Art

Have art prizes had their day – Apollo Magazine

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

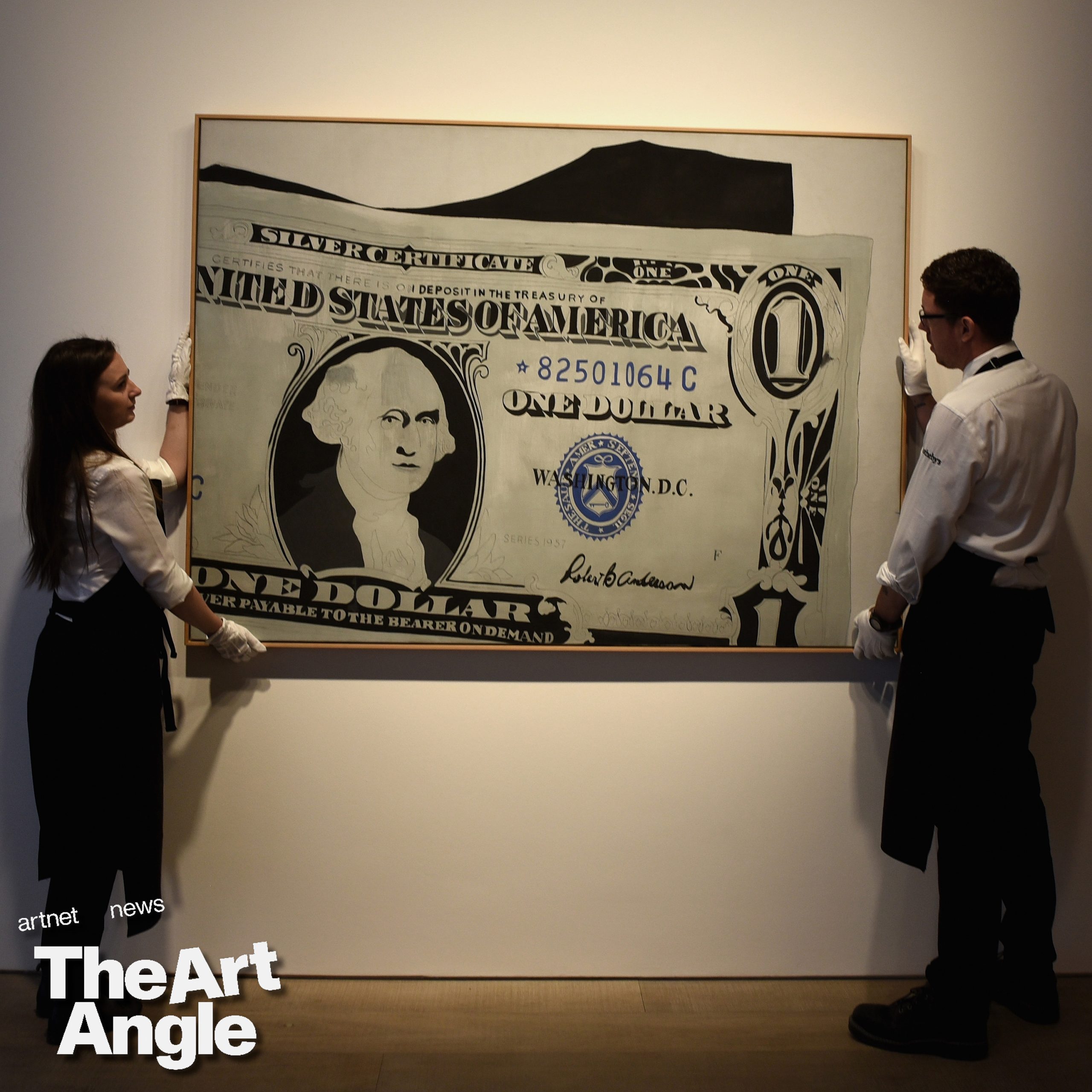

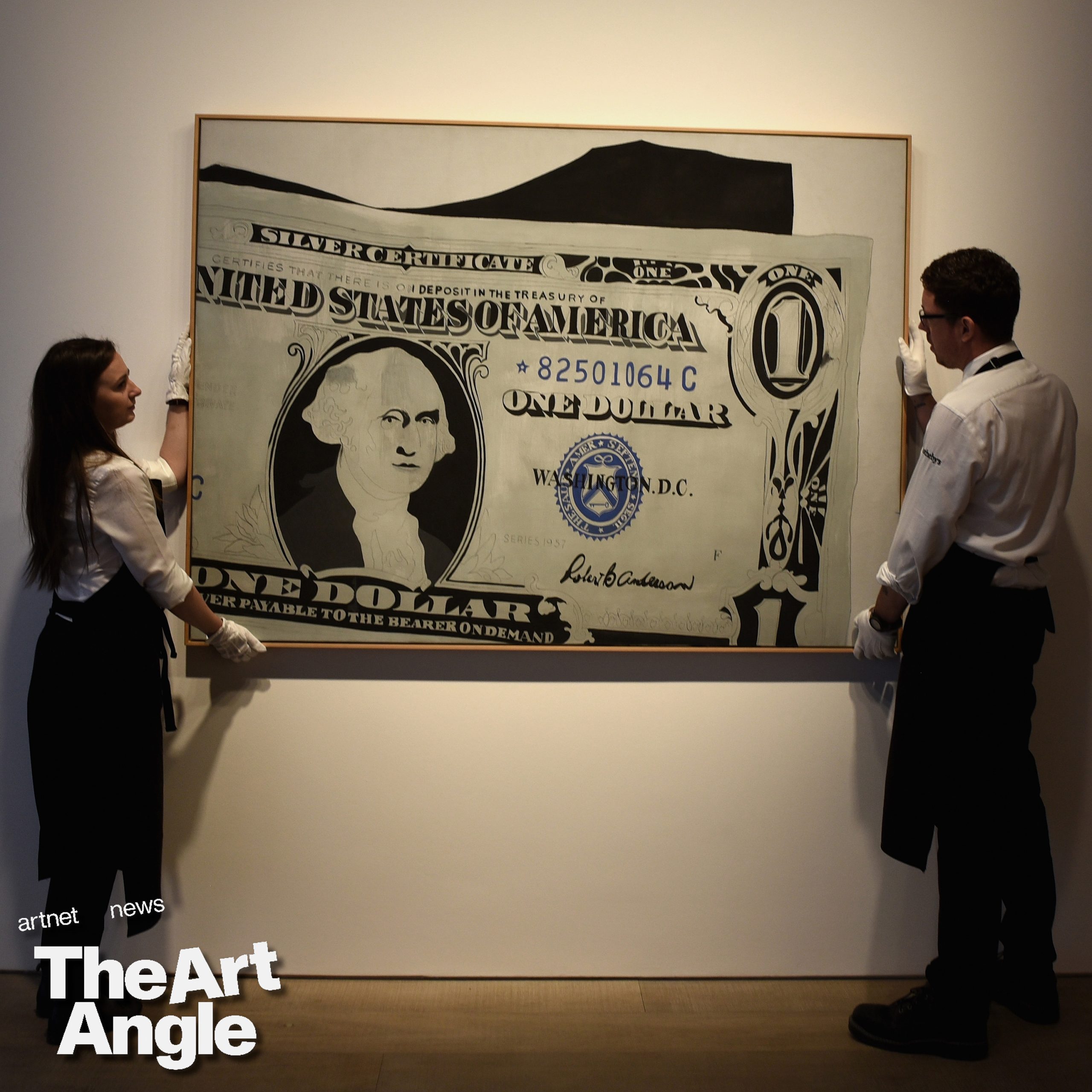

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media10 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media12 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment11 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Business23 hours ago

A sunken boat dream has left a bad taste in this Tim Hortons customer's mouth – CBC.ca

-

News22 hours ago

Best in Canada: Jets Beat Canucks to Finish Season as Top Canadian Club – The Hockey News

-

News21 hours ago

Ontario Legislature keffiyeh ban remains, though Ford and opposition leaders ask for reversal – CBC.ca

-

Health24 hours ago

Health24 hours agoCancer Awareness Month – Métis Nation of Alberta

-

Sports15 hours ago

Sports15 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

24 February 2020

Illustration: David Biskup

The decision to split the 2019 Turner Prize between the four shortlisted artists has divided critics. Do such subversive gestures divest prizes of their power, or open up new ways of judging contemporary art?

Harry Thorne

No prize is an honour,’ wrote Thomas Bernhard, ‘the honour is perverse.’ In My Prizes: An Accounting (2010), a collection of the author’s musings on his relationship to, and vast collection of, literary awards, he spits bile at ‘so-called’ cultural prizes and the ‘feeble-witted’ judges who preside over them; at the ‘vanity, self-prettying and hypocrisy’ of it all.

Which is to say, the hypocrisy in which he himself became embroiled: ‘I remained too weak in all the years that prizes came my way, to say No. […] I despised the people who were giving the prizes but I didn’t strictly refuse the prizes themselves. It was all offensive, but I found myself the most offensive of all.’

Cultural awards are contradictory by nature. They can be era-defining, career-defining, canonising (for better or worse – often worse), yet they are broadly acknowledged to be false indicators of accomplishment. Whether or not we agree with the results, can we accept that ‘merit’, ‘quality’ and ‘achievement’ can be evaluated against a designed criteria? Or, more crucially, should we?

Such questions are enduring. In 1964, Jean-Paul Sartre explained his rejection of the Nobel Prize in Literature with the comment: ‘The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution.’ In recent years, however, these questions have grown louder and more frequent, with creative figures pushing back against the institutions attempting to recognise their work – or, more accurately, against the processes being employed to do so.

In 2019, the Booker Prize twisted its own rules to celebrate two novels, by Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo, a controversial decision that saw detractors note how the first black woman to win the prestigious award had been forced to share it. That same year, the four artists shortlisted for the Turner Prize (Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani) announced that they would only accept the award as a collective. ‘We feel strongly motivated to […] make a collective statement in the name of commonality, multiplicity and solidarity,’ read Cammock at the presentation ceremony, ‘in art as in society.’

Cammock clarified: ‘If there’s any kind of concerns that we’re somehow undermining the prize, it’s exactly the opposite.’ But undermined it has been. As with the numerous high-profile artists who have chosen to share their awards of late, the Turner Prize verdict (or the judges’ immediate acceptance of it) is indicative of a power shift. Faith in prestigious cultural institutions is wavering. In and of itself, this is no bad thing: institutions should push, and be pushed, to faithfully reflect the communities that they represent and, as such, their systems of evaluation should repeatedly be called into question. But the suggestion that the accepting of an award amounts to an endorsement of societal inequality sets a worrying precedent.

For the likes of Murillo and Abu Hamdan, the latter of whom was awarded the Edvard Munch Prize days after the Turner Prize announcement, the exchanging of capital proper for cultural capital might make financial sense, given the market value of their work. For others, however, the monetary value of an award (the Turner prize comes with £25,000) might prove far more beneficial than the figurative pats on the back that they might receive were they to publicly denounce said award. But denounce they might, because, were they not to do so, they would be indirectly opposing ‘commonality, multiplicity and solidarity’.

There are additional considerations when thinking about the opportunities awards create. What of the few prizes that recognise early-career artists (New Contemporaries), regional arts organisations (Museum of the Year), mid-career women artists (the Freelands Award) or ambitious video projects (Jerwood/FVU Awards)? But our changing attitude towards art awards also signals a more abstract threat: a crisis of criticism.

To declare that certain bodies of work are exempt from judgement is to deny that culture, as a whole, is built upon judgement. When we interact with art, literature, or music, for example, we assess it in relation to all that we have experienced before. To assert that, out of respect for an art form’s subject or intent, it is excused from subjective critical evaluation is to reject that truth and delegitimise criticism as a practice.

If, as Cammock suggested, art is bound to society, then so too is judgement. In our contemporary age, cursed as it is, we must strive to protect both – however perverse they might seem.

Harry Thorne is a writer, editor and critic based in London.

Alistair Hudson

The Turner Prize is firmly established as the principal prize in the art calendar and is fully engrained in the public psyche. It has regularly introduced the general public to the current state of contemporary art, facilitated by an association perfected over the years between media and institution. The success of the prize has come in part from its capacity to shock: an unmade bed, a potter not a painter, architects not artists, a pickled calf or a bum-hole doorway.

Last year in Margate the shock came not from the art but the announcement itself. Artists Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock, Oscar Murillo and Tai Shani chose to share the prize ‘to make a collective statement in the name of commonality, multiplicity and solidarity – in art as in society’. The statement drew a standing ovation and seemed genuinely moving; in a time of division here was some unity. The gesture offered a challenge to the prize, or at least its integrity as a competitive sport.

Cue the ensuing debate. For some, this act of selflessness would change the prize for good, even bring it to an end, now that artists had unionised in this way. This might be the case, but I suspect not. An artist I was chatting with not long after confirmed that if they were nominated, they would not be sharing the prize with anyone.

My own jury service for the Turner Prize was in 2015 and resulted in the Assemble collective winning for their regeneration project with residents of the Granby Four Streets neighbourhood in Liverpool. The idea of a multidisciplinary group working outside the art market, or even something ‘not art at all’ triumphing, was seen then as a big challenge to the system. That other art worlds exist was not easy to digest. ‘You’ve broken art!’ someone said on the night. I reassured them that it would be business as usual next year, and it was.

The Turner’s resilience suggests that such art prizes still have a role to play, as long as we live in an age of spectacle. However, they belong to a time that is passing, one rooted in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the ‘exhibitionary’ moment. The emerging shift from mechanistic thinking to ecological thinking – or our habit of thinking about art in isolation from the world rather than as something that is connected to wider cultural or social frameworks – will bring with it a change in emphasis from product to process. We are already seeing the emergence of a more values-driven generation which is in turn driving a more values-based economy. The unionisation of last year’s Turner Prize winners hints at this, in turning the gaze from the prize itself to wider societal issues.

In this context art prizes must evolve so as to support and make visible the process of making art and its effect on the world. Concentrating attention on the singular image or object does not tell the full story of the role that art plays in our culture, reinforcing an idea of creativity complicit with the market rather than enriching a broader social capital. Now is the time to reassert art as a vital process that operates across education, social development, health and the broader economy.

There are some examples of this approach already in play. In recent years, the Artes Mundi prize has worked with the shortlisted artists on long-term commissions and projects in South Wales. The peripatetic Visible Award supports artists, chosen through a quasi-parliamentary public jury process,

to expand and deliver on their socially engaged practices. The point here is to engage with artistic projects that, in a radical and proactive way, are able to rethink our cities or rural communities, question education models and propose alternative models of economic development.

Both these formats exemplify how art prizes can be more open-ended, experimental and creative and less embedded in a singular perception of art as merely complicit in market and spectacle. I would welcome this further dissolution of art into the everyday, and suggest it is a viable approach for thinking about the future of art prizes.

Alistair Hudson is the director of the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery.

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.