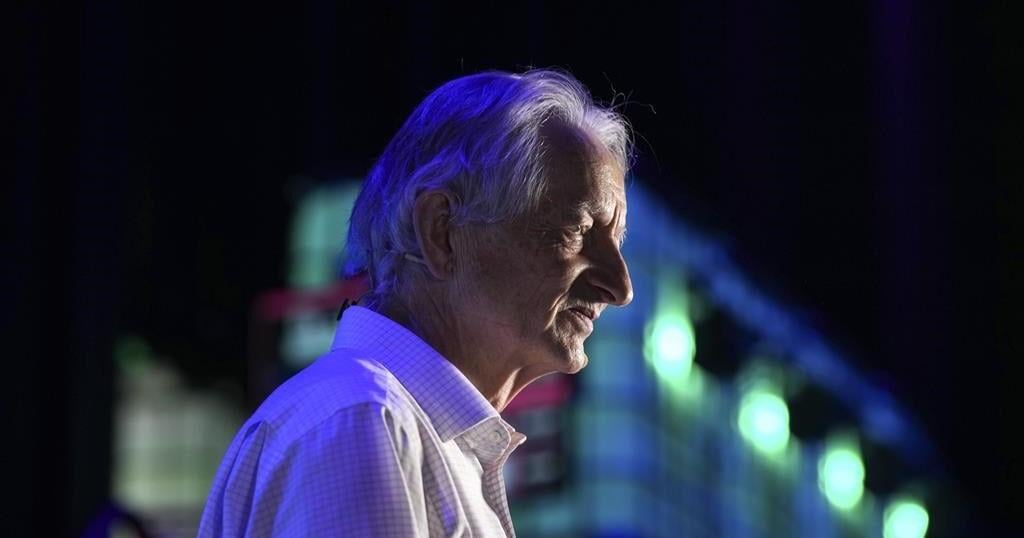

Geoffrey Hinton, the British-Canadian computer scientist whose machine learning discoveries have proved so profound he’s known as the ‘godfather of AI,’ has won the Nobel Prize in physics.

The honour was bestowed Tuesday on Hinton, 76, and Princeton University researcher John Hopfield, 91, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. It chose to award the pair because their use of physics had uncovered patterns in information that laid the foundation for machine learning and neural networks.

Machine learning is a form of computer science that relies on data and algorithms to help artificial intelligence mimic how humans learn, while neural networks are models that emulate the human brain by learning from data and detecting patterns. Both technologies underpin artificial intelligence, which provides the framework for devices and systems used across every industry around the world.

During a Stockholm news conference to announce the award, Hinton said he was “flabbergasted” when the academy reached him by phone to announce his prize.

“I had no idea this would happen. I am very surprised,” he said.

He later told an interviewer from the Nobel Prize that he had learned of his win around 2 a.m., while at a “cheap” hotel in California, where he was due to receive an MRI on Tuesday.

“I guess I’ll have to cancel that,” he joked.

When the call came in from Stockholm, Hinton doubted it was even real.

“My very first thought was how could I be sure it wasn’t a spoof call?” he said.

He was convinced of its authenticity when he realized it was coming from Sweden: “The person had a strong Swedish accent and there were several of them.”

His win will hand him half the share of the 11 million Swedish kronor (about C$1.45 million) from a bequest left by the award’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, but it will also further cement Hinton’s status as an AI pioneer.

While the technology has deeply fascinated the computer scientist for decades, he’s more recently developed concerns about AI because it has become even more advanced and accessible than he once imagined.

Since the November 2022 release of AI chatbot ChatGPT, everyone from students looking to cut corners on homework to tech giants wanting to boost profits have been racing to innovate with machine learning. Regulators have thus been left to figure out how to curtail some of the technology’s risks.

Despite AI’s recent explosion on the tech scene, Hinton has been researching the technology since the 1980s.

When co-laureate Hopfield created an associative memory that can store and reconstruct images in data, Hinton uncovered a way to find properties in data and identify specific elements in pictures, said the University of Toronto, where Hinton is a professor emeritus, Tuesday.

Hinton and his graduate students later built on the Boltzmann machine, which can classify images and generate new examples of patterns it was trained on, ushering in a modern take on machine leaning.

Their work has ultimately “become part of our daily lives, for instance in facial recognition and language translation,” Ellen Moons, chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said.

Much of Hinton’s work was completed at U of T’s computer science department, where he became a professor in 1987. He left about a decade later to found a computational neuroscience unit at University College London but returned in 2001.

In 2012, his team at the University of Toronto won the prestigious ImageNet computer vision competition by developing a technique that could identify images far better than competitors.

A year later, Google acquired DNNresearch, Hinton’s neural networks startup based on his U of T research.

In 2018, an even bigger honour came his way in the form of the A.M. Turing Award, known as the Nobel Prize of computing, which he won with fellow Canadian Yoshua Bengio and American Yan LeCun.

After learning of the Nobel announcement, Bengio said he emailed his congratulations to Hinton, who he said responded “warmly.”

Bengio was a grad student when Hopfield and Hinton made several of their breakthroughs in the eighties.

“It changed really the meaning of AI for me and it made me really excited about working on neural networks because it not only brought concepts from physics into AI, which is really cool, but it also brought a broader, maybe more important idea,” Bengio recalled.

“In the same way that in physics, we are able to explain what is going on with a few simple mathematical equations, we could do the same to understand intelligence … and that was not at all a common view.”

The pair later met when Bengio became a professor. Hinton exceeded his expectations.

“He’s the kind of person who has a new idea a day,” Bengio said. “Very creative, very insightful, but also a real scholar (because) he’s interested in everything.”

Lately, much of Hinton’s interest lies in worries about the technology that has been his life’s work. He quit his role as vice-president and engineering fellow at Google last spring so he could speak more freely about the risks of AI.

The move made Hinton a hot commodity on the tech conference circuit, where he has told audiences in Toronto that he fears AI could trigger lethal autonomous weapons, discrimination, unemployment, misinformation and even the demise of humanity.

Despite urging the world to act quickly to prevent the worst scenarios it could cause, he hasn’t eschewed AI completely.

“Whenever I want to know the answer to anything, I just go and ask GPT4,” Hinton said at the Nobel announcement, referring to the chatbot’s latest model.

“I don’t totally trust it, because it can hallucinate, but on almost everything, it’s a not very good expert.”

Ilya Sutskever, the co-founder of ChatGPT-maker OpenAI, was one of the students Hinton won the ImageNet prize with.

Other proteges including Aidan Gomez and Nick Frosst have gone on to found Cohere, one of the country’s buzziest AI startups. Gomez called Hinton “a real hero for our field and for Canada” and Frosst said “his passion for discovery and invention will always be an inspiration but his kindness, playfulness and mentorship have benefitted me most.”

Hinton’s influence on burgeoning tech talent has largely come from his close ties to U of T but also his work as a chief scientific adviser at the Vector Institute in Toronto and his investment in Radical Ventures, a Toronto-based venture capital fund focused on AI.

In congratulating Hinton, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland called him “the teacher of generations of great Canadian intellectual leaders,” while U of T president Meric Gertler said the school was “immensely proud of his historic accomplishment.”

Tony Gaffney, Vector’s president and CEO, said Hinton’s “pioneering research at the University of Toronto not only revolutionized the field of AI but has also been instrumental in establishing Canada as a global powerhouse in AI research and innovation.”

— With files from Craig Wong and Dylan Robertson in Ottawa and Jordan Omstead in Toronto

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 8, 2024.