Science

NASA Solidifies Planning to Deorbit ISS in 2031 – SpacePolicyOnline.com

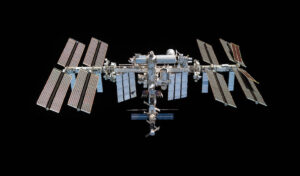

A month after formally announcing plans to extend operations of the International Space Station to 2030, NASA is making clear that is the end of the road. A new update to its ISS transition plan spells out how that end will play out, with the orbit gradually lowered until the football-field size facility reenters and any surviving pieces fall into the Pacific Ocean in January 2031. After that, NASA will buy whatever human spaceflight services it needs in low Earth orbit from companies expected to be operating their own space stations by then.

In the 2017 NASA Transition Authorization Act (P.L. 115-10), Congress required NASA to submit a transition plan explaining how it will meet its needs for human spaceflight research in LEO after ISS ends. For years the agency’s goal has been to facilitate the emergence of a commercial LEO economy that includes privately built and operated space stations with NASA as one of many customers using them instead of building another government-owned facility.

The law called for the first transition report in December 2017 with updates every two years through 2023. The original version was released a little late, on March 30, 2018, and this one, issued January 31, is NASA’s first update, almost four years later.

A lot has happened in between affecting NASA’s future human presence in LEO as the agency shifts its focus to returning astronauts to the Moon and going on to Mars.

For example, in 2020 SpaceX’s Crew Dragon restored the U.S. capability to launch people into orbit after nine years of dependence on Russia following the end of the space shuttle program. In 2021, ISS celebrated 21 years of permanent human occupancy, a testament to the strength of the partnership among the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada and 11 European countries that has weathered dramatic terrestrial geopolitical changes so far unscathed. Over the past several years, NASA has embraced public-private partnerships for a wide range of human spaceflight activities including successors to ISS. It signed a contract with Axiom Space in 2020 to add a commercial module to the ISS that later will detach and become a free-flying facility, and just two months ago chose three companies, Blue Origin, Nanoracks, and Northrop Grumman, to design commercial space stations for its Commercial LEO Destinations initiative.

The updated transition report works from the assumption that ISS will last until 2030, hopefully giving one or more of those companies enough time to design, build and launch something to replace at least some of its capabilities.

In the 2017 law, the United States committed to operating ISS at least through 2024. Congressional attempts to pass a new NASA authorization bill and extend that to 2030 have not succeeded, but on December 31, the Biden Administration gave its approval to do just that. A White House commitment isn’t quite as solid as a law, but it is enough for negotiations with the other partners to commence in earnest to get their agreement.

But the ISS is old. The first modules were launched in 1998. The updated transition report asserts the U.S. On-Orbit Segment (USOS) and the Functional Cargo Block (also known as FGB or Zarya), which was built by Russia but at U.S. expense and thereby counts as a U.S. module, are in good enough shape to make it to 2030. The report says Russia has certified the modules it owns through 2024 and “will begin work on analyzing extension through 2030.” Nagging leaks in one part of the Russian segment so far have thwarted attempts to seal them. NASA and its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, insist they pose no danger to the crew, but if nothing else they illustrate the aging problem.

Former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine warned the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee last October there is no guarantee the ISS will make it 2030, pushing back on the notion that it might last even longer.

NASA’s bottom line in this report is that “While the ISS will not last forever, NASA expects to be able to operate it safely through 2030.”

Then it will be deorbited. This report lays out that end-of-life process in more detail than in the past. Notionally three Russian Progress cargo spacecraft will be used to lower the ISS’s altitude until it reenters through the Earth’s atmosphere. Reentry is nominally targeted for January 2031 with any pieces that survive the fiery trip falling into the South Pacific Uninhabited Area around Point Nemo.

At 420 Metric Tons, ISS will be the largest structure to make a reentry. Russia’s Mir space station, which operated from 1986-2001, was about 130 MT when it made a controlled reentry into the Pacific on March 23, 2001. The first U.S. space station, Skylab, hosted crews in 1973 and 1974. The approximately 72 MT spacecraft made an uncontrolled reentry in 1979 spreading debris over western Australia and the Indian Ocean. Other space stations launched by the Soviet Union prior to 1986 and more recently by China that have reentered were smaller, though some were still quite sizeable. No one has been injured in any of these reentries.

Not only is ISS old, but it is expensive to operate, about $3 billion a year for NASA. That is another motivation for terminating it although NASA will still need to pay companies to use their facilities.

Congress asked NASA to provide cost estimates in the transition plan for operating the ISS through 2024, 2028 and 2030. In the 2018 report, it showed specific costs for Operations and Maintenance (O&M), research, crew and cargo, and labor and travel.

This time it does not give any detail, showing only a “sand chart.”

NASA declined to provide any more information, telling SpacePolicyOnline.com by email that “the detailed numbers are not available for public release as they are pre-decisional and procurement sensitive.”

Congress asked NASA to provide an estimate of the deorbit costs and while that item is included in the sand chart, its corresponding monetary value is obscure.

Similarly, the amount of annual cost savings NASA expects to realize by terminating ISS and shifting to commercial services is difficult to quantify based only on that chart. However, Phil McAlister, Director of NASA’s Commercial Spaceflight Division, told a NASA advisory committee meeting on January 19 that NASA estimates it will be about $1.3 million in 2031, the first year, and “if all things go as planned, it will go up to as high as $1.8 billion.”

Getting from here to there will require NASA funding to encourage the commercial sector to invest. After two years of providing only one-tenth of the $150 million requested by the agency for the Commercial LEO Development (CLD) program, Congress appears poised to support it more robustly this year.

NASA requested $101 million for FY2022. In July, the House Appropriations Committee included $45 million for CLD in the FY2022 Commerce-Justice-Science bill that funds NASA. While less than half the request, it is almost three times the $17 million appropriated in FY2021. In October, the Senate Appropriations Committee approved the full $101 million noting NASA had “finally” offered a rationale and roadmap for the program.

Further action on FY2022 appropriations remains stalled, however. NASA is operating under a Continuing Resolution (CR) that holds the agency at its FY2021 level for now.

Last Updated: Feb 06, 2022 1:50 pm ET

Science

SpaceX launch marks 300th successful booster landing – Phys.org

SpaceX sent up the 30th launch from the Space Coast for the year on the evening of April 23, a mission that also featured the company’s 300th successful booster recovery.

A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 23 of SpaceX’s Starlink internet satellites blasted off at 6:17 p.m. Eastern time from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch Complex 40.

The first-stage booster set a milestone of the 300th time a Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy booster made a successful recovery landing, and the 270th time SpaceX has reflown a booster.

This particular booster made its ninth trip to space, a resume that includes one human spaceflight, Crew-6. It made its latest recovery landing downrange on the droneship Just Read the Instructions in the Atlantic Ocean.

The company’s first successful booster recovery came in December 2015, and it has not had a failed booster landing since February 2021.

The current record holder for flights flew 11 days ago making its 20th trip off the launch pad.

SpaceX has been responsible for all but two of the launches this year from either Kennedy Space Center or Cape Canaveral with United Launch Alliance having launched the other two.

SpaceX could knock out more launches before the end of the month, putting the Space Coast on pace to hit more than 90 by the end of the year, but the rate of launches by SpaceX is also set to pick up for the remainder of the year with some turnaround times at the Cape’s SLC-40 coming in less than three days.

That could amp up frequency so the Space Coast could surpass 100 launches before the end of the year, with the majority coming from SpaceX. It hosted 72 launches in 2023.

More launches from ULA are on tap as well, though, including the May 6 launch atop an Atlas V rocket of the Boeing CST-100 Starliner with a pair of NASA astronauts to the International Space Station.

ULA is also preparing for the second launch ever of its new Vulcan Centaur rocket, which recently received its second Blue Origin BE-4 engine and is just waiting on the payload, Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser spacecraft, to make its way to the Space Coast.

Blue Origin has its own rocket it wants to launch this year as well, with New Glenn making its debut as early as September, according to SLD 45’s range manifest.

2024 Orlando Sentinel. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Citation:

SpaceX launch marks 300th successful booster landing (2024, April 24)

retrieved 24 April 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-04-spacex-300th-successful-booster.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Science

Wildlife Wednesday: loons are suffering as water clarity diminishes – Canadian Geographic

The common loon, that icon of northern wilderness, is under threat from climate change due to declining water clarity. Published earlier this month in the journal Ecology, a study conducted by biologists from Chapman University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in the U.S. has demonstrated the first clear evidence of an effect of climate change on this species whose distinct call is so tied to the soundscape of Canada’s lakes and wetlands.

Through the course of their research, the scientists found that July rainfall results in reduced July water clarify in loon territories in Northern Wisconsin. In turn, this makes it difficult for adult loons to find and capture their prey — mainly small fish — underwater, meaning they are unable to meet their chicks’ metabolic needs. Undernourished, the chicks face higher mortality rates. The consistent foraging techniques used by loons across their range means this impact is likely echoed wherever they are found — from Alaska to Canada to Iceland.

The researchers used Landsat imagery to find that there has been a 25-year consistent decline in water clarity, and during this period, body weights of adult loon and chicks alike have also declined. With July being the month of most rapid growth in young loons, the study also pinpointed water clarity in July as being the greatest predictor of loon body weight.

One explanation for why heavier rainfall leads to reduced water clarity is the rain might carry dissolved organic matter into lakes from adjacent streams and shoreline areas. Lawn fertilizers, pet waste and septic system leaks may also be to blame.

The researchers, led by Chapman University professor Walter Piper, hope to use these insights to further conservation efforts for this bird Piper describes as both “so beloved and so poorly understood.”

Return of the king

Science

Giant prehistoric salmon had tusk-like teeth for defence, building nests

|

|

The artwork and publicity materials showcasing a giant salmon that lived five million years ago were ready to go to promote a new exhibit, when the discovery of two fossilized skulls immediately changed what researchers knew about the fish.

Initial fossil discoveries of the 2.7-metre-long salmon in Oregon in the 1970s were incomplete and had led researchers to mistakenly suggest the fish had fang-like teeth.

It was dubbed the “sabre-toothed salmon” and became a kind of mascot for the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon, says researcher Edward Davis.

But then came discovery of two skulls in 2014.

Davis, a member of the team that found the skulls, says it wasn’t until they got back to the lab that he realized the significance of the discovery that has led to the renaming of the fish in a new, peer-reviewed study.

“There were these two skulls staring at me with sideways teeth,” says Davis, an associate professor in the department of earth sciences at the university.

In that position, the tusk-like teeth could not have been used for biting, he says.

“That was definitely a surprising moment,” says Davis, who serves as director of the Condon Fossil Collection at the university’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

“I realized that all of the artwork and all of the publicity materials and bumper stickers and buttons and T-shirts we had just made two months prior, for the new exhibit, were all out of date,” he says with a laugh.

Davis is co-author of the new study in the journal PLOS One, which renames the giant fish the “spike-toothed salmon.”

It says the salmon used the tusk-like spikes for building nests to spawn, and as defence mechanisms against predators and other salmon.

The salmon lived about five million years ago at a time when Earth was transitioning from warmer to relatively cooler conditions, Davis says.

It’s hard to know exactly why the relatives of today’s sockeye went extinct, but Davis says the cooler conditions would have affected the productivity of the Pacific Ocean and the amount of rain feeding rivers that served as their spawning areas.

Another co-author, Brian Sidlauskas, says a fish the size of the spike-toothed salmon must have been targeted by predators such as killer whales or sharks.

“I like to think … it’s almost like a sledgehammer, these salmon swinging their head back and forth in order to fend off things that might want to feast on them,” he says.

Sidlauskas says analysis by the lead author of the paper, Kerin Claeson, found both male and female salmon had the “multi-functional” spike-tooth feature.

“That’s part of our reason for hypothesizing that this tooth is multi-functional … It could easily be for digging out nests,” he says.

“Think about how big the (nest) would have to be for an animal of this size, and then carving it out in what’s probably pretty shallow water; and so having an extra digging tool attached to your head could be really useful.”

Sidlauskas says the giant salmon help researchers understand the boundaries of what’s possible with the evolution of salmon, but they also capture the human imagination and a sense of wonder about what’s possible on Earth.

“I think it helps us value a little more what we do still have, or I hope that it does. That animal is no longer with us, but it is a product of the same biosphere that sustains us.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 24, 2024.

Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press

-

Art23 hours ago

The unmissable events taking place during London’s Digital Art Week

-

Politics18 hours ago

Politics18 hours agoOpinion: Fear the politicization of pensions, no matter the politician

-

Economy23 hours ago

German Business Outlook Hits One-Year High as Economy Heals

-

Science17 hours ago

Science17 hours agoNASA Celebrates As 1977’s Voyager 1 Phones Home At Last

-

Media17 hours ago

B.C. puts online harms bill on hold after agreement with social media companies

-

Business16 hours ago

Oil Firms Doubtful Trans Mountain Pipeline Will Start Full Service by May 1st

-

Politics17 hours ago

Politics17 hours agoPecker’s Trump Trial Testimony Is a Lesson in Power Politics

-

News19 hours ago

Provincial audit turns up more than 40 medical clinics advertising membership fees