Parents running out of paid leave to care for a child with a simple runny nose or sore throat caught a break Thursday when Dr. Deena Hinshaw struck those from the list of core COVID-19 symptoms.

Mirroring updated regulations in B.C., Quebec and Ontario, children in Alberta will no longer have to self-isolate for 10 days or get tested for the virus if they have only a sore throat or runny nose, two symptoms that are more likely to indicate a common childhood cold.

Taking effect Monday, the new requirement sends these children home for 24 hours instead, monitored in case symptoms get worse.

“Runny nose is a very, very common symptom, as is a sore throat, and it’s not very specific for COVID,” Alberta’s chief medical officer of health said in an interview before Thursday’s announcement.

Alberta residents will be coping with COVID-19 restrictions for months, Hinshaw said. This change is part of trying to make that burden as light as possible and gain maximum compliance.

“Measures that are in place that make peoples’ lives more difficult but don’t actually help that much to prevent COVID, we need to lift those when we have the evidence to do so,” she said.

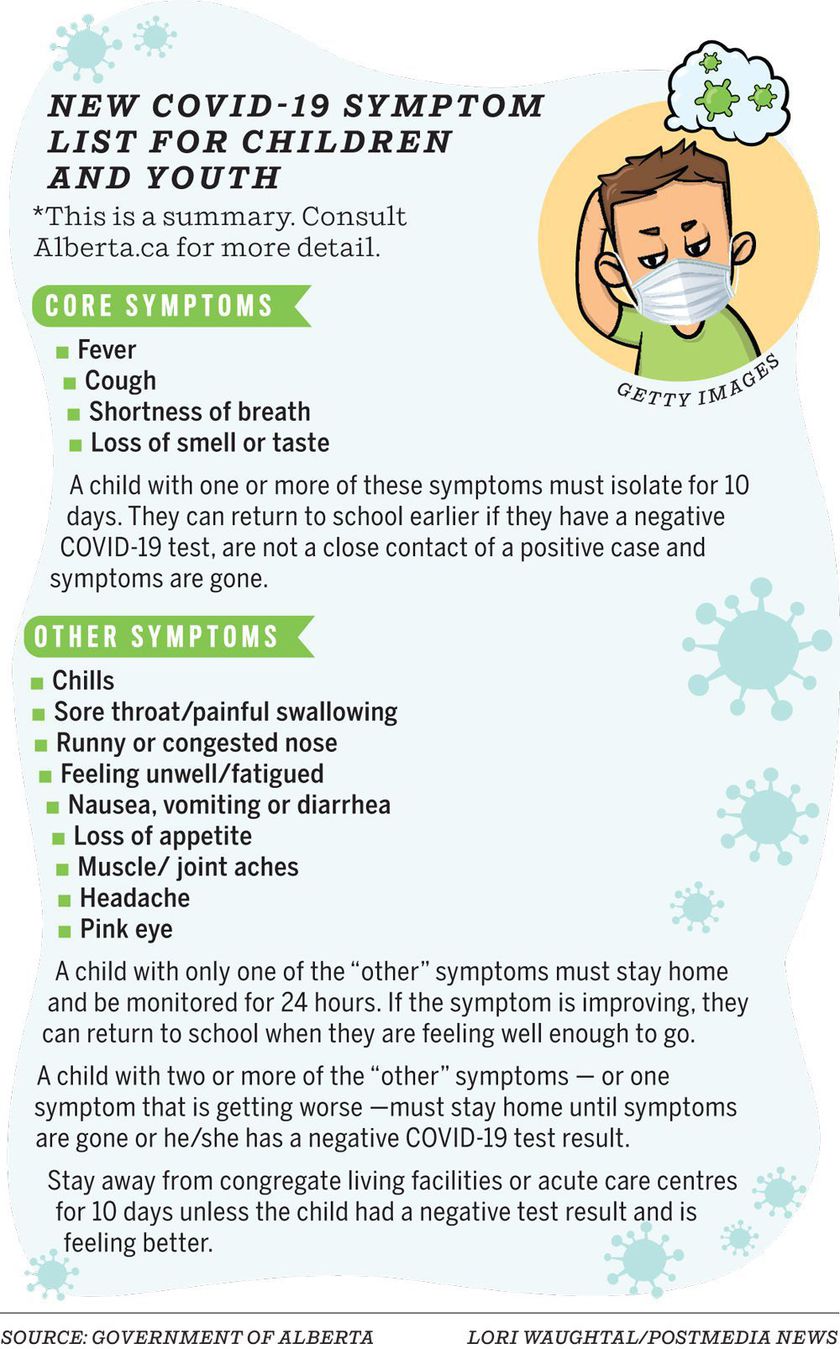

There is still a mandatory 10-day isolation or testing requirement for children with a cough, fever, loss of taste or smell and/or shortness of breath.

Runny nose and sore throat are included in a longer list of secondary symptoms. If a child has one symptom from that list on the Alberta Health website they must stay home for 24 hours to see if the symptom worsens or more symptoms develop. If nothing gets worse, a child may return to school and other children’s activities, even if the symptom hasn’t resolved.

For students with two or more secondary symptoms, testing is still recommended. A child must stay home until symptoms go away or they test negative. The relaxed rules do not apply to adults yet.

Existing rules cause hardship

Many parents had been struggling with the isolation requirements, particularly when schools sent students home for a simple runny nose.

In the Edmonton Journal’s Groundwork engagement project, parents reported having to call in more vulnerable grandparents to help when kids come down with a cold. They’re being forced to call in sick themselves, which creates additional staffing challenges for schools, hospitals and other workplaces.

Isolating a child is really tough when parents have to keep leaving the house to get groceries or bring other children to school, said Laura Shyko in an interview. Her three elementary-school aged children came down with runny noses, testing negative for COVID-19, one after the other.

She didn’t have the heart to drag the last one, a five-year-old, kicking and screaming to get the nasal swab. “It was all so clear she just had a cold,” she said.

By now, parents are running out of paid leave themselves, said Joanna Coleman, who has had to leave work four separate times so far, with three children off school 13 days, for a variety of headaches and colds that tested negative for COVID-19.

At one point, the school sent her daughter home simply because her nose ran for 15 minutes after coming in from the cold. A single mom, she is now out of paid vacation and sick days. “I do understand the need for this,” she said. But anything that can safely streamline the process is appreciated. “We’re not going to be back to normal for a very long time.”

Data driving the change

Hinshaw said Alberta Health feels confident about making this change based on three different data sets — data showing a similar change did not significantly increase transmission in Ontario schools when it was made Oct. 1, symptom descriptions collected since the start of the pandemic after children test positive, and new data from Alberta on the children with a runny nose or sore throat who test negative for COVID-19.

On that last data set, technical challenges meant Alberta Health Services only recently started asking for a full list of symptoms from each person requesting a COVID-19 test online, Hinshaw said.

But in the last week, for example, 3,300 children under 18 said they had a runny nose when they applied for a test. Of those, 600 children had no other symptom. Two of those children then tested positive, and only one of them had no known connection to a positive COVID-19 case.

Under the new rules, only the child with just a runny nose and a close contact must stay home and get tested. The rest of the 600 could simply monitor for symptoms, then head back to school after 24 hours if symptoms didn’t worsen.

Alberta Health is still analyzing this type of data for adults and asked its science advisory panel to help. The current change does not apply to adults because they can have different symptoms, are at a higher risk of getting seriously ill from the disease, and are more likely to pass it on to others.

The risk is not zero

But it’s a difficult subject. The risk is not zero and Alberta has had record numbers of new daily COVID-19 cases lately. Of that group of 600 children with only a runny nose, one child still tested positive and that child would be at school, potentially infectious, under these new rules.

Through the Groundwork surveys and virtual office hours, the Edmonton Journal also heard from parents with children in school who were already anxious about peers not following the daily wellness check recommendations.

Many parents with children studying online say this is because they don’t trust that the in-school environment is safe enough. Some of them have medically-fragile family members to protect, and some wish they could let their children study safely at home but their jobs, children’s needs or the family situation makes that impossible.

“I completely understand that concern,” Hinshaw said, adding that this change is about balance and trying to gain compliance, knowing there will always be some risk at school because of asymptomatic transmission. “We’re not throwing caution to the wind, but saying: How can we make sure people can live with this for several months to come?”