Summary

- Many Europeans and Americans believe that their political systems are corrupt.

- This disillusionment, combined with kleptocrats’ increasing use of “strategic corruption” in Europe and elsewhere, destabilises Western politics and damages the transatlantic relationship.

- US President Joe Biden has responded to these challenges by declaring that the fight against corruption is a core national security priority and part of his “foreign policy for the middle class”.

- European policymakers should draw on his approach to anticorruption to help rebuild the Western alliance and address the abuse of entrusted power in their own societies.

- They should set up high-profile, DfID-style national institutions that are charged with tackling corruption and capable of working within an international network.

Introduction

The anticorruption fight and its failures have begun to transform Western politics. Donald Trump won the US presidency in a campaign that decried graft among politicians in Washington, clearing the way for four years of unrepentant self-dealing in the White House and havoc in the transatlantic relationship. Key members of the British government travelled a similar path to power, playing on ideas about a venal Brussels elite in a campaign that led to the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union. Authoritarians in Hungary and Poland have corrupted state structures so thoroughly that, at one point last year, the EU appeared to stake its future – in the form of its budget and its coronavirus recovery fund – on strengthening the rule of law in those countries. Public discontent with corruption, real and imagined, has unsettled Western societies. Yet Europe and the United States have an opportunity to redirect this energy towards strengthening their political systems and renewing their alliance.

The opportunity has arisen out of two recent developments. The first is the advent of Joe Biden’s presidency, which came shortly after the US Congress passed some of the strongest anticorruption legislation in decades. Layered within the National Defense Authorization Act, the legislation is designed to outlaw the anonymous US shell companies that have long benefited corrupt leaders and criminal organisations across the world. Biden has begun to build on this by prioritising initiatives to “close the loopholes that corrupt our democracy”, as he put it during his presidential campaign. The State Department announced in February 2021 that it would counter this “global threat to security and democracy” by enacting reforms that fulfil the United States’ international commitments on anticorruption, and by strengthening institutions that protect the rule of law, as well as civil society.

The second development is Europe’s post-Trump effort to rebuild the transatlantic relationship. In a joint statement following its June 2021 summit with the US, the EU stated that it would “lead by example at home” through “concrete actions to defend universal human rights, prevent democratic backsliding and fight corruption”. This came days after the Biden administration imposed anticorruption sanctions on several politically influential Bulgarians – measures that were long overdue. In the build-up to the administration’s planned Summit for Democracy, European states have a strong diplomatic incentive to address the causes of widespread public concern about graft: 62 per cent of EU citizens say that government corruption is a “big problem”, according to a survey Transparency International conducted late last year.

Domestically, this means punishing and deterring blatantly illegal abuses of entrusted power – as well as acts in a legal grey zone that cause voters to see the political system as corrupt – and strengthening the institutions that prevent such abuses. Internationally, it means countering authoritarian states’ increasing use of what Biden calls “strategic corruption” to achieve their political goals in various regions, not least Europe. Such threats often form part of a continuum that runs across national borders – as he observed in 2018, commenting that “there is ample evidence of dark money penetrating other democracies, and no reason to believe we are immune from this risk.”

For Western policymakers who focus on anticorruption, much of the challenge lies in countering graft in ways that citizens notice, understand, and support. The complex and obscure nature of many corruption networks – running through weakly regulated, low-profile legal and financial structures in multiple countries – is hard to fit into a compelling political narrative about a government’s commitment to the rule of law. The challenge is particularly acute in relation to strategic corruption, which is motivated by not just personal gain but also a competition for influence between states. Biden argued in 2017 that authoritarian leaders are able to use this form of corruption as a weapon due to “the difficulty of proving that it even exists, or that its purpose is political”. As far as most citizens of Western countries are concerned, many anticorruption initiatives are similarly invisible. Such initiatives are often diffused across a range of government bodies that voters are unlikely to associate with the anticorruption fight either in their own societies or as an element of foreign policy, such as relatively low-profile financial regulators and units in intelligence agencies.

This paper argues that the US and Europe should strengthen their defences against graft in a way that has sustainable public support. To achieve this, they should establish national anticorruption institutions of a kind unseen in the West. In time, the US government and its European counterparts should ensure that these institutions collaborate with one another – as part of a network designed to counter kleptocrats and other powerful corrupt actors who threaten the Western alliance. The institutions would coordinate domestic and external anticorruption efforts, while helping facilitate foreign governments’ work in areas such as judicial and security-sector reform.

The paper focuses on the anticorruption element of Biden’s “foreign policy for the middle class” and its implications for Europe. The first part of the paper discusses the domestic origins of his concerns about corruption, including the ways in which graft has damaged US citizens’ faith in the political system. The second part analyses the common threats that corruption poses to Europe and the US. The third and fourth parts discuss two focal points for transatlantic cooperation against graft: kleptocrats’ and authoritarians’ use of strategic corruption to exert influence abroad; and corruption enabled by financial multinationals. The final part describes how the new anticorruption institutions could operate in practice.

Throughout, the paper draws on some of the aspects of anticorruption that Biden appears likely to prioritise. It shows that, by establishing such institutions, Western countries could simultaneously strengthen their alliance, raise one another’s governance standards, and address public disillusionment with their political systems.

The domestic origins of Biden’s anticorruption campaign

Biden’s foreign policy for the middle class is based on a simple idea: ensuring that the everyday concerns of Americans have greater influence on the United States’ relationship with the rest of the world. As he argued in his first foreign policy speech as president, “there’s no longer a bright line between foreign and domestic policy. Every action we take in our conduct abroad, we must take with American working families in mind.” It will be important for European leaders to understand some of these concerns if they are to anticipate shifts in US anticorruption policy under the administration.

While Biden faces a broader array of crises than many of his predecessors, he has said several times that he will prioritise efforts to tackle corruption. This may seem an odd choice, given that US administrations of recent decades have often paid little attention to the issue. Yet one of Biden’s defining views of international relations appears to be that democracies are locked in an existential battle with corrupt authoritarian states. And, in the aftermath of the Trump era, there are compelling domestic reasons to prioritise anticorruption. Much of the motivation for Biden’s new approach likely comes from Americans’ recognition of how graft is eroding the political system.

American disillusionment

The outcome of Trump’s second impeachment trial, announced in the Senate on 13 February 2021, was a low point for accountability in American politics. Only 57 senators voted to convict the former president of inciting an insurrection, falling short of the two-thirds majority required to find him guilty under the constitution. Among the 43 who voted for acquittal, minority leader Mitch McConnell sharply condemned Trump while maintaining a four-year habit of enabling his personalisation – and monetisation – of the presidency. Yet McConnell’s rhetoric has not always been empty. As a university lecturer in the 1970s, he claimed that the requirements for political success in America are “money, money, money”. That statement was never completely inaccurate, but it would prove increasingly apt in the intervening decades – partly thanks to his efforts.

Between 1986 and 2018, the cost of winning a seat in either chamber of Congress more than doubled (after adjusting for inflation). On political action committees for congressional elections during the period, the share by which corporate spending outstripped labour spending rose from roughly 50 per cent to around 300 per cent. The Supreme Court ruled in 2010 that corporations have a right under the First Amendment to spend unlimited funds on election campaigns, and can do so without posing a significant threat of corruption – that, put another way, such spending is a form of free speech. Six years later, the court greatly narrowed the basis on which elected officials can be convicted of bribery. Meanwhile, US policymaking became ever more privatised. For instance, during the creation in 2017 of Trump’s signature fiscal policy, a rushed multitrillion-dollar tax reform that primarily benefited the top 1 per cent of households, the 130 staff on the Senate’s finance and joint taxation committees contended with around 6,200 lobbyists. No wonder that, according to a Gallup poll taken in 2018, 72 per cent of Americans said that corruption is widespread in the US government – a level of cynicism slightly higher than that of Russians in their views of the Kremlin.

Biden began to emphasise the importance of such issues in his campaign for the presidency, arguing that “for too long, special interests and corporations have skewed the policy process in their favor with political contributions.” He promised to sign a presidential policy directive that would establish combating corruption as a core national security interest and democratic responsibility – a commitment that he fulfilled in June this year (shortly before Congress established a bipartisan caucus against kleptocracy).

Key figures in his administration have elaborated on the idea of a foreign policy for the middle class and the need to tackle corruption at home and abroad simultaneously. Secretary of State Antony Blinken referred last year to “a crisis in the credibility of our institutions … corruption permeating our systems in different ways”. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan drew links between economic policy and efforts to counter kleptocracy. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called for new measures to strengthen US anti-money laundering laws (and to address the related issue of global tax avoidance). And USAID Administrator Samantha Power identified anticorruption as crucial to rebuilding the United States’ reputation as a competent international actor with unique capabilities – an effort that should begin at home.

In this context, ‘the middle class’ appears to be a broad concept related to the societal damage caused by dangerously high levels of inequality, numbering as the US does among the 60 nations worldwide with a Gini coefficient higher than 40. As such, the Biden administration’s approach to corruption is likely to have three main strands: restoring Americans’ faith in their institutions; reforming domestic political and economic systems that facilitate corruption globally; and working with foreign allies to counter the threats that kleptocracy poses to democratic states. Nonetheless, at times, these strands are so interwoven as to be indistinguishable from one another. One can see this in a series of scandals and disasters that have reverberated between the US and Ukraine in recent years.

Dark money in the heartland

As a target of Russian military aggression and a member of the Eastern Partnership, Ukraine has received a great deal of attention from European policymakers in the past decade. Support for the country’s battle against Russian-backed kleptocrats – who aim to weaken the Ukrainian political system enough to draw it into the Kremlin’s sphere of influence – is important to the EU’s efforts to stabilise its neighbourhood. For similar reasons, Ukraine has played an outsized role in the anticorruption elements of US foreign policy – and in Biden’s recent career.

On a visit to Kyiv shortly after the country’s 2014 Revolution of Dignity, he used meetings with leaders such as then-presidential candidate Petro Poroshenko to implicitly link US aid to Ukrainian anticorruption reforms. By the following year, Biden’s thinking on the issue appeared to have evolved: he told an audience in Washington that corruption had become a strategic weapon for hostile states such as Russia, as seen in its conflict with Ukraine. Between the two events, Biden’s son took a seat on the board of Ukrainian energy company Burisma. The appointment would eventually spark a scandal that, while it led to an illuminating debate on the US influence industry, seemed largely based on unsubstantiated claims by Trump and his followers.

In 2018 two US citizens with ties to Dmitry Firtash – a Ukrainian oligarch who allegedly worked with the Kremlin to control energy markets in central Asia and eastern Europe – joined Trump ally Rudy Giuliani, along with two former employees of Ukrainian law enforcement agencies, in a smear campaign that targeted Biden (as well as the then-US ambassador to Ukraine, Marie Yovanovitch). The following year, Trump was impeached for allegedly threatening to withdraw US support for Ukraine unless Kyiv: produced compromising material on Biden; disputed evidence used in the trial of Paul Manafort; and claimed that former Ukrainian officials were behind the 2016 hack of the Democratic National Committee. McConnell and others ensured that the Senate dismissed the impeachment charge. Still, they could do nothing to dispel the impression that the Ukrainian political system, long troubled by endemic corruption, had more parallels with its US counterpart than anyone cared to admit.

If the network around Firtash showed how kleptocracy could warp US politics and policymaking at the highest level, the network around two other Ukrainian oligarchs revealed how it could damage the lives of American citizens more directly – including the middle class that Biden seeks to represent and protect. Hennady Boholyubov and Ihor Kolomoisky are perhaps best known in the West as the former owners of Ukraine’s largest financial company, PrivatBank. In 2016 Kyiv nationalised the bank in response to an alleged scheme to defraud Ukrainian taxpayers of around $5.5 billion, which funnelled money through the firm’s Cypriot branch. This is just one of the many cases in which Boholyubov and Kolomoisky have allegedly exploited Western economies’ openness to flows of stolen funds.

According to research by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), the two magnates bought up an array of companies and properties in the US between 2006 and 2016. They were allegedly assisted in the task by a European-headquartered firm, Deutsche Bank, which appears to have moved $750m into the US for Kolomoisky over several years – even as its employees repeatedly raised concerns about the nature of the transactions. In the process, Boholyubov and Kolomoisky transferred funds through companies in secrecy jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Cyprus, and Biden’s home state, Delaware.

They bought up a steel factory in Ohio, an inactive Motorola plant in Illinois, an office tower in Louisville, and more than 20 other properties – at one point becoming the largest commercial landlords in Cleveland. These supposed investments fell into a pattern of neglect consistent with large-scale money laundering networks. Multiple violations of safety and environmental laws allegedly led to a series of accidents that severely wounded workers, including explosions at factories in Indiana and Ohio in 2010 and 2011 respectively. As the ICIJ found, at least four steel plants owned by the oligarchs filed for bankruptcy. Many of the properties racked up unpaid taxes, utility bills, and debts to local businesses.

Ukrainians will be all too familiar with the legacy these transactions had for some Americans: physical and emotional scars, lost jobs and economic ruin, and fury at a system that seems to allow the wealthy to operate with impunity. It appears to have been Ukrainian regulators and the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) – not US regulators, nor the firms profiting from many of the transactions – that were primarily responsible for halting the flow of Kolomoisky’s money into the US, in 2016. In this way, an anticorruption institution in a distant country helped protect American citizens.

The Biden administration sanctioned Kolomoisky in March 2021. Yet, if the US had in place a dedicated domestic anticorruption institution, Americans would likely not have been so vulnerable in the first place. Such an institution, working in a network with those of the country’s allies, could have limited the financial and political reach of figures such as Firtash, Boholyubov, and Kolomoisky.

Europe’s and America’s shared corruption problems

Large-scale corruption networks of these kinds, running through governments or through exclusively private channels, are as much a problem for Europe as for the US. The tawdry fireworks of the Trump presidency may have left some citizens of the EU and the UK with a sense of moral superiority – a conviction that, however bad things were, Americans had it worse. The reality is less clear-cut.

Like the US, Europe is home to many voters who view the political system as synonymous with graft. According to a survey the Pew Research Centre conducted in 2020, the share of voters who see most politicians as corrupt is 46 per cent in France, 45 per cent in the UK, and 29 per cent in Germany. As shown by a study the European Council on Foreign Relations conducted in 2020, an average of 36 per cent of voters in Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden are concerned about financial waste and corruption in countries’ use of the EU coronavirus recovery fund.

There could be some recency bias in all these findings. The surge of public procurement in response to the pandemic led to a series of high-profile corruption cases across Europe. The crisis has shown European citizens how, by siphoning off public funds intended for life-saving treatment or prevention measures, corruption networks can harm people they know.

In some European countries, the pandemic hastened the erosion of institutions that traditionally guard against the abuse of entrusted power. Western policymakers generally recognise that, in states such as Iraq and Ukraine, anticorruption reform is closely linked to these institutions’ capacity to enforce the rule of law. Without such protection, there is little to prevent politicians and other powerful figures from engaging in graft. However, Western governments have not always applied this logic at home. Today, public discontent with corruption among the elite runs much deeper than the effects of the pandemic.

In March this year, a court in France handed down a three-year sentence to former president Nicolas Sarkozy for attempted bribery of a judge in 2014. The decision came a decade after the conviction on corruption charges of another former president, Jacques Chirac. In both cases, the French courts signalled that no one is above the law. And neither Sarkozy nor Chirac committed these crimes while serving as president. Yet their behaviour likely heightened French voters’ cynicism about the options the political system presents them with at elections. Former prime minister François Fillon, who was forced to drop out of the 2017 presidential race due to his involvement in an embezzlement case, will have done nothing to restore their faith if he – as reported – becomes the latest retired European politician to join the board of a Russian energy firm.

In the UK, the government has made several attempts to weaken the institutions that guard against the abuse of entrusted power. Its contorted, four-year preparations to leave the EU led it to attack the independence of the judiciary and – with no apparent sense of irony – the supremacy of parliament. More recently, the government introduced legislation on Northern Ireland that would violate international law in a “specific and limited way”; took an approach to pandemic-related public contracting that, as a poll by Survation found, 59 per cent of voters see as corrupt; and put forward a bill that appeared to severely limit the right to protest (among other draconian measures). The government recently committed to using sanctions to tackle money laundering. However, it was not until March this year that the UK authorities launched their first criminal proceedings against a major bank, NatWest, under 2007 money laundering regulations.

In Germany, a recent flurry of scandals involving lawmakers and authoritarian-backed corruption networks have – as ECFR’s Majda Ruge and Gustav Gressel write – threatened to damage public faith in the political system. And the collapse of Wirecard last year provided one more example of how the country has failed to counter corruption enabled by financial multinationals. The payments giant met its fate amid allegations that it was entangled in money laundering networks, fraud schemes, Firtash’s dealings, and even Russian intelligence operations. Berlin reportedly considered bailing out the firm, only to decide against it at the last minute. Even before the story broke, it was hard to avoid the conclusion that Europe’s most powerful state lacked the power (or inclination) to uphold the rule of law in the financial system. For instance, Deutsche Bank has been implicated in everything from the Russian mirror trades scandal and violations of sanctions on Iran and Syria to, as discussed, Ukrainian oligarchs’ dubious acquisitions in the US. Since 2002, the company has paid more than $15 billion in fines to US regulators for a litany of crimes. But none of this stopped Chancellor Angela Merkel from delivering a welcome speech at the bank’s 2021 new year’s reception.

Meanwhile, revelations about money laundering through firms such as Swedbank and Nordea Bank have tarnished the reputations of several Scandinavian countries. Chief among these cases is that at Danske Bank, which allegedly facilitated the movement of around $230 billion in stolen funds through its Estonian branch between 2007 and 2015. For citizens who followed the story closely, Denmark likely became one of many European states whose self-image as a committed democracy contrasted with its role in enabling kleptocracy elsewhere in the world.

The situation in other parts of the EU is even more disconcerting. The rise of corrupt leaders in Poland and Hungary is well documented, involving their governments’ alleged efforts to curtail the independence of the judiciary and divert EU funds to political allies, among other transgressions. In the last few years, major corruption scandals have roiled nations such as Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia – sometimes leading to widespread protests. The first EU report on member states’ adherence to the rule of law, published in September 2020, may have several problems with its methodology. But it found serious weaknesses in the democratic standards of these countries (and even shortcomings related to civil society, criminal procedure, and freedom of expression in Greece, Italy, and Spain respectively). Judging by the report, Europeans might ask whether the EU’s contribution to democratisation ends with the accession process – especially given that its Cooperation and Verification Mechanism does not seem to have improved these standards in either of the two countries in its remit, Bulgaria and Romania.

The EU’s reliance on unanimity hobbles its institutions’ efforts to address corruption in member states. The bloc was reminded of this last November, when Hungary and Poland vetoed its budget and coronavirus recovery fund rather than accept financial constraints designed to deter further violations of the rule of law. The EU eventually relented by kicking the dispute to the European Court of Justice – apparently in the hope of finding a legalistic solution to a political problem. Influential European countries could still pressure Hungary, Poland, and other member states into democratic reforms. But they would probably have to do so as part of an anticorruption alliance – a coalition of the willing – rather than through the unanimity-locked structures of the EU.

In light of all this, European leaders who are concerned about the decline of democracy at home and abroad should share many of Biden’s reasons for launching an international campaign against corruption. If the Trump era helped Biden recognise why anticorruption is an important element of a foreign policy centred on domestic concerns, European states should react to their own struggles with graft in a similar fashion.

It is crucial for Western countries to not only tackle transnational corruption effectively but to be seen to be doing so in ways the public finds persuasive and responsive. Multilateral agreements are often useful for addressing international problems. But as shown by the EU’s fiscal rules – which it was forced to suspend during the pandemic – they can lead to policy that is rigid, ill-suited to dealing with crises, and short on democratic legitimacy. When leaders make socially transformative decisions for democratic states but voters have no way to hold them accountable, public disillusionment with democracy grows.

Some European governments may reject Biden’s view of international relations as a struggle between democracy and autocracy, but they are all looking for ways to rebuild the transatlantic relationship after a difficult four years. Anticorruption policy provides a way to do so without vanishing into the kinds of grand strategy and geopolitical manoeuvres that often seem remote from citizens’ lives. This policy should involve the creation of national anticorruption institutions to signal to allies and, more importantly, voters that the government is committed to tackling graft. These institutions should initially focus on two main themes: strategic corruption, and corruption enabled by financial multinationals.

Strategic corruption

Trump is culpable for much of the recent damage to the Western alliance, but not all of it. European leaders occasionally appeared to use his presidency as an excuse to pursue controversial policies they would have favoured anyway, justifying their actions as an assertion of ‘European sovereignty’. On issues such as economic relations with China, the euro’s global role, and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, the volatile bully in the White House made for an ideal foil in arguments that seemed more focused on commercial opportunities for multinationals headquartered in Europe than on the long-term interests of European citizens. After the US shifted towards stark unilateralism under Trump, its traditional allies in Europe had fewer opportunities to strengthen – but also fewer responsibilities to maintain – the transatlantic relationship.

However, it is a new era. In his first major speech as secretary of state, Blinken mentioned the threat of corruption three times and emphasised that “partnership means carrying burdens together, everyone doing their part – not just us”. “Wherever the rules for international security and the global economy are being written”, he said, “America will be there”. Blinken’s statement seemed to signal that, while the transition from Trump to Biden has many benefits for Europe, it also comes with new responsibilities.

By establishing a network of national anticorruption institutions, European countries and the US could engage in the kind of cooperation against common threats that would help repair the Western alliance. Through these institutions, the allies could improve the transparency and domestic legitimacy of their own anticorruption campaigns. This would, in turn, push them to replicate the elements of one another’s campaigns that proved effective. Eventually, some of the institutions’ most important work could focus on issues that required a great deal of introspection – such as, in the British case, London’s outsized role in international money laundering networks. But, in the search for common ground on which to rebuild the transatlantic relationship, the institutions could initially focus on strategic corruption in the following areas.

The EU’s neighbourhood. The EU and the US both want to stabilise countries in the bloc’s neighbourhood and, in some instances, protect their development into functioning democracies and draw them into the Western alliance. This is why European and American policymakers have sometimes sought to limit the power of oligarchs who warp, through corruption, the political systems of states to the EU’s east and south.

It would be impossible to address the strategic challenges Europeans face in these nations – be it political turmoil in post-Soviet countries or conflict in the Middle East – without accounting for the governance problems created by kleptocrats. Governments’ suppression of protests against a corrupt political system was at the heart of some of the deepest crises in the EU’s neighbourhood in the past decade, from the conflict in Syria to the state violence that helped spark the 2014 revolution in Ukraine.As Biden remarked in 2015 when discussing Russia’s use of strategic corruption in Ukraine, “we need to help some of the newer EU nations and those aspiring to join them, to shore up their institutions, to put in place the mechanism required to avoid becoming vulnerable to this new foreign policy weapon.”

China. By labelling China as a “systemic rival” in 2019, EU policymakers expressed some of the same concerns that their US counterparts had long held about Beijing’s growing power. The EU and the US are still at odds with each other on a range of China-related issues. Yet the need to combat China’s alleged use of strategic corruption should be a point on which they can agree.

In recent years, Beijing has reportedly expanded its influence through the use of bribery and other corrupt bargains with companies and political leaders in Africa, often as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. For example, massive inflows of Chinese investment have allegedly helped support the corrupt, authoritarian regime in Djibouti, a country that is in a strategically important position on international trade routes and that hosts both US and Chinese military bases. Such Chinese activities could thwart the EU’s efforts to deepen its economic relationships with countries in Africa – efforts that the bloc’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, advocated last year as part of the response to the pandemic. In doing so, he developed Europeans’ everyday health concerns – their heightened sense of vulnerability to China as a systemic rival – into an element of foreign policy. European leaders should respond to public concerns about corruption in a similar way.

The UK, for its part, could be a willing partner in initiatives to address Chinese-backed corruption in Africa, given its recent moves to oppose Beijing’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and its discussion of corruption and illicit finance in its 2021 integrated review. The EU, aiming to show that it can provide a democratic alternative to Chinese economic activities in Africa, could start by curtailing corruption networks’ alleged use of the euro to bypass US sanctions designed to prevent exploitation of African countries’ natural resources – and perhaps by building on the G7’s proposal for a Clean Green Initiative.

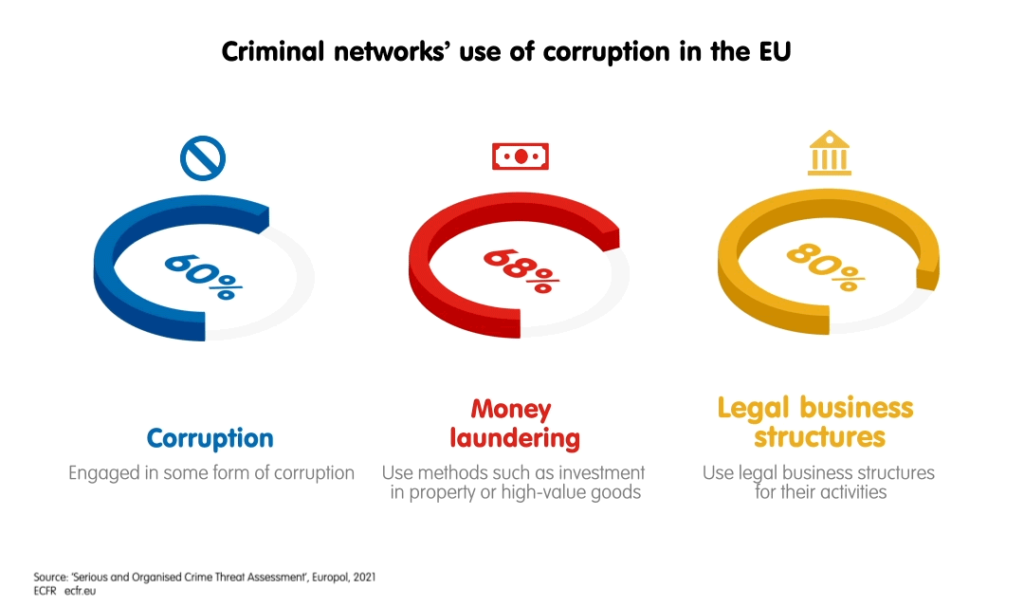

Transnational organised crime groups. Europol published in April 2021 its first threat assessment of serious and organised crime in four years. The report finds that 60 per cent of organised crime groups in Europe regularly use corruption to achieve their ends, that legal business structures are important to more than 80 per cent of criminal networks, and that such activity has a severe impact on the lives of EU citizens. Some organised crime groups occasionally work on behalf of authoritarian states such as Russia. European countries could, alongside the US, address the anticorruption aspects of these problems, initially by targeting groups that are equally threatening to America and Europe.

One such organisation is the Lebanese-based Hizbullah, which the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence listed alongside Cuba, Iran, Russia, and Venezuela in its report on foreign interference in the November 2020 presidential election. Trump openly encouraged foreign entities to interfere in US elections. Biden has a wholly different attitude to such behaviour. He recently announced new sanctions on Russia in response to the activities discussed in the report, after declaring that the country would “pay a price” for its interference.

A similar punishment could await Hizbullah. Its importance in Lebanese politics aside, the group is remarkable for the sheer ambition and geographical scope of its alleged involvement in transnational organised crime and corruption. Its reported activities include exploiting Gambia’s economy under kleptocrat Yahya Jammeh; backing the corrupt authoritarian government of Venezuela; forming partnerships with Mexican and Colombian narco-terrorist organisations; laundering money through a bank linked to the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons programme; trafficking drugs such as cocaine and Captagon into the US and Europe; and even stockpiling explosives in London. The revenue from such activities allegedly helps support Hizbullah’s military and political operations in Lebanon, Syria, and other parts of the Middle East.

In all three of these areas, European countries should cooperate with the US to destroy the financial networks that support kleptocrats’ operations. This should be one of the main aims of national anticorruption institutions as they coordinate the sometimes-disjointed anticorruption work of – for instance – financial regulators, intelligence agencies, law-enforcement bodies, ethics committees, and economic policymakers. The political impetus to do so can come from the high levels of public concern about corruption in many Western countries. As with the Africa policy advocated by Borrell, it will be up to European and US leaders to explain to voters how tackling a strategic problem abroad protects citizens at home.

Corruption enabled by financial multinationals

The European and American financial systems are so integrated that it is sometimes impossible to tell where one ends and the other begins. Kleptocrats have exploited the weaknesses and uncertainties of this integration to create far-reaching networks of impunity in Europe.

The global financial system is distinct from many other forms of infrastructure in the role it assigns to Western multinationals. Entities such as central banks and the SWIFT messaging service are vital to the system. However, the system is largely made up of major financial companies – several of which have balance sheets larger than the GDP of most countries.

In some ways, such firms are to financial infrastructure what roads and highways are to transport infrastructure. Most international transactions flow through them. And Western states have largely delegated oversight of financial crime to financial multinationals, which spent an estimated $180 billion on compliance with money-laundering and sanctions rules in 2020 alone. But these companies are not up to the task.

As seen in the torrent of corruption scandals that has engulfed financial multinationals such as HSBC, BNP Paribas, Danske Bank, Deutsche Bank, and Goldman Sachs in the past decade, megabanks have become one of the main mechanisms through which kleptocrats – who have stolen the wealth of their home states – expand their financial and political power internationally. If Western governments are to counter this threat, they will require a new approach to financial multinationals. Put another way, they will need to adjust the relationship between the state and the market.

Biden’s campaign against graft will almost certainly reverse many policies of his predecessor – who, for example, reportedly attempted to cut billions of dollars from aid programmes designed to combat corruption in states such as Ukraine. However, the most consequential shift in anticorruption policy under Biden could centre on the relationship between the state and the market. This would mean a break with not just Trump but several presidents before him.

Senior members of the Biden administration have signalled such a shift. In July 2020, Blinken discussed the challenges for the US that come from “a huge diffusion of power away from states, and a growing questioning of governance within states”. (He appeared to be referring to states’ relationships with all sorts of entities – not just the market.) Sullivan commented on the issue more directly the previous month. He said that a “reckoning” was taking place in America about the future of the economy, and that “it’s time for foreign policymakers to get into the game as well”. In an article co-written with Jennifer Harris earlier in the year, Sullivan argued that some aspects of Washington’s geo-economic policy have had little benefit for middle-class Americans, citing trade negotiations that prioritised Goldman Sachs’s access to Chinese financial markets.

In 2020 the bank – nicknamed ‘Government Sachs’ for its once and future employees’ ability to gain positions of power – accounted for around 90 per cent of US regulators’ fines for non-compliance with rules on anti-money laundering, know your customer procedures, data privacy, and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive. Most of these penalties related to the firm’s involvement in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) corruption scandal, which implicated former prime minister Najib Razak and businessman Jho Low in the theft of billions of dollars from the Malaysian sovereign wealth fund.

Goldman Sachs is among many “systemically important institutions” to have received multibillion-dollar fines for their entanglement in international corruption networks. Governments apply the label to financial multinationals in recognition of the fact that their failure could destabilise the global economy. Yet, even with the designation in place, most of these firms have broken the law so often that this appears to be part of their business models.

The $6.8 billion in fines Goldman Sachs paid to regulators around the world for its involvement in 1MDB is significant but not unusual. Penalties such as this one almost certainly fail to capture the true scale of megabanks’ crimes, given the many weaknesses of governments’ financial regulatory and enforcement regimes. Nonetheless, globally, banks have paid around $320 billion to regulators for violations of money laundering, terrorist financing, market manipulation, and other regulatory standards since 2008. Many of these fines may be unconnected to corruption networks, but those that are so connected likely run into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Deutsche Bank’s alleged role in the Boholyubov and Kolomoisky network should have shown Western governments how megabanks’ untouchable status can harm citizens at home. So should have the financial fallout from the scandal at Danske Bank (a case that the European Banking Authority eventually declined to investigate). Yet megabanks’ dedication to reoffending suggests that they have acquired such an important role in the economy that governments dare not hold them to account as they would a smaller company in the same industry.

These kinds of leviathan firms have often been central to the threat that corruption poses to Western societies. Long before the era of financial globalisation or even the oligopolies of the Gilded Age, the East India Company showed how destructive it could be for governments to allow private interests to acquire powers usually reserved for states.

At the height of its influence in the eighteenth century, the trading firm plundered India so remorselessly that it could afford to maintain a standing army larger than that of any Asian country, and to corrupt the British political process by buying off MPs representing “rotten boroughs”. The East India Company’s dominance over much of the British economy seemed to make it indispensable. It was not until the 1786 impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of India and a former employee of the firm, that elements within the British state made a convincing attempt to address the threat. Edmund Burke, who led the impeachment, condemned Hastings for what he called “geographical morality … as if, when you have crossed the equatorial line, all the virtues die”. “Every other conqueror”, Burke added, “has left something behind him”.

That impeachment trial ran between 1788 and 1795 but – like both of Trump’s – ended in failure. As historian William Dalrymple shows, an enterprise that began in 1600 with a pioneering commercial idea, the joint-stock company, would eventually cut a wake of devastation halfway across the world and corrupt the politics of its home state.

Modern financial multinationals are far from becoming as destructive as the East India Company – even if, as illustrated by the cases discussed above, they have often engaged in economic exploitation that has severe political consequences at home and in distant countries. However, the history of all these firms has a straightforward lesson for European and American policymakers: left unchecked, concentrations of commercial power produce concentrations of political power. In any society that is troubled by widespread corruption and wants to retain its democratic character, policy on the financial system should be about not only economics but also democratic accountability.

To conduct an effective international campaign against corruption, Europe and the US will require economic policies that account for the ways in which megabanks’ business practices influence politics at home and abroad. Many citizens of Western states likely ignore international cases such as 1MDB, but they are not blind to dysfunction in the global financial system. The biggest recent spike in Americans’ cynicism about corruption in the US government came not under Trump but in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The share of US voters who saw corruption as widespread in the government leapt from 67 per cent to 79 per cent between 2007 and 2013 (before settling at around 75 per cent). A plausible explanation for this trend is that a growing number of Americans believed the government had placed the welfare of financial multinationals above that of citizens.

Conclusion and recommendations

Corruption poses two main threats to Western democracies. The first is that, in many European countries and the US, an unsettlingly large share of voters see the domestic political system and their elected leaders as corrupt. Western governments need to address this disillusionment – which helped bring Trump and others like him to power – if they are to sustain public engagement with democratic politics.

The second threat comes from the way in which authoritarian states use corruption to build up their political and economic power in the West, as well as places such as eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. When the Kremlin coordinates with Ukrainian oligarchs and Beijing sponsors African autocrats, they undermine Europe’s efforts to bring stability, shared prosperity, and democratic accountability to these regions. When authoritarian regimes appoint retired Western politicians to lucrative roles in state-owned companies, or appear to covertly fund Western political parties, they undermine voters’ faith in the political system and, perhaps, shape policy in line with their interests.

Traditional multilateral initiatives such as the UN Convention against Corruption can help address the second of these threats. But they cannot do a great deal about the first. World leaders’ declarations in Geneva or New York will restore little public faith in the domestic political system if citizens regard these same leaders as corrupt. This dynamic also applies in Brussels. The EU and its member states, including the UK in its time, have made many a public commitment to democratising Europe. Yet they have failed to prevent the erosion of democratic standards and institutions in countries such as Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and others – or to bring democratic accountability to every part of the financial system.

One of the main challenges for Europe is in dealing with these two threats simultaneously: countering strategic corruption in a way that addresses Europeans’ concerns about graft in the domestic political system. In this sense, on anticorruption, European countries need their own foreign policy for the middle class.

When voters complain that the government is corrupt, they are saying that it primarily serves private interests and, as a result, has lost its democratic legitimacy. Therefore, the solution to this disillusionment should come from the kinds of institutions that help generate and mediate such legitimacy. In even the most pro-EU countries, these are primarily national institutions. This is because national elections are the chief means through which citizens assert their political views and grant politicians the authority to lead. National institutions can represent voters with the flexibility, visibility, and responsiveness that are lacking in grand multilateral initiatives and strategies.

The DfID model

A promising model for national anticorruption institutions is the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID). Last year, the British government folded the institution into what was then the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). The establishment of DfID two decades earlier came as part of an attempt to ensure that the UK achieved one of its strategic goals: global poverty reduction. The government of the day reasoned that this was important enough to warrant a more focused, independent approach – and that a dedicated institution would improve the transparency and accountability of spending on foreign aid. Otherwise, so the argument went, there was a danger that this strategic goal would be lost among the FCO’s far-reaching aims, which involved everything from inter-state diplomacy to promoting British companies abroad.

Such a fate has befallen many past efforts to counter graft. For example, the US anticorruption programme in Afghanistan was crucial to Washington’s attempt to achieve one of its strategic goals: building a democratic Afghan state. But, as former US military adviser Sarah Chayes recounts, the programme’s work was often sidelined by competing diplomatic, intelligence, and military operations that ran on shorter – seemingly more urgent – timelines. Arguably, if the anticorruption programme had the backing of a dedicated institution such as DfID, it would have found it easier to hold its own in interactions with entities such as the State Department, Central Command, and the CIA.

Another of DfID’s strengths was that it created a politically useful degree of separation from the FCO. Although the two institutions were ultimately under the leadership of the same government, DfID could credibly claim to focus on challenges such as poverty alleviation for their own sake – rather than as part of a quid pro quo involving British diplomatic or commercial interests. As such, it was easier for foreign governments to accept assistance from DfID than from the FCO. An image of impartiality could be important to Western anticorruption programmes abroad, especially in countries in which the government labels organisations that promote democracy as “foreign agents”.

Domestically, much of DfID’s value as a model for anticorruption institutions comes from the public recognition it gained. In some ways, the institution was too well known for its own good, given that its merger with the FCO came after it was caught up in a political dispute about whether the UK spent too much on foreign aid. Nonetheless, according to a survey conducted in March 2020, only 48 per cent of British voters did not know or did not care about the merger. This is a surprisingly low figure for an institution whose programmes had little direct impact on their lives.

Western governments should consider this sort of quasi-independent, DfID-style model when setting up national anticorruption institutions. Institutions dedicated to publicly holding to account powerful political and business leaders at home, as well as abroad, could begin to restore citizens’ faith in the political system. For instance, in the case of Boholyubov’s and Kolomoisky’s US operations, an anticorruption institution could have helped ensure that the government practised in America what it preached in Ukraine. Moreover, such an institution could outlast any one administration, increasing the resilience of the national anticorruption campaign. And, when dealing with transnational corruption networks that run through financial multinationals, the institution’s dual focus on domestic and foreign corruption would enable it to track the operations of these firms wherever they led.

Networked anticorruption institutions

The creation of national anticorruption institutions in this mould should not lead Western states towards unilateralism. Some of the most resilient forms of international cooperation against common threats involve networks of national institutions, such as the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, rather than broad multilateral arrangements. On anticorruption, these coalitions of the willing should include Western states that have a similar commitment to independent institutions and a shared desire to rebuild the transatlantic alliance around democratic norms and standards.

For instance, the UK’s departure from the EU may have damaged its relationship with France more than any event in decades, but citizens in both countries are concerned about corruption in the domestic political system. Collaborating through national anticorruption institutions, France and the UK could support the civil society organisations that have done a great deal to compensate for shortcomings in anticorruption policy in recent years, such as the ICIJ and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. By launching this kind of joint initiative, Paris and London could pressure each other into reforms or investigations when the organisations uncovered evidence of corruption involving French or British companies or politicians. In doing so, they would demonstrate to French and British citizens a national commitment to such reforms. Other governments could join this initiative, thereby demonstrating to voters that they were taking action to address the threat.

Similarly, Berlin and Washington may disagree on issues such as Nord Stream 2, but they both aim to stabilise Ukraine by protecting the country’s political system from the depredations of Kremlin-backed oligarchs. Coordinating their work through national anticorruption institutions, the two allies could punish and deter these corrupt actors by targeting their assets, including those in German- and US-headquartered megabanks.

European countries’ anticorruption institutions could focus on many broader areas. Corporate accountability is one: for instance, following the debacles over Wirecard and Nord Stream 2, the German government could task such an institution with assessing and publicising the corruption risks associated with prominent firms and economic projects that receive high-level political sponsorship. Another such area is the abuse of the legal system: a British institution of this kind could oversee the implementation of legislation to prevent alleged kleptocrats from launching reportedly vexatious lawsuits against journalists and other members of civil society.

However, finance is perhaps the most compelling area in which to begin. In June 2021, the Financial Action Task Force placed Malta on its grey list alongside countries such as Pakistan, South Sudan, and Syria – subjecting the EU member state to increased monitoring due to its reported vulnerability to international money laundering and terrorist financing. Like the sanctions the US imposed on politically influential Bulgarians, this was an indictment of European countries’ defences against large-scale corruption networks.

The European Public Prosecutor’s Office, an EU institution that became operational in June, expressed support for Bulgarian citizens following the sanctions – and may eventually help address some of these broader challenges (not least by raising their public profile). However, the fact that membership of the institution is voluntary bodes ill for its capacity to tackle graft in countries such as Hungary and Poland. Both countries have, of course, refused to join – citing concerns about the impact on their sovereignty.

In the long term, such arguments about sovereignty – be it of the national or European variety – could be one of the greatest impediments to transatlantic cooperation on anticorruption. The sovereignty arguments that the US adopts to condemn European constraints on American tech giants, and that European countries use to criticise US fines on EU-headquartered megabanks, could help preserve aspects of the rules-based economic order that have helped kleptocrats flourish. These aspects of the order embody a kind of libertarianism, in which democratically elected governments have no place interfering in multinationals’ pursuit of commercial opportunities – regardless of their impact on the health of society.

Nonetheless, if European countries and the US can break through these limitations, transatlantic cooperation to strengthen the rule of law in the financial system would set their new anticorruption institutions on firm ground. The US primarily shaped the social norms of the financial system, but European (not least French) policymakers codified most of its legal rules, by working through the EU, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the International Monetary Fund. Far from emerging from some elemental force of globalisation, this Western-dominated system was carefully constructed over decades – and, as such, can be reconstructed to deal with a more chaotic age.

The tendency to erode national institutions – part of the diffusion of power away from states Blinken spoke of – is a feature of both financial globalisation and international corruption networks, as seen in the many money laundering scandals that involve Western megabanks. These firms have profited more than most from the capacity to choose when and how they obey national laws. As legal scholar Katharina Pistor argues, “choosing the law that is most convenient for your own interest should be made more difficult”. This, she observes, “follows from basic principles of democratic self-governance. Democratic polities govern themselves by law. The more loopholes there are for some to escape these laws, the less effective self-governance will be.”

The members of the G7 recently reached an agreement to curtail global tax avoidance by multinationals, which accounts for more than one-third of foreign direct investment in global statistics – “phantom capital” that only appears to be such investment. Although the final form of the deal disappointed many civil society organisations (and appeared to exclude megabanks), the arrangement seems to reflect a recognition by its signatories that globalisation should not retain the extreme form it has had in recent decades.

European countries and the US could build on the G7 agreement, in ways that align with Biden’s foreign policy for the middle class, through the creation of initiatives to counter kleptocrats’ abuse of tax havens, shell companies, and other structures within the international financial system. By establishing national anticorruption institutions that focus on domestic and foreign policy, the allies could pursue their strategic goals while addressing public disillusionment with the political system and the abuse of entrusted power in their own societies.

About the author

Chris Raggett is an editor at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He previously worked as an associate editor at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. His previous publications for ECFR include “Networks of impunity: Corruption and European foreign policy”.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank ECFR’s European Power programme for funding the publication of this paper. He would also like to thank Susi Dennison, Anthony Dworkin, and Nicu Popescu for their helpful reviews of an earlier draft; Adam Harrison for his rigorous editing; and Marlene Riedel and Chris Eichberger for their wizardry in creating the graphics.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of its individual authors.