only arts organization led by and for people with disabilities.

Traci Foster is the founder and artistic director of Listen to Dis’. The group’s mandate is to shift the way people perceive disability and create understanding of, and appreciation for, “crip art, mad art, and disability culture.”

She says it’s important for people in the arts to have lived experiences and varying perspectives, whether they are neurodiverse or not.

Foster also says it’s important that everyone gets paid for their work.

“[People with disabilities] were still maybe aligned a little bit with, like, ‘somebody’s doing me a favour if they let me come and work with them’, as opposed to building the confidence to understand the talent and the skill that they had,” Foster said.

Ammanda wants to keep creating inclusive art using her perspective and life experience.

“With more acceptance of autism — not awareness, acceptance — we can continue pushing the narrative forward.”

Mark Claxton, an actor and executive director of the Saskatchewan Association of Theatre Professionals, says parents should be delighted if their children are interested in the arts.

“It means their kids are legitimately curious about the world, really intelligent, you know, and want their lives to be meaningful,” Claxton said. “Who doesn’t want that for their kid?”

Ammanda’s mother Kim agrees, and is proud of everything her daughter has accomplished through passion, hard work and determination.

“I definitely need her as much as she needs me. I always will,” Kim said.

CBC’s Creator Network is looking for emerging content creators to make short videos (5 minutes and under) for an 18 to 30-year-old audience. Content creators can be writers, filmmakers, vloggers, photographers, journalists, artists, animators, foodies or anyone else with a compelling idea and visual plan for bright and bold content. Learn how to pitch your idea here.

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

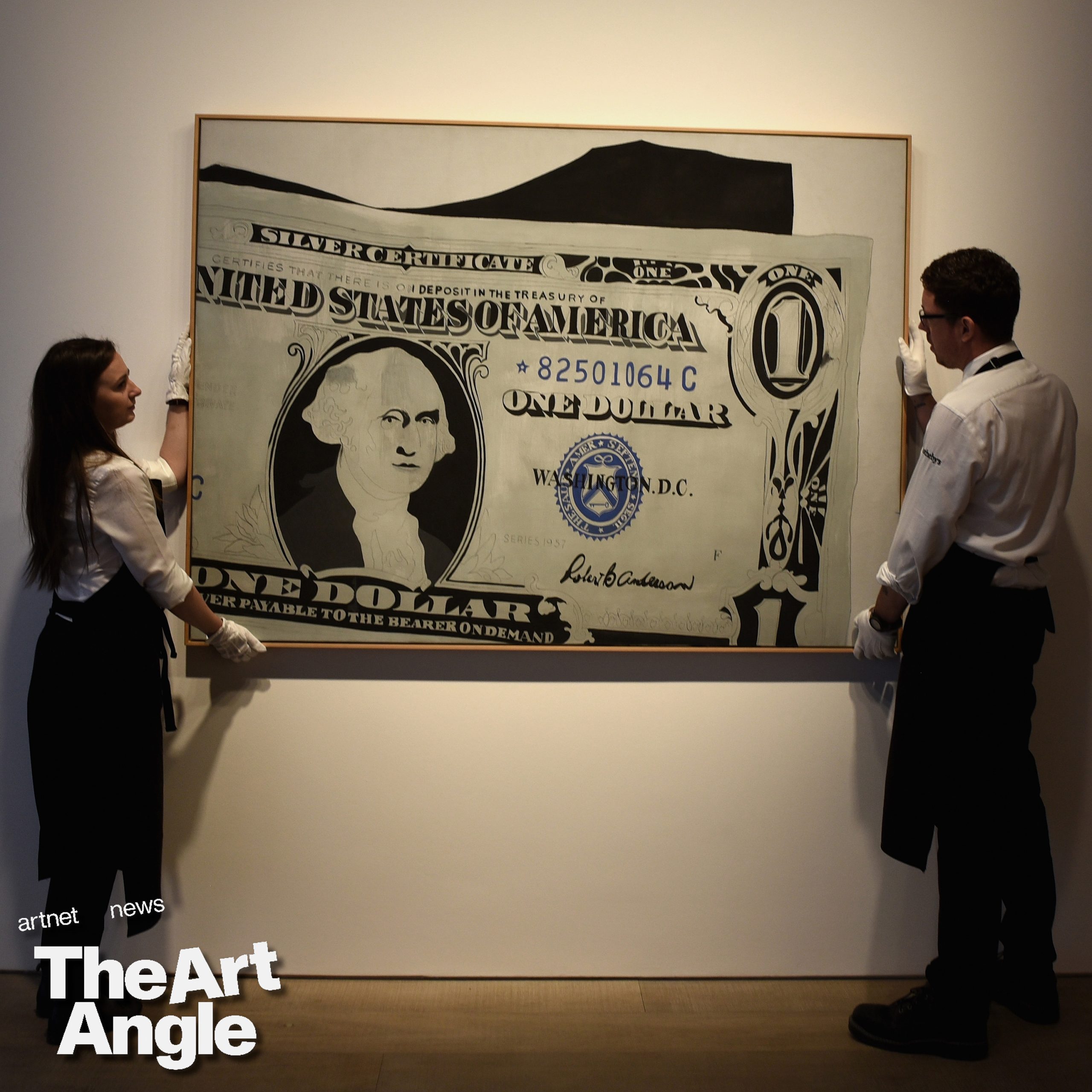

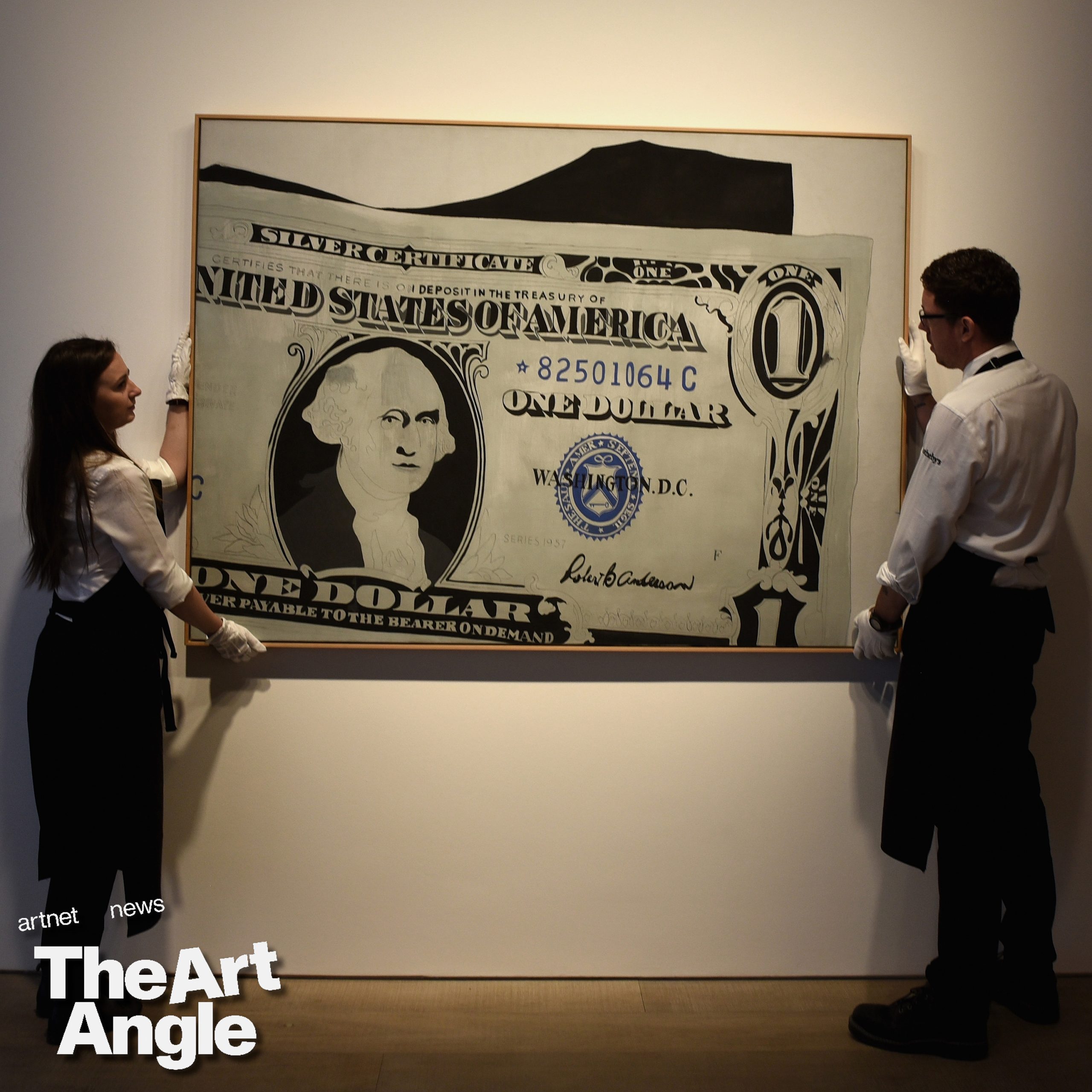

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media14 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media16 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment14 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

-

Investment24 hours ago

Investment24 hours agoWant to Outperform 88% of Professional Fund Managers? Buy This 1 Investment and Hold It Forever. – The Motley Fool

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoToronto reports 2 more measles cases. Use our tool to check the spread in Canada – Toronto Star

-

Business15 hours ago

Gas prices see 'largest single-day jump since early 2022': En-Pro International – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Real eState6 hours ago

Botched home sale costs Winnipeg man his right to sell real estate in Manitoba – CBC.ca