Art

Beaverbrook Art Gallery’s Tom Smart retires after long career in the arts

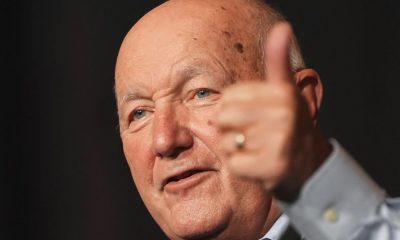

Tom Smart describes his humble beginnings in the art world as that of an art school dropout, a hippie, an actor, a scene painter, commercial artist and book illustrator.

“That’s kind of my bedrock — I was a rogue,” he said.

“I went back to school in English Lit, thinking through English Lit I could maybe start to understand … what creativity was, what artistic expression was, and is, and how I could find it in myself.”

And while for most of his career Smart surrounded himself with some of the greatest artists in the world as he led a number of major art institutions, including the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, he’s ready to get back to his roots.

“I wanted to paint more watercolours than I usually do, and I wanted to write … more about art and artists without getting bogged down in the administration of a big organization like the Beaverbrook,” Smart said, on Information Morning Fredericton, about his decision to retire.

“I just wanted to go back to what I really love and to really connect with the creative process.”

Smart had his last day on Friday as director of the Beaverbrook — a journey that began in 1989 when he took on his first job at the gallery as a curator.

He spent eight years there before moving to other galleries across Canada and the United States, including as CEO of the prestigious McMichael Canadian Collection, in Kleinburg, Ont., and at the Frick Art and Historical Center, in Pittsburgh, Pa.

He’s also written a number of books, including major works on Alex Colville, Mary Pratt and Miller Brittain.

In 2017, Smart returned to the Beaverbrook as director to focus on setting up the gallery for a sustainable future.

Smart said he believes he has achieved that, noting that the budget has grown over the last several years to allow for more activities, exhibitions and public outreach.

Under Smart’s leadership, the Harrison McCain Pavilion underwent an architectural redesign and construction process, which he said has also allowed for more public engagement.

Love the new, too

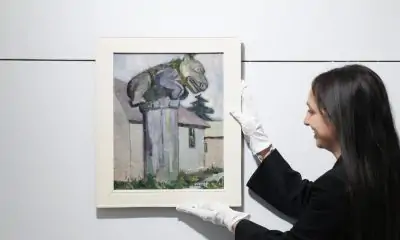

The gallery also was caught in a controversy in November when it sold an L.S. Lowry painting at an auction house in London that was part of Lord Beaverbrook’s original collection when he founded the gallery.

But Smart said that decision, to deaccession that painting and others, paid off.

He said some of the acquisitions with those funds have already been put on display, including one from artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun about climate change and forest fires.

“I knew that people connect very deeply to the collection,” said Smart.

“And I hope they love what we’ve brought into the collection, and we’ll be bringing into the collection, as a consequence of the deaccessioning process.”

He said he listened carefully to the criticism during that time and things may be more transparent in the future, but it will be up to the new director and curator going forward.

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery said in a news release that an international search is underway to find a replacement. In the interim, the gallery will be managed by a three-member team.

As for Smart, he is already preparing for retirement life and getting back to his first love.

For him, that begins at Go Home Lake in Ontario, where he has a cottage and red canoe waiting for him.

From there, he said he will often go up to Mason Island on the open water of the Georgian Bay, the inspiration for so many truly great artworks, including by the Group of Seven.

“We go … way out in the middle of the lake and I jump in and get the watercolours out on these rocks,” said Smart.

“It’s a very spare landscape, but it’s a landscape that you can imbue with your feelings and your ideas and your concepts about the here and the now.

“I’m looking forward to that very much.”

Art

$5.2m for a duct-taped banana: has the buyer of Maurizio Cattelan’s artwork slipped up? – The Guardian

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

- $5.2m for a duct-taped banana: has the buyer of Maurizio Cattelan’s artwork slipped up? The Guardian

- A banana duct-taped to a wall sold for $6.2 million at a Sotheby’s art auction USA TODAY

- Is this banana duct-taped to a wall really worth $6.2 million US? Somebody thought so CBC.ca

Art

Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas on mixing Haida art with Japanese manga – CBC.ca

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas on mixing Haida art with Japanese manga CBC.ca

Source link

Art

Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

- Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York BBC.com

- A duct-taped banana sells for $6.2 million at an art auction NPR

- Is this banana duct-taped to a wall really worth $6.2 million US? Somebody thought so CBC.ca

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoEstate sale Emily Carr painting bought for US$50 nets C$290,000 at Toronto auction

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoClass action lawsuit on AI-related discrimination reaches final settlement

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoCanada’s Hadwin enters RSM Classic to try new swing before end of PGA Tour season

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoAll premiers aligned on push for Canada to have bilateral trade deal with U.S.: Ford

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoTrump nominates former congressman Pete Hoekstra as ambassador to Canada

-

News20 hours ago

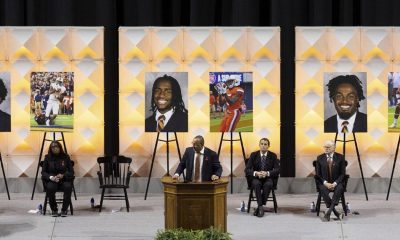

News20 hours agoEx-student pleads guilty to fatally shooting 3 University of Virginia football players in 2022

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoFormer PM Stephen Harper appointed to oversee Alberta’s $160B AIMCo fund manager

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoComcast to spin off cable networks that were once the entertainment giant’s star performers