Science

Remains of glacier found near Mars equator

(CNN) — The remains of a glacier have been found near the Martian equator, suggesting that some form of water could still exist in a region on the red planet where humans may one day land.

The ice mass is no longer there, but scientists spotted telltale remains among other mineral deposits near Mars’ equatorial region. The deposits there usually contain light-colored sulfate salts.

When scientists took a closer look, they recognized the features of a glacier, including ridges called moraines — debris deposited or pushed by a moving glacier. The research team also spotted crevasse fields, or deep wedge-shaped openings that form inside glaciers.

The findings were shared Wednesday at the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

“What we’ve found is not ice, but a salt deposit with the detailed morphologic features of a glacier,” lead study author Dr. Pascal Lee, a senior planetary scientist with the SETI Institute and the Mars Institute, said in a statement.

“What we think happened here is that salt formed on top of a glacier while preserving the shape of the ice below, down to details like crevasse fields and moraine bands.”

The researchers believe the glacier was 3.7 miles (6 kilometers) long and 2.5 miles (about 4 kilometers) wide, with an elevation between 0.8 to 1.1 miles (1.3 to 1.7 kilometers).

Volcanic activity creates protective layer

Scientists have an idea of how the imprint of the glacier came to be, based on evidence of volcanic material in the region. When mixtures of volcanic ash, lava and volcanic glass called pumice react with water, a hard, crusty salt layer can form.

“This region of Mars has a history of volcanic activity. And where some of the volcanic materials came in contact with glacier ice, chemical reactions would have taken place at the boundary between the two to form a hardened layer of sulfate salts,” said study coauthor Sourabh Shubham, a doctoral student of geology at the University of Maryland, College Park, in a statement.

“This is the most likely explanation for the hydrated and hydroxylated sulfates we observe in this light-toned deposit.”

Geologically young surface ice near equator

The volcanic material likely eroded over time, revealing the salty layer that captured an imprint of the glacier ice and its distinctive features, said study coauthor John Schutt, a geologist at the Mars Institute and an icefield guide in the Arctic and Antarctica.

Mars has a thin atmosphere, which allows space rocks to collide regularly with the planet’s surface. But the fine, detailed features of the glacier still remain largely undisturbed in the salt deposit, which leads researchers to believe it’s relatively “young.”

The study authors said they think the glacier existed during the Mars Amazonian geologic period, which began 2.9 billion years ago and remains ongoing.

“We’ve known about glacial activity on Mars at many locations, including near the equator in the more distant past. And we’ve known about recent glacial activity on Mars, but so far, only at higher latitudes,” Lee said. “A relatively young relict glacier in this location tells us that Mars experienced surface ice in recent times, even near the equator, which is new.”

The researchers don’t know if any ice remains beneath the deposit.

“Water ice is, at present, not stable at the very surface of Mars near the equator at these elevations,” Lee said. “So, it’s not surprising that we’re not detecting any water ice at the surface. It is possible that all the glacier’s water ice has sublimated away by now. But there’s also a chance that some of it might still be protected at shallow depth under the sulfate salts.”

Potential for shallow ice pockets

During the study, the team also looked at ancient ice islands called salars in Bolivia’s Altiplano salt flats in South America. Blankets of salts have protected old glacier ice from melting or evaporating, leading the researchers to think that a similar scenario might have occurred on Mars.

Next, the researchers want to determine if any ice remains from the glacier, and if so, how much is present at shallow depths beneath the salt deposits. If this particular salt deposit is protecting ice, it’s possible that other pockets of ice exist nearby.

Orbiters circling the planet have shown deposits of ice at the frigid Martian poles, but if water in any form exists at the warmer equatorial lower latitudes, it could have implications for our understanding of the red planet’s history and potential habitability — and future exploration by humans.

“The desire to land humans at a location where they might be able to extract water ice from the ground has been pushing mission planners to consider higher latitude sites,” Lee said. “But the latter environments are typically colder and more challenging for humans and robots. If there were equatorial locations where ice might be found at shallow depth, then we’d have the best of both environments: warmer conditions for human exploration and still access to ice.”

Science

Las Vegas Aces Rookie Kate Martin Suffers Ankle Injury in Game Against Chicago Sky

Las Vegas Aces rookie Kate Martin had to be helped off the floor and taken to the locker room after suffering an apparent ankle injury in the first quarter of Tuesday night’s game against the Chicago Sky.

Late in the first quarter, Martin was pushing the ball up the court when she appeared to twist her ankle and lost her balance. The rookie was in serious pain, lying on the floor before eventually being helped off. Her entire team came out in support, and although she managed to put some pressure on the leg, she was taken to the locker room for further evaluation.

Martin returned to the team’s bench late in the second quarter but was ruled out for the remainder of the game.

“Kate Martin is awesome. Kate Martin picks up things so quickly, she’s an amazing sponge,” Aces guard Kelsey Plum said of the rookie during the preseason. “I think (coach) Becky (Hammon) nicknamed her Kate ‘Money’ Martin. I think that’s gonna stick. And when I say ‘money,’ it’s not just about scoring and stuff, she’s just in the right place at the right time. She just makes people better. And that’s what Becky values, that’s what our coaching staff values and that’s why she’s gonna be a great asset to our team.”

Las Vegas selected Martin in the second round of the 2024 WNBA Draft. She was coming off the best season of her collegiate career at Iowa, where she averaged 13.1 points, 6.8 rebounds, and 2.3 assists per game during the 2023-24 campaign. Martin’s integration into the Aces organization has been seamless, with her quickly earning the respect and admiration of her teammates and coaches.

The team and fans alike are hoping for a speedy recovery for Martin, whose contributions have been vital to the Aces’ performance this season.

Science

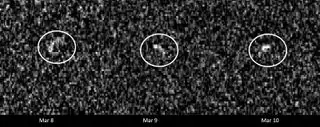

Asteroid Apophis will visit Earth in 2029, and this European satellite will be along for the ride

The European Space Agency is fast-tracking a new mission called Ramses, which will fly to near-Earth asteroid 99942 Apophis and join the space rock in 2029 when it comes very close to our planet — closer even than the region where geosynchronous satellites sit.

Ramses is short for Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety and, as its name suggests, is the next phase in humanity’s efforts to learn more about near-Earth asteroids (NEOs) and how we might deflect them should one ever be discovered on a collision course with planet Earth.

In order to launch in time to rendezvous with Apophis in February 2029, scientists at the European Space Agency have been given permission to start planning Ramses even before the multinational space agency officially adopts the mission. The sanctioning and appropriation of funding for the Ramses mission will hopefully take place at ESA’s Ministerial Council meeting (involving representatives from each of ESA’s member states) in November of 2025. To arrive at Apophis in February 2029, launch would have to take place in April 2028, the agency says.

This is a big deal because large asteroids don’t come this close to Earth very often. It is thus scientifically precious that, on April 13, 2029, Apophis will pass within 19,794 miles (31,860 kilometers) of Earth. For comparison, geosynchronous orbit is 22,236 miles (35,786 km) above Earth’s surface. Such close fly-bys by asteroids hundreds of meters across (Apophis is about 1,230 feet, or 375 meters, across) only occur on average once every 5,000 to 10,000 years. Miss this one, and we’ve got a long time to wait for the next.

When Apophis was discovered in 2004, it was for a short time the most dangerous asteroid known, being classified as having the potential to impact with Earth possibly in 2029, 2036, or 2068. Should an asteroid of its size strike Earth, it could gouge out a crater several kilometers across and devastate a country with shock waves, flash heating and earth tremors. If it crashed down in the ocean, it could send a towering tsunami to devastate coastlines in multiple countries.

Over time, as our knowledge of Apophis’ orbit became more refined, however, the risk of impact greatly went down. Radar observations of the asteroid in March of 2021 reduced the uncertainty in Apophis’ orbit from hundreds of kilometers to just a few kilometers, finally removing any lingering worries about an impact — at least for the next 100 years. (Beyond 100 years, asteroid orbits can become too unpredictable to plot with any accuracy, but there’s currently no suggestion that an impact will occur after 100 years.) So, Earth is expected to be perfectly safe in 2029 when Apophis comes through. Still, scientists want to see how Apophis responds by coming so close to Earth and entering our planet’s gravitational field.

“There is still so much we have yet to learn about asteroids but, until now, we have had to travel deep into the solar system to study them and perform experiments ourselves to interact with their surface,” said Patrick Michel, who is the Director of Research at CNRS at Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice, France, in a statement. “Nature is bringing one to us and conducting the experiment itself. All we need to do is watch as Apophis is stretched and squeezed by strong tidal forces that may trigger landslides and other disturbances and reveal new material from beneath the surface.”

By arriving at Apophis before the asteroid’s close encounter with Earth, and sticking with it throughout the flyby and beyond, Ramses will be in prime position to conduct before-and-after surveys to see how Apophis reacts to Earth. By looking for disturbances Earth’s gravitational tidal forces trigger on the asteroid’s surface, Ramses will be able to learn about Apophis’ internal structure, density, porosity and composition, all of which are characteristics that we would need to first understand before considering how best to deflect a similar asteroid were one ever found to be on a collision course with our world.

Besides assisting in protecting Earth, learning about Apophis will give scientists further insights into how similar asteroids formed in the early solar system, and, in the process, how planets (including Earth) formed out of the same material.

One way we already know Earth will affect Apophis is by changing its orbit. Currently, Apophis is categorized as an Aten-type asteroid, which is what we call the class of near-Earth objects that have a shorter orbit around the sun than Earth does. Apophis currently gets as far as 0.92 astronomical units (137.6 million km, or 85.5 million miles) from the sun. However, our planet will give Apophis a gravitational nudge that will enlarge its orbit to 1.1 astronomical units (164.6 million km, or 102 million miles), such that its orbital period becomes longer than Earth’s.

It will then be classed as an Apollo-type asteroid.

Ramses won’t be alone in tracking Apophis. NASA has repurposed their OSIRIS-REx mission, which returned a sample from another near-Earth asteroid, 101955 Bennu, in 2023. However, the spacecraft, renamed OSIRIS-APEX (Apophis Explorer), won’t arrive at the asteroid until April 23, 2029, ten days after the close encounter with Earth. OSIRIS-APEX will initially perform a flyby of Apophis at a distance of about 2,500 miles (4,000 km) from the object, then return in June that year to settle into orbit around Apophis for an 18-month mission.

Related Stories:

Furthermore, the European Space Agency still plans on launching its Hera spacecraft in October 2024 to follow-up on the DART mission to the double asteroid Didymos and Dimorphos. DART impacted the latter in a test of kinetic impactor capabilities for potentially changing a hazardous asteroid’s orbit around our planet. Hera will survey the binary asteroid system and observe the crater made by DART’s sacrifice to gain a better understanding of Dimorphos’ structure and composition post-impact, so that we can place the results in context.

The more near-Earth asteroids like Dimorphos and Apophis that we study, the greater that context becomes. Perhaps, one day, the understanding that we have gained from these missions will indeed save our planet.

Science

McMaster Astronomy grad student takes a star turn in Killarney Provincial Park

Astronomy PhD candidate Veronika Dornan served as the astronomer in residence at Killarney Provincial Park. She’ll be back again in October when the nights are longer (and bug free). Dornan has delivered dozens of talks and shows at the W.J. McCallion Planetarium and in the community. (Photos by Veronika Dornan)

BY Jay Robb, Faculty of Science

July 16, 2024

Veronika Dornan followed up the April 8 total solar eclipse with another awe-inspiring celestial moment.

This time, the astronomy PhD candidate wasn’t cheering alongside thousands of people at McMaster — she was alone with a telescope in the heart of Killarney Provincial Park just before midnight.

Dornan had the park’s telescope pointed at one of the hundreds of globular star clusters that make up the Milky Way. She was seeing light from thousands of stars that had travelled more than 10,000 years to reach the Earth.

This time there was no cheering: All she could say was a quiet “wow”.

Dornan drove five hours north to spend a week at Killarney Park as the astronomer in residence. part of an outreach program run by the park in collaboration with the Allan I. Carswell Observatory at York University.

Dornan applied because the program combines her two favourite things — astronomy and the great outdoors. While she’s a lifelong camper, hiker and canoeist, it was her first trip to Killarney.

Bruce Waters, who’s taught astronomy to the public since 1981 and co-founded Stars over Killarney, warned Dornan that once she went to the park, she wouldn’t want to go anywhere else.

The park lived up to the hype. Everywhere she looked was like a painting, something “a certain Group of Seven had already thought many times over.”

She spent her days hiking the Granite Ridge, Crack and Chikanishing trails and kayaking on George Lake. At night, she went stargazing with campers — or at least tried to. The weather didn’t cooperate most evenings — instead of looking through the park’s two domed telescopes, Dornan improvised and gave talks in the amphitheatre beneath cloudy skies.

Dornan has delivered dozens of talks over the years in McMaster’s W.J. McCallion Planetarium and out in the community, but “it’s a bit more complicated when you’re talking about the stars while at the same time fighting for your life against swarms of bugs.”

When the campers called it a night and the clouds parted, Dornan spent hours observing the stars. “I seriously messed up my sleep schedule.”

She also gave astrophotography a try during her residency, capturing images of the Ring Nebula and the Great Hercules Cluster.

“People assume astronomers take their own photos. I needed quite a lot of guidance for how to take the images. It took a while to fiddle with the image properties, but I got my images.”

Dornan’s been invited back for another week-long residency in bug-free October, when longer nights offer more opportunities to explore and photograph the final frontier.

She’s aiming to defend her PhD thesis early next summer, then build a career that continues to combine research and outreach.

“Research leads to new discoveries which gives you exciting things to talk about. And if you’re not connecting with the public then what’s the point of doing research?”

-

News7 hours ago

News7 hours agoAfter grind of MLS regular season, Toronto FC looks forward to Leagues Cup challenge

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoCanadaNewsMedia news July 26, 2024: B.C. crews wary of winds boosting wildfires

-

News13 hours ago

News13 hours agoOntario expanding access to RSV vaccines for young children, pregnant women

-

News8 hours ago

News8 hours agoIn President Milei’s sit-down with Macron, Argentina says the leaders get past soccer chant fallout

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoPeople should stay inside, filter indoor air amid wildfire smoke, respirologist says

-

News15 hours ago

News15 hours agoFederal grand jury charges short seller Andrew Left in $16M stock manipulation scheme

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoFrench train lines hit by ‘malicious acts’ disrupting traffic ahead of Olympics, rail company says

-

News13 hours ago

News13 hours agoWork continues to clean second motor oil spill in river near Montreal