Art

LEDs Change Everything

Just before Christmas, I took my kids to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden for an exhibition called “Lightscape.” Neon lights electrified trees and made the gardens glow. In one large field, hundreds of illuminated orbs pulsed, making it seem as if a gentle tide were flowing in and out; arbors became like candlelit cathedrals.

“Lightscape” is one of many such exhibitions in New York of late. There’s the wonderful “Invisible Worlds” interactive at the Natural History Museum, installations featuring the art of Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky at the Hall des Lumières, a garden night walk called “Astra Lumina” in Queens, even a multisensory experience at the, cough, House of Cannabis. The phenomenon is not limited to major cities with big museums, either. I went to a pretty cool light show in Naples, Florida.

A lot has been written about immersive spaces as flourishing commercial and cultural products, sometimes transformative and sometimes cheesy ones. The experiential-art boom is a result of artists and museums appealing to younger audiences, different audiences, tech money. It comes from designers satisfying the Millennial demand for experiences. It is driven by the profitability of Instagram tableaux: monochromatic ball pits, ice-cream sundaes on fire, perfect wee pubs, and, yes, rooms filled with glowing lights. The rise of legal weed and the increasing normalization of psychedelics seem like they might be factors too. But there’s a simpler, more straightforward explanation that somehow, despite its blaring glare, has gone overlooked. That is the radical improvement in and plummeting cost of LEDs.

Virtually nothing has gotten better and cheaper faster over the past 30 years than LEDs. From 2010 to 2019 alone, LEDs went from accounting for 1 percent of the global lighting market to nearly 50 percent, while their cost has declined “exponentially,” as much as 44 percent a year, one government report found. And as LEDs have improved, so, too, have any number of technologies reliant on or related to them: tablets, at-home-hair-removal devices, televisions, smartphones, light-up toys, cameras.

LEDs have also transformed cultural events involving creative lighting. They’re why stadium shows and EDM festivals look so freaking awesome, to fangirl for a minute, and why even many just-getting-started bands have pretty neat light displays. They’re why so many parks and zoos are lit up like Burning Man at night. They’re an integral element of today’s underground-dance-party revival, and why our cities are all of a sudden studded with rave caves.

LED technology is an old one: Scientists invented light-emitting diodes in the early 20th century. But “the big-bang moment” came only in the 1990s, Morgan Pattison, an engineer and materials scientist, explained to me. Three physicists—Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano of Japan and Shuji Nakamura of the United States and Japan—invented blue LEDs. With that scientific advance, manufacturers were able to create LEDs emitting white light and the full rainbow of visible colors, something they had not been able to do before. (The three scientists shared a 2014 Nobel Prize for their discovery.)

LED lights have many advantages. For one, they are hyperefficient. Incandescent bulbs contain a filament that radiates when it gets hot; most of the energy they draw gets wasted as heat rather than used as light. (In a standard 75-watt bulb, the filament might heat up to 4,500 degrees.) LEDs, in contrast, consist of semiconductor materials that emit light when energy passes through them; they generate little heat and waste little energy, using one-tenth the energy of incandescents or less. LEDs last several times longer too, because there are no filaments to burn out. As a result, they’re more expensive up front but cheaper in the long term.

LED lights are also much more flexible than their incandescent predecessors. You can command a single LED bulb to get dimmer or brighter with no need for a dimmer switch; you can tell it to glow pink or orange or to cycle through a sunset of colors. “The manufacturers have just nailed that super fast,” Pattison told me. “We have all these tunable lights. The bigger issue is, at the end of the day, what do people do with them?” At home, he told me, he barely dims his lights: “I don’t go around changing the colors all the time.” But artists and lighting designers do. And LEDs have revolutionized their work.

The programmability of these lights is the main characteristic that distinguishes them from incandescents before them: You could point a spotlight around and put filters on top of it, but you couldn’t do anything like what LEDs do, at least not easily. Anthony Rowe and Liam Birtles are members of the British collective Squidsoup, whose 2013 work Submergence is one of the most famous (and most copied) immersive digital artworks. The idea, Rowe told me, was to “explode” a screen, allowing a viewer to float among its pixels. In their new collaboration with the electronic musician Four Tet, hundreds of people dance while heaven-lit by thousands of suspended LED lights that somehow seem to be both a synesthetic representation of the music and capable of bouncing along with the crowd.

LEDs can also be programmed to respond to the people viewing them. At the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, for instance, suspended lights darkened and brightened as you walked under them. J. T. Rooney of Silent Partners Studio, which has designed for Taylor Swift, Harry Styles, and Doja Cat, told me about creating touch-sensitive LED floors that generate trails of fire or water behind people as they walk, and responsive LED screens that mirror a person’s movements back at them.

It’s not just the LEDs, many designers and artists told me. Lasers and projectors have gotten a lot better and cheaper. The software has improved dramatically, so much so that a person with a laptop can do in an afternoon what a motion-picture studio might have taken years to do two decades ago. “Emerging technologies—whether it be LED walls or panels, microcontroller development boards, components like sensors and cameras” are constantly progressing, Kevin Colorado of Artechouse, which runs immersive spaces in New York, Miami, and D.C., told me. “We get to build our own dreams in hardware, and breathe life into them” with software.

That has led to the creation of new spaces such as Artechouse’s. Last month, I went to its installation in the basement of Chelsea Market. A dozen or so people sat in a cavernous room, enveloped by a set of hyperreal, color-saturated videos—endless tubes, glowing trains, galaxies floating within orbs, sacred geometry—while listening to ambient music. It was a bit like being inside a Thomas Kinkade painting, I thought, if Kinkade really liked magic mushrooms.

If you don’t want to leave the warm glow of your ordinary LEDs at home, you can still see how far we’ve come by checking out this video of Madonna performing “Like a Prayer” on her Re-Invention World Tour, in 2004. Then check her out performing the same song on the Celebration Tour last year. Ignore, if you can, the shirtless go-go dancers wearing gimp masks, and focus on the lights: The rigged screens are huge! The lighting pattern is so complicated! Everything is so bright! Or, if you prefer, check out Beyoncé dazzling a decade ago, then take a look at what she brought on tour last summer. She goes from commanding a stage to commanding a moonbase.

Indeed, everywhere feels like it is lit like a moonbase these days. The orbs and lanterns in my kids’ bedroom make it look like Shibuya Crossing on Halloween. You might walk through a neon-lit immersive space in a mall or an airport, scarcely noticing it but for the bright lights. You might pay $54.99 to imagine yourself part of a Van Gogh painting—whether the artist wanted you to be part of his painting or not—while zonked out on an edible on a Tinder date.

The LEDs of the future may be able to do much more, Pattison told me, from powering vertical farms to improving surgical outcomes. “It’s the same level of technology jump as going from gas lights to incandescent,” he said. Artists need time to catch up too, Birtles told me: “Art leads technology, and technology leads art … The light-art world is slightly struggling to keep up with the technology and come up with ideas that really work.” He likened it to the advent of film: “The first cameras emerged, and people went and filmed things like trains coming out of a station. Gradually, this filmic language developed.” What new languages will we create with light?

Art

Calvin Lucyshyn: Vancouver Island Art Dealer Faces Fraud Charges After Police Seize Millions in Artwork

In a case that has sent shockwaves through the Vancouver Island art community, a local art dealer has been charged with one count of fraud over $5,000. Calvin Lucyshyn, the former operator of the now-closed Winchester Galleries in Oak Bay, faces the charge after police seized hundreds of artworks, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, from various storage sites in the Greater Victoria area.

Alleged Fraud Scheme

Police allege that Lucyshyn had been taking valuable art from members of the public under the guise of appraising or consigning the pieces for sale, only to cut off all communication with the owners. This investigation began in April 2022, when police received a complaint from an individual who had provided four paintings to Lucyshyn, including three works by renowned British Columbia artist Emily Carr, and had not received any updates on their sale.

Further investigation by the Saanich Police Department revealed that this was not an isolated incident. Detectives found other alleged victims who had similar experiences with Winchester Galleries, leading police to execute search warrants at three separate storage locations across Greater Victoria.

Massive Seizure of Artworks

In what has become one of the largest art fraud investigations in recent Canadian history, authorities seized approximately 1,100 pieces of art, including more than 600 pieces from a storage site in Saanich, over 300 in Langford, and more than 100 in Oak Bay. Some of the more valuable pieces, according to police, were estimated to be worth $85,000 each.

Lucyshyn was arrested on April 21, 2022, but was later released from custody. In May 2024, a fraud charge was formally laid against him.

Artwork Returned, but Some Remain Unclaimed

In a statement released on Monday, the Saanich Police Department confirmed that 1,050 of the seized artworks have been returned to their rightful owners. However, several pieces remain unclaimed, and police continue their efforts to track down the owners of these works.

Court Proceedings Ongoing

The criminal charge against Lucyshyn has not yet been tested in court, and he has publicly stated his intention to defend himself against any pending allegations. His next court appearance is scheduled for September 10, 2024.

Impact on the Local Art Community

The news of Lucyshyn’s alleged fraud has deeply affected Vancouver Island’s art community, particularly collectors, galleries, and artists who may have been impacted by the gallery’s operations. With high-value pieces from artists like Emily Carr involved, the case underscores the vulnerabilities that can exist in art transactions.

For many art collectors, the investigation has raised concerns about the potential for fraud in the art world, particularly when it comes to dealing with private galleries and dealers. The seizure of such a vast collection of artworks has also led to questions about the management and oversight of valuable art pieces, as well as the importance of transparency and trust in the industry.

As the case continues to unfold in court, it will likely serve as a cautionary tale for collectors and galleries alike, highlighting the need for due diligence in the sale and appraisal of high-value artworks.

While much of the seized artwork has been returned, the full scale of the alleged fraud is still being unraveled. Lucyshyn’s upcoming court appearances will be closely watched, not only by the legal community but also by the wider art world, as it navigates the fallout from one of Canada’s most significant art fraud cases in recent memory.

Art collectors and individuals who believe they may have been affected by this case are encouraged to contact the Saanich Police Department to inquire about any unclaimed pieces. Additionally, the case serves as a reminder for anyone involved in high-value art transactions to work with reputable dealers and to keep thorough documentation of all transactions.

As with any investment, whether in art or other ventures, it is crucial to be cautious and informed. Art fraud can devastate personal collections and finances, but by taking steps to verify authenticity, provenance, and the reputation of dealers, collectors can help safeguard their valuable pieces.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

-

Sports12 hours ago

Sports12 hours agoArmstrong scores, surging Vancouver Whitecaps beat slumping San Jose Earthquakes 2-0

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoAs plant-based milk becomes more popular, brands look for new ways to compete

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoLooking for the next mystery bestseller? This crime bookstore can solve the case

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoLabour Minister praises Air Canada, pilots union for avoiding disruptive strike

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoCF Montreal finds its groove with 2-1 win over Charlotte

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoToronto FC downs Austin FC to pick up three much-needed points in MLS playoff push

-

News12 hours ago

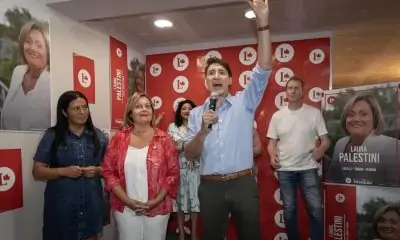

News12 hours agoLiberal candidate in Montreal byelection says campaign is about her — not Trudeau

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoInflation expected to ease to 2.1%, lowest level since March 2021: economists