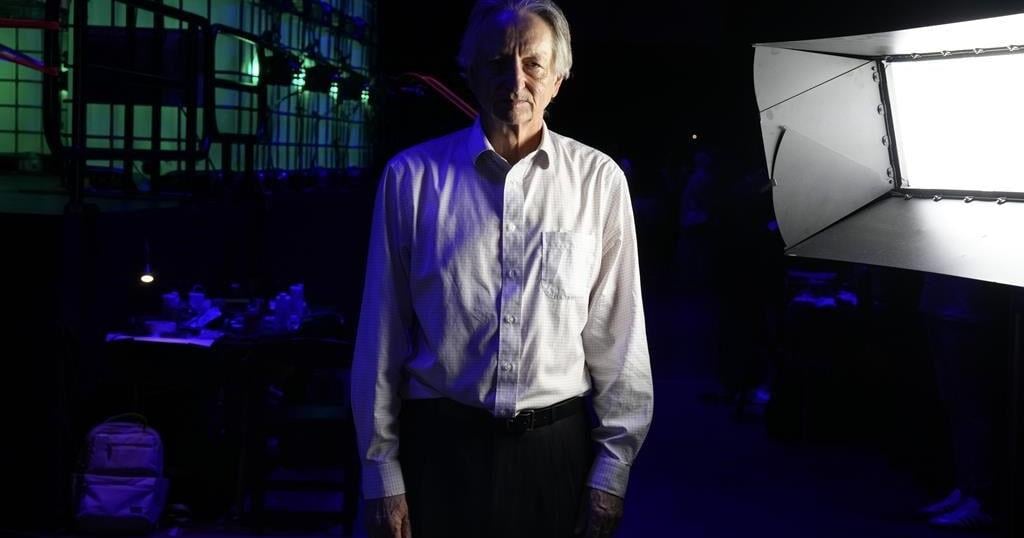

TORONTO – The research that won Geoffrey Hinton a Nobel Prize for physics was the product of plenty of work carried out before artificial intelligence was the buzzword it is today.

The British-Canadian computer scientist and other AI pioneers say his now-celebrated discoveries dating back to the 1980s attracted doubters and a fraction of the attention AI sees today.

“It was a lot of fun doing the research but it was slightly annoying that many people — in fact, most people in the field of AI — said that neural networks would never work,” Hinton recalled during a Tuesday evening press conference to discuss the Nobel honour he was given that morning.

Neural networks are models that mimic the human brain by recognizing patterns and making decisions based on data.

Hinton, a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, was awarded the Nobel Prize for uncovering a method that independently discovers properties in data and is seen as foundational for the large neural networks AI relies on.

His co-laureate John Hopfield, a Princeton University researcher, was honoured for advancing AI by creating a key structure that can store and reconstruct information.

In the heyday of their research, Hinton remembers there being plenty of skeptics.

“They were very confident that these things were just a waste of time and we would never be able to learn complicated things like, for example, understanding natural language using neural networks and they were wrong.”

Hinton persevered, continuing his research even when the scientific community was staring down so-called “AI winters,” said Elissa Strome, executive director of Pan-Canadian AI strategy at the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. (Hinton became involved with the organization in 1987 and remains an advisor.)

AI winters are quiet periods, when interest, development and funding for research around the technology has typically slowed.

“We had a couple of those where the hype of AI wasn’t really being lived up to with the science,” Strome said.

Yoshua Bengio, a fellow Canadian computer scientist who won the A.M. Turing Award with Hinton and French-American Yan LeCun in 2018, said it took about two decades for the perception of neural networks to shift.

The wait wasn’t easy for Hinton.

“He was frustrated that his ideas were kind of rejected by the mainstream,” Bengio said in an interview.

He thinks it took so long for public perception to swing in favour of Hinton’s work because schools of thought can be really entrenched and difficult to change, even in the scientific community.

“For people who are thinking out of the box and maybe in ways that contradict the accepted beliefs, it could be a challenge and it has been for him and it has been for me,” Bengio said.

While accolades have since flowed in for Hinton, Strome said one of the most pivotal moments for his research came on Sept. 30, 2012, when he and a group of researchers won the ImageNet computer vision competition.

The contest centred around a massive database of images. Entrants were challenged to find a machine learning algorithm able to correctly identify each image.

Hinton’s team entered with technology they called AlexNet after one of the members, Alex Krizhevsky.

“They blew all the other sort of older ways of doing machine learning out of the water,” Strome said, creating a “monumental moment.”

A year later, Hinton, Krizhevsky and their teammate and eventual OpenAI co-founder Ilya Sutskever sold their neural network startup DNNresearch Inc. to Google.

Hinton now has an almost-celebrity like status among the technology community that was only bolstered by his Nobel win. On recent visits to tech conferences in Toronto, there’s never an empty seat in the room and the talks he gives generate regular headlines.

Strome sees Hinton’s Nobel win, which even the computer scientist was surprised by, as a reminder that “the next breakthroughs are somewhere on the horizon but we don’t always know what they’re going to be.”

These days, much of the hype around AI has been linked back to U.S. tech company OpenAI launching AI chatbot ChatGPT in November 2022. The release prompted a flood of global companies to get serious about AI and release more products and services embedded with the technology.

At 76, Hinton said he doesn’t plan to do much more “frontier research” and will send his half of the 11 million Swedish kronor (about C$1.45 million) Nobel Prize to charity.

“I believe I’m going to spend my time advocating for people to work on safety,” he said.

Hinton, who quit a job at Google last year to speak more freely about AI, has said he fears the technology could cause misinformation, bias, battle robots, unemployment and even the end of humanity, if safety measures are not deployed.

But he still sees massive potential in AI and, hours after his Nobel win, had a message for the next generation of researchers who might be facing doubters like he did.

“If you believe in something, don’t give up on it until you understand why that belief is wrong,” he said.

“So long as you believe in that, keep working on it and don’t let people tell you it’s nonsense, if you can’t see why it’s nonsense.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 9, 2024.