Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

|

|

If you’re in the market for ghoulish ceramic heads or colorful collages of gay sex among off-duty soldiers, a new digital art platform has you covered.

Its goal: to uplift contemporary queer art in all its forms — and make it easier than ever to market it. “QAP.digital believes queer art needs to be kept alive not only in the name of much needed diversity, but also in the name of perpetual creativity,” the website reads. “QAP.digital is a space to celebrate queer art, and to help it live, flourish, thrive.”

Erdem and Ergul say they keep an eye out for art that goes beyond just addressing queerness in terms of gender and sexuality. They are interested in all the ways queerness serves as a force of creativity in life — in form, style, production and presentation.

“This is the moment when we first thought a commercial platform might create an alternative source of income to queer artists,” Erdem and Ergul, who both identify as queer, told CNN in an email.

“When the straight cis white artist is free to roam as they please, only dwell on aesthetic considerations, come up with pure abstractions, why does the queer artist have to be limited to speaking about queer issues in a recognizable way to tick some boxes?”

With hyper-realistic silicone models of tongues, ears, and breasts jutting out of brass wires like bouquets, Radage’s work, she explains, is about dismembering things to unpack what it means to be human, and dissect the intersection of neurodiversity and queerness. Credit: Alicia Radage

“I love my work being in the flesh and people being in the same space and time,” Radage told CNN. “And also that is incredibly draining on resources, time, energy, money… What I can do though, is spend loads of time in my studio making a piece of work, photograph it and put it in (an) online gallery. More people are going to be able to see it and engage with it,” she said.

Radage’s experiences with QAP.digital, and with Erdem and Ergul, have been a welcome change of pace from the wider art market — they are emotionally invested, she told CNN, but always professional. Their support allows her to create freely, while still allowing her to profit from her work, she explained. (Radage has yet to see any of her work sold through QAP.digital, however.)

A piece on QAP.digital by the artist Nicky Broekhuysen, whose work focuses on the binary code. Credit: Nicky Broekhuysen

“It’s fantastic having a safe space for queer people,” Rolls-Bentley, who identifies as queer, said. “But a space where people who don’t identify as queer can come and celebrate and learn and share experiences with queer people is a really powerful thing that we need.”

But while Rolls-Bentley argues there is still merit in carving out space for queer artists in bigger museums, auction houses, and galleries,” Erdem and Ergul have different priorities.

“Most galleries do not understand queer artists’ specific needs. To most artists, feeling that you genuinely value their work, not just by assigning a price to it, but by understanding exactly where they are coming from with their work, is much more important than how much they sell.”

Top image: The landing page at QAP.Digital, which rotates regularly through artwork and pieces within the platform’s collections.

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

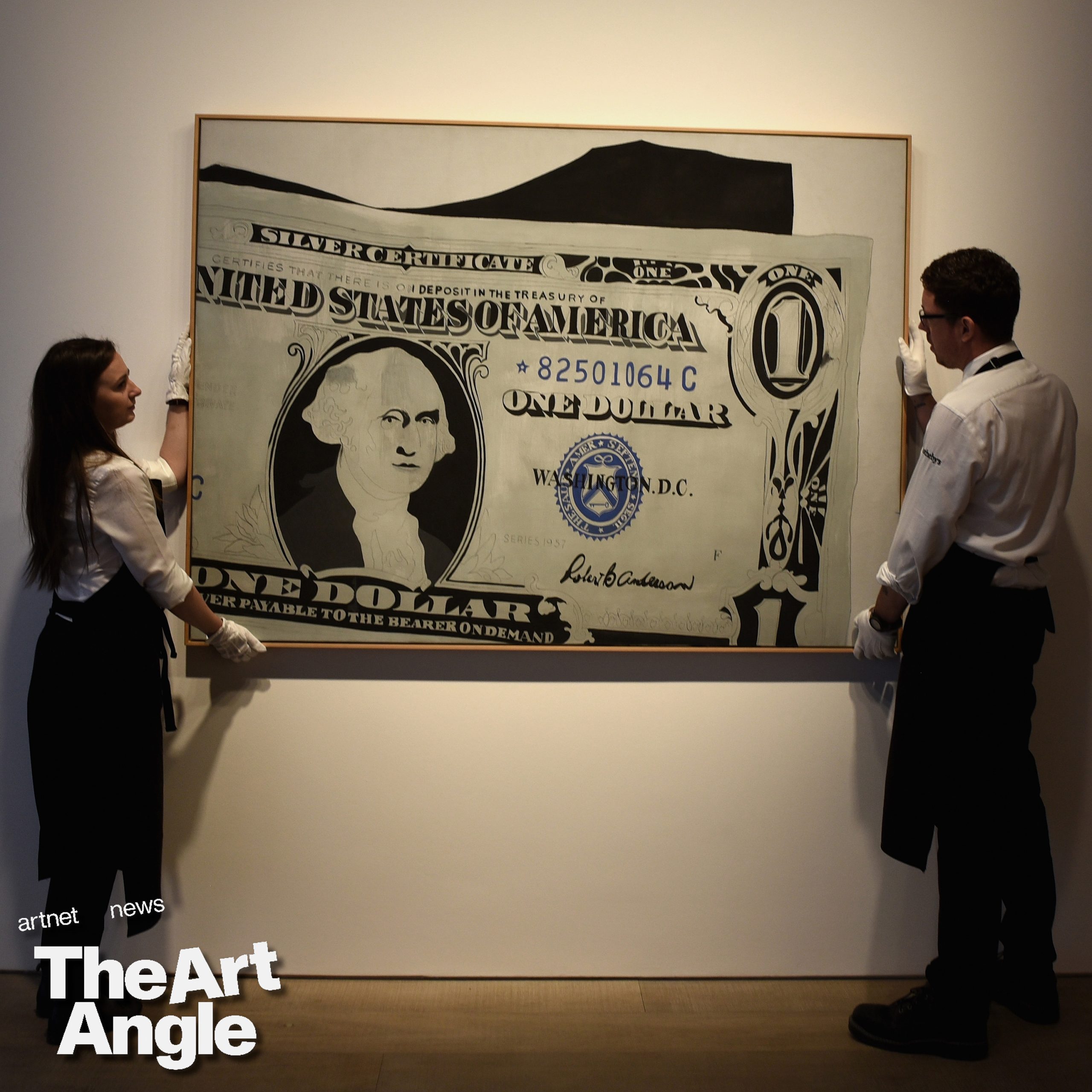

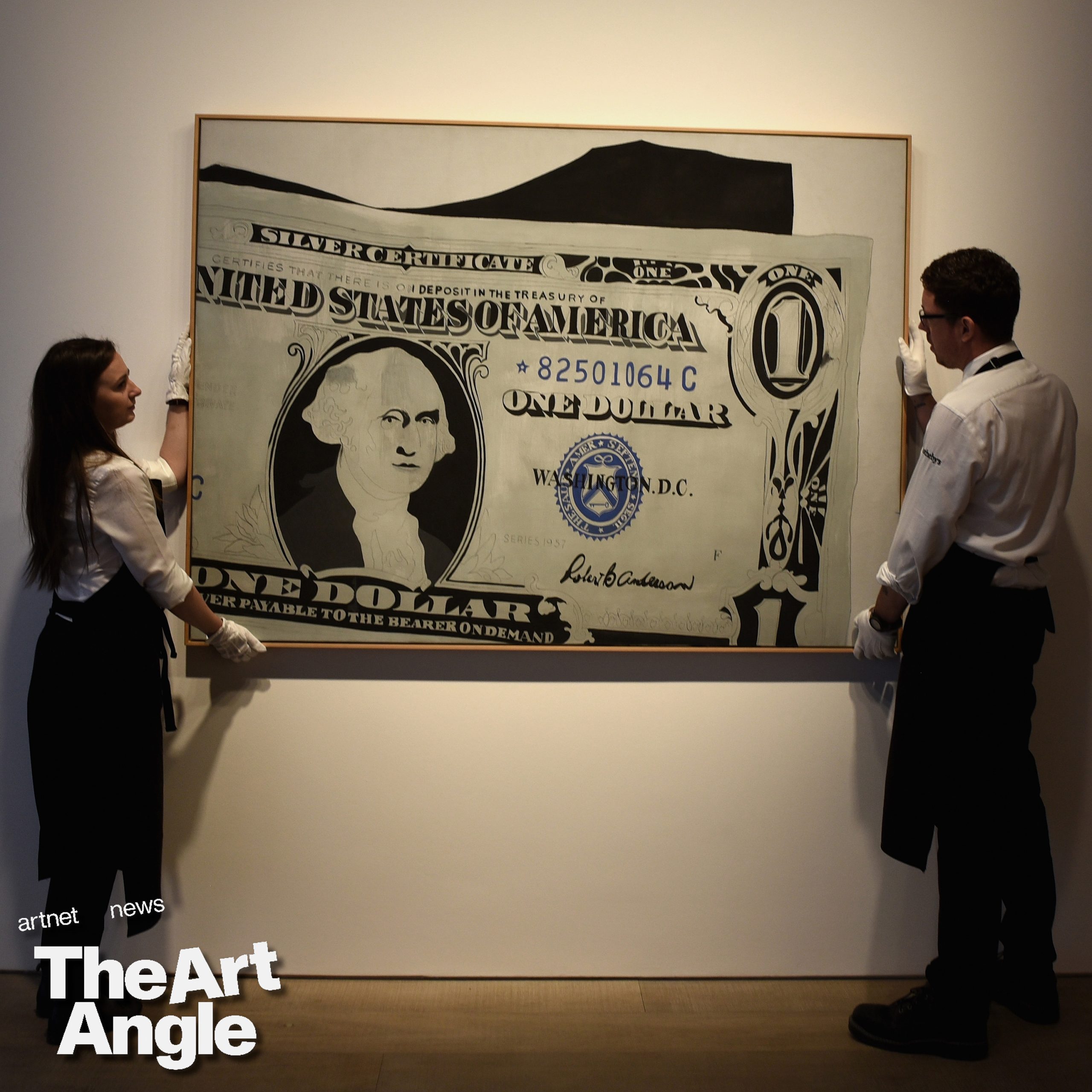

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Digital artist Sam Spratt is living the artist’s dream. This week, he celebrated the opening of “The Monument Game,” his first-ever art show. But it wasn’t a group show in some DIY space in New York, where he is based, like so many artists typically start out, but a solo exhibition in Venice, during the art world’s biggest event of the year—the Venice Biennale. How did Spratt–a virtually unknown name in the art world–make such a tremendous leap? With a little help from his friends, of course, including Ryan Zurrer, the venture capitalist turned digital art champion.

“Something the capital ‘A’ art world doesn’t recognize is the power of the collective, it sometimes leans into the cult of the individual,” Ryan Zurrer told ARTnews during a preview of the opening. “But this show is supported by the entire community around Sam.”

Spratt’s Venice exhibition was put on by 1OF1 Collection, a “collecting club” set up by Zurrer to nurture digital artists working in the NFT space. Since its launch in 2021, 1OF1 has been uniquely successful in bridging the gap between the art world and the Web3 community. Last year, 1OF1 and the RFC Art Collection gifted Anadol’s Unsupervised – Machine Hallucinations – MoMA to the museum, after nearly a year on view in the Gund Lobby. Zurrer also arranged the first museum presentations of Beeple’s HUMAN ONE, a seven-foot-tall kinetic sculpture based on video works, showing it first at Castello di Rivoli in Italy and the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, before sending it to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

With “The Monument Game,” Zurrer is once again placing digitally native art at the center of the art world. While Anadol and Beeple had large cultural footprints prior to Zurrer’s patronage, Spratt is far earlier in his career. But, what attracted Zurrer, he said, was the artist’s shrewd approach to building a dedicated, participatory audience for his work. He did so by making his art a game.

“When I first started looking at NFTs, I spent a long time just figuring out who the players were,” Spratt told ARTnews. “The auctions were like stories in themselves, I could see people’s friends bidding, almost ceremonially, to give the auction some energy, and then other people would come in, and it would get competitive, emotional.”

Spratt released his first three NFTs on the platform SuperRare in October 2021. The sale of those works, the first from his series LUCI, was accompanied by a giveaway of a free NFT to every person who put in a bid. Zurrer had been one of those underbidders (for the work Birth of Luci). While Spratt said the derivative NFTs were basically worthless, he wanted to give something back to each bidder. Zurrer, and others it seems, appreciated the gesture and Spratt quickly gained a following in the Web3 space. The offerings he gave, called Skulls of Luci, became Sam’s dedicated collectors that now go by The Council of Luci. 47 editions were given out and Spratt held back three.

All the works from LUCI are on view at the Docks Cantiere Cucchini, a short walk from the Arsenale, past a rocking boat that doubles as a fruit and vegetable market and over a wooden bridge. Though NFTs typically bring to mind glitching screens and monkey cartoons (ala Bored Ape Yacht Club), the ten works on view depict apes in a detailed, painterly style and emit a soft glow. Taking cues from photography installations, 1OF1 ditched screens in favor of prints mounted on lightboxes.

“We don’t want it to look like a Best Buy in here,” said Zurrer.

Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

Each work represents a chapter in a fantasy world that Spratt dreamed up. Though there’s no book of lore to refer to, there seems to be some Planet of the Apes story at play in which an intelligent ape lives alongside humans, babies, and ape-human hybrids. Spratt received an education in oil painting at Savannah College of Art and Design and he credits that technical training with his ability to bring warmth and detail to the digital works. He and the team often say that his art historical references harken to Renaissance and Baroque art, though the aesthetics—to my eye—seem to pull from commercial illustration and concept art. That isn’t too surprising given that this was the environment that Spratt started off in after graduating SCAD in 2010.

“After school I was confronted with the reality that for a digital artist the only path was commercial,” Spratt said.

He did quite well on that path, producing album covers for Childish Gambino, Janelle Monae, and Kid Cudi and bagging clients like Marvel, StreetEasy, and Netflix. Spratt also enjoys a huge audience of fans who have followed him as he’s migrated from Facebook to Tumblr to Twitter and Instagram, posting his hyper-realistic fan-art on each platform. Despite the apparent success, Spratt spoke of the work with bitterness.

“I was a gun for hire. A mimic, hired to be 30% me and 70% someone else,” he said.

Spratt’s personal life blew up when he turned 30 and he traced some of the mistakes he made in his relationships with the fact that he had spent so much of his career “telling other people’s stories.” NFTs seemed like a way out of commercial illustration and a way into an original art practice.

For his latest piece in the LUCI series, Spratt digitally painted a massive landscape set in this ape-human world titled The Monument Game. For the piece, Spratt initially sold NFTs that would turn 209 collectors into “players” (since another edition of 256 NFTs was given to the Council to “curate” new champions”). Each player would then be allowed to make an observation about the painting. The Council of Luci would vote on which three observations were best, and those three Players would receive one of the Skulls of Luci NFTs that Spratt held back. By creating these tiers of engagement, with his Council and player structure, Spratt pushes digital collectors to give the kind of care to his work that more traditional collectors do.

A work at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

“Jeff Koons said that the average person looks at a work of art for twenty seconds,” Lukas Amacher, 1OF1’s Artistic Director and the curator of the show, told ARTnews. “Sam has found a way to get people to engage in his work for much longer.”

The game Spratt has designed for the Venice exhibition might seem too gamified to fit the art world’s notion of art, but as Amacher and Zurrer suggest, in the Web3 environment, value is built by finding alternative ways to create investment and attention in what are typically immaterial digital artifacts. And it’s working. Thus far, the LUCI series has generated $2 million in primary sales and about $4 million in additional secondary volume. The challenge now, as it has been for the past three years, is to see if art’s gatekeepers will take this work seriously.

At the presentation of The Monument Game in Venice, an observation deck, built by platform Nifty Gateway, sits in front of the mounted work. Participants can click on the painting on the screen and write down their observations of the work in front of them, no NFT required. The first observation came from star curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli and curator of Documenta 15: a tribute to art dealer Marian Goodman. The second was from Zurrer. Who’s next?

“Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” is on view until June 21 at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Take in improv comedy, art discussions and shows, locally-produced theatre and live instrumental or choral music.

Unseasonable snow this week isn’t slowing the arts down; nor should it hamper the enjoyment of events around town. Get out and take in a variety of comedy shows, art exhibitions and theatre this weekend.

1 — Laugh along with the Soaps

Article content

Saskatoon Soaps Improv Comedy presents We Love the ’90s. Return to the 1990s improv-style, complete with flannel, grunge and gangsta rap jokes coming faster than the old dial-up internet connection. The troupe performs live comedy based on audience suggestions, so be prepared with your classic references and ideas. The all-ages show is Friday at the Broadway Theatre at 8 p.m. Learn more at broadwaytheatre.ca.

Advertisement 2

Article content

2 — Chat with a local artist and take in an exhibition

The Ukrainian Museum of Canada presents an artist talk by its second artist in residence, Amalie Atkins. The Saskatoon-based artist discusses her residency and how her creative expression resonates with the history of Ukrainian heritage. The free event is Saturday at the museum at 3 p.m. Atkins’s exhibition will be on display through May 18. Learn more at umcnational.ca.

GlassArt showcases glasswork by members of the Saskatoon Glassworkers Guild. The annual show features unique works made through a variety of processes and techniques. Artists are in attendance and there will be some demonstrations. The exhibition runs Friday through Sunday in the Galleria at Innovation Place. Learn more at saskatoonglassworkersguild.org.

3 — Experience live, local theatre

Live Five Independent Theatre presents Bat Brains (or let’s explore mental illness with vampires), a new comedy by Sam Kruger and S.E. Grummett. Inspired by a months-long mental breakdown, the dark comedy follows Scud the vampire, who hasn’t left his house in 53 years. The arrival of an unexpected visitor launches Scud on a journey through his home, his mind and beyond. The show opens Friday and runs to April 28 at The Refinery. Learn more at ontheboards.ca.

Advertisement 3

Article content

4 — Sing along with a local choir

The Saskatoon Men’s Chorus presents the spring concert, Meetin’ Here Tonight. Enjoy gospel and classic favourites with special guests: bassist Bruce Wilkinson, baritone Adam Brookman and the Outlook Men’s Chorus. Sunday at Zion Lutheran Church at 2:30 p.m. Learn more at saskatoonmenschorus.ca.

Cecilian Singers present their spring concert, Come Sing with Me. The singers are joined by three guests: soprano Kelsey Ronn, violinist Wagner Barbosa and percussionist Darrell Bueckert. The concert is Sunday at Grosvenor Park United Church at 3 p.m. Learn more at ceciliansingers.ca.

5 — Listen to historic instruments

The University of Saskatchewan presents Rawlins Piano Trio, the final concert of the season in the Discovering the Amatis series. The chamber music performance features violinist Ioana Galu and cellist Sonja Kraus from the piano trio. They are joined by flutist Joey Zhuang and violinist Véronique Mathieu. Showcasing the historic Amati string instruments, the concert is Sunday at 3 p.m. in Convocation Hall at the U of S. Learn more at leadership.usask.ca.

Recommended from Editorial

With some online platforms blocking access to the news upon which you depend, our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark thestarphoenix.com and sign up for our newsletters here so we can keep you informed.

Article content

Auston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

Benjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

'Kingdom Come: Deliverance II' Revealed In Epic New Trailer And It Looks Incredible – Forbes

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

Comments