Science

Meet My Friend, the Heartbreak Heron

On the top of the apartment building kitty-corner to mine, a single blue heron sits on the roof. Almost every day, it’s there: wind, rain, snow or subarctic temperatures, the heron sits alone. Sometimes the bird is so still that I think it’s frozen in place. Other times, the wind ruffles its long feathers, sending them rippling out like long silver streamers.

While watching this creature, it occurred to me, do animals get bored? What exactly is that heron thinking about? Is it ruminating on past wrongs, planning a diabolical revenge, or simply thinking, “Where can I get some good takeout on this here roof?” I’m not sure why the heron talks like a southern gentleman, but the shadow of Foghorn Leghorn lingers long inside my head in all things bird related.

Animals are not humans, of course, so it’s impossible to know what goes on in this bird’s brain. It certainly looks like it is thinking hard, hunched over like an ancient reminder of dinosaurs past. Herons are raptors, after all. Birds of prey. Maybe this is what occupies its days: genetic memories of a glorious rampaging, a time long before humans and their all-consuming ways had taken over most of the planet.

The question of animal sentience is an interesting one, and once you start to think about it, more questions arise. How might bird thoughts differ from those of racoons or skunks? With octopus intelligence well established, how do we justify eating the poor suckers? But truly this is the case for almost all creatures, big or small. These days, I feel bad if I kill a silverfish. What if his silverfish mother is waiting for him to squiggle home and he never does? The guilt that comes just from existing in this world!

But back to our buddy the heron.

Illustration for The Tyee by Dorothy Woodend.

When it is sitting atop the roof, staring bleakly down at the human world, what does it see? Tourists headed out to zip gaily around the park on rented bikes. Locals staggering home with groceries and bottles of wine. From this vantage point, the heron sees all.

The other birds in the neighbourhood are equally busy, the crows staging ongoing wars with the seagulls, the riot of starlings making an unholy racket, and the flying jewel of a hummingbird, sitting still for an instant on the bare branches of a cherry tree, before zipping off on a critical errand, like a bullet of emerald green and ruby red.

To the human eye, at least, each animal is distinct in its personality, needs and wants. The crows are gregarious and social; the seagulls are the bully boys of the bird world. My neighbour is convinced that one particularly thuggish gull is trying to break into her apartment. Maybe she’s right? And deep in the night, the call of an owl: you can hear them, but you rarely see them. I still recall one sighting that was only a shadowy fleeting presence so riveting that all the hair on the back of my neck stood up like a mini hirsute army.

The heron rookery in Stanley Park is only a couple of blocks away and has been going so strong, for many years, that it is mentioned on the Wikipedia page dedicated to the habits and lifestyle of great blue herons.

The Stanley Park rookery is such a beloved local West End fixture that it features a heron cam, an adopt-a-nest initiative ($54!) and a documentary film. Coolio! At least to me. Other folks are less than thrilled with the raucous noise and interesting smells emanating from heron central.

Illustration for The Tyee by Dorothy Woodend.

When you look closely at herons, they are startling in the design elements, like something dreamed up by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The famed Scottish artist, who was a prominent member of the Glasgow School art and design movement, couldn’t have dreamed up a more elegant palette: slate blue, silver grey, with a delicate stippled border of darker feathers, handsome in extremis. Who could not love this lovely fella?

It’s an ongoing human habit to transfer emotions, needs and wants onto some poor unsuspecting animal. We’ve been doing it since we clambered out of the trees, picked up a bit of charcoal and started drawing pictures of beasts, both big and small, on cave walls. According to researchers, the oldest known depiction of an animal is an Indonesian cave painting of a pig, of all creatures.

Herons aren’t immune to this anthropomorphic habit. They’re probably even more prone to it, sitting as still as they do, so that we people can gaze long and hard upon them.

Illustration for The Tyee by Dorothy Woodend.

The other day, I looked out the window and the heron was gone. No forwarding address, no friendly wave to say so long. It just vanished. But in his absence, I’ve decided he is a he — a female bird probably has other priorities and a greater social circle as well. She’s probably cackling with the other female herons, about how silly the males in this town are. Maybe that’s what he’s doing up there, thinking about love gone wrong. The loneliness seems palpable. So maybe it’s not boredom, but heartbreak.

The Heartbreak Heron, as I now think of him, has come to symbolize all the lone creatures, taking a stand out there in the wide, wild world.

Maybe when the springtime season of romance rolls back around, the lone bird will take to the skies and find love once more. There’s hope for all us creatures. At least, I hope so. ![]()

Science

Asteroid Apophis will visit Earth in 2029, and this European satellite will be along for the ride

The European Space Agency is fast-tracking a new mission called Ramses, which will fly to near-Earth asteroid 99942 Apophis and join the space rock in 2029 when it comes very close to our planet — closer even than the region where geosynchronous satellites sit.

Ramses is short for Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety and, as its name suggests, is the next phase in humanity’s efforts to learn more about near-Earth asteroids (NEOs) and how we might deflect them should one ever be discovered on a collision course with planet Earth.

In order to launch in time to rendezvous with Apophis in February 2029, scientists at the European Space Agency have been given permission to start planning Ramses even before the multinational space agency officially adopts the mission. The sanctioning and appropriation of funding for the Ramses mission will hopefully take place at ESA’s Ministerial Council meeting (involving representatives from each of ESA’s member states) in November of 2025. To arrive at Apophis in February 2029, launch would have to take place in April 2028, the agency says.

This is a big deal because large asteroids don’t come this close to Earth very often. It is thus scientifically precious that, on April 13, 2029, Apophis will pass within 19,794 miles (31,860 kilometers) of Earth. For comparison, geosynchronous orbit is 22,236 miles (35,786 km) above Earth’s surface. Such close fly-bys by asteroids hundreds of meters across (Apophis is about 1,230 feet, or 375 meters, across) only occur on average once every 5,000 to 10,000 years. Miss this one, and we’ve got a long time to wait for the next.

When Apophis was discovered in 2004, it was for a short time the most dangerous asteroid known, being classified as having the potential to impact with Earth possibly in 2029, 2036, or 2068. Should an asteroid of its size strike Earth, it could gouge out a crater several kilometers across and devastate a country with shock waves, flash heating and earth tremors. If it crashed down in the ocean, it could send a towering tsunami to devastate coastlines in multiple countries.

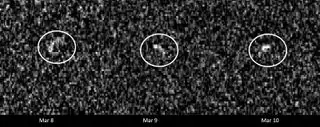

Over time, as our knowledge of Apophis’ orbit became more refined, however, the risk of impact greatly went down. Radar observations of the asteroid in March of 2021 reduced the uncertainty in Apophis’ orbit from hundreds of kilometers to just a few kilometers, finally removing any lingering worries about an impact — at least for the next 100 years. (Beyond 100 years, asteroid orbits can become too unpredictable to plot with any accuracy, but there’s currently no suggestion that an impact will occur after 100 years.) So, Earth is expected to be perfectly safe in 2029 when Apophis comes through. Still, scientists want to see how Apophis responds by coming so close to Earth and entering our planet’s gravitational field.

“There is still so much we have yet to learn about asteroids but, until now, we have had to travel deep into the solar system to study them and perform experiments ourselves to interact with their surface,” said Patrick Michel, who is the Director of Research at CNRS at Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice, France, in a statement. “Nature is bringing one to us and conducting the experiment itself. All we need to do is watch as Apophis is stretched and squeezed by strong tidal forces that may trigger landslides and other disturbances and reveal new material from beneath the surface.”

By arriving at Apophis before the asteroid’s close encounter with Earth, and sticking with it throughout the flyby and beyond, Ramses will be in prime position to conduct before-and-after surveys to see how Apophis reacts to Earth. By looking for disturbances Earth’s gravitational tidal forces trigger on the asteroid’s surface, Ramses will be able to learn about Apophis’ internal structure, density, porosity and composition, all of which are characteristics that we would need to first understand before considering how best to deflect a similar asteroid were one ever found to be on a collision course with our world.

Besides assisting in protecting Earth, learning about Apophis will give scientists further insights into how similar asteroids formed in the early solar system, and, in the process, how planets (including Earth) formed out of the same material.

One way we already know Earth will affect Apophis is by changing its orbit. Currently, Apophis is categorized as an Aten-type asteroid, which is what we call the class of near-Earth objects that have a shorter orbit around the sun than Earth does. Apophis currently gets as far as 0.92 astronomical units (137.6 million km, or 85.5 million miles) from the sun. However, our planet will give Apophis a gravitational nudge that will enlarge its orbit to 1.1 astronomical units (164.6 million km, or 102 million miles), such that its orbital period becomes longer than Earth’s.

It will then be classed as an Apollo-type asteroid.

Ramses won’t be alone in tracking Apophis. NASA has repurposed their OSIRIS-REx mission, which returned a sample from another near-Earth asteroid, 101955 Bennu, in 2023. However, the spacecraft, renamed OSIRIS-APEX (Apophis Explorer), won’t arrive at the asteroid until April 23, 2029, ten days after the close encounter with Earth. OSIRIS-APEX will initially perform a flyby of Apophis at a distance of about 2,500 miles (4,000 km) from the object, then return in June that year to settle into orbit around Apophis for an 18-month mission.

Related Stories:

Furthermore, the European Space Agency still plans on launching its Hera spacecraft in October 2024 to follow-up on the DART mission to the double asteroid Didymos and Dimorphos. DART impacted the latter in a test of kinetic impactor capabilities for potentially changing a hazardous asteroid’s orbit around our planet. Hera will survey the binary asteroid system and observe the crater made by DART’s sacrifice to gain a better understanding of Dimorphos’ structure and composition post-impact, so that we can place the results in context.

The more near-Earth asteroids like Dimorphos and Apophis that we study, the greater that context becomes. Perhaps, one day, the understanding that we have gained from these missions will indeed save our planet.

Science

McMaster Astronomy grad student takes a star turn in Killarney Provincial Park

Astronomy PhD candidate Veronika Dornan served as the astronomer in residence at Killarney Provincial Park. She’ll be back again in October when the nights are longer (and bug free). Dornan has delivered dozens of talks and shows at the W.J. McCallion Planetarium and in the community. (Photos by Veronika Dornan)

BY Jay Robb, Faculty of Science

July 16, 2024

Veronika Dornan followed up the April 8 total solar eclipse with another awe-inspiring celestial moment.

This time, the astronomy PhD candidate wasn’t cheering alongside thousands of people at McMaster — she was alone with a telescope in the heart of Killarney Provincial Park just before midnight.

Dornan had the park’s telescope pointed at one of the hundreds of globular star clusters that make up the Milky Way. She was seeing light from thousands of stars that had travelled more than 10,000 years to reach the Earth.

This time there was no cheering: All she could say was a quiet “wow”.

Dornan drove five hours north to spend a week at Killarney Park as the astronomer in residence. part of an outreach program run by the park in collaboration with the Allan I. Carswell Observatory at York University.

Dornan applied because the program combines her two favourite things — astronomy and the great outdoors. While she’s a lifelong camper, hiker and canoeist, it was her first trip to Killarney.

Bruce Waters, who’s taught astronomy to the public since 1981 and co-founded Stars over Killarney, warned Dornan that once she went to the park, she wouldn’t want to go anywhere else.

The park lived up to the hype. Everywhere she looked was like a painting, something “a certain Group of Seven had already thought many times over.”

She spent her days hiking the Granite Ridge, Crack and Chikanishing trails and kayaking on George Lake. At night, she went stargazing with campers — or at least tried to. The weather didn’t cooperate most evenings — instead of looking through the park’s two domed telescopes, Dornan improvised and gave talks in the amphitheatre beneath cloudy skies.

Dornan has delivered dozens of talks over the years in McMaster’s W.J. McCallion Planetarium and out in the community, but “it’s a bit more complicated when you’re talking about the stars while at the same time fighting for your life against swarms of bugs.”

When the campers called it a night and the clouds parted, Dornan spent hours observing the stars. “I seriously messed up my sleep schedule.”

She also gave astrophotography a try during her residency, capturing images of the Ring Nebula and the Great Hercules Cluster.

“People assume astronomers take their own photos. I needed quite a lot of guidance for how to take the images. It took a while to fiddle with the image properties, but I got my images.”

Dornan’s been invited back for another week-long residency in bug-free October, when longer nights offer more opportunities to explore and photograph the final frontier.

She’s aiming to defend her PhD thesis early next summer, then build a career that continues to combine research and outreach.

“Research leads to new discoveries which gives you exciting things to talk about. And if you’re not connecting with the public then what’s the point of doing research?”

Science

Where in Vancouver to see the ‘best meteor shower of the year’

Eyes to the skies, Vancouver, because between now and September 1st, stargazers can witness the ‘best meteor shower of the year’ according to NASA.

Known for its “long wakes of light and colour,” the Perseid Meteor Shower will peak on August 12th, 2024 – so consider this list a great place to start if you’re in search of a prime stargazing spots!

Grab your lawn chairs and blankets, and seek as little light pollution as possible. Here are some ideal stargazing spots to check out in and around Vancouver this summer.

Recent Posts:

This island with clear waters has one of the prettiest towns in BC

10 beautiful lake towns to visit in BC this summer

Wreck Beach

If you’re willing to brave the stairs and the regulars, it doesn’t get much better than Wreck Beach for watching the skies – for both sunsets and stargazing. The west-facing views practically eliminate immediate distractions from the city lights.

Spanish Banks Park

Spanish Banks is the perfect mixture of convenience and quality. Its location offers unobstructed views of the skies above, and it’s far enough away from downtown to mitigate some of the light pollution.

Burnaby Mountain Park

If it’s good enough for a university observatory, it’s good enough for us. Pretty much anywhere on Burnaby Mountain will offer tremendous viewpoints, but the higher you get the better (safely).

Porteau Cove

A short drive from Vancouver gets you incredible views of the Howe Sound from directly on the water. And naturally, its distance from any nearby community makes it a prime spot for stargazing.

Cypress Mountain

In addition to having one of the best viewpoints in Vancouver period, Cypress Mountain (and the road up to it) is also a great place to watch the sky. For a double-whammy, we say that you come around sunset, then hang out while the sky gets dark. Sure, it might take a few hours, but the view is worth it.

So there you have it, stargazers! Get ready to witness a dazzling show this summer.

-

Health24 hours ago

Prosperity Message From Jake – VIP

-

Business24 hours ago

WealthGenix

-

News24 hours ago

News24 hours agoBrandon Moreno to face Amir Albazi in new main event of UFC Edmonton card

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoChukwu on target as Canadian women thump Fiji 9-0 at FIFA U-20 World Cup in Colombia

-

Sports24 hours ago

Sports24 hours agoUS Open: Navarro’s first Grand Slam semifinal will be against Sabalenka. Taylor Fritz wins, too

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoAfghan refugee pleads no contest to 2 murders in case that shocked Albuquerque’s Muslim community

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoPope has packed first full day in Indonesia with visits to president, clergy in a test of stamina

-

News6 hours ago

News6 hours ago‘The deal is done:’ NDP Leader pulls out of supply and confidence deal with Liberals