Economy

How to Save a Half-Open Economy – The New York Times

When states began to order businesses to close and residents to stay home as the coronavirus outbreak spread, economists likened the policy to a medically induced coma: shutting down all but the most vital functions to focus on the underlying affliction.

Now the patient is awake, but the malady remains.

A surge in coronavirus cases has forced several states to reimpose restrictions and dashed hopes of a rapid economic rebound. But a widespread return to the shutdown policies that dominated in March and April seems unlikely.

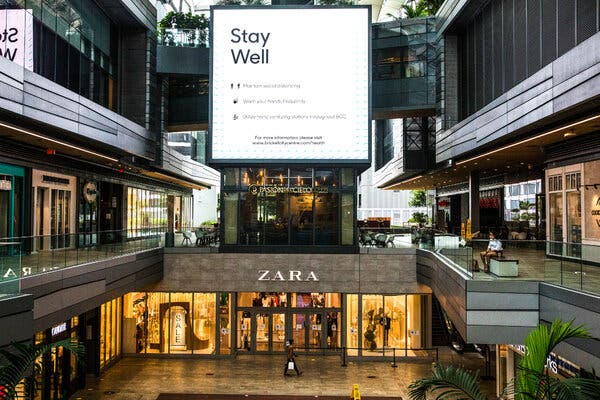

Instead, the economy looks likely to remain in a sort of limbo, neither fully open nor fully shut, for months or even years.

For certain workers in certain industries in certain locations, life again seems somewhat normal. But for many others — those whose age or health conditions make them especially vulnerable to the virus, or who have young children at home, or who work in high-risk industries, or who live in places where cases are rising rapidly — the pandemic remains a major disruption.

This new phase poses a unique challenge for policymakers. Economists across the political spectrum say it would be a mistake for the federal government to cut off support for workers and businesses while the economy remained weak. But those policies may need to be revamped to help the worst-hit industries and regions — and will have to change as the crisis evolves.

“We don’t know how the pandemic is going to unfurl, and we don’t know where the hot spots are going to be,” said Wendy Edelberg, a former chief economist for the Congressional Budget Office and now the director of the Hamilton Project, an economic policy arm of the Brookings Institution. “That’s going to demand that the policy response be a lot more nimble.”

Still, economists and other experts say there are steps that government, at all levels, can take to mitigate the economic damage.

Prioritize public health.

In the political debate over reopening, economic and public health considerations are often portrayed as being at odds. But economists have said since the beginning of the crisis that the two go hand in hand: The economy cannot recover until the virus is in check.

“One thing we’ve learned thus far is that a halfway commitment to public health measures just isn’t very effective,” said David Wilcox, a former Federal Reserve official who is an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “It’s not effective in arresting the virus, and you still incur tremendous economic damage. In order to build the foundation of a secure recovery, the imperative is to bring the virus under control.”

#styln-briefing-block

font-family: nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;

background-color: #F3F3F3;

padding: 20px;

margin: 37px auto;

border-radius: 5px;

color: #121212;

box-sizing: border-box;

width: calc(100% – 40px);

#styln-briefing-block a

color: #121212;

#styln-briefing-block a.briefing-block-link

color: #121212;

border-bottom: 1px solid #cccccc;

font-size: 0.9375rem;

line-height: 1.375rem;

#styln-briefing-block a.briefing-block-link:hover

border-bottom: none;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-bullet::before

content: ‘•’;

margin-right: 7px;

color: #333;

font-size: 12px;

margin-left: -13px;

top: -2px;

position: relative;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-bullet:not(:last-child)

margin-bottom: 0.75em;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-header-section

margin-bottom: 16px;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-header

font-weight: 700;

font-size: 16px;

line-height: 20px;

display: inline-block;

margin-right: 6px;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-header a

text-decoration: none;

color: #333;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-footer

font-size: 14px;

margin-top: 1.25em;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-briefinglinks

padding-top: 1em;

margin-top: 1.75em;

border-top: 1px solid #E2E2E3;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-briefinglinks a

font-weight: bold;

margin-right: 6px;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-footer a

border-bottom: 1px solid #ccc;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-footer a:hover

border-bottom: 1px solid transparent;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-header

border-bottom: none;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-lb-items

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: auto 1fr;

grid-column-gap: 20px;

grid-row-gap: 15px;

line-height: 1.2;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-update-time a

color: #999;

font-size: 12px;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-update-time.active a

color: #D0021B;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-footer-meta

display: flex;

justify-content: space-between;

align-items: center;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-ts

color: #D0021B;

font-size: 11px;

display: inline-block;

@media only screen and (min-width: 600px)

#styln-briefing-block

padding: 30px;

width: calc(100% – 40px);

max-width: 600px;

#styln-briefing-block a.briefing-block-link

font-size: 1.0625rem;

line-height: 1.5rem;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-bullet::before

content: ‘•’;

margin-right: 10px;

color: #333;

font-size: 12px;

margin-left: -15px;

top: -2px;

position: relative;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-header

font-size: 17px;

#styln-briefing-block .briefing-block-update-time a

font-size: 13px;

@media only screen and (min-width: 1024px)

#styln-briefing-block

width: 100%;

If political leaders want businesses to reopen and customers to return, Mr. Wilcox said, they need to invest in widespread testing and tracing to make consumers confident that they are safe. And they need to avoid encouraging businesses to reopen before it is safe to do so.

Extend unemployment benefits.

More than 20 million Americans are getting an extra $600 a week in their unemployment checks because of the federal aid package passed in March, but that provision is scheduled to expire this month. While some economists say the enhanced benefits could be scaled back or modified, most say it would be a mistake to let them lapse altogether.

Unemployment benefits are serving three purposes. In states where the virus is raging, they help residents afford to stay home, which is crucial to overcoming the pandemic. In all states, they help jobless workers avoid hunger, eviction and financial ruin. And by providing billions of dollars to the people most likely to spend it, they stimulate the economy.

The extra $600 means that many low-wage workers are earning more on unemployment than they were on the job, which Republicans in Congress worry could discourage returning to work. Economists say that is a valid concern — when the unemployment rate is low and workers are scarce. Right now, the situation is the opposite: In May, there were roughly five million open jobs and 20 million unemployed workers.

“There’s not enough jobs for everybody anyway,” said Erik Hurst, an economist at the University of Chicago who has been studying the economic effects of the pandemic.

Some economists, particularly on the right, say it may make sense to reduce the weekly supplement as the economy improves, and some have suggested tweaks like a “back-to-work bonus” that rewards people for finding jobs. But few think it makes sense to scrap the enhanced benefits.

Spend what it takes to reopen schools safely.

Whether or not to reopen schools this fall has become a political point of contention in recent days. But economists say there is no doubt about one thing: The economy can’t get back to normal while millions who would otherwise be working must stay at home caring for their school-age children.

Epidemiologists and public health experts are unsure that in-person classes can be held safely in places where the virus is out of control, like Florida and Arizona. But in other places, the biggest obstacle is money: It would cost billions of dollars to retrofit classrooms, overhaul ventilation systems, buy protective equipment and add staff members to ensure that both children and adults were safe.

“Schools are going to need a lot more resources to get open safely, given we haven’t gotten the virus under control in a lot of places,” said Melissa Kearney, a University of Maryland economist who heads the Economic Strategy Group at the Aspen Institute. “The less control we have over this virus, the more expensive it’s going to be.”

State and local governments, reeling from plummeting tax revenues, don’t have the resources for such changes. But the federal government does. And it could be money well spent: Allowing schools to reopen safely would free up adults for work and allow other economic activity to resume.

Keep businesses alive.

Even in states where the virus is less prevalent, some businesses, like indoor bars, movie theaters and concert venues, may not be able to open safely for a long time. Others, like restaurants, will have to operate at a capacity unlikely to turn a profit.

That means that without government help, thousands of businesses are likely to fail in the months ahead. That could have devastating economic consequences, turning temporary furloughs into permanent job losses and slowing the eventual recovery.

Lost jobs “are going to come back very slowly — it’s going to be months and months of hard work,” said Betsey Stevenson, a University of Michigan economist who was on President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. “The question is, do we have 30 million people who are going to go through that process, or do we have five million? We don’t have the answer to that yet, but every month it goes on, that number grows larger.”

Experts say Congress needs a new approach to save businesses.

The Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think tank focused on entrepreneurship, has proposed giving interest-free loans to small employers. Rather than providing a temporary injection of cash, they argued, a loan program could let companies invest in improving their long-term prospects. A retailer could buy a building it had been renting, for example, bringing down monthly costs. Or a restaurant could add outdoor space, reducing dependence on indoor dining.

Mr. Wilcox of the Peterson Institute has recommended a more expansive — and expensive — approach, essentially having the government fill in the revenue shortfall created by the pandemic through direct grants to businesses. The government has effectively forced business owners to take a hit, he said, so it should help them survive.

“Start from a social agreement that the government is going to take onto its shoulders the cost of sustaining businesses through the period of intense public health crisis,” he said.

Provide some certainty.

No one knows where and when cases will surge, how long the pandemic will last, or when a vaccine will be ready. That makes it harder for both businesses and policymakers to plan effectively, said Martha Gimbel, an economist and a labor market expert at Schmidt Futures, a philanthropic initiative.

“If we knew we were going to have a vaccine in January, we could make decisions,” she said. “If we knew we were going to have a vaccine in January 2022, we could make decisions. But we don’t know, and economies don’t do well when there’s uncertainty.”

Economic policy can’t eliminate that uncertainty. But right now, it is making it worse: Jobless workers don’t know whether their extra benefits will run out in a matter of days. Businesses don’t know if they will be able to apply for a new round of federal loans, or have to enroll in a new program, or get nothing at all. State and local governments are trying to plug multibillion-dollar budget holes with no idea whether they will get federal help, or how much.

Economists have urged Congress to answer some of those questions — not just now, but for the future. Benefits could be linked to the unemployment rate, for example, so that workers would not have to worry about losing benefits before the job market improved. Similar steps, linked to different metrics, could make businesses and state and local governments confident that government support won’t evaporate without warning.

Brinkmanship, on the other hand, could have economic costs even if Congress ends up extending support at the last moment.

Economy

U.S. economic growth slowed more than expected in first quarter

|

|

The U.S. economy grew at its slowest pace in nearly two years as a jump in imports to meet still-strong consumer spending widened the trade deficit, but an acceleration in inflation reinforced expectations that the Federal Reserve would not cut interest rates before September.

The slowdown in growth reported by the Commerce Department in a snapshot of first-quarter gross domestic product on Thursday also reflected a slower pace of inventory accumulation by businesses and downshift in government spending. Domestic demand remained strong last quarter.

“This report comes in with mixed messages,” said Olu Sonola, head of economic research at Fitch. “If growth continues to slowly decelerate, but inflation strongly takes off again in the wrong direction, the expectation of a Fed interest rate cut in 2024 is starting to look increasingly more out of reach.”

Gross domestic product increased at a 1.6 per cent annualized rate last quarter, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis said. Growth was largely supported by consumer spending. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast GDP rising at a 2.4 per cent rate, with estimates ranging from a 1.0 per cent pace to a 3.1 per cent rate.

The economy grew at a 3.4 per cent rate in the fourth quarter. The first quarter growth’s pace was below what U.S. central bank officials regard as the non-inflationary growth rate of 1.8 per cent.

Inflation surged, with the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index excluding food and energy increasing at a 3.7 per cent rate after rising at 2.0 per cent pace in the fourth quarter.

The so-called core PCE price index is one of the inflation measures tracked by the Fed for its 2 per cent target. The central bank has kept its policy rate in the 5.25 per cent-5.50 per cent range since July. It has raised the benchmark overnight interest rate by 525 basis points since March of 2022.

Consumer spending grew at a still-solid 2.5 per cent rate, slowing from the 3.3 per cent growth pace rate notched in the fourth quarter.

Economists worry that lower-income households have depleted their pandemic savings and are largely relying on debt to fund purchases. Recent data and comments from bank executives indicated that lower-income borrowers were increasingly struggling to keep up with their loan payments.

Business inventories increased at a $35.4-billion rate after rising at a $54.9-billion pace in the fourth quarter. Inventories subtracted 0.35 percentage point from GDP growth.

The trade deficit chopped off 0.86 percentage point from GDP growth. Excluding inventories, government spending and trade, the economy grew at a 3.1 per cent rate after expanding at a 3.3 per cent rate in the fourth quarter.

Economy

U.S. growth slowed sharply last quarter to 1.6% pace, reflecting an economy pressured by high rates – BNN Bloomberg

WASHINGTON — The U.S. economy slowed sharply last quarter to a 1.6 per cent annual pace in the face of high interest rates, but consumers — the main driver of economic growth — kept spending at a solid pace.

Thursday’s report from the Commerce Department said the gross domestic product — the economy’s total output of goods and services — decelerated in the January-March quarter from its brisk 3.4 per cent growth rate in the final three months of 2023.

A surge in imports, which are subtracted from GDP, reduced first-quarter growth by nearly 1 percentage point. Growth was also held back by businesses reducing their inventories. Both those categories tend to fluctuate sharply from quarter to quarter.

By contrast, the core components of the economy still appear sturdy. Along with households, businesses helped drive the economy last quarter with a strong pace of investment.

The import and inventory numbers can be volatile, so “there is still a lot of positive underlying momentum,” said Paul Ashworth, chief North America economist at Capital Economics.

The economy, though, is still creating price pressures, a continuing source of concern for the Federal Reserve. A measure of inflation in Friday’s report accelerated to a 3.4 per cent annual rate from January through March, up from 1.8 per cent in the last three months of 2023 and the biggest increase in a year. Excluding volatile food and energy prices, so-called core inflation rose at a 3.7 per cent rate, up from 2 per cent in fourth-quarter 2023.

From January through March, consumer spending rose at a 2.5 per cent annual rate, a solid pace though down from a rate of more than 3 per cent in each of the previous two quarters. Americans’ spending on services — everything from movie tickets and restaurant meals to airline fares and doctors’ visits — rose 4 per cent, the fastest such pace since mid-2021.

But they cut back spending on goods such as appliances and furniture. Spending on that category fell 0.1 per cent, the first such drop since the summer of 2022.

The state of the U.S. economy has seized Americans’ attention as the election season has intensified. Although inflation has slowed sharply from a peak of 9.1 per cent in 2022, prices remain well above their pre-pandemic levels.

Republican critics of President Joe Biden have sought to pin responsibility for high prices on Biden and use it as a cudgel to derail his re-election bid. And polls show that despite the healthy job market, a near-record-high stock market and the sharp pullback in inflation, many Americans blame Biden for high prices.

Last quarter’s GDP snapped a streak of six straight quarters of at least 2 per cent annual growth. The 1.6 per cent rate of expansion was also the slowest since the economy actually shrank in the first and second quarters of 2022.

The economy’s gradual slowdown reflects, in large part, the much higher borrowing rates for home and auto loans, credit cards and many business loans that have resulted from the 11 interest rate hikes the Fed imposed in its drive to tame inflation.

Even so, the United States has continued to outpace the rest of the world’s advanced economies. The International Monetary Fund has projected that the world’s largest economy will grow 2.7 per cent for all of 2024, up from 2.5 per cent last year and more than double the growth the IMF expects this year for Germany, France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and Canada.

Businesses have been pouring money into factories, warehouses and other buildings, encouraged by federal incentives to manufacture computer chips and green technology in the United States. On the other hand, their spending on equipment has been weak. And as imports outpace exports, international trade is also thought to have been a drag on the economy’s first-quarter growth.

Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director, cautioned last week that the “flipside″ of strong U.S. economic growth was that it was ”taking longer than expected” for inflation to reach the Fed’s 2 per cent target, although price pressures have sharply slowed from their mid-2022 peak.

Inflation flared up in the spring of 2021 as the economy rebounded with unexpected speed from the COVID-19 recession, causing severe supply shortages. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 made things significantly worse by inflating prices for the energy and grains the world depends on.

The Fed responded by aggressively raising its benchmark rate between March 2022 and July 2023. Despite widespread predictions of a recession, the economy has proved unexpectedly durable. Hiring so far this year is even stronger than it was in 2023. And unemployment has remained below 4 per cent for 26 straight months, the longest such streak since the 1960s.

Inflation, the main source of Americans’ discontent about the economy, has slowed from 9.1 per cent in June 2022 to 3.5 per cent. But progress has stalled lately.

Though the Fed’s policymakers signaled last month that they expect to cut rates three times this year, they have lately signaled that they’re in no hurry to reduce rates in the face of continued inflationary pressure. Now, a majority of Wall Street traders don’t expect them to start until the Fed’s September meeting, according to the CME FedWatch tool.

Economy

Germans Debate Longer Hours and Later Retirement as Economic Growth Falters – Bloomberg

German politicians and business leaders, despairing a weak economy, are lately broaching a once taboo topic: claiming their compatriots don’t work enough. They may have a point.

German Finance Minister Christian Lindner fired the latest salvo in this fractious debate last week when he said that “in Italy, France and elsewhere they work a lot more than we do.” Economy Minister Robert Habeck, a Green Party representative, grumbled in March about workers striking, something a country beset by labor shortages “cannot afford.” (Later that month train drivers secured a 35-hour workweek instead of 38, for the same pay.) Signaling his opposition to a four-day work week, Deutsche Bank AG Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing in January urged Germans “to work more and work harder.”

-

Real eState20 hours ago

Montreal tenant forced to pay his landlord’s taxes offers advice to other renters

-

Media19 hours ago

B.C. online harms bill on hold after deal with social media firms

-

Investment20 hours ago

Investment20 hours agoMOF: Govt to establish high-level facilitation platform to oversee potential, approved strategic investments

-

Politics20 hours ago

Politics20 hours agoPolitics Briefing: Younger demographics not swayed by federal budget benefits targeted at them, poll indicates

-

News19 hours ago

Just bought a used car? There’s a chance it’s stolen, as thieves exploit weakness in vehicle registrations

-

Science19 hours ago

Science19 hours agoGiant prehistoric salmon had tusk-like spikes used for defence, building nests: study

-

Tech19 hours ago

Tech19 hours agoCalgary woman who neglected elderly father spared jail term

-

Real eState18 hours ago

Luxury Real Estate Prices Hit a Record High in the First Quarter