Art

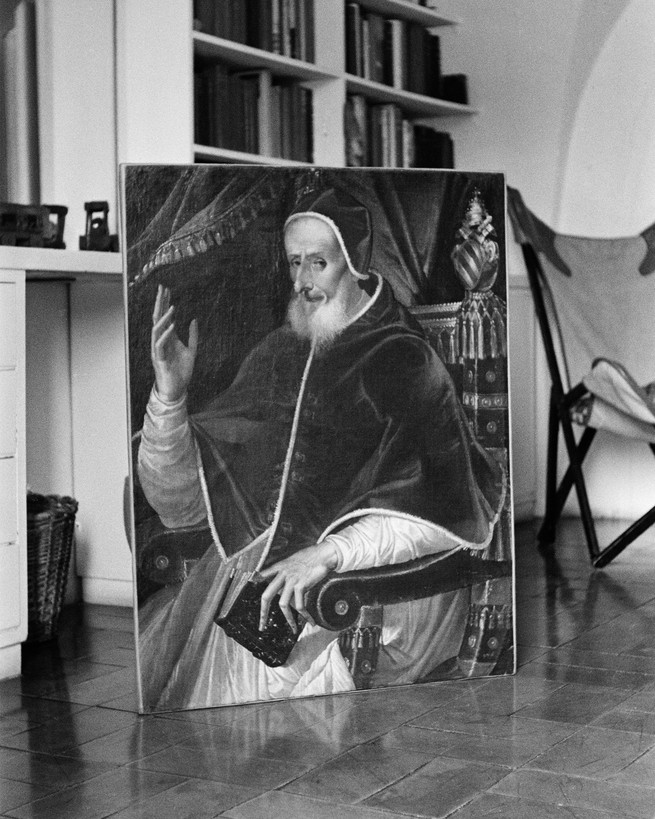

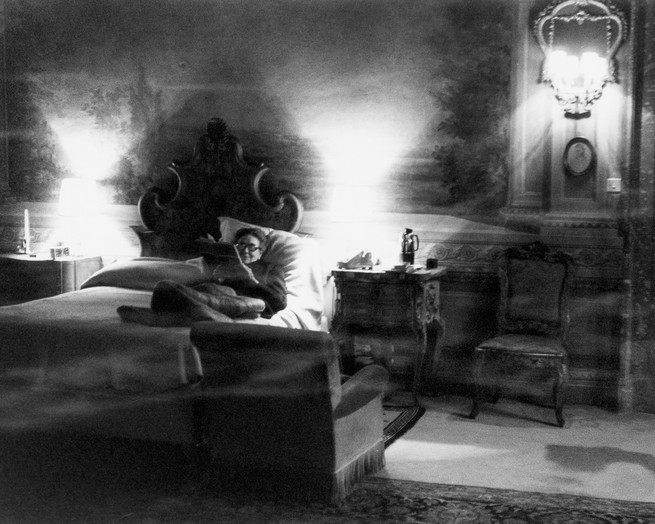

An American Art Critic’s 70-Year Love Affair With Rome

The New York–born critic and photographer Milton Gendel (1918–2018) lived in Rome for the last 70 years of his life, a quiet man observing the international swirl of artists, writers, aristocrats, and socialites of which he was himself a part—not to mention the ordinary hubbub of Roman life. Gendel died in 2018, not long before his 100th birthday. He would always say, of his seven decades in Rome, that he was “just passing through,” but his various homes in the city became a hub for figures including Antonia Fraser and Iris Origo to Princess Margaret and the collector Mimi Pecci Blunt. While personally unobtrusive, he was a shrewd listener, seemed to know everyone, and found his way everywhere. Gendel left behind tens of thousands of photographs and 10 million words of diary entries chronicling the cultural and social scene at the intersection of the American Century and la dolce vita. A collection of Gendel’s words and pictures, excerpted below, will be published tomorrow.

Rome. Monday, November 13, 1967

Lunch at Piazza Campitelli. Walk to St. Peter’s. After two or three years of having the nave encumbered with seats—for the Council—the church looks as it used to do. What balls was taught about the interior. [The art historian Everard M.] Upjohn at Columbia used to say with conviction that the space had been falsified by the decorations. The mosaics and sculptures and the architectural details were out of scale, and thus one had no real idea of the vast proportions of the building. This is not true. The visitors give the scale themselves immediately. The space is measurable, in terms of the familiar classical orders—it is clearly one of the largest such spaces in existence. Comparable—as a question of scale—is the Pantheon. The Upjohns were thinking of another kind of space and comparing it to that of St. Peter’s, to the disadvantage of the latter: the kinds of space developed from the end of the Imperial Roman times to the Gothic period. In other words, spaces created with unmeasurable elements, which give an illusion of incommensurable continuity.

It was a beautiful day, and at 4:00 the basilica was still very light. Beams striking down from the window over the front doors. Small figures of visitors moving along the great concourse that is the nave. I was reminded of Pennsylvania Station. It was wrong to destroy it. In a Communist country, it would not have happened for the same reason that so much was preserved in Italy: poverty.

Rome. Wednesday, December 6, 1967

At 8:00 to Carla Panicali’s. Dinner for the Calders. Very lively. Louisa Calder tangled with me at once on Vietnam, not realizing we were more or less on the same side. But that was partly because she has become so rabidly anti-government that she speaks well of de Gaulle. [Alexander] Calder a great, fumbling, white-haired thing in red shirt and red tie. Almost incomprehensible because he slurs his words since he had a heart attack. Slurred them before, too. But he is swift and piercing in his glances and seems to hear everything from all sides of the table. Horseplay with a datepick in the shape of a woman. Calder making a kind of mobile out of a fork and the pick and a date.

Rome. Wednesday, May 30, 1973

I had a long conversation with [the diarist and biographer] Iris Origo, whom I haven’t seen in a very long time … She spoke about her shyness, how she always felt out of things when she was a girl, especially as she had to change among three different cultures, American, Italian, and English. Bernard Berenson dismayed her once, when she was seventeen, and he hurled a challenging question at her across his salotto, which was full of people. She mustered her courage and answered—something about what she wanted out of life. That’s what I mean, he said with disdain, addressing the others—that is conventional thinking. She spoke about his diaries and his self-dissatisfaction. I said that it was a pity he had been born too soon; he was a generation or two out of line. Nowadays there would be very little conflict over his commercial operations and his scholarship. He didn’t have enough balance to see that he had gotten out of life the most that he was capable of. He was a worldling with dreams of monastic cloistered scholarship.

Rome. Thursday, August 23, 1973

To Carla Panicali’s to give her the transparency from Tom [Hess] for his article on Ad Reinhardt and to hear the story of the pope’s museum of modern art. Monsignor Pasquale Macchi, a polished little fellow, was the man behind the effort. He is a promoter and saw it as a good thing for the Vatican image. He succeeded in getting presents from artists and patrons. For instance, Gianni Agnelli has given a Francis Bacon, worth 150 million lire, and a Marino Marini worth 50. Carla had no plausible explanation as to why Gianni should have been so munificent. In secret, she told me that Macchi had bought some things from her directly—about 50 million lire worth—and she expected him to buy much more. This was not to be known publicly, as the Vatican preferred to play poor-mouth. In fact, at the opening the pope had referred to the generosity of friends of the Vatican who had made the museum possible “senza intaccare le finanze traballanti del Vaticano” [without affecting the shaky finances of the Vatican]. There was a suspicion of general suppressed laughter, said Carla.

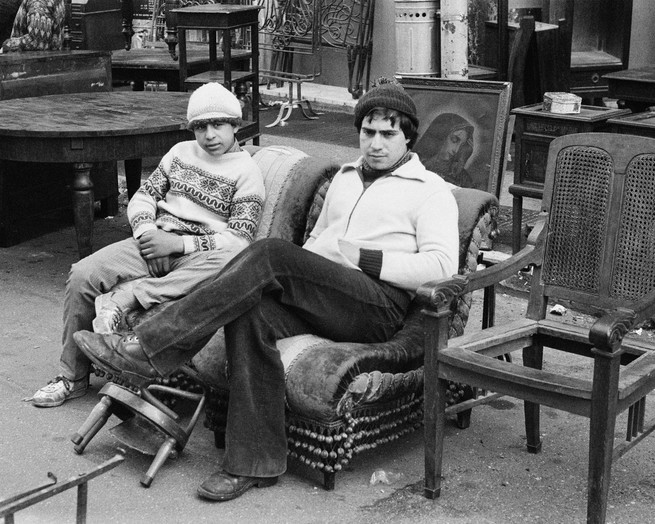

Rome. Saturday, February 9, 1974

Josephine [Powell] drove out with me to some junkyards she knew about. The best was a large area off the Via Appia Nuova, on the Raccordo Anulare, to the left. A monumental woman … dominated the yard from a snug furnished hut. Outside was a colossal wrought iron lantern with colored glass—something from a turn-of-the-century theater or department store. I priced a spiral staircase (180,000 lire), a straight iron ladder (50,000), some marble—white—about 25,000 for enough to make a fireplace. Josephine priced a four-wheeled cart of silvery old wood—70,000 lire.

But the prize of the junkyard was a group of toilet fixtures—a vast porcelain bath—oval—and another smaller one, a sink on a pedestal and a neoclassic toilet bowl. The woman owner made an impressed face when I asked the price. Quella è roba buona … la vasca più grande era del Duce [That’s good stuff … the bigger tub was Mussolini’s] …

On the way back to Rome, we stopped at a stone yard to price slate and peperino. A man with a mustache gave me the various prices—a beautiful dark pietra serena came to 9,000 lire a square meter; green marble, 16,000 … He also had rosa di Francia, a pretty pink marble, and many kinds of travertine. He asked me whether I was an artist, [and] when he heard that I was a giornalista, he said that he hoped I did not pay attention to the clothes a person wore—che non bada ai panni—and got me into his field house, where he showed me a book with a reproduction of a confused surrealist painting he had done. His name is Pasqua Pierini, and he was eager to have a conversation about art. I was not and tried to show that I was really an undereducated American and wasn’t up to a metaphysical conversation.

He became more animated, though, and pronounced in a D’Annuzian way on the burning fires of creativity.

Rome. [Undated] 1980

Alex and Tatiana Liberman expansive at the Rally Room of the Grand Hotel. The fashion shows were over, and you could breathe again, said Alex. Why, yesterday this room was packed with fashion people, and now they’ve all gone. I ate gamberetti and spigola and raspberries. Delicious food. Alex sailed into Balthus. He was a phony painter, just as he was a phony aristocrat and phony everything. Tatiana liked his work but found it limited. Why was it so “frozen”? I cited Chardin, Poussin, Piero, Vermeer, putting Balthus in company that’s really a bit too good for him. Alex declared that he couldn’t stand the “literary” character of the work. He liked only abstract art. He sounded like an old manual of the old avant garde …

And what explained the grandiosity of Roman buildings? They had been to see the Palazzo Spada, at my suggestion. It was power, wasn’t it? Imperial power. But that collection of paintings was pathetic, said Alex. All second-rate. Rome was second-rate in its art, wasn’t it? There wasn’t a Louvre. I composed them a Louvre by imagining the Barberini and Corsini collections thrown together with the addition of the Galleria Borghese and the Doria Pamphilj and the Vatican and the Sistine Chapel and Raphael’s Stanze.

They didn’t seem to get the point, and I felt that they would go away repeating that art in Rome was mediocre. Despite my citation of the Masolino and Pinturicchio wall paintings and the Rubenses and other notable works in the churches. Caravaggio.

Rome. Thursday, March 17, 1983

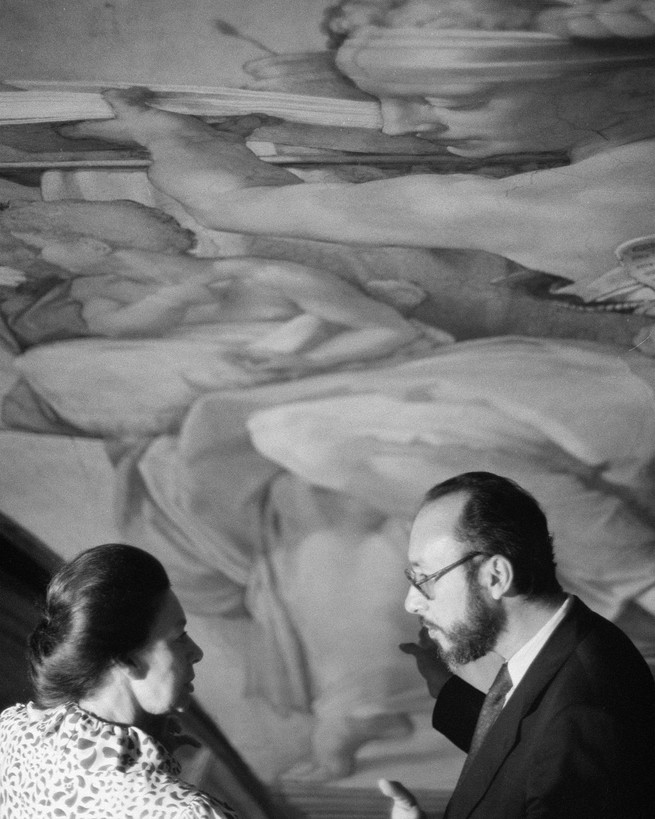

The cleaned Michelangelo frescoes in the Sistine Chapel are spectacular. What a transformation. The sixteenth-century palette becoming visible again. Basis for all the later Mannerist color. And the high relief of the figures and of the architectural elements when they are not flattened by accumulated grime.

Leo [Steinberg, an art critic,] spotted [Fabrizio] Mancinelli, the curator of Renaissance art, who was standing with [the art historians] John Shearman and Kathleen Weil-Garris observing the display of Raphael tapestries. Shearman had figured out the sequence of the tapestries that were made for Leo X and were full of Medici iconography and found where they were meant to go. He said, humorously triumphant, They fit!

A guard with a fierce manner but a twinkling expression was routing well-groomed elderly American ladies who were flashing away at the walls. Using flashes is not allowed in the chapel. Leo was very interesting on The Last Judgment. Michelangelo had rebuilt the wall so that it sloped in 30 cm. from the top to the bottom. Vasari, ridiculously pragmatic, according to Leo, said that this was done so that the dust wouldn’t gather on the surface of the wall. But it was to emphasize the invasion of the chapel’s space by The Last Judgment. The Church Triumphant replaces the Church Militant, and Christ himself takes the place of the popes. Hence there was no coat of arms of Paul III to replace the one of Sixtus IV corresponding to the one on the opposite wall that had been there. Michelangelo had progressively stepped up the scale of his figures toward the end wall. And the great moldings, for instance defining the corner lunettes, had been narrowed to the maximum.

And look at the cross that the stocky figure is planting—where is he setting it? On the cornice itself. That is Simon of Cyrene, according to Leo, and the painting is the first example in art history of the painted invading the real space.

This article was adapted from the book Just Passing Through—A Seven-Decade Roman Holiday: The Diaries and Photographs of Milton Gendel, edited by Cullen Murphy.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Art

Calvin Lucyshyn: Vancouver Island Art Dealer Faces Fraud Charges After Police Seize Millions in Artwork

In a case that has sent shockwaves through the Vancouver Island art community, a local art dealer has been charged with one count of fraud over $5,000. Calvin Lucyshyn, the former operator of the now-closed Winchester Galleries in Oak Bay, faces the charge after police seized hundreds of artworks, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, from various storage sites in the Greater Victoria area.

Alleged Fraud Scheme

Police allege that Lucyshyn had been taking valuable art from members of the public under the guise of appraising or consigning the pieces for sale, only to cut off all communication with the owners. This investigation began in April 2022, when police received a complaint from an individual who had provided four paintings to Lucyshyn, including three works by renowned British Columbia artist Emily Carr, and had not received any updates on their sale.

Further investigation by the Saanich Police Department revealed that this was not an isolated incident. Detectives found other alleged victims who had similar experiences with Winchester Galleries, leading police to execute search warrants at three separate storage locations across Greater Victoria.

Massive Seizure of Artworks

In what has become one of the largest art fraud investigations in recent Canadian history, authorities seized approximately 1,100 pieces of art, including more than 600 pieces from a storage site in Saanich, over 300 in Langford, and more than 100 in Oak Bay. Some of the more valuable pieces, according to police, were estimated to be worth $85,000 each.

Lucyshyn was arrested on April 21, 2022, but was later released from custody. In May 2024, a fraud charge was formally laid against him.

Artwork Returned, but Some Remain Unclaimed

In a statement released on Monday, the Saanich Police Department confirmed that 1,050 of the seized artworks have been returned to their rightful owners. However, several pieces remain unclaimed, and police continue their efforts to track down the owners of these works.

Court Proceedings Ongoing

The criminal charge against Lucyshyn has not yet been tested in court, and he has publicly stated his intention to defend himself against any pending allegations. His next court appearance is scheduled for September 10, 2024.

Impact on the Local Art Community

The news of Lucyshyn’s alleged fraud has deeply affected Vancouver Island’s art community, particularly collectors, galleries, and artists who may have been impacted by the gallery’s operations. With high-value pieces from artists like Emily Carr involved, the case underscores the vulnerabilities that can exist in art transactions.

For many art collectors, the investigation has raised concerns about the potential for fraud in the art world, particularly when it comes to dealing with private galleries and dealers. The seizure of such a vast collection of artworks has also led to questions about the management and oversight of valuable art pieces, as well as the importance of transparency and trust in the industry.

As the case continues to unfold in court, it will likely serve as a cautionary tale for collectors and galleries alike, highlighting the need for due diligence in the sale and appraisal of high-value artworks.

While much of the seized artwork has been returned, the full scale of the alleged fraud is still being unraveled. Lucyshyn’s upcoming court appearances will be closely watched, not only by the legal community but also by the wider art world, as it navigates the fallout from one of Canada’s most significant art fraud cases in recent memory.

Art collectors and individuals who believe they may have been affected by this case are encouraged to contact the Saanich Police Department to inquire about any unclaimed pieces. Additionally, the case serves as a reminder for anyone involved in high-value art transactions to work with reputable dealers and to keep thorough documentation of all transactions.

As with any investment, whether in art or other ventures, it is crucial to be cautious and informed. Art fraud can devastate personal collections and finances, but by taking steps to verify authenticity, provenance, and the reputation of dealers, collectors can help safeguard their valuable pieces.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours agoCavaliers and free agent forward Isaac Okoro agree to 3-year, $38 million deal, AP source says

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours agoLiverpool ‘not good enough’ says Arne Slot after shock loss against Nottingham Forest

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agok.d. lang gets the band back together for Canadian country music awards show

-

Sports5 hours ago

Sports5 hours agoArmstrong scores, surging Vancouver Whitecaps beat slumping San Jose Earthquakes 2-0

-

News20 hours ago

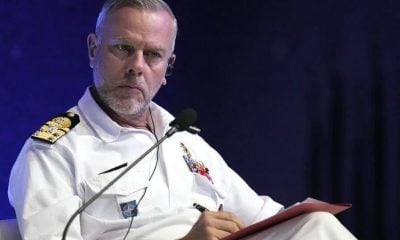

News20 hours agoNATO military committee chair, others back Ukraine’s use of long range weapons to hit Russia

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoWith a parade of athletes on Champs Elysées, France throws one last party for the Paris Olympics

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours ago‘Challenges every single muscle’: Champion tree climber turns work into passion

-

News5 hours ago

News5 hours agoAs plant-based milk becomes more popular, brands look for new ways to compete