Art

Police busts, porn cinemas and glory holes: the wild art of sexual outlaw Dean Sameshima – The Guardian

[ad_1]

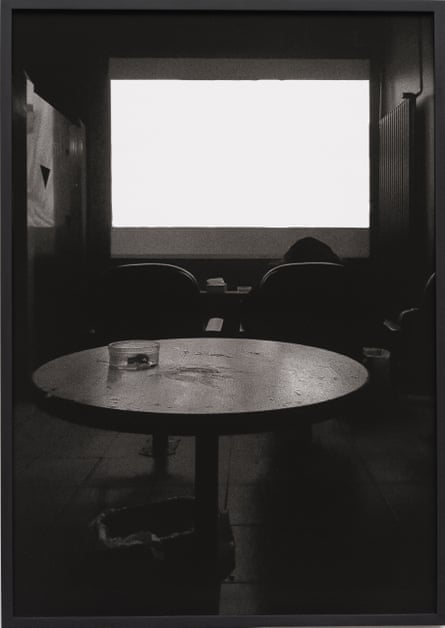

Veer to your left in the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale and you’ll come across a painting bearing the words: “Anonymous Homosexual.” Round the corner, there’s a row of black-and-white pictures showing transfixed male viewers, seen from the back, watching a screen. Ah, the magic of cinema, you might think – except for all the boxes of tissues, indicating that this is a particular kind of cinema.

This is part of Being Alone, a body of work by the artist Dean Sameshima, an expanded version of which is also on show at Soft Opening in London. Sitting in an outdoor cafe in the Giardini, the Biennale’s main space, Sameshima says he visited five gay porn cinemas in Berlin, his adopted home, over a number of years, and decided to commemorate a culture that is disappearing due to hook-up apps. His pictures are enigmatic, melancholy and yet somehow seductive, the loitering silhouettes and shining screen expressing loneliness, escapism and perhaps a kind of defiance against the expectations of society.

Though some people may regard going to porn cinemas as tragic and sleazy, Sameshima doesn’t see it that way. Since his teens in California, he’s cruised bookshops, cinemas and public toilets, finding them much more congenial than the mainstream gay world. On Grindr, he says, no one is interested in meeting a 53-year-old man of Asian heritage. “If you ask other queer Asians, especially of my generation, the gay community has been horrible,” he says. “Horrible to our self-esteem, to everything.”

Sameshima grew up in Southern California. He didn’t enjoy school, but his imagination was fired by music (on Instagram, he often posts old tickets he has kept from gigs he loved, on the anniversary of the date he saw them). His first concert was David Bowie, the Go-Gos and Madness in 1983, but his main passion was for British punk bands like Crass and GBH, though he dabbled in goth too. Music and clothes (“I had pointy skull boots”) allowed Sameshima to express his feelings of being different without drawing attention to his sexuality. He was particularly inhibited because, he says, “Aids had started to happen. As soon as you came home from school, it was the first thing on every news channel.”

Once Sameshima was 17, he got a car and was able to explore farther afield. In his late teens, inspired by the magazine Details, he became fascinated by high fashion. “I was like, ‘Margiela, what is this?’ That was like punk and goth to me.” This led him into the worlds of art and photography. Another route was via a famous LA bookstore. “Someone told me, ‘If you want to meet people like yourself, go to Circus of Books.’I thought, ‘Maybe there are meetings for people like me?’ But it turned out to be cruising.”

As a recent Netflix documentary confirmed, the gay clientele of Circus of Books used to make eye contact while perusing the shelves, then go to a nearby car park known as Vaseline Alley. Nonetheless, Sameshima spent enough time actually reading to realise that there were entire books of homoerotic photography by people like Herb Ritts, Bruce Weber, and his favourite Joel-Peter Witkin. He realised there could be a space for him to express himself through his camera – he was already taking photographs at the gigs he was attending. Another inspiration was The Sexual Outlaw, a gay rights polemic by the writer John Rechy written in 1977. “On the first page it says, ‘For all the anonymous outlaws.’ And I remember thinking, ‘He’s talking to me.’”

Sameshima got a job in the bookshop at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in LA, the ideal place for him to continue delving into his artistic and literary obsessions. In 1992 he was busted by the LAPD while cruising for sex in a public toilet, six years before the same fate befell George Michael. In 2016, Sameshima made enormous paintings out of his police documents and exhibited them in a gallery. When his parents came to the opening, it was the first time they’d realised he’d been arrested. He had been so scared of their reaction that he dealt with the whole thing alone.

Given the way gay cruisers were often publicly shamed, this may have been a wise strategy. “In 2012, on Tumblr,” Sameshima says, “there was an article about a bust in Manhattan Beach [in California] at one of the popular bathrooms, and they posted the full names and portraits of all the men. I just thought, ‘If that had happened to me …’ This is why people kill themselves, because they can’t be out. And so that’s what triggered me to want to do these monumental paintings of my record of getting busted, to pay homage to those people, and to anyone else who had to go through that, and to hold it with pride.”

In fact, Sameshima is now so at ease with his cruising self that he has a tattoo of a glory hole – openings punched in the walls of toilet cubicles, allowing the men on either side to have sex with each other. (He also did a series of photographs of them, called Erdbeermund.) The artist is more ambivalent about another tattoo that reads “How Soon is Now” in homage to the Smiths, given Morrissey’s recent politics. “Johnny Marr is still OK,” he says. “And he co-wrote How Soon Is Now. Well, that’s how I justify it.”

Sameshima did his artistic training at CalArts, and by the turn of the century was being noticed for work that drew on his immersion in fashion and gay subculture; re-photographed images from Prada ads “like landscapes”, or a series in which he went to Britpop clubs in LA and photographed handsome young men going wild on the dancefloor. (Sameshima was a huge Britpop fan: “Jarvis Cocker was my ideal man. I was obsessed!”) He was represented by the hip gallery Peres Projects, but his work never came anywhere near the mainstream. “I’ve always felt overlooked,” he says. “Even by the power gays in the art world.”

Around 2007, Sameshima seemed to stop working. Why? “Drugs and alcohol,” he says without hesitation. “I’ve always had a problem with addiction, but in 2006 I got blackout drunk, and got a DUI charge” – driving under the influence. Given his dangerous propensity to get behind the wheel while severely intoxicated, his gallerist Javier Peres persuaded him to move to Berlin, where a car was far less essential. Once there, however, his self-destructive tendencies ramped up, and he spent much of the time drinking alone in his flat. “I became a morning drinker,” Sameshima says. “I would do tequila shots to wake myself up.”

He finally got sober in 2010, and this week celebrated 14 years of being alcohol and drug-free. Returning to art was “like learning how to walk again”, as drinking “really eased my mind … it shut up the self-criticalness”. Before Sameshima felt ready to make work again, he started a successful Tumblr account on which he posted “stuff from my archive, things I’ve held on to – flyers, sex club membership cards”.

He also started making T-shirts printed with fragments of esoteric gay culture: the title of Roland Barthes’ book A Lover’s Discourse, or the cover of Tearoom Trade, a study of gay sex in public toilets by the sociologist (and priest) Laud Humphreys. Sameshima would sell the T-shirts on Etsy, and they gathered a cult following, until producing and posting them became too much hassle: “It was detracting from my studio practice.”

Nevertheless, the work Anonymous Faggots, Sameshima’s showstopping painting in the Venice Arsenale, reveals a through-line between his various projects: he used to produce a T-shirt printed with the word Faggots, and the distinctive typeface on both T-shirt and artwork is taken from the cover of a 1978 book by Larry Kramer, a satire on New York’s hedonistic gay in-crowd. (The “Anonymous”, meanwhile, comes from Alcoholics Anonymous.)

The people in Sameshima’s porn cinema pictures are not the in-crowd, and neither is the man photographing them. “I don’t mind being alone,” he says. “I love doing stuff alone. I’m a loner, owning it.” Yet the pictures also have a certain sense of camaraderie, not least because in Venice they are hung alongside other photographs taken in gay porn cinemas in the 70s, by the Colombian artist Miguel Ángel Rojas, speaking to a kind of tradition and commonality, across time and in different countries, even in the most furtive and marginal places.

Both artists commemorate those who feel at home in the shadowy, sticky spaces of a sex cinema, perhaps the only places they can be themselves. “It’s about celebrating and acknowledging that we still exist,” Sameshima says. “People who don’t identify with a gay community, people who don’t even identify as queer. In-between people.”

[ad_2]

Source link

Art

Turner: Art, Industry and Nostalgia review – Fighting Temeraire sets Tyneside ablaze – The Guardian

[ad_1]

JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire might be the most famous painting in London’s National Gallery and in 2005 was voted The Greatest Painting in Britain, but it’s hardly cool. Its heady atmosphere of patriotic pride and supercharged sentiment is the quintessence of the traditional image the gallery is trying to slough off in its bicentenary year. So while Caravaggio and Van Gogh are at the heart of celebrations in London, The Fighting Temeraire has been, as it were, dragged off by steam tug to be quietly moored on the Tyne.

Yet instead of just borrowing this unfashionable masterpiece, as part of a project entitled National Treasures that has sent 12 NG paintings out and about, Newcastle’s Laing Gallery has built an ambitious and moving exhibition around it.

This lovely show demonstrates precisely why Turner’s 1839 depiction of a ghostly giant of the age of sail being pulled to its final breakup by a newfangled steam tug is just so tearjerkingly evocative of Britain’s past – especially Newcastle’s. In fact, one fascinating find here is a model of a Victorian steam tug built in Newcastle. These low-slung working boats, mounted with a steam engine that drove two paddle wheels, were a Tyneside speciality – it was the Tyne-built steam tugs, London and the Samson, that pulled HMS Temeraire to the breaker’s yard.

Now the steam tugs too belong to a rusting past, as does so much of the north-east’s shipbuilding industry. The show includes powerful black-and-white photographs by Chris Killip of the last days of Tyneside supertanker-building in the 1970s. In one, children play on a terraced street corner, dwarfed by a half-built tanker looming in fog; in another, workers look tiny below the monster propeller of the ship they’re building. By 1979, this Tyne industry would vanish. “I didn’t know at the time that it was going to end as quickly as it did,” a wall text quotes him as saying.

This north-eastern perspective puts the nostalgia of Turner’s Fighting Temeraire in a smoky new light. It also makes visual sense. The sublime disparities in scale in Killip’s photographs capture, just as they mourn, the great industrial yards and their massive creations, all taking you straight back to Turner. The show includes the artist’s mighty 1818 watercolour A First Rate Taking on Stores, which depicts a colossal Royal Navy ship surrounded by smaller boats. Turner dwells on the fortress-like immensity of its gun-studded side, which makes the little boats seem like toys. Looking at this, you see why the navy in this era was said to defend Britain with “wooden walls”.

What’s incredible is how Turner can communicate the stateliness of this nautical behemoth in watercolours on a little sheet of paper. His genius can be baffling. He knows the way water moves and how clouds flow with such intimacy he can unleash their forces like a magician controlling the weather. In an early sketch of Dunstanburgh Castle in Northumberland, he adds fishing boats caught in a swirling channel against the castle’s seaside cliffs.

Turner also acknowledged the horror in the battle of Trafalgar. His awesome oil sketch of the 1805 confrontation – in which Nelson led his ships straight into the French fleet in a gory, foolhardy triumph that destroyed Napoleon’s pretensions to sea power – concentrates on the men, British as well as French, trying to survive in the sea after losing their ships. Behind them, the battle is a confusion of smoke and sails. Who’s winning? Is anyone?

The Temeraire fought alongside Nelson’s HMS Victory. Built at Chatham dockyard in Kent from more than 5,000 oak trees, it served in the Napoleonic wars and was specially praised for its actions at Trafalgar. A detailed 1805 model of the Temeraire is on show, laboriously made from animal bone by French prisoners. The Victory is preserved as a national monument, while the Temeraire’s fighting days were forgotten and it was used as a floating barracks on the Thames for naval recruits. By 1838, it was time to drag the old hulk to be scrapped.

It all leaves you primed to look at Turner’s painting of this vessel as never before. A pale ghost ship can be seen towering in the evening light, already vanishing, its richly wrought prow a wonder from a lost age. Such ships existed, Turner is saying, as did the people who sailed and fought on them. But here now is the cheeky, brash, steam-driven tug whose paddles chop the water into spuming waves. The river is spookily still, a burnished mirror for a sun that’s determined to give the Temeraire an appropriate sendoff, with rays exploding in a twilight display of crimson, gold and scarlet. It’s fire in the sky that echoes the long-silenced guns of Trafalgar.

Patriotic? Sentimental? Hell yeah. But The Fighting Temeraire is really a painting about what it is to be outmoded in an ever-changing industrial world – for a sailing ship, a 1970s shipyard worker, or indeed an artist. Like the Temeraire, Turner saw impossible changes in his lifetime. He witnessed the Industrial Revolution, saw sail give way to steam and even caught the birth of photography. A letter from him is on display in which he refuses to lend the work – let alone sell it – “for any price”. The mysterious intensity of The Fighting Temeraire and his attachment to it come from his identification with the doomed ship.

Turner kept this painting with him until he died and left it to the National Gallery. This fine exhibition frees a great work from cliche by taking a national anthem and turning it into a Springsteen rustbelt ballad.

[ad_2]

Source link

Art

Turner: Art, Industry and Nostalgia review – Fighting Temeraire sets Tyneside ablaze – The Guardian

[ad_1]

JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire might be the most famous painting in London’s National Gallery and in 2005 was voted The Greatest Painting in Britain, but it’s hardly cool. Its heady atmosphere of patriotic pride and supercharged sentiment is the quintessence of the traditional image the gallery is trying to slough off in its bicentenary year. So while Caravaggio and Van Gogh are at the heart of celebrations in London, The Fighting Temeraire has been, as it were, dragged off by steam tug to be quietly moored on the Tyne.

Yet instead of just borrowing this unfashionable masterpiece, as part of a project entitled National Treasures that has sent 12 NG paintings out and about, Newcastle’s Laing Gallery has built an ambitious and moving exhibition around it.

This lovely show demonstrates precisely why Turner’s 1839 depiction of a ghostly giant of the age of sail being pulled to its final breakup by a newfangled steam tug is just so tearjerkingly evocative of Britain’s past – especially Newcastle’s. In fact, one fascinating find here is a model of a Victorian steam tug built in Newcastle. These low-slung working boats, mounted with a steam engine that drove two paddle wheels, were a Tyneside speciality – it was the Tyne-built steam tugs, London and the Samson, that pulled HMS Temeraire to the breaker’s yard.

Now the steam tugs too belong to a rusting past, as does so much of the north-east’s shipbuilding industry. The show includes powerful black-and-white photographs by Chris Killip of the last days of Tyneside supertanker-building in the 1970s. In one, children play on a terraced street corner, dwarfed by a half-built tanker looming in fog; in another, workers look tiny below the monster propeller of the ship they’re building. By 1979, this Tyne industry would vanish. “I didn’t know at the time that it was going to end as quickly as it did,” a wall text quotes him as saying.

This north-eastern perspective puts the nostalgia of Turner’s Fighting Temeraire in a smoky new light. It also makes visual sense. The sublime disparities in scale in Killip’s photographs capture, just as they mourn, the great industrial yards and their massive creations, all taking you straight back to Turner. The show includes the artist’s mighty 1818 watercolour A First Rate Taking on Stores, which depicts a colossal Royal Navy ship surrounded by smaller boats. Turner dwells on the fortress-like immensity of its gun-studded side, which makes the little boats seem like toys. Looking at this, you see why the navy in this era was said to defend Britain with “wooden walls”.

What’s incredible is how Turner can communicate the stateliness of this nautical behemoth in watercolours on a little sheet of paper. His genius can be baffling. He knows the way water moves and how clouds flow with such intimacy he can unleash their forces like a magician controlling the weather. In an early sketch of Dunstanburgh Castle in Northumberland, he adds fishing boats caught in a swirling channel against the castle’s seaside cliffs.

Turner also acknowledged the horror in the battle of Trafalgar. His awesome oil sketch of the 1805 confrontation – in which Nelson led his ships straight into the French fleet in a gory, foolhardy triumph that destroyed Napoleon’s pretensions to sea power – concentrates on the men, British as well as French, trying to survive in the sea after losing their ships. Behind them, the battle is a confusion of smoke and sails. Who’s winning? Is anyone?

The Temeraire fought alongside Nelson’s HMS Victory. Built at Chatham dockyard in Kent from more than 5,000 oak trees, it served in the Napoleonic wars and was specially praised for its actions at Trafalgar. A detailed 1805 model of the Temeraire is on show, laboriously made from animal bone by French prisoners. The Victory is preserved as a national monument, while the Temeraire’s fighting days were forgotten and it was used as a floating barracks on the Thames for naval recruits. By 1838, it was time to drag the old hulk to be scrapped.

It all leaves you primed to look at Turner’s painting of this vessel as never before. A pale ghost ship can be seen towering in the evening light, already vanishing, its richly wrought prow a wonder from a lost age. Such ships existed, Turner is saying, as did the people who sailed and fought on them. But here now is the cheeky, brash, steam-driven tug whose paddles chop the water into spuming waves. The river is spookily still, a burnished mirror for a sun that’s determined to give the Temeraire an appropriate sendoff, with rays exploding in a twilight display of crimson, gold and scarlet. It’s fire in the sky that echoes the long-silenced guns of Trafalgar.

Patriotic? Sentimental? Hell yeah. But The Fighting Temeraire is really a painting about what it is to be outmoded in an ever-changing industrial world – for a sailing ship, a 1970s shipyard worker, or indeed an artist. Like the Temeraire, Turner saw impossible changes in his lifetime. He witnessed the Industrial Revolution, saw sail give way to steam and even caught the birth of photography. A letter from him is on display in which he refuses to lend the work – let alone sell it – “for any price”. The mysterious intensity of The Fighting Temeraire and his attachment to it come from his identification with the doomed ship.

Turner kept this painting with him until he died and left it to the National Gallery. This fine exhibition frees a great work from cliche by taking a national anthem and turning it into a Springsteen rustbelt ballad.

[ad_2]

Source link

Art

Turner: Art, Industry and Nostalgia review – Fighting Temeraire sets Tyneside ablaze – The Guardian

[ad_1]

JMW Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire might be the most famous painting in London’s National Gallery and in 2005 was voted The Greatest Painting in Britain, but it’s hardly cool. Its heady atmosphere of patriotic pride and supercharged sentiment is the quintessence of the traditional image the gallery is trying to slough off in its bicentenary year. So while Caravaggio and Van Gogh are at the heart of celebrations in London, The Fighting Temeraire has been, as it were, dragged off by steam tug to be quietly moored on the Tyne.

Yet instead of just borrowing this unfashionable masterpiece, as part of a project entitled National Treasures that has sent 12 NG paintings out and about, Newcastle’s Laing Gallery has built an ambitious and moving exhibition around it.

This lovely show demonstrates precisely why Turner’s 1839 depiction of a ghostly giant of the age of sail being pulled to its final breakup by a newfangled steam tug is just so tearjerkingly evocative of Britain’s past – especially Newcastle’s. In fact, one fascinating find here is a model of a Victorian steam tug built in Newcastle. These low-slung working boats, mounted with a steam engine that drove two paddle wheels, were a Tyneside speciality – it was the Tyne-built steam tugs, London and the Samson, that pulled HMS Temeraire to the breaker’s yard.

Now the steam tugs too belong to a rusting past, as does so much of the north-east’s shipbuilding industry. The show includes powerful black-and-white photographs by Chris Killip of the last days of Tyneside supertanker-building in the 1970s. In one, children play on a terraced street corner, dwarfed by a half-built tanker looming in fog; in another, workers look tiny below the monster propeller of the ship they’re building. By 1979, this Tyne industry would vanish. “I didn’t know at the time that it was going to end as quickly as it did,” a wall text quotes him as saying.

This north-eastern perspective puts the nostalgia of Turner’s Fighting Temeraire in a smoky new light. It also makes visual sense. The sublime disparities in scale in Killip’s photographs capture, just as they mourn, the great industrial yards and their massive creations, all taking you straight back to Turner. The show includes the artist’s mighty 1818 watercolour A First Rate Taking on Stores, which depicts a colossal Royal Navy ship surrounded by smaller boats. Turner dwells on the fortress-like immensity of its gun-studded side, which makes the little boats seem like toys. Looking at this, you see why the navy in this era was said to defend Britain with “wooden walls”.

What’s incredible is how Turner can communicate the stateliness of this nautical behemoth in watercolours on a little sheet of paper. His genius can be baffling. He knows the way water moves and how clouds flow with such intimacy he can unleash their forces like a magician controlling the weather. In an early sketch of Dunstanburgh Castle in Northumberland, he adds fishing boats caught in a swirling channel against the castle’s seaside cliffs.

Turner also acknowledged the horror in the battle of Trafalgar. His awesome oil sketch of the 1805 confrontation – in which Nelson led his ships straight into the French fleet in a gory, foolhardy triumph that destroyed Napoleon’s pretensions to sea power – concentrates on the men, British as well as French, trying to survive in the sea after losing their ships. Behind them, the battle is a confusion of smoke and sails. Who’s winning? Is anyone?

The Temeraire fought alongside Nelson’s HMS Victory. Built at Chatham dockyard in Kent from more than 5,000 oak trees, it served in the Napoleonic wars and was specially praised for its actions at Trafalgar. A detailed 1805 model of the Temeraire is on show, laboriously made from animal bone by French prisoners. The Victory is preserved as a national monument, while the Temeraire’s fighting days were forgotten and it was used as a floating barracks on the Thames for naval recruits. By 1838, it was time to drag the old hulk to be scrapped.

It all leaves you primed to look at Turner’s painting of this vessel as never before. A pale ghost ship can be seen towering in the evening light, already vanishing, its richly wrought prow a wonder from a lost age. Such ships existed, Turner is saying, as did the people who sailed and fought on them. But here now is the cheeky, brash, steam-driven tug whose paddles chop the water into spuming waves. The river is spookily still, a burnished mirror for a sun that’s determined to give the Temeraire an appropriate sendoff, with rays exploding in a twilight display of crimson, gold and scarlet. It’s fire in the sky that echoes the long-silenced guns of Trafalgar.

Patriotic? Sentimental? Hell yeah. But The Fighting Temeraire is really a painting about what it is to be outmoded in an ever-changing industrial world – for a sailing ship, a 1970s shipyard worker, or indeed an artist. Like the Temeraire, Turner saw impossible changes in his lifetime. He witnessed the Industrial Revolution, saw sail give way to steam and even caught the birth of photography. A letter from him is on display in which he refuses to lend the work – let alone sell it – “for any price”. The mysterious intensity of The Fighting Temeraire and his attachment to it come from his identification with the doomed ship.

Turner kept this painting with him until he died and left it to the National Gallery. This fine exhibition frees a great work from cliche by taking a national anthem and turning it into a Springsteen rustbelt ballad.

[ad_2]

Source link