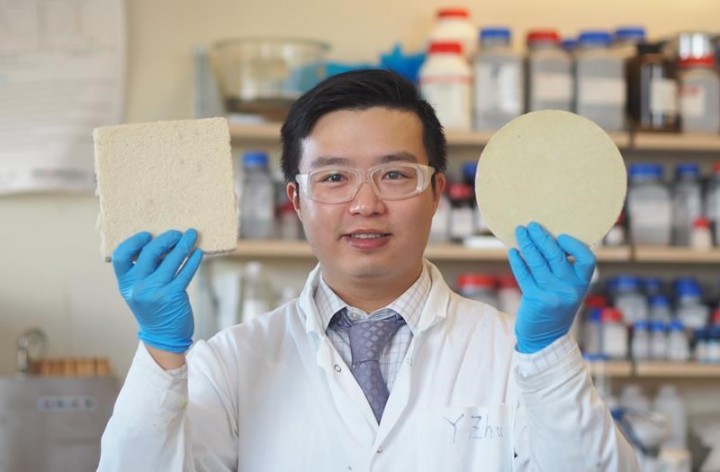

VANCOUVER — Styrofoam can take 500 years to decompose as it bloats landfills around the world, but new packing material called biofoam made of forestry waste can decompose in a matter of weeks, say scientists.

University of British Columbia researcher Feng Jiang says that’s a potential environmental boon, because Styrofoam currently fills up to 30 per cent of landfills.

“So, we have been doing a few tests, which is putting biofoam into the soil and then it started degrading … and after two months, it will be completely gone,” said Jiang, an assistant professor in the university’s faculty of forestry and the Canada Research Chair in sustainable functional biomaterials.

The biofoam project is a collaboration between the Wet’suwet’en First Nation in central B.C. and University of B.C. researchers.

The partnership came about three years ago when Jiang met Reg Ogen, president and CEO of the First Nation’s Yinka Dene Economic Development Limited Partnership, at an encounter arranged by the B.C. Forests Ministry.

Jiang and his fellow scientists listened as First Nation members described concerns about what to do with wood waste on their land.

Ogen said wildfires and infestations of mountain pine beetles in the 1990s and 2000s had created large amounts of waste that they wanted to be used in a meaningful way.

“We met with Dr. Jiang there and we looked at different ways of utilizing the wood waste and finally we came up with a product that I think we can do something good with. And hopefully, at the end of the day, to keep all of the Styrofoam out of the landfills and then make sure that we continue to protect Mother Earth,” said Ogen.

He said seeing waste transformed into a useful material brought a smile to his face.

Ogen hopes biofoam will create First Nations jobs that were lost when the pine beetle epidemic swept through their timber industry.

“One of our main goals is to make sure that our next generations are taken care of and made sure that they have good job opportunities,” he said.

“With this opportunity, we don’t necessarily have to look (only) at our backyard. There are other areas in Western Canada we could look at, even in the United States or overseas … I think there’s a great opportunity to make it a worldwide success.”

Biofoam’s texture is close to Styrofoam and can be similarly fashioned into different shapes. Its natural origins make biofoam slightly darker in colour.

While the specific ingredients remain a secret, it’s made by grinding the wood into fibre to create a slurry, then adding non-toxic chemicals, and finally putting the mixture into an oven at 80 C.

Jiang said the process is similar to baking.

“After a couple of hours, we take it out, just like a big cake,” said Jiang.

Investors and manufacturers are now being sought to launch a pilot plant to produce biofoam in B.C. next year.

A side benefit of the project could be mitigating forest fires that are fuelled by wood waste, Jiang said.

The project’s intellectual property is shared by Jiang’s team and the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, UBC said in a statement.

Jiang said environmental sustainability is his passion, and although it isn’t realistic to substitute all plastics with natural fibres, he wants to stress what he called the three Rs: reusing, recycling and replacing plastics.

“Whenever I see a product in the market, I always think: can we replace it with natural fibre? I also keep asking my students the same question. Throughout my whole career, I want to use my knowledge and expertise to create something that is beneficial to the society and to the planet,” said Jiang.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 21, 2022.

This story was produced with the financial assistance of the Meta and Canadian Press News Fellowship.

Nono Shen, The Canadian Press