Art

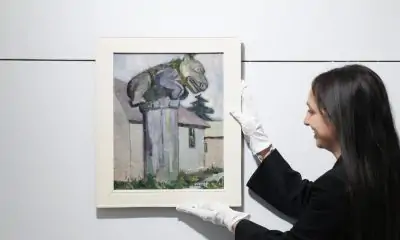

From blasphemous to blessed: Pope’s Venice visit will spotlight Corita Kent’s art

In the 1960s, the Catholic cardinal of Los Angeles labeled the art of Corita Kent as blasphemous. But on Sunday, April 28, it will be given the spotlight by Pope Francis in a Vatican-organized exhibition elevating work that chronicles those on the margins.

Francis will make a half-day trip from Rome to Venice this weekend, becoming the first pope to ever visit the city’s famed art Biennale. When his helicopter touches down, it will land at Giudecca women’s detention center — a 13th-century location that’s not exactly atypical for a pope that has prioritized prison ministry during his 11-year papacy.

But what will be unusual is that the active prison is home to the Holy See’s Biennale pavilion, and the inmates serve as tour guides for the exhibition, including when the visitor is the leader of the Catholic Church.

Under the title of “With My Eyes,” the exhibition utilizes the prison’s chapel, cafeteria and other corridors to display the work of about ten renowned artists whose work in various ways highlight various themes and priorities of the Francis papacy — forcing visitors to go beyond their comfort zones and see realities of those that are often overlooked or neglected.

Among those artists is the work of Corita, as she is affectionately remembered.

Born in 1918, Frances Elizabeth Kent entered the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at age 18, where, as Sr. Mary Corita Kent, she would eventually go on to run the art department at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles.

With bright colors and a bold aesthetic that utilized screenprint to champion messages of social justice, Corita went on to become one of the most important pop art figures of the 20th century.

According to Nellie Scott, executive director of the Corita Art Center, Corita’s art helps to demonstrate that “the uncommon can be found in the common and the ordinary can be extraordinary.”

When I first spoke with Scott on April 16, she had stepped outside of the women’s prison in Venice in order to call me. She was inside preparing for the exhibition’s opening, but it being an operative facility, no cellphones were allowed inside — even for organizers.

Scott said the Corita Art Center was contacted towards the end of 2023 about the possibility of including Corita’s work in the Holy See’s Biennale pavilion. She was immediately enthusiastic about the possibility, not just to have the work shown in such a high-profile environment, but to participate in a project that emphasizes the art of encounter and the chance to interact with the women prisoners as part of the project.

Along with displaying some 20 pieces of Corita’s artwork in the pavilion, the Corita Art Center is partnering with the prison on several educational initiatives for the female inmates, in the spirit of their artist-educator-social justice advocate namesake.

“The call to meet people where they are at is very Corita-like,” said Scott. “And you see that in the works on display in the pavilion.”

During Corita’s lifetime, however, that wasn’t always appreciated.

The Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary had fully embraced the Second Vatican Council’s call to be open and immersed in the world in which they live and had become known for their work among the poor, anti-war activism, and support for civil rights and other prominent social causes of the day.

Messages of love, tolerance and peace are central themes in Corita’s artwork, which quickly rose in popularity throughout the country. But in the city of Los Angeles, Cardinal James Francis McIntyre viewed some of the sisters’ activities as sympathizing with communists and had a special distaste for Corita.

After tangling with the archdiocese for several years, she sought a dispensation from her vows in 1968. That didn’t stop her from continuing to produce art and keep the faith in her own way, until her early death from cancer in 1986 at age 67.

Reflecting on this strange journey of having gone from someone who clashed with church hierarchy to now being given a place of honor in a Vatican-backed exhibition, Scott said that “it’s delightful to see her acknowledged in this way.”

The Biennale, she said, is “not just an opportunity to share the message within her work that certainly fits within this exhibition, but also within the current leadership of the church.”

Included in Corita’s prolific portfolio of work is a colorful screenprint of Pope John XXIII — the pope who opened the Second Vatican Council and ushered in a new era of church reform — with the text: “Let the sun shine in.”

Now, some 60 years later, as Francis opens the Biennale — home to a location and people often closed off from the world — another reforming pope has fittingly chosen the artwork of Corita to help do just that.

Art

Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

- Duct-taped banana artwork auctioned for $6.2m in New York BBC.com

- A duct-taped banana sells for $6.2 million at an art auction NPR

- Is this banana duct-taped to a wall really worth $6.2 million US? Somebody thought so CBC.ca

Art

40 Random Bits of Trivia About Artists and the Artsy Art That They Articulate – Cracked.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

40 Random Bits of Trivia About Artists and the Artsy Art That They Articulate Cracked.com

Source link

Art

John Little, whose paintings showed the raw side of Montreal, dies at 96 – CBC.ca

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

John Little, whose paintings showed the raw side of Montreal, dies at 96 CBC.ca

Source link

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoEstate sale Emily Carr painting bought for US$50 nets C$290,000 at Toronto auction

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoCanada’s Hadwin enters RSM Classic to try new swing before end of PGA Tour season

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoAll premiers aligned on push for Canada to have bilateral trade deal with U.S.: Ford

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoComcast to spin off cable networks that were once the entertainment giant’s star performers

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoClass action lawsuit on AI-related discrimination reaches final settlement

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoTrump nominates former congressman Pete Hoekstra as ambassador to Canada

-

News16 hours ago

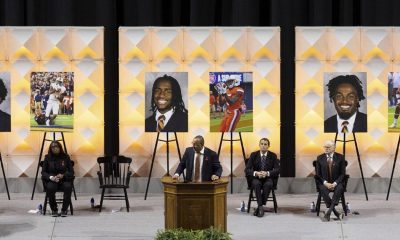

News16 hours agoEx-student pleads guilty to fatally shooting 3 University of Virginia football players in 2022

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoFormer PM Stephen Harper appointed to oversee Alberta’s $160B AIMCo fund manager