TORONTO —

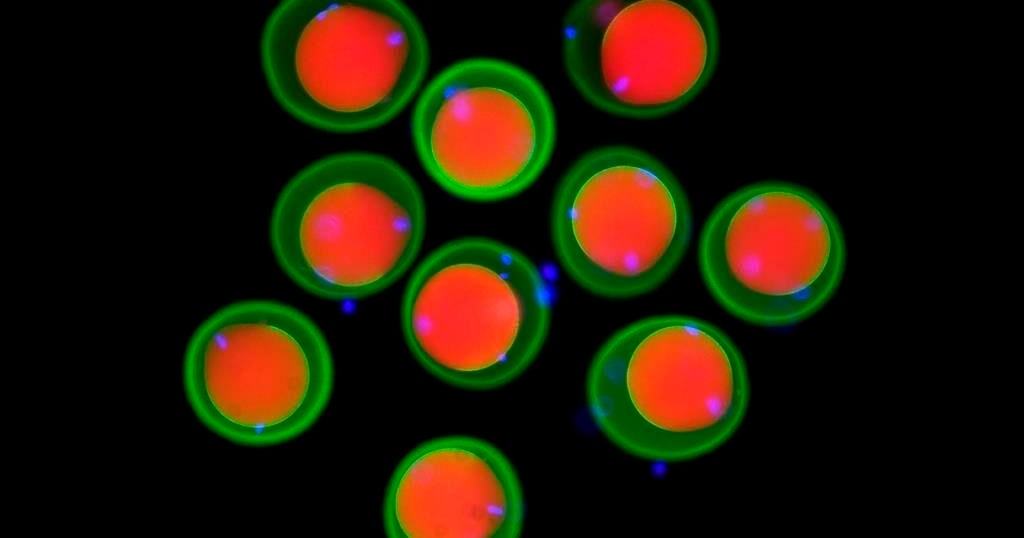

A new study looking at how long the novel coronavirus can survive on surfaces found that it can remain infectious on some surfaces — including bank notes — for at least 28 days, provided the temperature is right.

Published this week in the Virology Journal, the new paper describes how researchers tested the virus on several surfaces, including cotton and bank notes, at numerous temperatures in order to measure the lifespan of the virus under these different circumstances.

They found that the virus dies significantly faster on surfaces in hotter temperatures, and can survive on several non-porous surfaces for up to four weeks — much longer than previous studies have indicated.

Overwhelmingly, evidence has shown that the primary way COVID-19 is spread is through droplets and through sharing air with others, but that hasn’t stopped the fear of surface transmission. Hand washing is still one of the most important prevention methods that health officials tout.

Previous studies have looked at how long SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, remains infectious on different surfaces, with some studies finding it to be a matter of hours, and others saying it could be days.

In this study, the surfaces researchers tested the virus on included Australian bank notes — which, like Canadian bank notes, are polymer — paper bank notes, glass, vinyl, stainless steel and cotton.

Researchers noted that they wanted to include money because it is an object that travels frequently between different people. Stainless steel, vinyl and glass are materials found in most public spaces, and cotton is often found in clothing and bedding.

When a virus gets onto a surface, it is often through a sneeze or through droplets expelled from the mouth. Researchers diluted SARS-CoV-2 “in a defined organic matrix […] designed to mimic the composition of body secretions” before placing it onto the materials to measure the longevity.

They noted in the paper that the concentration of the virus in each sample was high, it still “represents a plausible amount of virus that may be deposited on a surface.”

Samples of each material with the virus on it were placed into a “humidified climate chamber” so a set humidity of 50 per cent relative humidity could be maintained while the samples were tested at different temperatures and timeframes.

Samples were tested at 20, 30 and 40 degrees Celsius, and were inspected 1 hour, 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, 21 days and 28 days after the virus had first been introduced to the material.

Researchers found that at 20 degrees Celsius, the virus could survive for at least 28 days on every material except for cotton, the most porous of the materials tested.

SARS-CoV-2 couldn’t be detected on cotton after 14 days had passed.

“The majority of virus reduction on cotton occurred very soon after application of virus, suggesting an immediate absorption effect,” the report said.

Does this mean every bank note in our wallets could infect us? According to Colin Furness, an infection control epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, we shouldn’t jump straight to alarm.

“What we’re seeing empirically, clinically, with contact tracing, is that COVID is not spreading heavily through touch,” he said.

It is possible to contract the virus through surfaces, he said, “but it’s not happening very often.”

He said that earlier in the pandemic, when we had a looser understanding of the virus, there was a bigger fear of things like groceries or the mail in terms of surface transmission. But at this point, we have a greater understanding of how COVID-19 predominantly spreads.

“It’s shared airspace,” Furness said. “It’s droplet and aerosols and shared air with poor ventilation and prolonged contact. That’s how you get sick. That’s the thing to be scared of, which is why I’ve been very, very worried about indoor dining. And it’s not because you might touch contaminated cutlery. It’s because you’re in this room with a lot of other people and not wearing a mask and sharing air.”

This study carried out its experiments at a lab at the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness, with the samples in complete darkness “to negate any effects of UV light” — just one way that the conditions of the experiments differed from real life.

“[This study] tells you what can happen under laboratory conditions,” Furness said.

A bank note in your pocket or your wallet is rubbing up against other things, he explained, not sitting undisturbed to measure the longevity of a virus. If surfaces are exposed to sunlight as well, that can aid with a faster decay of any virus on the surface.

These studies are the first step, he said, and then researchers “need to test in the real world. What is the real significance of this?

“And those numbers are usually quite different.”

The raw numbers of the study also don’t paint the full picture. Although the virus was still detectable on most surfaces at the 28 day mark, it reduced in concentration much faster than that.

“Viruses aren’t alive,” Furness said. “They can’t regenerate, they can’t metabolize or protect themselves as soon as they leave your body. As soon as you exhale some virus, the virus starts to die.”

The half-life of the virus (the time it takes for it to reduce by 50 per cent) on a paper bank note at 20 degrees Celsius was 2.74 days, showing the viral load decreases in concentration far faster than the 28 days would suggest. After 9.13 days, 90 per cent of the virus was gone.

On cotton, at 20 degrees Celsius, the half-life was 1.68 days, and it took 5.57 days for a 90 per cent reduction in the virus.

Five to nine days is still a long time for a virus to remain infectious on a surface, although it’s still unknown at what point the viral load would be too small to actually make a person ill.

Researchers said in the paper that the extended half-life in this study compared to others could be down to the controlled conditions that they created for the experiment.

While this study does not mean we should panic about surface transmission, which remains one of the rarer ways to transmit the virus, it does provide insight into how temperature interacts with the virus’ survivability.

Researchers did not measure any of the virus samples at less than 20 degrees Celsius, but they observed how much the rate of virus decline sped up when the temperature increased from 30 to 40 degrees Celsius. Extrapolating backwards from that, they posit that if the temperature dropped significantly from 20 degrees Celsius, the lifespan of the virus on various surfaces could increase.

“This data could therefore provide a reasonable explanation for the outbreaks of COVID-19 surrounding meat processing and cold storage facilities,” they theorize.

Furness said the temperature is a huge factor when it comes to a virus’ survivability.

“In the winter, in freezing temperatures, COVID will last [longer] on surfaces,” he said.

“So if you’re going to a playground in the winter, it can be quite worrisome. I wonder whether we’re going to see that COVID does spread more by touch in the winter. I can’t say that it does, but it’s entirely possible that it will.”

He said the concept of temperature is something that hasn’t been emphasized enough as Canada begins to tackle its second wave.

“It’s not just the numbers are going up,” he said. “Numbers are going up, while temperatures are going down.”

The best thing to do?

“We should continue to wash our hands and be vigilant,” Furness said. “In fact, during COVID, I would say the best outcome of washing your hands is actually so you don’t get any other colds that would make you afraid that maybe you have COVID.”

Source: – CTV News

Source link

Related