Toronto couple Alan and Alison Schwartz were facing some major transitions as they planned their next home. They were moving out of a series of single-family homes into an apartment for their empty-nester years, and they were rethinking the focus of their extensive art collection. Their challenge was to create a home that was good for their cutting-edge art but comfortable for them. Their strategy? Take it slow, allowing art and décor to merge into a lifestyle.

The couple paid 4.8 million Canadian dollars, or about $3.7 million,…

Toronto couple Alan and

Alison Schwartz

were facing some major transitions as they planned their next home. They were moving out of a series of single-family homes into an apartment for their empty-nester years, and they were rethinking the focus of their extensive art collection. Their challenge was to create a home that was good for their cutting-edge art but comfortable for them. Their strategy? Take it slow, allowing art and décor to merge into a lifestyle.

The couple paid 4.8 million Canadian dollars, or about $3.7 million, in 2011 for two units in a new low-rise residential building in Toronto’s central Yorkville neighborhood. They then went on to spend $600,000 over the next several years to combine the two apartments into a 4,200-square-foot duplex with two bedrooms and 2.5 bathrooms. They moved into the finished home in summer 2017, but they went on adjusting and rearranging for three more years, putting key pieces of art in place only this past year.

“Every room now feels right to us,” says Mr. Schwartz, a former financial-services executive, who is managing director of Studio TLA, a landscape architecture and design firm with offices in Toronto and Dallas.

When the couple made their decision to buy based only on the blueprints for the planned project, the developer suggested they combine two units on the same floor. Frequent entertainers, they opted instead for two stacked units, allowing them to save the main bedroom and guest room—and their privacy—for upstairs. Working with Toronto’s Roundabout Studio, the couple then opted for an open-plan downstairs, creating a living room with different seating areas, a formal dining room and a partially hidden kitchen. The two levels are connected by a sleek glass-and-concrete staircase.

Aiming for a subdued background for their art, and a sense of tranquility for themselves, the couple wanted what they called the same palette throughout much of the home, says Mr. Schwartz, which meant repeating materials in different settings. The concrete from the staircase shows up again in the kitchen island and as the living room’s fireplace mantelpiece. Acid-edge patina steel, also used in the fireplace, reappears as the kitchen island’s base and in the downstairs den, where it is used as a retractable panel to hide a television.

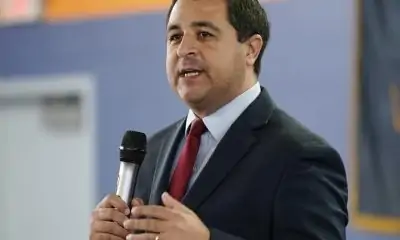

The Schwartzes started collecting art in the 1980s.

Photo: JENNIFER ROBERTS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The new direction in their art collection began around the time of the 2011 purchase of the two units. They started in the 1980s with Canadian art, then turned to international photo-based art in the 1990s, amassing works by figures such as Germany’s Andreas Gursky and Canada’s own Jeff Wall, who have since grown in recognition. Then, in the early 2000s, they changed course, investing more heavily in German painters, such as Martin Kippenberger, now one of the most expensive contemporary artists at auction.

By the time they began planning their new Yorkville home, they had moved on to works by women and artists of color, and their collection now includes pieces by Simone Leigh, the Chicago-born sculptor who will represent the U.S. later this year at the Venice Biennale, and Wangechi Mutu, the Kenya-born American artist.

Unlike many major collectors, who often leave works in storage, the Schwartzes believe in living with their art, donating or selling categories they no longer actively collect. One holdover from their early photo-art phase, a self-portrait of American artist Cindy Sherman, has pride of place on the second floor.

The couple had a few false starts. They initially considered concrete floors, suitable for an art gallery, but decided instead on oiled, wide-plank oak, which suggests barn wood, says Mr. Schwartz, deferring to his wife, a philanthropist. She was worried that their initial plan “was too harsh and institutional,” he adds.

The couple connected the two levels of their combined condos with a glass-and-concrete staircase.

Photo: JENNIFER ROBERTS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The home has a south-facing glass facade, allowing for city views. But all that glass, combined with the open plan, means a stark reduction in areas where art can be exhibited. Roundabout’s design director, Daniel Harland, and his team came up with a solution by adding display areas throughout. Off the dining area, they chose a load-bearing pillar as an anchor for a plastered panel, where the couple now have a 2017 work by Adam Pendleton, a young African-American conceptual artist.

Another display opportunity was created in the living room by extending the fireplace’s hearth, which has become the spot for a work by Ms. Leigh. Another work by the artist—a cobalt-colored, glazed-stone bust purchased just last year—is prominently displayed on the kitchen island’s extension.

The Schwartzes have a talent for anticipating the twists and turns of the art world, and their decision to buy a downtown condo has proven a good investment. Toronto itself is one of the world’s hottest luxury real-estate markets.

In Knight Frank’s most recent Prime Global Cities Index, which tracks urban luxury prices, Toronto saw increases of more than 20% between the third quarters of 2020 and 2021—the world’s fifth strongest, the study says.

Paul Maranger, a Toronto-based sales executive at Sotheby’s International Realty Canada, says new and recent luxury condo complexes like the Schwartzes, especially those in Yorkville, are averaging up to $1,881 a square foot. In a market marked by drastic supply shortages, owners are willing to invest in projects four or five years away from completion, he adds.

The Schwartzes, who frequently visit New York City to look at art, are in Yorkville for the long haul. And while they are still in the same collecting phase, they are prepared for what might come next with an adaptable lighting system, devised by Roundabout, that should be suitable for all types of art. “In a world like ours,” says Mr. Schwartz of his collecting vocation, “things change.”