Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

|

|

For the better part of five decades, photographer Dawoud Bey has aimed his lens at the faces and spaces of Black Americans. Starting in his native New York in the 1970s and, more recently, traveling to the Deep South, he has created a critically acclaimed body of work that both honors history and illuminates everyday life.

Last month, the renowned artist debuted his first-ever Los Angeles solo show, “Dawoud Bey: Pictures 1976 – 2019,” at Sean Kelly gallery in Hollywood. The exhibition, which runs through June 30, is a sampler of his work spanning from his “Harlem, U.S.A.” series to “In This Here Place,” capturing scenes from Louisiana plantations.

The exhibition coincides with the opening of “Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems: In Dialogue” at Getty Center. On view through July 9, that exhibition traces the career milestones of the two celebrated photographers, who are contemporaries as well as friends. As with the gallery show, there are images from Bey’s late-’80s “Street Portraits” series and his three landscape-focused collections — “Harlem Redux,” an exploration of a gentrifying neighborhood; as well as “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” and “In This Here Place,” both of which address the past enslavement of African Americans. Unique to the Getty exhibition is Bey’s “Birmingham Project,” a collection of portraits commemorating the children who lost their lives in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Alabama.

Bey, who lives in Chicago and is a Columbia College professor of photography, traveled to Los Angeles in April for the opening events of both shows. When he wasn’t participating in gallery talks, he visited the local exhibits of artists whose work he admires, including Henry Taylor, Robert Pruitt and Milford Graves. Asked why his first major L.A. shows had only just now come to pass, he quipped, “Well, you can’t invite yourself in, you know; someone has to invite you!”

While discussing his work, he spoke slowly and deliberately, using the same intention and decorum that he’s long applied to his craft. What some viewers may see as impromptu street shots at a hasty glance are so much deeper to him.

“There was a sense — as contradictory as it sounds — of informal ceremony to that work,” he said of his early photographs. “It was very much the kind of thing that one would encounter in going to a studio, except I’m out in the streets. The streets were my backdrop.”

He went on to reflect on the evolution of his practice. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What does it mean to you to have these two shows open together in this town, at this moment in time?

I have spent significant time here in L.A.; I have a community here. I have been supported by institutions here in L.A. — LACMA’s had my work in their collection for a long time, and the Getty too. But to have both of these exhibitions up simultaneously, it’s a moment that I’m grateful for, excited about. It certainly marks a very particular moment, in terms of where I am in my career after 45 years of making work.

One of the reasons I do the work I do is to try to deterritorialize these spaces. That’s very much a part of the ambition that drives my work. I’m acutely aware that when I’m in these spaces, it opens up space not only for other Black artists, but for the larger Black social community. And that really matters to me. I still remember when I was young, I never encountered another Black person in most of the places that I was going to. Making my first trip to Marlborough Gallery on 57th Street [in New York City] and walking into that space, I knew they were aware of my Black presence and I assumed, “A lot of Black teenagers don’t come walking up in here to see Richard Avedon, but I don’t care — I’m here to see it.” That was why it was so gratifying opening night at the Getty to see all of these young Black folks and for them to feel like they had a reason to be there and that this was a place that could be theirs as well.

The first room in the Getty exhibition juxtaposes Carrie Mae Weems’ early depictions of domestic life with your early streetside photographs. Did you ever consider capturing your subjects’ interior lives?

My interest, when I was making portraits, had always been in the public and semi-public self-presentation of Black people in those spaces, not “Can I go home with you?” [or] “Can we cross the threshold to the other side?” I was really interested in the idea of how people are in the public spaces that they live in and wrapping the narrative of those spaces around them.

During that portrait period, how would one of your typical work days play out?

That day would look like me walking around with my conspicuous large-format camera on a tripod resting on my shoulder, drawing attention to myself and looking at people as they were looking at me. I was keenly aware that the people I was asking to participate in this probably never encountered someone doing what I was doing. Sometimes, I would just sit on the stoop, waiting for people to come by. Once I enter into their space with this camera, it’s a very different situation than what existed before. What I worked towards was getting them back to that place before I momentarily disrupted their lives — that appearance of the same kind of casual, relaxed assurance before this stranger walked up to you — to kind of conceptually wind the clock back, like, “Let’s get back to what you were doing before.”

How has your practice changed over the past half-century?

When I started out photographing in Harlem in the 1970s, I was very conscious of the fact that I was not only making work in order to shape perceptions about that community and the Black people that lived in it, I was also making work in response to my sense of the history of Black representation in photography, and the history of photography in general. So that meant that I was aware not only of Roy DeCarava and other Black photographers, such as the Kamoinge collective, but also photographers like Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Dorothea Lange, Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, whose work was considered foundational. I am now working to include a Black voice within the history of the landscape tradition in photography.

I’ve also, from the beginning, drawn inspiration from sources outside of photography, such as music, painting and other art forms. So I don’t think I’ve really changed over that time; I’ve been able to refine and evolve my ideas and sharpen my ability to execute them consistently through rigorous practice.

What sparked that interest in pivoting from portraits to landscape photography?

Conceptually, the “Birmingham” work is what began this desire to intentionally look back and forward at the same time. I decided I would continue by making work about the Underground Railroad. There was no one to make photographs of, so it was clear that I was going to have to let that trope of the portrait go. So it became about the place — the real and imagined places of fugitivity for escaping African Americans. That was preceded by “Harlem Redux,” which was really central to my figuring out a language for making photographs about the Black past and present, in the absence of the portrait being the anchor for the work. By the time I got to making this work about the Underground Railroad and Black fugitivity, I’d become very comfortable with where the two sides, the top and bottom, are of a landscape photograph. Before “Harlem Redux,” it was so expansive, like, “Where does this picture start and stop?”

The “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” work was also, conceptually, deeply informed by DeCarava’s work … also this Langston Hughes poem [“Dream Variations”] with the last couplet that goes: “Night coming tenderly, Black like me.” I thought about the idea of this tender blackness wrapping itself around these fugitive African Americans moving towards the border in order to make their passage to Canada. It became a question of how to make the photographs at such a scale that brought both the expansiveness and the rich physicality of the landscape into the work. People said, “Dawoud, the people disappeared!” I said, “They’re still there, except they’re back here looking out at the world, rather than being looked at.”

How did it feel going from contemporary Harlem, which has been changing so rapidly, to rural landscapes that have remained largely unchanged after all this time?

People are like, “My God, Dawoud! You were at the plantation; I could never go there!” You need to go there. You need to go and feel the places where this history happened. You need to stand there. You need to be present. I’m not standing there in a rage on the plantation or even in a state of emotional turmoil because I wouldn’t be able to do the work that I need to do. I need to figure out a formal and optical strategy for making this place breathe and come alive. Making something is very different than the emotions that we bring. That’s what gets you there, but once you’re there, you gotta do the work.

I’m always conscious that I’m making this work for history. I’m making this work in the service of our ancestors. It’s really to keep our ancestors in the conversation so that they and that history will not be forgotten, even in the context of the Sean Kelly gallery or up on the mountain at the Getty.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

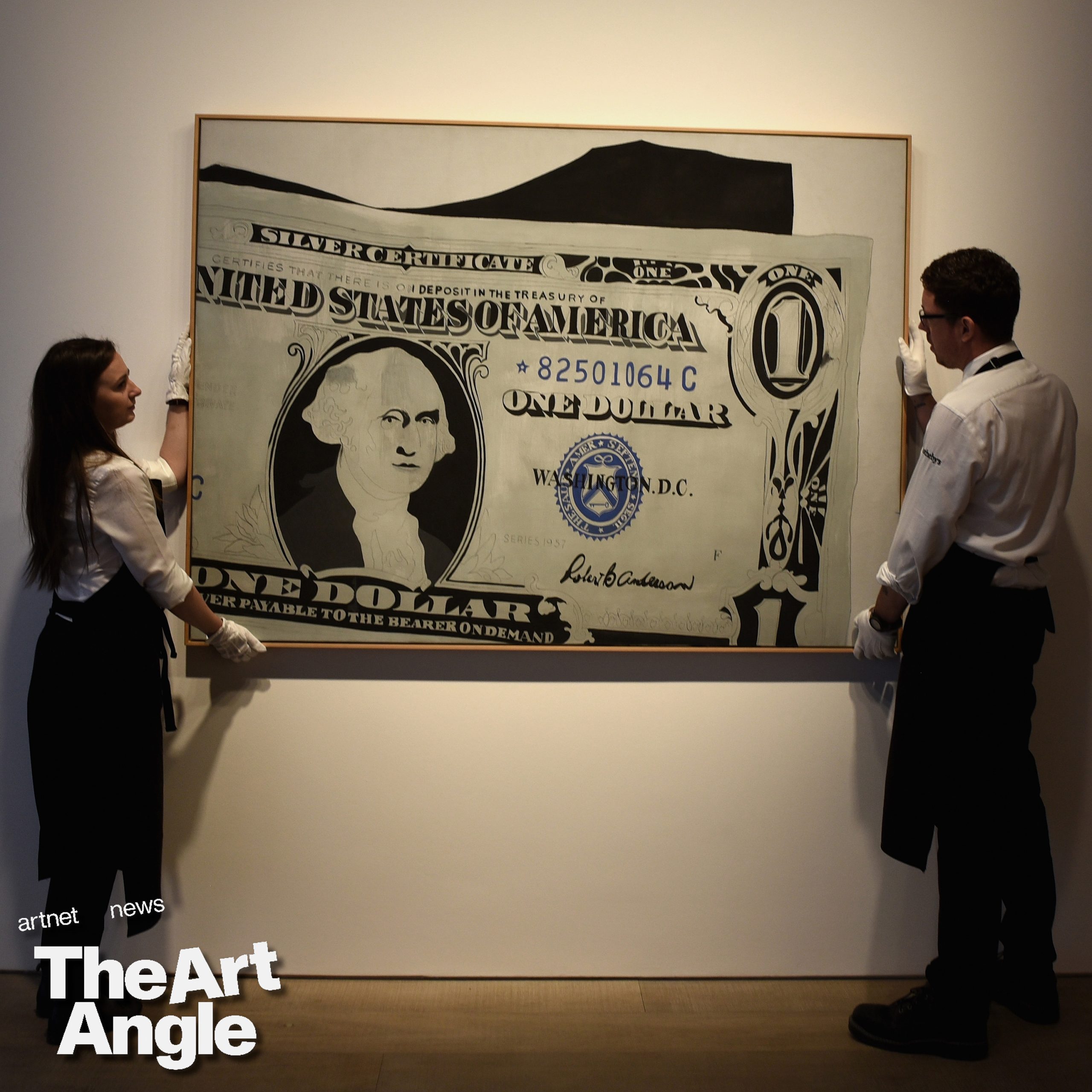

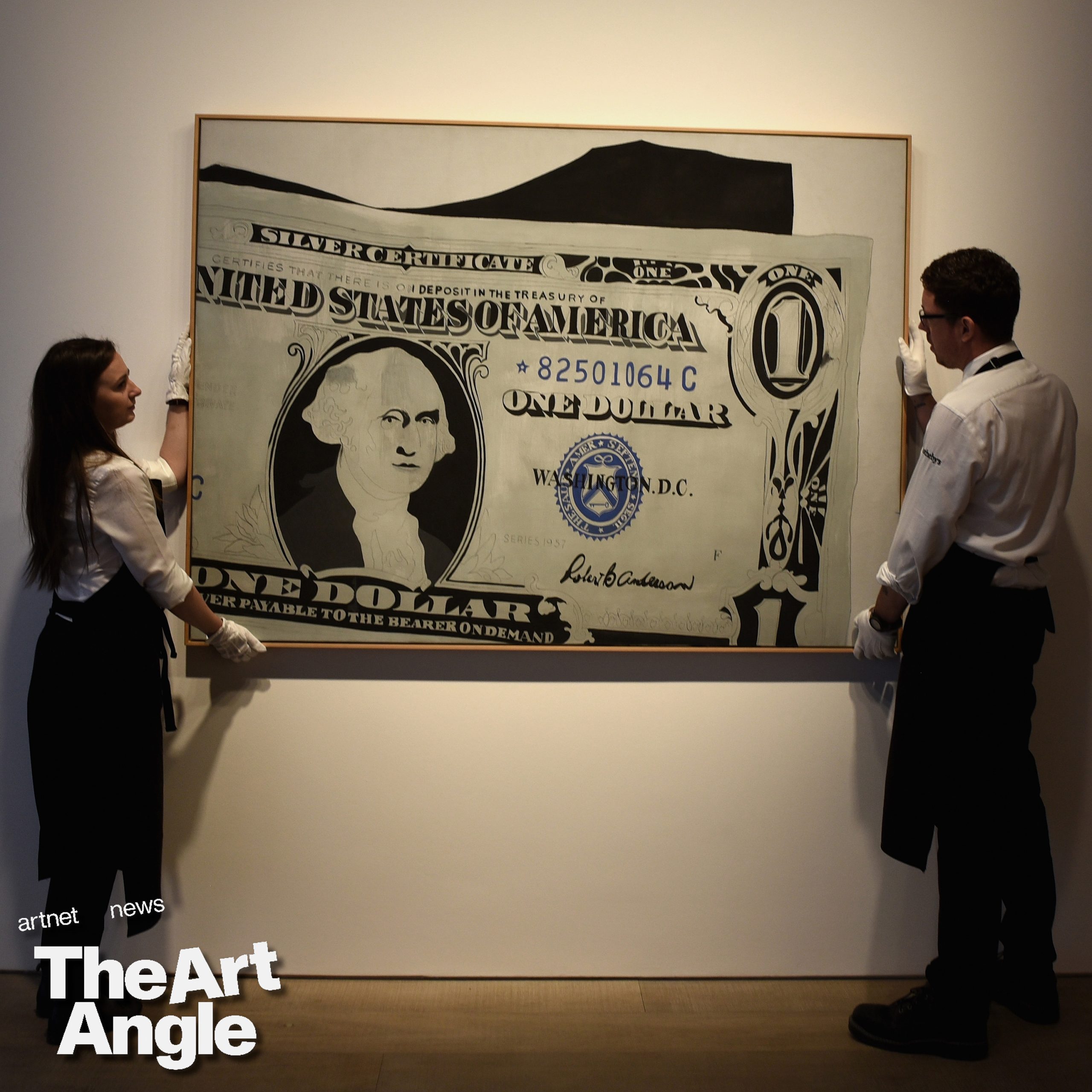

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Digital artist Sam Spratt is living the artist’s dream. This week, he celebrated the opening of “The Monument Game,” his first-ever art show. But it wasn’t a group show in some DIY space in New York, where he is based, like so many artists typically start out, but a solo exhibition in Venice, during the art world’s biggest event of the year—the Venice Biennale. How did Spratt–a virtually unknown name in the art world–make such a tremendous leap? With a little help from his friends, of course, including Ryan Zurrer, the venture capitalist turned digital art champion.

“Something the capital ‘A’ art world doesn’t recognize is the power of the collective, it sometimes leans into the cult of the individual,” Ryan Zurrer told ARTnews during a preview of the opening. “But this show is supported by the entire community around Sam.”

Spratt’s Venice exhibition was put on by 1OF1 Collection, a “collecting club” set up by Zurrer to nurture digital artists working in the NFT space. Since its launch in 2021, 1OF1 has been uniquely successful in bridging the gap between the art world and the Web3 community. Last year, 1OF1 and the RFC Art Collection gifted Anadol’s Unsupervised – Machine Hallucinations – MoMA to the museum, after nearly a year on view in the Gund Lobby. Zurrer also arranged the first museum presentations of Beeple’s HUMAN ONE, a seven-foot-tall kinetic sculpture based on video works, showing it first at Castello di Rivoli in Italy and the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, before sending it to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

With “The Monument Game,” Zurrer is once again placing digitally native art at the center of the art world. While Anadol and Beeple had large cultural footprints prior to Zurrer’s patronage, Spratt is far earlier in his career. But, what attracted Zurrer, he said, was the artist’s shrewd approach to building a dedicated, participatory audience for his work. He did so by making his art a game.

“When I first started looking at NFTs, I spent a long time just figuring out who the players were,” Spratt told ARTnews. “The auctions were like stories in themselves, I could see people’s friends bidding, almost ceremonially, to give the auction some energy, and then other people would come in, and it would get competitive, emotional.”

Spratt released his first three NFTs on the platform SuperRare in October 2021. The sale of those works, the first from his series LUCI, was accompanied by a giveaway of a free NFT to every person who put in a bid. Zurrer had been one of those underbidders (for the work Birth of Luci). While Spratt said the derivative NFTs were basically worthless, he wanted to give something back to each bidder. Zurrer, and others it seems, appreciated the gesture and Spratt quickly gained a following in the Web3 space. The offerings he gave, called Skulls of Luci, became Sam’s dedicated collectors that now go by The Council of Luci. 47 editions were given out and Spratt held back three.

All the works from LUCI are on view at the Docks Cantiere Cucchini, a short walk from the Arsenale, past a rocking boat that doubles as a fruit and vegetable market and over a wooden bridge. Though NFTs typically bring to mind glitching screens and monkey cartoons (ala Bored Ape Yacht Club), the ten works on view depict apes in a detailed, painterly style and emit a soft glow. Taking cues from photography installations, 1OF1 ditched screens in favor of prints mounted on lightboxes.

“We don’t want it to look like a Best Buy in here,” said Zurrer.

Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

Each work represents a chapter in a fantasy world that Spratt dreamed up. Though there’s no book of lore to refer to, there seems to be some Planet of the Apes story at play in which an intelligent ape lives alongside humans, babies, and ape-human hybrids. Spratt received an education in oil painting at Savannah College of Art and Design and he credits that technical training with his ability to bring warmth and detail to the digital works. He and the team often say that his art historical references harken to Renaissance and Baroque art, though the aesthetics—to my eye—seem to pull from commercial illustration and concept art. That isn’t too surprising given that this was the environment that Spratt started off in after graduating SCAD in 2010.

“After school I was confronted with the reality that for a digital artist the only path was commercial,” Spratt said.

He did quite well on that path, producing album covers for Childish Gambino, Janelle Monae, and Kid Cudi and bagging clients like Marvel, StreetEasy, and Netflix. Spratt also enjoys a huge audience of fans who have followed him as he’s migrated from Facebook to Tumblr to Twitter and Instagram, posting his hyper-realistic fan-art on each platform. Despite the apparent success, Spratt spoke of the work with bitterness.

“I was a gun for hire. A mimic, hired to be 30% me and 70% someone else,” he said.

Spratt’s personal life blew up when he turned 30 and he traced some of the mistakes he made in his relationships with the fact that he had spent so much of his career “telling other people’s stories.” NFTs seemed like a way out of commercial illustration and a way into an original art practice.

For his latest piece in the LUCI series, Spratt digitally painted a massive landscape set in this ape-human world titled The Monument Game. For the piece, Spratt initially sold NFTs that would turn 209 collectors into “players” (since another edition of 256 NFTs was given to the Council to “curate” new champions”). Each player would then be allowed to make an observation about the painting. The Council of Luci would vote on which three observations were best, and those three Players would receive one of the Skulls of Luci NFTs that Spratt held back. By creating these tiers of engagement, with his Council and player structure, Spratt pushes digital collectors to give the kind of care to his work that more traditional collectors do.

A work at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

“Jeff Koons said that the average person looks at a work of art for twenty seconds,” Lukas Amacher, 1OF1’s Artistic Director and the curator of the show, told ARTnews. “Sam has found a way to get people to engage in his work for much longer.”

The game Spratt has designed for the Venice exhibition might seem too gamified to fit the art world’s notion of art, but as Amacher and Zurrer suggest, in the Web3 environment, value is built by finding alternative ways to create investment and attention in what are typically immaterial digital artifacts. And it’s working. Thus far, the LUCI series has generated $2 million in primary sales and about $4 million in additional secondary volume. The challenge now, as it has been for the past three years, is to see if art’s gatekeepers will take this work seriously.

At the presentation of The Monument Game in Venice, an observation deck, built by platform Nifty Gateway, sits in front of the mounted work. Participants can click on the painting on the screen and write down their observations of the work in front of them, no NFT required. The first observation came from star curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli and curator of Documenta 15: a tribute to art dealer Marian Goodman. The second was from Zurrer. Who’s next?

“Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” is on view until June 21 at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Take in improv comedy, art discussions and shows, locally-produced theatre and live instrumental or choral music.

Unseasonable snow this week isn’t slowing the arts down; nor should it hamper the enjoyment of events around town. Get out and take in a variety of comedy shows, art exhibitions and theatre this weekend.

1 — Laugh along with the Soaps

Article content

Saskatoon Soaps Improv Comedy presents We Love the ’90s. Return to the 1990s improv-style, complete with flannel, grunge and gangsta rap jokes coming faster than the old dial-up internet connection. The troupe performs live comedy based on audience suggestions, so be prepared with your classic references and ideas. The all-ages show is Friday at the Broadway Theatre at 8 p.m. Learn more at broadwaytheatre.ca.

Advertisement 2

Article content

2 — Chat with a local artist and take in an exhibition

The Ukrainian Museum of Canada presents an artist talk by its second artist in residence, Amalie Atkins. The Saskatoon-based artist discusses her residency and how her creative expression resonates with the history of Ukrainian heritage. The free event is Saturday at the museum at 3 p.m. Atkins’s exhibition will be on display through May 18. Learn more at umcnational.ca.

GlassArt showcases glasswork by members of the Saskatoon Glassworkers Guild. The annual show features unique works made through a variety of processes and techniques. Artists are in attendance and there will be some demonstrations. The exhibition runs Friday through Sunday in the Galleria at Innovation Place. Learn more at saskatoonglassworkersguild.org.

3 — Experience live, local theatre

Live Five Independent Theatre presents Bat Brains (or let’s explore mental illness with vampires), a new comedy by Sam Kruger and S.E. Grummett. Inspired by a months-long mental breakdown, the dark comedy follows Scud the vampire, who hasn’t left his house in 53 years. The arrival of an unexpected visitor launches Scud on a journey through his home, his mind and beyond. The show opens Friday and runs to April 28 at The Refinery. Learn more at ontheboards.ca.

Advertisement 3

Article content

4 — Sing along with a local choir

The Saskatoon Men’s Chorus presents the spring concert, Meetin’ Here Tonight. Enjoy gospel and classic favourites with special guests: bassist Bruce Wilkinson, baritone Adam Brookman and the Outlook Men’s Chorus. Sunday at Zion Lutheran Church at 2:30 p.m. Learn more at saskatoonmenschorus.ca.

Cecilian Singers present their spring concert, Come Sing with Me. The singers are joined by three guests: soprano Kelsey Ronn, violinist Wagner Barbosa and percussionist Darrell Bueckert. The concert is Sunday at Grosvenor Park United Church at 3 p.m. Learn more at ceciliansingers.ca.

5 — Listen to historic instruments

The University of Saskatchewan presents Rawlins Piano Trio, the final concert of the season in the Discovering the Amatis series. The chamber music performance features violinist Ioana Galu and cellist Sonja Kraus from the piano trio. They are joined by flutist Joey Zhuang and violinist Véronique Mathieu. Showcasing the historic Amati string instruments, the concert is Sunday at 3 p.m. in Convocation Hall at the U of S. Learn more at leadership.usask.ca.

Recommended from Editorial

With some online platforms blocking access to the news upon which you depend, our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark thestarphoenix.com and sign up for our newsletters here so we can keep you informed.

Article content

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

Benjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

Type 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

Comments