Photo Kira Perov/©Bill Viola Studio

‘Make it strange” is one of the slogans of modernism. The National Gallery’s show After Impressionism makes modernist art itself strange, by seeing it from the past – the Victorian salons where this revolution in the arts actually started. It is a flawed show but one I found hard to leave. European art in the 1880s and 1890s hurtles towards the “modern” before your eyes, yet also burrows away into recesses of nostalgia and pastoral – and you lose yourself, as modernism wants you to.

You can cut a line through the exhibition and follow the high road of the new, ignoring all those odd byways. Simply rush from Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire with its hypnotic field of broken, tentative, obsessive dapplings held together by an iron intellect, straight to Pablo Picasso’s 1910 portrait of Wilhelm Uhde. This writer and collector is the last man, the last bourgeois individual, in Picasso’s revolutionary portrait. His cartoonish features, pinched and prissy over a stiff wing collar, are disintegrating into a crystal cavern of invisible structures made suddenly visible. This is the maze of “cubism”, that takes its start from Cézanne’s analysis of vision. This is where, by 1910, the most radical art stood – on the edge of a quantum universe.

Cézanne initiated that. The biggest shock of the show is how much more serious he is than its other two supposed heroes, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Yes, that’s right – better than Van Gogh. That is the clear conclusion of a display of five works by each, facing each other. Vincent’s paintings are touching, intimate, yet traditional compared with Cézanne’s dismantling of art and nature. Gauguin meanwhile is brittle and strident, his art always trying too hard to be “mysterieux”.

Picasso is the gifted pupil Cézanne never met. You can see that by darting to the end to see Picasso’s Woman with Pears, a portrait of his lover Fernande Olivier done in 1909. Is it a portrait? Fernande’s head is massive and industrial. Like a taut spiralling girder for a modernist monument, her neck tendon shoots up in a curve of electrifying torsion. Her eyes are diamond studs in a face of jarring planes, her hair a heap of black croissants. Yet beside this immense mask of the new age are perfectly recognisable, simplified pears on a table. They are Cézanne pears. You can go back to room two and check, by comparing them with the fruits in Cézanne’s Sugar Bowl, Pears and Tablecloth.

This is the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death. Modernism, the movement that sought to remake everything in art from a new, primal beginning, belongs to history now, but it does not get old. That is because it takes apart centuries of tradition in the name of a more basic truth. All the artists here are looking for truth, even if they don’t all find it.

after newsletter promotion

They saw this deeper human reality as primal. “Primitif”, to be exact. Modernism was born in Europe’s age of empire. From Tahiti in 1892, Gauguin sends the poet Stéphane Mallarmé a wooden carving named after Mallarmé’s poem The Afternoon of a Faun. His extraordinary object merges classical myth with racial stereotypes to portray a goat-legged Polynesian man desiring a Tahitian nymph. You can’t fault Gauguin’s clarity. The sensual Arcadia that Mallarmé conjures is a real place in the Pacific, says Gauguin.

Even as Europe conquered or exploited much of the world in the 1800s, the “primitive” art that came streaming on to its markets exacted an aesthetic revenge. Artists preferred it to their own “civilised” conventions. When the Belgian artist James Ensor depicted a variety of non-European masks in Astonishment of the Mask Wouse in 1889, Belgium was running the most brutal of colonial businesses in the Congo, working thousands of people to death. André Derain owned a Fang mask from central Africa that directly influenced him and his friends including Matisse and Picasso. Derain’s 1906 painting The Dance portrays fantasy dancers, one with a painted body, another with a shadowed, mask-like face, another in an ancient Greek dress, in a golden paradise where they gyrate with unrepressed abandon.

If the first moderns sought to be “savage”, they also loved sex. This was the age of Sigmund Freud. Matisse’s Dance – no, not that one: who knows when any of us will see his masterpiece in the Hermitage again? – but a carved wooden relief from 1907, releases raw, ecstatic sexuality in its wild naked romp. And this is just one of the exhibition’s nude explosions. In Berlin they were fixated on flesh – tottering, quivering masses of it. Lovis Corinth’s Nana, Female Nude looks as if she’s been left over from the recent Lucian Freud show in this same space. Corinth’s Perseus and Andromeda, in which a knight in armour unveils a female nude, may not seem very modern at all: but nor does Wagner until you hear him.

Why does Degas make it into this show while other impressionists get left behind? Sex. Degas pervs with the best, or the worst. Facing Gauguin’s pensive isolated tropical nude Nevermore are his painting of a woman lost in red ecstasy as her long hair is combed, and pastel of a naked model curled up reading.

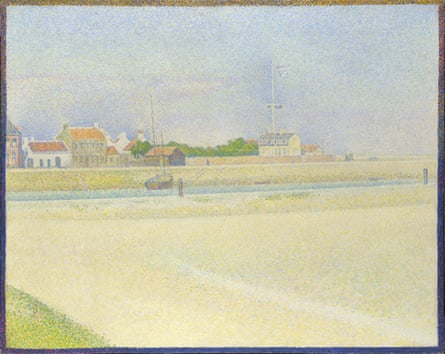

It’s a shame Pissarro doesn’t make the cut when he worked so closely with Cézanne and later helped pioneer the divisionist or pointillist style. It is equally baffling that Seurat’s compelling essays in this perceptual art get less space than Paul Signac’s painting-by-numbers attempts. And Munch is shoved into the Berlin section, oddly, which doesn’t stop The Death Bed harrowing your heart.

I could go on, and get cross, but it would miss the point. For some of the unevenness is in the period itself. What this show reveals is that modernism was an end, as much as a beginning. Five hundred years of European pictorial art – the very tradition the National Gallery displays – were breaking and decaying, and what was born in their stead was difficult, elusive, as daunting and inescapable as Picasso.

A new art installation now towers over Vancouver’s Hastings Park fields in celebration of the city’s history of spectators and sports.

Home + Away is a sculpture by Seattle artists Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo of Lead Pencil Studio, which opened Monday in the southeast end of the historic park.

Open Gallery

6 items

It’s a 17-metre-tall structure that resembles a narrow set of bleachers — similar to the stands of the Empire Stadium, which stood on the site of the park from 1954 to 1993 and hosted The Beatles, among many others. It recalls a covered ski jump that stood there in the 1950s and the nearby wooden rollercoaster at the PNE.

The city says the public is invited to walk the stairs and sit on the benches.

“In addition to being visually striking, this artwork is intended to be ascended, sat on and experienced. It offers exciting experiences of height and views and provides 16 rows of seating for up to 49 people, making for a unique spectator experience when watching events at Empire Fields,” the city said in a release Monday.

The idea for the park to include public art was outlined in the Hastings Park “Master Plan,” first adopted by the city in 2010. The city says Han and Mihalyo first presented their design in 2015.

“It’s wonderful to see this piece realized within the context of such a well-used public space,” said Han.

“Home + Away was inspired directly by the site history of spectatorship, and we hope it will connect Hastings Park users to that history and the majestic views of the environment for many decades to come,” added Mihalyo.

The artwork features a large light-up sign, in the style of a sports scoreboard, that reads “HOME” and “AWAY.”

Bill Viola, whose decades-long engagement with video proved vital in establishing the medium as an integral part of contemporary art, died on July 12 at his home in Long Beach, California. He was at 73 years old. The cause was complications related to Alzheimer’s disease. The news of his passing was confirmed by James Cohan Gallery.

Viola’s works are centered around the idea of human consciousness and such fundamental experiences as birth, death, and spirituality. He delved into mystical traditions from Zen Buddhism to Islamic Sufism, as well as Western devotional art from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in his videos, which often juxtaposed themes of life and death, light and dark, noise and silence. These explorations were achieved by submerging viewers in both image and sound with cutting-edge technologies for their time.

“I first used the camera and lens as a surrogate eye, to bring things closer, or to magnify them, to experiment with perception, to extend vision and make lengthy observations of simple objects,” Viola said in a 2015 interview. “Once you do that, their essence becomes visible. So I suppose I was always interested in the inner life of the world around me.”

Beginning in the 1970s, Viola created videotapes, architectural video installations, sound environments, electronic music performances, flat panel video pieces, and works for television broadcast—all of which expanded the scope of the medium and established Viola as one of its most notable practitioner.

Photo Kira Perov/©Bill Viola Studio

Bill Viola was born in 1951. He grew up in Queens and Westbury, New York, and attended P.S. 20 in Flushing, before receiving his BFA in experimental studios from Syracuse University in 1973. There, he studied with visual art with the likes of Jack Nelson and electronic music with Franklin Morris.

Following his graduation, between 1973 to 1980, Viola studied and performed with composer David Tudor in the music group Rainforest, which later became known as Composers Inside Electronics. He also worked as technical director at the pioneering video studio Art/tapes/22 in Florence, Italy from 1974 to 1976. During that time he encountered the work of other seminal video artists like Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman, and Vito Acconci.

Viola was subsequently an artist-in-residence at New York’s WNET Thirteen Television Laboratory between 1976 to 1983, wherein he created a series of works that premiered on television. He traveled to the Solomon Islands, Java, and Indonesia to record traditional performing arts between 1976 and 1977. Later that year, Viola was invited to show work at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, by cultural arts director Kira Perov, with whom he married and began a lifelong collaboration.

He was appointed an instructor in advanced video at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California in 1983. He was the Getty Research Institute scholar-in-residence in Los Angeles in 1998 and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2000.

In 1985, Viola received with a Guggenheim Fellowship for fine arts, and later that decade, in 1989, he was awarded the MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. His work was also featured in some of the world’s most notable exhibitions, including Documenta VI in 1977, Documenta XI in 1992, the 1987 and 1993 editions of the Whitney Biennial, and the 2001 Venice Biennale.

In 1995, he represented the United States at the 46th edition of the Venice Biennale. For the pavilion, Viola produced the series of works “Buried Secrets,” including one of his most known works The Greeting, which offers a contemporary interpretation of Pontormo’s oil painting The Visitation (ca.1528–30). The Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin and New York’s Guggenheim Museum commissioned the digital fresco cycle in high-definition video, titled Going Forth By Day, in 2002.

Viola’s work was the subject of a major 25-year survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1997, which subsequently toured internationally. His work has been the subject of major museum retrospectives in the years since, including at the Grand Palais in Paris (in 2014), the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence (2017), the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain (2017), and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (2019), as well as an exhibition pairing his work with that of Michelangelo at the Royal Academy of Art in London in 2019.

Viola is survived by his wife Kira Perov, who has been the executive director of his studio since 1978, and their two children.

“One thing that’s very exciting about video that has turned me on since I first saw this glowing image way back in 1970 is that it can be so much,” Viola said in a 1995 with Charlie Rose on the occasion of this US Pavilion at the Biennale. “Furthermore, what’s really exciting is I don’t think it’s been since really the Renaissance where artists have been able to use a medium that one could say is the dominant communication form in society.”

After grind of MLS regular season, Toronto FC looks forward to Leagues Cup challenge

CanadaNewsMedia news July 26, 2024: B.C. crews wary of winds boosting wildfires

Ontario expanding access to RSV vaccines for young children, pregnant women

In President Milei’s sit-down with Macron, Argentina says the leaders get past soccer chant fallout

People should stay inside, filter indoor air amid wildfire smoke, respirologist says

Federal grand jury charges short seller Andrew Left in $16M stock manipulation scheme

French train lines hit by ‘malicious acts’ disrupting traffic ahead of Olympics, rail company says

Work continues to clean second motor oil spill in river near Montreal