The Bank of Canada knows something about “unusual shocks.”

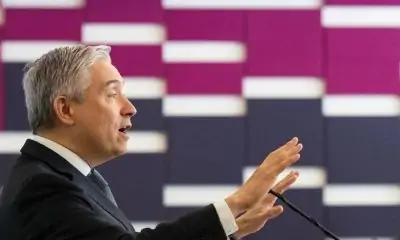

In 2003, David Dodge was in his second year as governor when the central bank confronted the SARS epidemic, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) in Alberta, a mass electricity failure across Ontario and severe forest fires in British Columbia — all at the same time.

Policy-makers in the fall of that year estimated that the combination of those calamities would slow the country’s annual rate of growth by nearly a percentage point in the second and third quarters. But, “given the temporary nature of these shocks, growth is expected to rebound in the fourth quarter,” the Bank of Canada said in its October Monetary Policy Report.

Economic growth did rebound, to an annual rate of almost four per cent, but the shocks from those events had taken a bigger toll than the central bank had realized heading towards the end of 2003. Dodge left interest rates unchanged in December, and then cut the benchmark rate by a quarter point in January, March and April. There were other variables at play by then, but one of the reasons for the stimulus was that the hole into which the Canadian economy had fallen was deeper than technocrats had realized in real time.

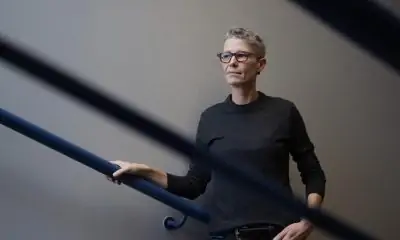

Timothy Lane, the longest-serving member of the Bank of Canada’s policy committee, was running around the world on behalf of the International Monetary Fund in 2003. For much of the next week, he will be spending time with Governor Stephen Poloz and the other deputies on the Governing Council to decide if they need to do anything to protect the Canadian economy from the coronavirus outbreak.

“Historical experiences are informative and we’ve certainly looked at that, but, of course, there are going to be differences in each episode,” Lane, who was named a deputy governor in 2009, said in an interview in Montreal on Feb. 24. “One obvious and major difference is that China is a vastly larger share of the world economy now than when we had SARS. But apart from that, it’s a question of how the behaviour might change and that’s something that might be different in different episodes and also depending on how the disease progresses.”

That answer might sound like a dodge, but consider how little headline trade numbers tell us about what’s happening on the ground.

Earlier this month, Statistics Canada said the number of Canadian companies exporting to China increased by more than 400 between 2016 and 2018. And yet, the 10 biggest exporters were responsible for half of those exports. Is Canada more exposed to China than it was two decades ago? Certainly. But what if most of that exposure is through a relatively small number of big, sophisticated corporations that possess the tools and financial might to cushion the blow? If that’s the case, then an interest-rate cut could be an overreaction.

“The historical guideposts are useful up to a point,” Lane said. “Ultimately, we are going to have to watch how things evolve.”

Lane was in Montreal to share the Bank of Canada’s latest thinking about digital currencies at a financial-technology conference hosted by CFA Montreal, and that’s what we talked about the most during a half-hour interview. (Watch this space.)

But with global financial markets plunging for a fourth day as COVID-19 spread to Europe and Iran, and as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned Americans to prepare for an outbreak, a few questions on what the Canadian central bank is thinking about all this were unavoidable.

Poloz and his deputies will release their next interest-rate decision on March 4. Most indicators suggest the economy barely grew in the fourth quarter, and that was before anyone knew about the coronavirus. It was also before some First Nations and their supporters blocked key railways for much of February. No one is talking about a recession, but no one is feeling good about the economy’s short-term prospects either.

“The coronavirus spread could lead us to revise down quickly our Canadian 2020 annual forecasts,” Sébastien Lavoie, chief economist at Laurentian Bank, said in a research note on Feb. 25. “This risk is unambiguously tilted to the downside.”

Lavoie, a former Bank of Canada economist, now sees little prospect for significant economic growth until at least March. Still, he said he was unprepared to predict an “insurance cut.” Poloz and his deputies opted against one of those last summer during the worst of the trade wars, and there probably isn’t enough reason yet to risk contributing to the current panic.

At the same time, economists at a handful of the biggest Canadian banks already thought the central bank would be forced to cut interest rates at least once this spring to offset waning consumer demand and weak exports. The idiosyncratic events generating headlines so far in 2020 only strengthen their case. So do the most recent indicators. Factory sales declined for a fourth consecutive month in December, and retail sales were flat at the end of the year. (To be sure, hiring remained strong, albeit less robust.)

Nothing Lane said will settle this debate.

If the Bank of Canada had a message for the markets, it would have added a section on the economy in his speech — and it didn’t. This round of policy deliberations will be done without the benefit of a revised forecast, since those are done only once a quarter and the last one was published in January, when policy-makers opted to leave the benchmark rate unchanged at 1.75 per cent.

“There have been those various pieces of news,” Lane said. “On the other hand, we’ve also had economic data coming in which has been not too much out of line with what we had been predicting. These recent events are too recent to show up in the data, so it’s really a question about how do we think about the risks going forward?”

•Email: kcarmichael@postmedia.com |