Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

Jason Hunt comes from a long line of renowned First Nations artists whose works and livelihoods are being undermined by fraudulent reproductions of their work

First Nations artists like Jason Henry Hunt—a renowned carver and nephew of legendary North West Coast artist Richard Hunt—spend a lifetime learning the intricacies of their craft. But fraudulent works (most of which are mass-produced overseas) have flooded the Canadian market for decades, despite the best efforts of Hunt and other advocates. Currently, Senator Patricia Bovey—the first art historian in the Senate—is lobbying the government to fortify copyright law to protect intellectual property and provide more protections for First Nations artists. She says there may be millions lost to art fakes and wants the government to do more to help artists track down those unlawfully reproducing their works by conducting a thorough review of the Copyright Act in order to ensure there are proper legal protections in place. In the meantime, Hunt says Canada’s art market remains a free-for-all for unscrupulous fraudsters. This is his story.

— As told to Liza Agrba

I’ve been a professional carver for 30 years. I come from a long line of Kwaguilth carvers, including my uncle Richard and my dad, Stan. Our family is full of artists, and I’m lucky enough to be one of them. But, like many First Nations artists, I spend my off-time trying to rein in the enormous market for fraudulent artwork, and have been doing so since I began my career.

Every element of North West Coast art is being stolen and reproduced. It runs the gamut from inspired designs thrown on cheap mugs and T-shirts to detailed reproductions passed off as the real thing and sold at a high price. Outright copyright theft is extremely common. In Canada, artists have implicit rights to a piece as soon as it’s created—that is, you don’t have to go out and copyright every individual work of art. But in practice, pieces are stolen all the time, with virtually no repercussions.

If you visit cities like Vancouver, Banff or any of these touristy places, you’ll find more fraudulent First Nations artwork than authentic pieces. When I was in Jasper a couple of years ago, every gallery I walked into—including some of the nicer ones—were filled with reproduction garbage promoted as real. It’s disheartening.

There are few to no consequences for people who do this. Ten or so years ago, one of the largest slot machine manufacturers in the world stole the design for one of my masks and put it onto their machines. The only reason I found out is because my wife was playing the machine at a casino in Vancouver. I sat down beside her and noticed. What the heck!? That’s my mask on the screen! I talked to one of their lawyers at the time, who agreed it looks like the same piece of artwork, but said that if it ever goes to court I’d have to do a lot more to prove it’s my piece. They are a massive company, and I couldn’t afford a lawyer to go after it.

There are countless examples of this. There was even one guy who hired a crew to create artwork and went as far as creating a fake artist persona. He sold to galleries for 10 or 15 years until a few of us artists started looking into him a little more because the work just didn’t look right. As with many of these fraudulent pieces, much of the work looks completely ridiculous to an actual carver. But to the average Joe, it looks legitimate. Someone he knew ended up ratting him out, and thankfully, you don’t see his pieces anymore. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

There are red flags to look for. One extremely common pattern is online posts with some version of this elaborate fairytale backstory: “I collected this piece at an estate sale; it’s been sitting in an attic for decades. It’s a long-lost masterpiece!” When I read that I think: buyer beware. It also helps to do some research on the artist—there should be something to corroborate who this person is. Also, when it comes to wood carvings you can look out for the type of wood being used. Generally, the real thing is made with red or yellow cedar. Another big tell is artwork that doesn’t have a signature. Every artist signs their work—don’t believe sellers who say the signature rubbed off.

Online selling has made this industry all the more prolific. In my earlier days I was battling eBay. I would sit around emailing buyers and sellers to warn them off. Now, sites like Redbubble, which sell work from ostensibly independent artists, will occasionally get on board to take fraudulent work down when it’s pointed out to them. But in my experience they’re absolutely uninterested in being proactive about it.

Even though we supposedly have laws in Canada to protect us, there’s no active enforcement. Because there’s no large-scale effort to tackle the issue it’s up to individual artists to do their best with whatever resources we may have. Believe me, it’s expensive to prove that a given piece is yours.

Enough is enough. We need a united approach, so we’re not all fighting this fight in little siloes. Maybe we need to fund a committee to tackle this problem, or stronger checks at the border for pieces that look like First Nations artwork. In the United States they have more severe penalties for people who reproduce First Nations artwork and pass it off as real. We need stronger policies and copyright protections.

There are a lot of artists passionate about this—we have Facebook groups and other forums dedicated to the effort. The Vancouver-based artist Lucinda Turner, who recently passed away, really spearheaded this effort. She would send thousands of cease-and-desist letters to online resellers. Since she’s passed, it’s even more of a free-for-all than before. We can’t keep up. It’s like playing whack-a-mole.

It’s emotionally draining. I’ve been battling this for 30 years, and it’s just getting worse. I’m lucky because I have a name in the art world, so I’m not necessarily losing out on the ability to market my work. But it really affects younger artists. Frankly, I think that’s part of the reason there are so few of them. I’ll be 50 in a couple of years, and I’m the youngest person in my family making a living with my art.

If you look at this with a broader lens, the uniqueness of our art is being watered down. There’s a very specific method to what we do. The designs are not just put together randomly. It takes generational knowledge to know how to do this. I was taught by my dad, who was taught by my grandpa, who was taught by his great-grandpa, and so on. That’s what gives the art meaning.

But when you have these generic reproductions, there’s no culture behind it. I wonder if there may be more fraudulent pieces on the market than there are genuine ones. Are we getting washed out? Maybe. It’s heartbreaking because there’s a huge market for this art, but we’re stuck battling theft on a massive scale. At this point we need government support and protections, and we need it now.

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

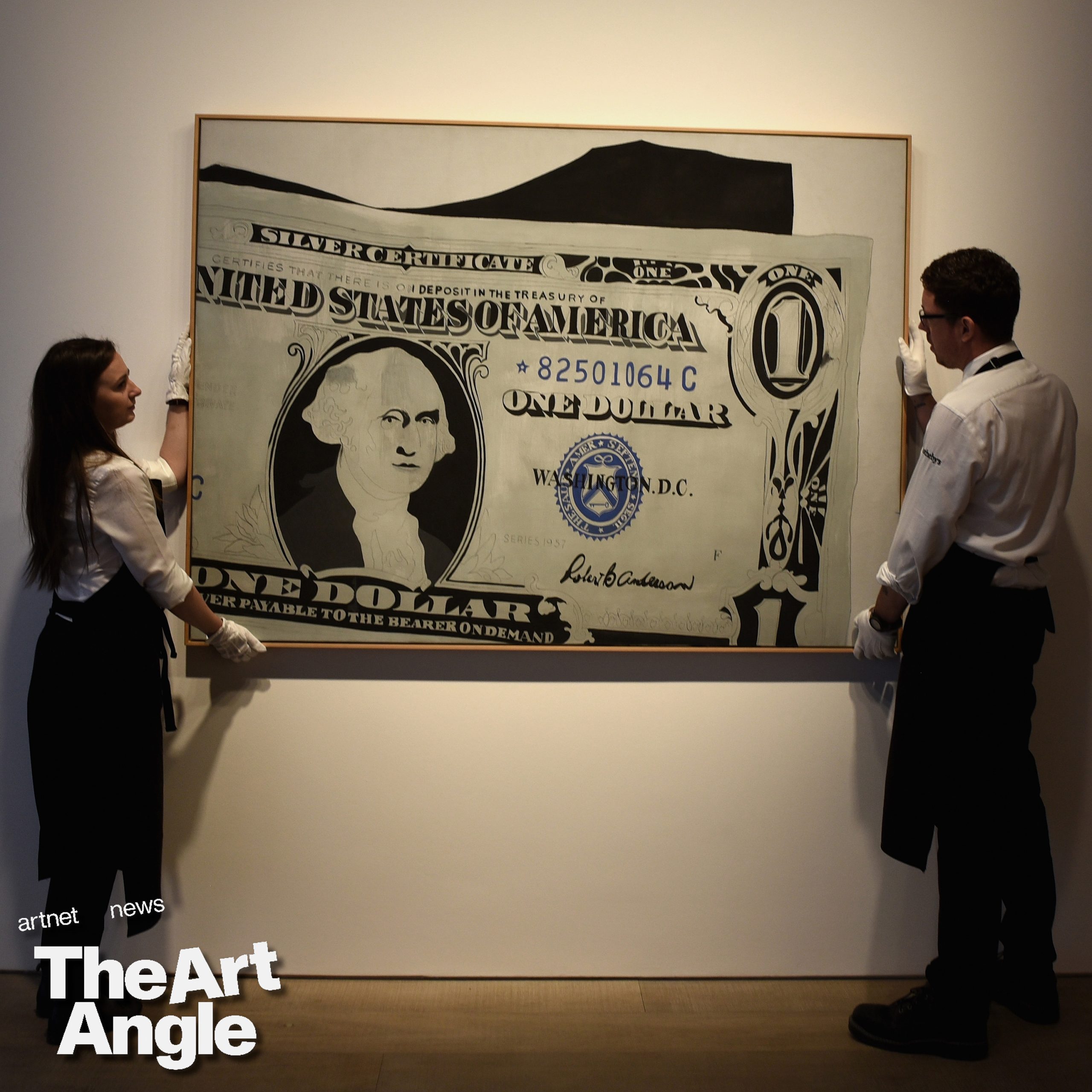

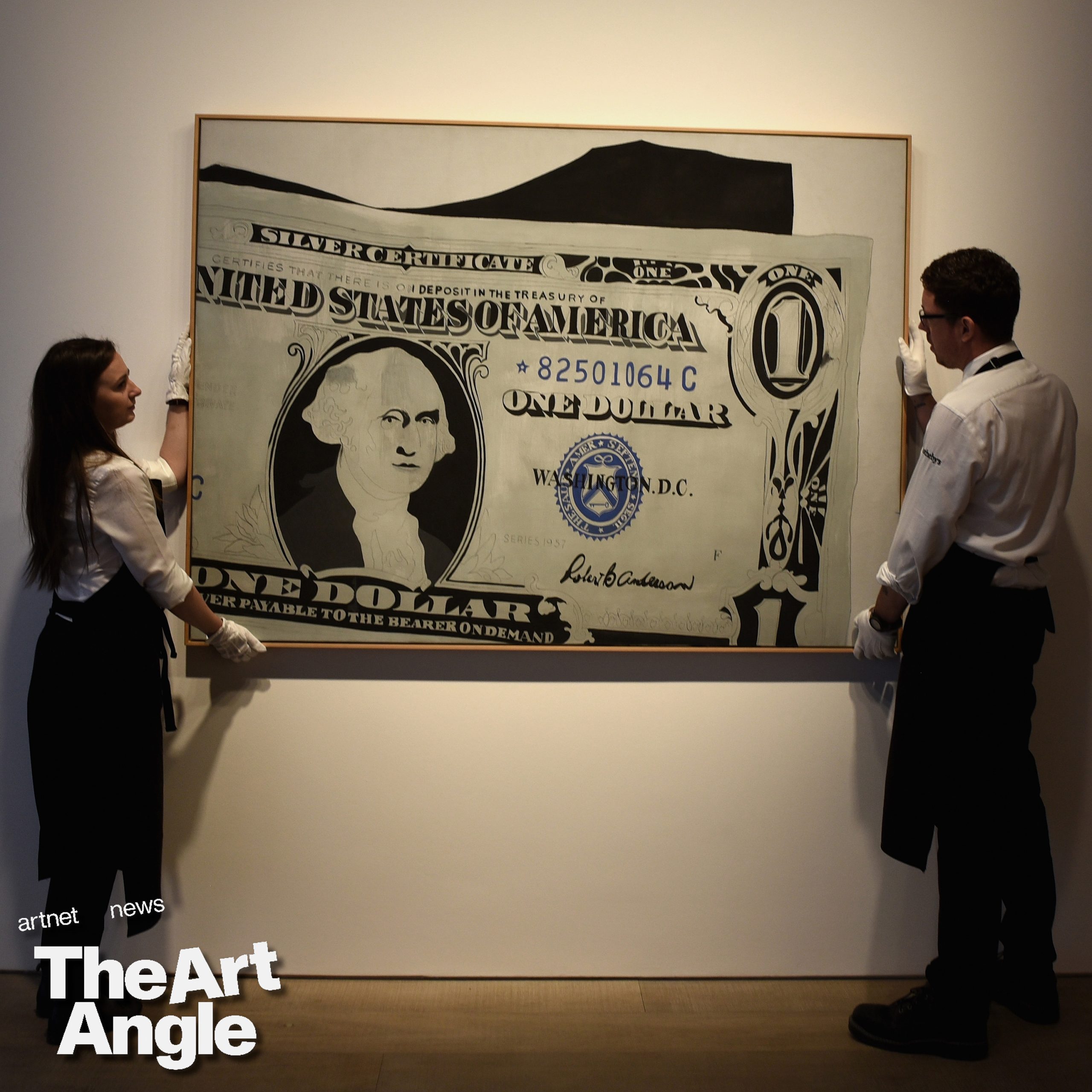

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Digital artist Sam Spratt is living the artist’s dream. This week, he celebrated the opening of “The Monument Game,” his first-ever art show. But it wasn’t a group show in some DIY space in New York, where he is based, like so many artists typically start out, but a solo exhibition in Venice, during the art world’s biggest event of the year—the Venice Biennale. How did Spratt–a virtually unknown name in the art world–make such a tremendous leap? With a little help from his friends, of course, including Ryan Zurrer, the venture capitalist turned digital art champion.

“Something the capital ‘A’ art world doesn’t recognize is the power of the collective, it sometimes leans into the cult of the individual,” Ryan Zurrer told ARTnews during a preview of the opening. “But this show is supported by the entire community around Sam.”

Spratt’s Venice exhibition was put on by 1OF1 Collection, a “collecting club” set up by Zurrer to nurture digital artists working in the NFT space. Since its launch in 2021, 1OF1 has been uniquely successful in bridging the gap between the art world and the Web3 community. Last year, 1OF1 and the RFC Art Collection gifted Anadol’s Unsupervised – Machine Hallucinations – MoMA to the museum, after nearly a year on view in the Gund Lobby. Zurrer also arranged the first museum presentations of Beeple’s HUMAN ONE, a seven-foot-tall kinetic sculpture based on video works, showing it first at Castello di Rivoli in Italy and the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, before sending it to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

With “The Monument Game,” Zurrer is once again placing digitally native art at the center of the art world. While Anadol and Beeple had large cultural footprints prior to Zurrer’s patronage, Spratt is far earlier in his career. But, what attracted Zurrer, he said, was the artist’s shrewd approach to building a dedicated, participatory audience for his work. He did so by making his art a game.

“When I first started looking at NFTs, I spent a long time just figuring out who the players were,” Spratt told ARTnews. “The auctions were like stories in themselves, I could see people’s friends bidding, almost ceremonially, to give the auction some energy, and then other people would come in, and it would get competitive, emotional.”

Spratt released his first three NFTs on the platform SuperRare in October 2021. The sale of those works, the first from his series LUCI, was accompanied by a giveaway of a free NFT to every person who put in a bid. Zurrer had been one of those underbidders (for the work Birth of Luci). While Spratt said the derivative NFTs were basically worthless, he wanted to give something back to each bidder. Zurrer, and others it seems, appreciated the gesture and Spratt quickly gained a following in the Web3 space. The offerings he gave, called Skulls of Luci, became Sam’s dedicated collectors that now go by The Council of Luci. 47 editions were given out and Spratt held back three.

All the works from LUCI are on view at the Docks Cantiere Cucchini, a short walk from the Arsenale, past a rocking boat that doubles as a fruit and vegetable market and over a wooden bridge. Though NFTs typically bring to mind glitching screens and monkey cartoons (ala Bored Ape Yacht Club), the ten works on view depict apes in a detailed, painterly style and emit a soft glow. Taking cues from photography installations, 1OF1 ditched screens in favor of prints mounted on lightboxes.

“We don’t want it to look like a Best Buy in here,” said Zurrer.

Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

Each work represents a chapter in a fantasy world that Spratt dreamed up. Though there’s no book of lore to refer to, there seems to be some Planet of the Apes story at play in which an intelligent ape lives alongside humans, babies, and ape-human hybrids. Spratt received an education in oil painting at Savannah College of Art and Design and he credits that technical training with his ability to bring warmth and detail to the digital works. He and the team often say that his art historical references harken to Renaissance and Baroque art, though the aesthetics—to my eye—seem to pull from commercial illustration and concept art. That isn’t too surprising given that this was the environment that Spratt started off in after graduating SCAD in 2010.

“After school I was confronted with the reality that for a digital artist the only path was commercial,” Spratt said.

He did quite well on that path, producing album covers for Childish Gambino, Janelle Monae, and Kid Cudi and bagging clients like Marvel, StreetEasy, and Netflix. Spratt also enjoys a huge audience of fans who have followed him as he’s migrated from Facebook to Tumblr to Twitter and Instagram, posting his hyper-realistic fan-art on each platform. Despite the apparent success, Spratt spoke of the work with bitterness.

“I was a gun for hire. A mimic, hired to be 30% me and 70% someone else,” he said.

Spratt’s personal life blew up when he turned 30 and he traced some of the mistakes he made in his relationships with the fact that he had spent so much of his career “telling other people’s stories.” NFTs seemed like a way out of commercial illustration and a way into an original art practice.

For his latest piece in the LUCI series, Spratt digitally painted a massive landscape set in this ape-human world titled The Monument Game. For the piece, Spratt initially sold NFTs that would turn 209 collectors into “players” (since another edition of 256 NFTs was given to the Council to “curate” new champions”). Each player would then be allowed to make an observation about the painting. The Council of Luci would vote on which three observations were best, and those three Players would receive one of the Skulls of Luci NFTs that Spratt held back. By creating these tiers of engagement, with his Council and player structure, Spratt pushes digital collectors to give the kind of care to his work that more traditional collectors do.

A work at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

“Jeff Koons said that the average person looks at a work of art for twenty seconds,” Lukas Amacher, 1OF1’s Artistic Director and the curator of the show, told ARTnews. “Sam has found a way to get people to engage in his work for much longer.”

The game Spratt has designed for the Venice exhibition might seem too gamified to fit the art world’s notion of art, but as Amacher and Zurrer suggest, in the Web3 environment, value is built by finding alternative ways to create investment and attention in what are typically immaterial digital artifacts. And it’s working. Thus far, the LUCI series has generated $2 million in primary sales and about $4 million in additional secondary volume. The challenge now, as it has been for the past three years, is to see if art’s gatekeepers will take this work seriously.

At the presentation of The Monument Game in Venice, an observation deck, built by platform Nifty Gateway, sits in front of the mounted work. Participants can click on the painting on the screen and write down their observations of the work in front of them, no NFT required. The first observation came from star curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli and curator of Documenta 15: a tribute to art dealer Marian Goodman. The second was from Zurrer. Who’s next?

“Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” is on view until June 21 at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

Type 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

Tofino, Pemberton among communities opting in to B.C.'s new short-term rental restrictions – Vancouver Sun

A sunken boat dream has left a bad taste in this Tim Hortons customer's mouth – CBC.ca

Start time set for Game 1 in Maple Leafs-Bruins playoff series – Toronto Sun