The Pantone colour system is used for matching shades of colour.

Brent Rose / Global News

|

|

Stepping into Stuart Semple’s world is like entering a Willy Wonka-esque fantasyland. Only instead of chocolate and candy, everywhere you look there are bags of bright powdered paint pigments, colour-mixing machines, paint-spattered canvases, sculptures, brushes and of course, brightly coloured bottles of paint.

The man himself bustles around with a giddy sort of energy, clad in furry animal slippers, with long hair and perpetually paint-stained fingers, a visual reminder of his love affair with colour.

“I would explain colour as something that can change our emotions and our state and way of being as we interact with that. And it is a way, really, of feeling the world inside us visually.”

To see him, you’d never think Semple is anything other than a creative type. You certainly wouldn’t peg him as a political crusader. But when someone threatens what he sees as a universal right to artistic self-expression, a different picture emerges.

Sitting in his studio on England’s south coast, Semple is looking at a popup message on his computer screen, brow furrowed.

“Some Pantone colours may no longer be available due to changes in Pantone’s licensing with Adobe.”

In November, creators saw a similar message pop up in their Adobe software, meaning colours they’d previously been able to access were no longer available. Adobe is the industry standard for digital artists all over the world, and Pantone supplies many of the digital colour palettes.

Semple immediately saw red.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I think they’re (Pantone) just trying to milk the creators that use their tools for more money.”

Pantone’s palettes are the international language of colour. The company’s colour coding system is nearly universally used to match shades and allow printers to accurately reproduce computerized artwork across the globe. But all of a sudden, many of the colours artists rely on were jailed behind an additional paywall.

“I think that there’s a difference between being a business and being commercially minded and paying your staff and keeping the lights on, to actually just seeing how much you can squeeze out of people, and it feels like that’s what they’re doing.”

Semple’s reverence for colour and art goes back to his childhood. He grew up in a modest, working-class family. A high achiever in school, he was destined for a high-paying career as a doctor or lawyer. But a trip to the National Gallery in London when he was eight years old lit a creative fire.

“I came in contact with Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and it made a huge impact on my whole life and it sort of burned into my head,” he says.

“And my mum said I was in a state of almost awe, like I was shaking in front of this thing.”

The young Semple got home and immediately started creating. He couldn’t afford professional paints, so he made them himself with household materials.

“We didn’t have art materials. I mean, that was a luxury. So I started, like most kids do, going into the kitchen and mixing food colouring with, you know, beetroot and cooking oil and making these colours and slapping them on things.”

Today, Semple is a successful artist, and he hasn’t lost his passion for producing pigment. He still makes his own shades of paint. Mixing up an extremely bright shade of pink — he calls it the Pinkest Pink — the childlike wonder is still there.

“Aww! There’s something so satisfying about it,” he giggles, dumping in the powdered paint pigment and watching it swirl around the mixer.

He knows the science, obsessing over details to make his paints pop.

“By using resins that can hold a lot of ingredients, you can put a lot more ingredients in, which means you can actually put more pigment in,” he says. “And it’s all to do with the shape of the pigment because a spherical shape will reflect light in a very direct angle from one small bit of surface area, whereas a flatter pigment will do the opposite.”

But there’s something much larger at play here. What makes Semple’s studio truly special is the philosophy behind the operation. Art is an expensive endeavour, often only open to the wealthy. Semple’s own experience is one factor that drives him to help make art affordable to both patrons and creators. He makes high-quality paints he sells at reasonable prices.

“So it’s more than, how do I make money? It’s actually more, how do I make art accessible and give people, you know, the chance to interact with it?”

That’s just one part of the operation. Semple employs 20 people, all of whom are artists. He gives them free access to materials, studio space, tools and mentorship to support them to create their own works of art. Semple also founded the “Giant” art gallery in his hometown of Bournemouth, which offers free admission, and the online VOMA gallery (Virtual Online Museum of Art). Just as he believes art should be for everyone, he says that the colours all around us should be free to enjoy and inspire creativity.

That’s what made him so mad about Adobe and Pantone restricting access to colours that had been free for years.

“We all consume colour all day long, so we’re all invested in it,” Semple says. “So it actually does really, really matter. And as these corporations get big and become mega-corporations, the idea that we have a culture that is being dominated by the richest and most powerful and they can actually control the colours that we see is outrageous.”

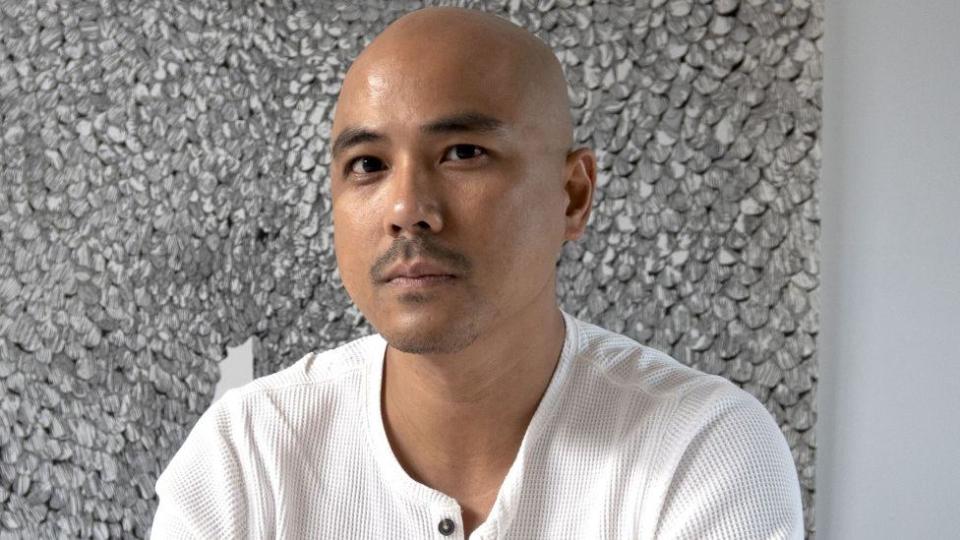

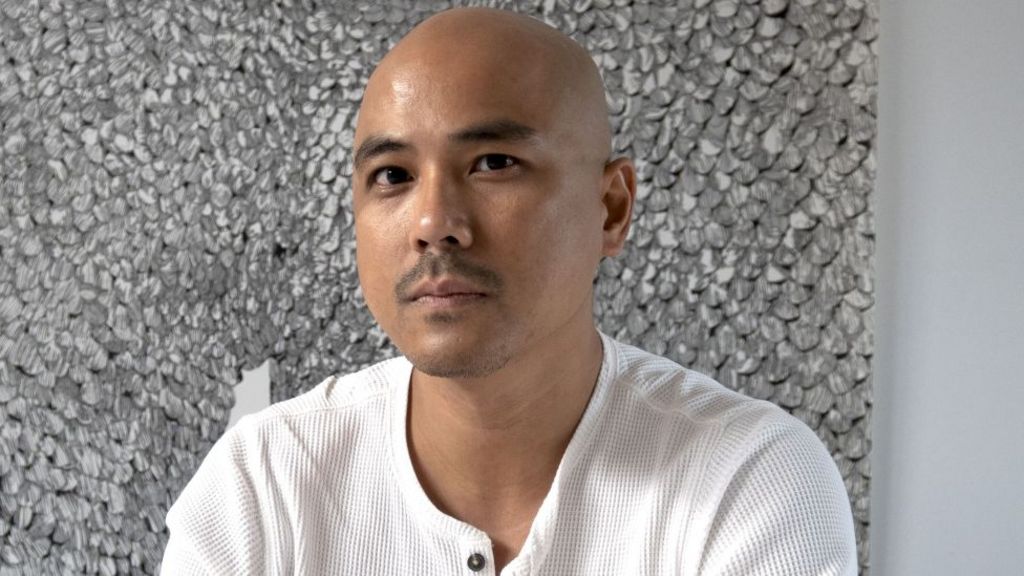

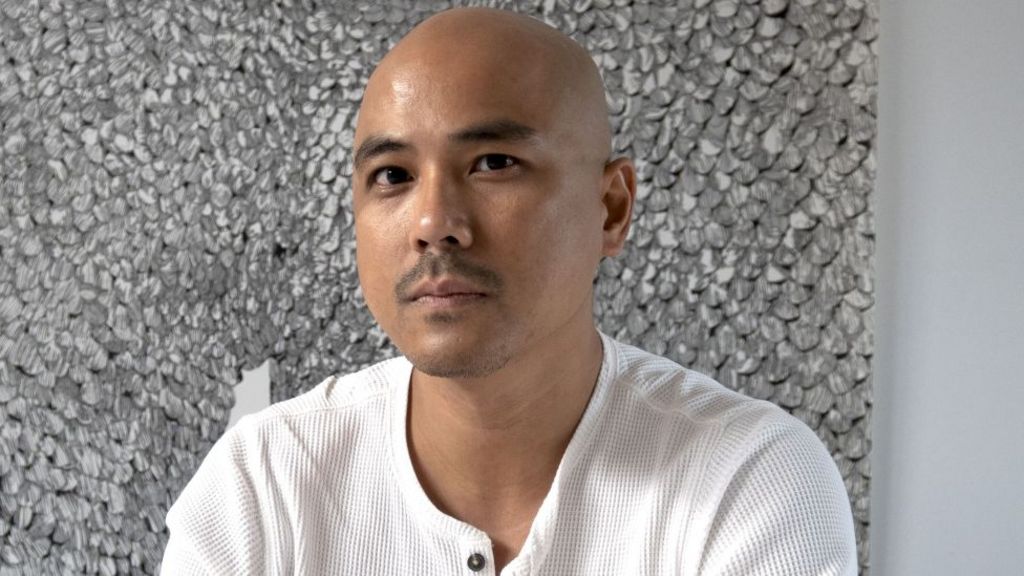

Across the Atlantic ocean in Toronto, graphic artist Daryl Woods got the same message Adobe users everywhere were seeing: if he wanted access to the same range of Pantone colours he’d had for years, he’d have to pay extra, over and above the $80 per month he already pays for his Adobe software subscription.

“I think this is pretty much a cash grab by Pantone. This is something that’s been available for probably a couple of decades at least,” Woods says.

Woods has a graphic design business, creating art for advertisements and for packaging on brands, like wine labels. And he says most digital artists rely on Adobe software and Pantone’s colour palettes.

“I can’t do my work without the Adobe products. They are just part of my everyday life. And I think that pretty much goes for anybody who works in visual communication.”

Semple decided to do something about the new fee. In just a few hours, he created a software plug-in for Adobe that had colour palettes that he describes as “indistinguishable” from Pantone’s. He calls his “Sempletones.”

“One of the things that people don’t know is that I learned how to program a computer when I was eight,” he says casually. “So coding and computers are a huge part of my life. And yeah, I can do things like that.”

So why did he do it?

“I hate the idea that art or colour or materials are sort of gate-kept, in any way, shape or form,” Semple says. “I really think it’s important that people have that permission to kind of do their thing with the stuff they need to do it.”

Woods was impressed Semple was able to come up with a workaround so quickly. “I was very surprised at how easy it was to work with how complete it was. It’s no different than when I used Pantone colours.”

Global News reached out to Adobe and Pantone for comment. Adobe responded that it was Pantone’s decision to charge an additional fee to access its complete range of colours, and that “the Adobe team continues to find ways to lessen the impact on our customers.”

Pantone did not directly address the question of who was responsible for pulling some of its colour palettes, but the company is now selling a separate plug-in with the missing colours directly on its website at a cost of $19.99 per month or $119.99 per year.

For Semple, the Adobe-Pantone affair was just the latest battle in a long-running colour crusade.

In 2016, he got into a very public feud with Anish Kapoor. He’s the British artist perhaps best known for “Cloud Gate,” sometimes better known as “The Bean,” a public art installation at Chicago’s Millennium Park.

In 2016, Kapoor bought the exclusive artistic rights to Vantablack, a material then known as the world’s blackest black. Vantablack absorbs 99.965 per cent of visible light, creating the impression of complete dark, flatness.

Semple criticized Kapoor for keeping the material for himself, and in response, decided to sell a special shade he made called “The Pinkest Pink.” He made it available for purchase on his website, with one caveat: “By adding this product to your cart you confirm that you are not Anish Kapoor, you are in no way affiliated to Anish Kapoor, you are not purchasing this item on behalf of Anish Kapoor or an associate of Anish Kapoor. To the best of your knowledge, information and belief this paint will not make its way into the hands of Anish Kapoor.”

Semple’s efforts to keep colour accessible during the Adobe/Pantone episode, as well as his response to Kapoor’s attempts to keep Vantablack for himself, have earned him comparisons to Robin Hood.

“People say that. It’s a weird thing,” Semple says self-consciously, before adding: “Maybe it’s just a weird, geeky thing that only I’m interested in, which is why no one’s doing it. But I really enjoy doing it. It’s something I love to do.”

Kapoor’s response was, perhaps, a little less than collegial. He posted a simple, terse retort on his Instagram, a middle finger, dipped in Semple’s pink paint.

But that episode wasn’t just a petty slap fight between two rivals within the narrow confines of the art world. Just as charging Adobe users extra to access some of Pantone’s range of colours wasn’t just a small extra charge. It’s all part of a larger trend to commodify colour.

In 2019, Canada’s trademark laws were updated to allow businesses to trademark colours closely associated with their brands. Tiffany & Co, the jeweller known for its iconic robin’s egg blue box, is often cited as an example.

“So historically, you could claim a Tiffany blue box,” says Toronto intellectual property lawyer Sebastian Beck-Watt. “So you would say the colour blue, as applied to the surface of a box. And then you would say, I’m claiming this trademark in association with jewellery, for example.”

But in 2019, Canada followed other countries and updated its trademark law, allowing brands to trademark colour “per se.” That allows businesses to trademark shades associated with their brand across a more general range of products and services they offer, and stop industry competitors from using similar hues.

TD Bank has applied for the trademark for the green colour associated with its brand, Pantone 361. TD lists a range of products and services, and nobody knows how far companies might go to protect a colour trademark. But we have a hint from other countries.

In 2019, the parent company of mobile giant T-Mobile sued Lemonade, a small insurance company which had just launched in Germany. The parent company, Deutsche Telekom, claimed Lemonade used a shade of pink that was too close to its familiar magenta, or Pantone Rhodamine Red U, and that its trademark over similar shades extended to Lemonade’s insurance business. European countries have allowed businesses to trademark colours before Canada, and Lemonade was forced to remove the pink from its branding in Germany.

In 2020, however, Lemonade won a court challenge in France, when a court ruled “there is no evidence of genuine use of this mark for the contested services.” But the case provides a cautionary tale, because it shows large corporations can drag smaller parties through costly court proceedings, even when they don’t have a valid claim.

It is also illustrative of the subjectivity of colour. How will courts determine when two shades of the same colour are too close to tell the difference? Beck-Watt says there’s no way of knowing how far it will go until the laws are tested in court.

“Something like colour might be an instance where you take a survey of the public and see how close they think these are.”

Determining matters of law so subjectively raises another issue: people’s brains do not process colour in the same way.

“I’m colour blind,” Semple says, without a hint of irony.

Really?

“Yeah, actually. Colour blind. Blue and purple. Which is a rare one.”

In spite of his inability to distinguish between some colours, Semple is fearless in his opposition to any attempt to control and restrict them. Tiffany has had a trademark for Pantone 1837 in the US since 1998. Semple responded by creating “Tiff,” a very similar shade of blue.

It all makes his lawyers nervous.

“They always say the same thing, which is that what I’m doing is risky. And I should be aware of that, you know.” But he has no intention of stopping

It could be called a principled stand, or perhaps brazen, almost reckless. But for Semple, it’s worth it. Art, he says, saved his life when he was in his late teens, when a sandwich triggered a severe allergic reaction and landed him in hospital.

“I kind of died for a few seconds, in the middle of the night. And I said goodbye to my mom and my sister, and my nana had been in. My whole body went into hives and I completely flatlined and kind of died for a bit. And then I came back and everything was different after.”

Art, he says, became a way of coping with the reality that everything could be taken away at any moment.

“It changed everything. So the first thing that happened, which is a bit of a cliche and a bit weird to say, is that I decided I wanted to be an artist. I was like, ‘If I live, I’m going to make art every day, all day.’”

That’s a big reason why Semple is so steadfast in his efforts to stop anyone from trying to “own” or restrict colours.

“No one can own colour,” he says pointedly. “Colour exists. It’s just a phenomenon of nature. How can you own an experience that your eyes have when they see something?”

There is a sour tendency in cultural politics today — a growing gap between speaking about the world and acting in it.

In the domain of rhetoric, everyone has grown gifted at pulling back the curtain. An elegant museum gallery is actually a record of imperial violence; a symphony orchestra is a site of elitism and exploitation: these critiques we can now deliver without trying. But when it comes to making anything new, we are gripped by near-total inertia. We are losing faith with so many institutions of culture and society — the museum, the market, and, especially this week, the university — but cannot imagine an exit from them. We throw bricks with abandon, we lay them with difficulty, if at all. We engage in perpetual protest, but seem unable to channel it into anything concrete.

So we spin around. We circle. And, maybe, we start going backward.

I’ve just spent a week tramping across Venice, a city of more than 250 churches, and where did I encounter the most doctrinaire catechism? It was in the galleries of the 2024 Venice Biennale, still the world’s principal appointment to discover new art, whose current edition is at best a missed opportunity, and at worst something like a tragedy.

It’s often preachy, but that’s not its biggest problem. The real problem is how it tokenizes, essentializes, minimizes and pigeonholes talented artists — and there are many here, among more than 300 participants — who have had their work sanded down to slogans and lessons so clear they could fit in a curator’s screenshot. This is a Biennale that speaks the language of assurance, but is actually soaked in anxiety, and too often resorts, as the Nigerian author Wole Soyinka deplored in a poem, to “cast the sanctimonious stone / And leave frail beauty shredded in the square / Of public shame.”

This year’s Biennale opened last week under an ominous star. The Venetian megashow consists of a central exhibition, spanning two locations, as well as around 90 independent pavilions organized by individual nations. One of these nations is Israel, and in the weeks before the vernissage an activist group calling itself the “Art Not Genocide Alliance” had petitioned the show’s organizers to exclude Israel from participating. The Biennale refused; a smaller appeal against the pavilion of Iran also went nowhere. (As for Russia, it remains nation non grata for the second Biennale in a row.) With disagreements over the war in Gaza spilling into cultural institutions across the continent — they’d already sunk Documenta, the German exhibition that is Venice’s only rival for attendance and prestige — the promise of a major controversy seemed to hang over the Giardini della Biennale.

As it happened, the artist and curator of Israel’s pavilion surprised the preview audience by closing their own show, and posted a sign at the entrance declaring it would stay shut until “a cease-fire and hostage release agreement is reached.” A small protest took place anyway (“No Death in Venice” was one slogan), but the controversy had only a tiny impact on the Prosecco-soaked Venetian carnival that is opening week. Right next door, at the U.S. Pavilion, twice as many visitors were waiting to get inside as were protesting.

One could strain to read the Israeli withdrawal productively, as part of a century-long tradition of empty, vacated or closed exhibitions by artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija, Graciela Carnevale, and all the way back to Marcel Duchamp. Probably it was the only possible response to an untenable situation. Either way, the Israel pavilion encapsulated in miniature a larger dilemma and deficiency, in Venice and in culture more broadly: a thoroughgoing inability — even Foucault did not go this far! — to think about art, or indeed life, as anything other than a reflection of political, social or economic power.

That is certainly the agenda of the central exhibition, organized by the Brazilian museum director Adriano Pedrosa. I’d cheered when he was appointed curator of this year’s edition. At the São Paulo Museum of Art, one of Latin America’s boldest cultural institutions, Pedrosa had masterminded a cycle of centuries-spanning exhibitions that reframed Brazilian art as a crucible of African, Indigenous, European and pan-American history. His nomination came a few weeks after Giorgia Meloni became Italy’s first far-right prime minister since World War II. And Pedrosa — who had successfully steered his museum through Brazil’s own far-right presidency of 2018-22 — promised a show of cosmopolitanism and variety, as expressed in a title, “Foreigners Everywhere,” that seemed like a moderate anti-Meloni dig.

But what Pedrosa has actually brought to Venice is a closed, controlled, and at times belittling showcase, which smooths out all the distinctions and contradictions of a global commons. The show is remarkably placid, especially in the Giardini. There are large doses of figurative painting and (as customary these days) weaving and tapestry arranged in polite, symmetrical arrays. There is art of great beauty and power, such as three cosmological panoramas by the self-taught Amazonian painter Santiago Yahuarcani, and also far less sophisticated work celebrated by the curator in the exact same way.

In the brutal rounding-down arithmetic of the 2024 Venice Biennale, to be a straniero — a “foreigner” or “stranger,” applied equally to graduates of the world’s most prestigious M.F.A. programs and the mentally ill — implies moral credibility, and moral credibility equals artistic importance. Hence Pedrosa’s inclusion of L.G.B.T.Q. people as “foreigners,” as if gender or sexuality were proof of progressive bona fides. (Gay men have led far-right parties in the Netherlands and Austria; over at Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection is a wonderfully pervy show of the polymathic Frenchman Jean Cocteau, who praised Nazis while drawing sailors without their bell-bottoms.)

Even more bizarre is the designation of the Indigenous peoples of Brazil and Mexico, of Australia and New Zealand, as “foreigners”; surely they should be the one class of people exempt from such estrangement. In some galleries, categories and classifications take precedence over formal sophistication to a derogatory degree. The Pakistan-born artist Salman Toor, who paints ambiguous scenes of queer New York with real acuity and invention, is shown alongside simplistic queer-and-trans-friendly street art from an Indian NGO “spreading positivity and hope to their communities.”

Over and over, the human complexity of artists gets upstaged by their designation as group members, and art itself gets reduced to a symptom or a triviality. I felt that particularly in three large, shocking galleries in the central pavilion of the Giardini, packed tight with more than 100 paintings and sculptures made in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East between 1915 and 1990. These constitute the bulk of what Pedrosa calls the show’s nucleo storico, its historical core, and this was the part of the Biennale I’d looked forward to most. It had promised to demonstrate that the world outside the North Atlantic has a history of modern art far richer than our leading museums have shown us.

Indeed it does. But you won’t learn that here, where paintings of wildly different importance and quality have been shoved together with almost no historical documentation, cultural context, or even visual delight. It flushes away distinctions between free and unfree regimes or between capitalist and socialist societies, or between those who joined an international avant-garde and those who saw art as a nationalist calling. True pioneers, such as the immense Brazilian innovator Tarsila do Amaral, are equated with orthodox or traditionalist portraitists. More ambitious exhibitions — notably the giant “Postwar,” staged in Munich in 2016-17 — used critical juxtaposition and historical documentation to show how and why an Asian modernism, or an African modernism, looked the way it did. Here in Venice, Pedrosa treats paintings from all over as just so many postage stamps, pasted down with little visual acuity, celebrated merely for their rarity to an implied “Western” viewer.

You thought we were all equals? Here you have the logic of the old-style ethnological museum, transposed from the colonial exposition to the Google Images results page. S.H. Raza of India, Saloua Raouda Choucair of Lebanon, the Cuban American Carmen Herrera, and also painters who were new to me, got reduced to so much Global South wallpaper, and were photographed by visitors accordingly. All of which shows that it’s far too easy to speak art’s exculpatory language, to invoke “opacity” or “fugitivity” or whatever today’s decolonial shibboleth may be. But by othering some 95 percent of humanity — by designating just about everyone on earth as “foreigners,” and affixing categories onto them with sticky-backed labels — what you really do is exactly what those dreadful Europeans did before you: you exoticize.

And yet, for all that, there is so much I liked in this year’s Biennale! From the central exhibition I am still thinking about a monumental installation of unfired coils of clay by Anna Maria Maiolino, a winner of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, that recasts serial production as something intimate, irregular, even anatomical. Karimah Ashadu, who won the Silver Lion for her high-speed film of young men bombing across Lagos on banned motorbikes, gave the economic intensity of megacity life a vigorous visual language. There are the stark, speechless paintings from the 1970s of Romany Eveleigh, whose thousands of scratched little O’s turn writing into an unsemantic howl. There are Yuko Mohri’s mischievously articulated assemblages of found objects, plastic sheeting and fresh fruit, in the Japanese Pavilion, and Precious Okoyomon’s Gesamtkunstwerk of soil, speakers and motion sensors, in the Nigerian Pavilion.

Beyond the Biennale, Christoph Büchel’s frenzied exhibition at the Fondazione Prada assembles mountains of junk and jewels into an impertinent exposé of wealth and debt, colonialism and collecting. In the Palazzo Contarini Polignac, a hazily elegant video by the Odesa-born artist Nikolay Karabinovych reinscribes the Ukrainian landscape as a crossroads of languages, religions and histories. Above all there is Pierre Huyghe, at the Punta della Dogana, who fuses human intelligence and artificial intelligence into the rarest thing of all: an image we have never seen before.

What all these artists have in common is some creative surplus that cannot be exploited — not for a nation’s image, not for a curator’s thesis, not for a collector’s vanity. Rather than the sudsy “politics” of advocacy, they profess that art’s true political value lies in how it exceeds rhetorical function or financial value, and thereby points to human freedom. They are the ones who offered me at least a glimpse of what an equitable global cultural assembly could be: an “anti-museum,” in the phrase of the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, where “the exhibiting of subjugated or humiliated humanities” at last becomes a venue where everyone gets to be more than a representative.

I still, unfashionably, keep faith with Mbembe’s dream institution, and the artists here who would have their place in it. But we won’t build it with buzzwords alone, and if anyone had actually been paying attention to the political discourse in this part of the world in a time of war, they would have realized that two can play this game. “An essentially emancipatory, anticolonial movement against unipolar hegemony is taking shape in the most diverse countries and societies” — did someone in the 2024 Venice Biennale say that? No, it was Vladimir Putin.

|

|

A Scottish artist who uses cars, worship bells and Irn-Bru in her work is among the nominees for this year’s Turner Prize.

Glasgow-born Jasleen Kaur’s work reflects her life growing up in the city’s Sikh community.

She is up for the prestigious art award, now in its 40th year, alongside Pio Abad, Claudette Johnson and Delaine Le Bas.

Turner Prize jury chairman Alex Farquharson described it as a “fantastic shortlist of artists”

Works by the nominated artists will go on show at London’s Tate Britain gallery from 25 September.

They will receive £10,000 each, while the winner, to be announced on 3 December, will get £25,000.

In a statement, Farquharson said: “All four make work that is full of life.

“They show how contemporary art can fascinate, surprise and move us, and how it can speak powerfully of complex identities and memories, often through the subtlest of details.

“In the Turner Prize’s 40th year, this shortlist proves that British artistic talent is as rich and vibrant as ever.”

The shortlisted artists are:

Manila-born Abad’s solo exhibition To Those Sitting in Darkness at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford included drawings, etchings and sculptures that combined to “ask questions of museums”, according to the jury.

The 40-year-old, who works in London, reflects on colonial history and growing up in the Philippines, where his parents struggled against authoritarianism.

The title of his exhibit is a nod to Mark Twain’s 1901 essay To the Person Sitting In Darkness, which hit out at imperialism.

Kaur is on the list for Alter Altar at Tramway, Glasgow, which included family photos, an Axminster carpet, a classic Ford Escort covered in a giant doily, Irn-Bru and kinetic handbells.

The 37-year-old, who lives in London, had previously showcased her work at the Victoria and Albert Museum by looking at popular Indian cinema.

Worthing-born Le Bas is nominated for an exhibition titled Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life/A New Life Is Beginning. Staged at the Secession art institute in Vienna, Austria, it saw painted fabrics hung, with theatrical costumes and sculptures also part of the exhibit.

The 58-year-old artist was inspired by the death of her grandmother and the history of the Roma people.

The jury said they “were impressed by the energy and immediacy present in this exhibition, and its powerful expression of making art in a time of chaos”.

Manchester-born Johnson has been given the nod for her solo exhibition Presence at the Courtauld Gallery in London, and Drawn Out at Ortuzar Projects, New York.

She uses portraits of black women and men in a combination of pastels, gouache and watercolour, and was praised by the judges for her “sensitive and dramatic use of line, colour, space and scale to express empathy and intimacy with her subjects”.

Johnson, 65, was appointed an MBE in 2022 after being named on the New Year Honours list for her services to the arts.

|

|

A Scottish artist who uses cars, worship bells and Irn-Bru in her work is among the nominees for this year’s Turner Prize.

Glasgow-born Jasleen Kaur’s work reflects her life growing up in the city’s Sikh community.

She is up for the prestigious art award, now in its 40th year, alongside Pio Abad, Claudette Johnson and Delaine Le Bas.

Turner Prize jury chairman Alex Farquharson described it as a “fantastic shortlist of artists”

Works by the nominated artists will go on show at London’s Tate Britain gallery from 25 September.

They will receive £10,000 each, while the winner, to be announced on 3 December, will get £25,000.

In a statement, Farquharson said: “All four make work that is full of life.

“They show how contemporary art can fascinate, surprise and move us, and how it can speak powerfully of complex identities and memories, often through the subtlest of details.

“In the Turner Prize’s 40th year, this shortlist proves that British artistic talent is as rich and vibrant as ever.”

The shortlisted artists are:

Manila-born Abad’s solo exhibition To Those Sitting in Darkness at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford included drawings, etchings and sculptures that combined to “ask questions of museums”, according to the jury.

The 40-year-old, who works in London, reflects on colonial history and growing up in the Philippines, where his parents struggled against authoritarianism.

The title of his exhibit is a nod to Mark Twain’s 1901 essay To the Person Sitting In Darkness, which hit out at imperialism.

Kaur is on the list for Alter Altar at Tramway, Glasgow, which included family photos, an Axminster carpet, a classic Ford Escort covered in a giant doily, Irn-Bru and kinetic handbells.

The 37-year-old, who lives in London, had previously showcased her work at the Victoria and Albert Museum by looking at popular Indian cinema.

Worthing-born Le Bas is nominated for an exhibition titled Incipit Vita Nova. Here Begins The New Life/A New Life Is Beginning. Staged at the Secession art institute in Vienna, Austria, it saw painted fabrics hung, with theatrical costumes and sculptures also part of the exhibit.

The 58-year-old artist was inspired by the death of her grandmother and the history of the Roma people.

The jury said they “were impressed by the energy and immediacy present in this exhibition, and its powerful expression of making art in a time of chaos”.

Manchester-born Johnson has been given the nod for her solo exhibition Presence at the Courtauld Gallery in London, and Drawn Out at Ortuzar Projects, New York.

She uses portraits of black women and men in a combination of pastels, gouache and watercolour, and was praised by the judges for her “sensitive and dramatic use of line, colour, space and scale to express empathy and intimacy with her subjects”.

Johnson, 65, was appointed an MBE in 2022 after being named on the New Year Honours list for her services to the arts.

Opinion: Fear the politicization of pensions, no matter the politician

NASA Celebrates As 1977’s Voyager 1 Phones Home At Last

Pecker’s Trump Trial Testimony Is a Lesson in Power Politics

B.C. online harms bill on hold after deal with social media firms

B.C. puts online harms bill on hold after agreement with social media companies

Oil Firms Doubtful Trans Mountain Pipeline Will Start Full Service by May 1st

Trump poised to clinch US$1.3-billion social media company stock award

Turner Prize: Shortlisted artist showcases Scottish Sikh community