Economy

The Economic Cost of Its Errors Will Make the EU Wince: Eco Week – Bloomberg

[ad_1]

The European Union’s lost opportunity to shake off the coronavirus with swift vaccinations is likely to overshadow economic forecasts this week that may show a frustratingly slow recovery in 2021.

The European Commission has the uncomfortable task of revealing an outlook that will implicitly highlight the impact of the bloc’s delayed procurement of inoculations. Persisting lockdowns are probably costing the EU economy about 12 billion euros ($14 billion) per week in missing output, according to Bloomberg Economics.

It’s not clear if the executive will need to downgrade its prior euro-zone forecast for an incomplete rebound of 4.2% from 2020’s massive contraction. In any case, those predictions on Thursday will surely struggle to convey as much optimism as the Bank of England did last week when it confirmed the U.K.’s go-it-alone vaccine strategy is paying off materially on growth.

Herd Immunity Trajectory

Years required to inoculate 75% of the population with a two-dose vaccine

Source: Bloomberg’s Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker

Note: Herd immunity forecast at 70%-85% vaccination level

.chart-js display: none;

Aside from the political furor in Brussels over the EU’s faltering immunization push, the fallout may put the onus on officials in Frankfurt to determine if the euro region’s recovery is getting enough support. That might be a question for European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde to answer when she testifies to the bloc’s parliament on Monday.

What Bloomberg Economics Says:

“The spread of more transmissible strains of Covid-19 and a slow start to the vaccination campaigns means that it will take longer before containment measures can be lifted. While economies have adapted to this new environment, restrictions will continue to weigh on the outlook well into the first half of the year.”

–Maeva Cousin, euro-area economist

Elsewhere, Lagarde’s predecessor, Mario Draghi, may be sworn in as Italy’s next prime minister at the head of a technocrat government, and central banks in Russia, Sweden and Mexico set interest rates.

Central Bank Rate Decisions This Week

.chart-js display: none;

Click here for what happened last week and below is our wrap of what is coming up in the global economy.

U.S.

Investors in the U.S. will be watching out for the latest consumer-price data, to see if higher costs for some industries are finding their way to households. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell is also scheduled to speak Wednesday at the Economic Club of New York on the labor market.

Congressional committees are set to start crafting legislation this week on specific components of President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief plan after votes in the House and Senate Friday on a budget resolution for 2021.

Europe, Middle East, Africa

The U.K. economy probably kept growing in the fourth quarter, albeit at a weaker pace than the 16% rebound sustained in the prior three months. Economists anticipate a 0.5% expansion in gross domestic product for the period, a last spurt before new lockdowns brought activity to another crashing halt in recent weeks. Those data are due Friday.

Still Expanding

The U.K. economy probably kept growing in the final quarter of 2020

Source: ONS, Bloomberg survey of economists

.chart-js display: none;

As the BOE steers markets away from the idea that it might soon adopt negative rates in the U.K., a pioneering central bank that has already abandoned the policy is likely to keep borrowing costs at zero. Investors will likely focus on the Riksbank’s asset purchase program as vaccinations are seen gathering pace to help Sweden’s economy rebound.

Most economists expect Russian central bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina to keep rates on hold at her first policy meeting of the year on Friday, but rising inflation and ruble weakness might still prompt her to start hinting at an increase.

Serbia’s central bank also holds a rate meeting and is expected to keep the benchmark at a record low. In Romania, the parliament may debate and vote on a much-delayed 2021 state budget in the first major test for the country’s ruling coalition.

Ghana’s statistics office will release data on Wednesday that will probably show inflation remained close to the 10% top of the central bank’s target range. In South Africa, a report the same day will likely show business confidence remained muted in December and January after some Covid-19 restrictions were reimposed and power cuts resumed.

Asia

Data out Monday could show a shift in Japan’s remarkably low bankruptcy levels, as its renewed state of emergency puts more pressure on smaller businesses. Wage figures are expected to show a sharp fall on lower bonuses that could further weaken consumption.

New Bank of Japan board member Toyoaki Nakamura makes a debut speech Wednesday that will be closely scrutinized for clues over the BOJ’s policy review.

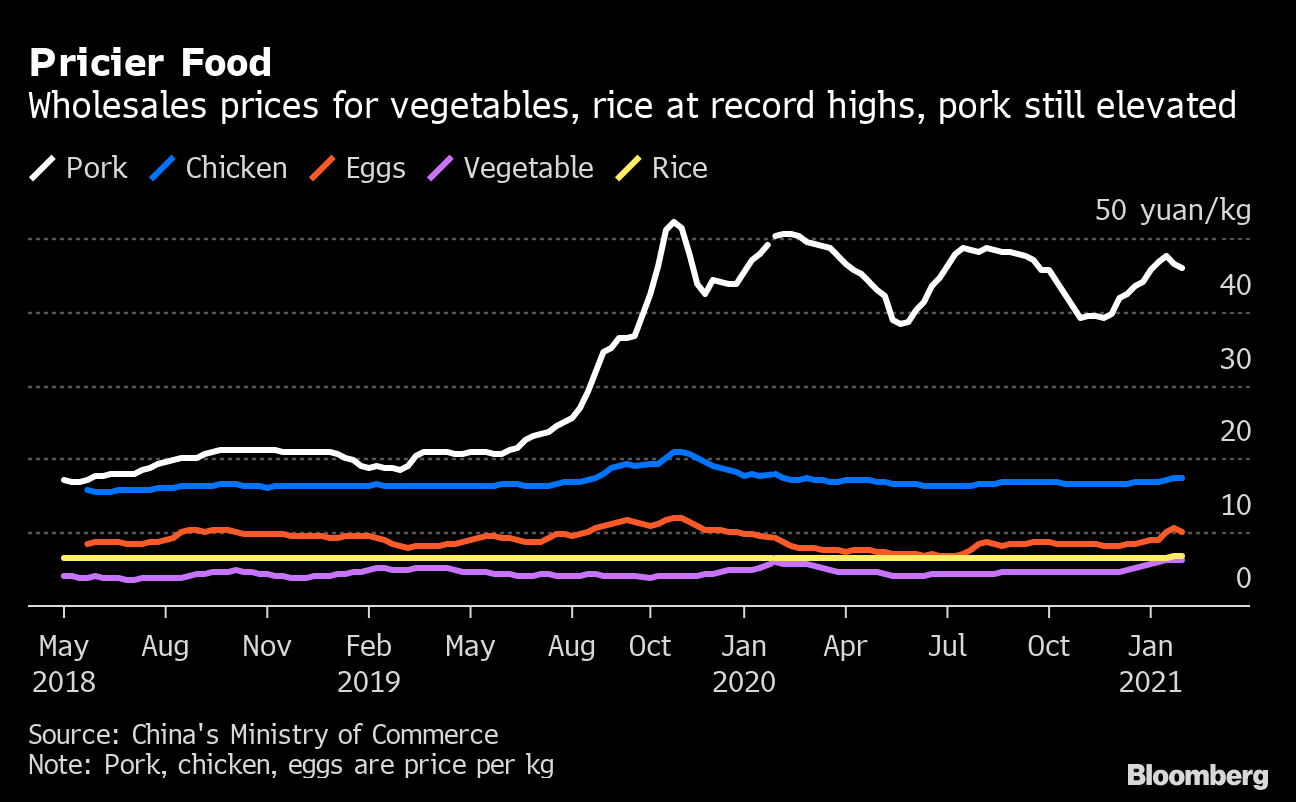

In China, inflation data due Wednesday are expected to show overall consumer prices fell slightly in January, although it may not feel that way for many people struggling with soaring food prices ahead of the Lunar New Year holiday that starts the next day.

Pricier Food

Wholesales prices for vegetables, rice at record highs, pork still elevated

Source: China’s Ministry of Commerce

Note: Pork, chicken, eggs are price per kg

.chart-js display: none;

On Thursday, Malaysia will report fourth quarter and full-year GDP numbers while interest rates are likely to be left on hold in the Philippines.

India’s CPI data for January, due on Friday, may reveal inflation remained in the central bank’s comfort zone for a second month.

Latin America

After a quiet 2020, inflation is back on Latin America’s agenda. Of the four countries reporting January data this week, the results from Chile and Argentina won’t surprise or influence policy, but those from Brazil and Mexico just might.

Heating Up

Brazilian inflation, key rate seen rising

Source: Estimates of analysts surveyed by Bloomberg.

.chart-js display: none;

Banco Central do Brasil would dearly like to hold at 2% next month, but accelerating price gains may force its hand, while analysts see some chance Banxico will look past slightly faster readings and cut its key rate to 4% Thursday.

The easing of lockdowns should flatter Colombia’s December retail sales result while a resurgence of the virus and wind-down of cash handouts should further deflate retailing and economic activity figures for Brazil.

Rough Patch

Mexico last posted a year-on-year rise in output in February 2019

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.

Note: December 2021 figures are median estimates.

.chart-js display: none;

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic knocked Mexico’s industrial sector flat. In the longer view, however, December will likely see a 21st consecutive negative year-on-year print, with February 2019 as lone positive reading under President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

Peru’s central bank on Thursday will all but certainly hold at 0.25% for a 10th month.

— With assistance by Peggy Collins, Robert Jameson, Benjamin Harvey, Alessandra Migliaccio, Malcolm Scott, and Alaa Shahine

[ad_2]

Source link

Economy

Burnett asks Biden how he is going to turn the economy around. He said he already has – CNN

[ad_1]

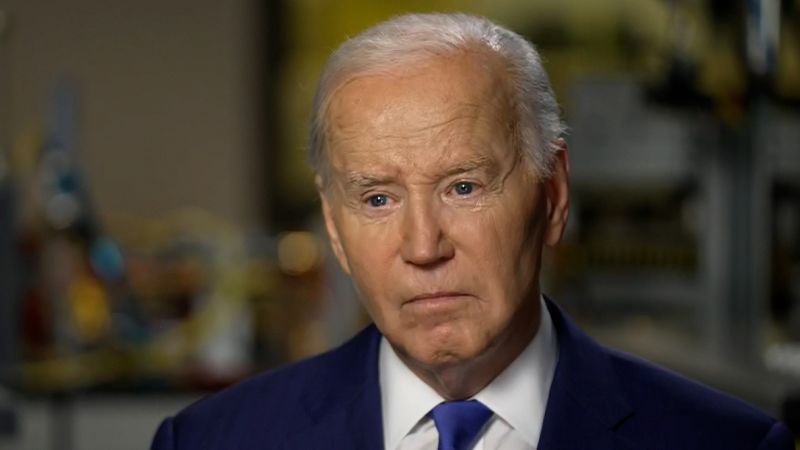

Burnett asks Biden how he is going to turn the economy around. He said he already has

CNN’s Erin Burnett asks President Joe Biden about how he is going to combat inflation and improve the economy before election day 2024.

[ad_2]

Source link

Economy

Burnett asks Biden how he is going to turn the economy around. He said he already has – CNN

[ad_1]

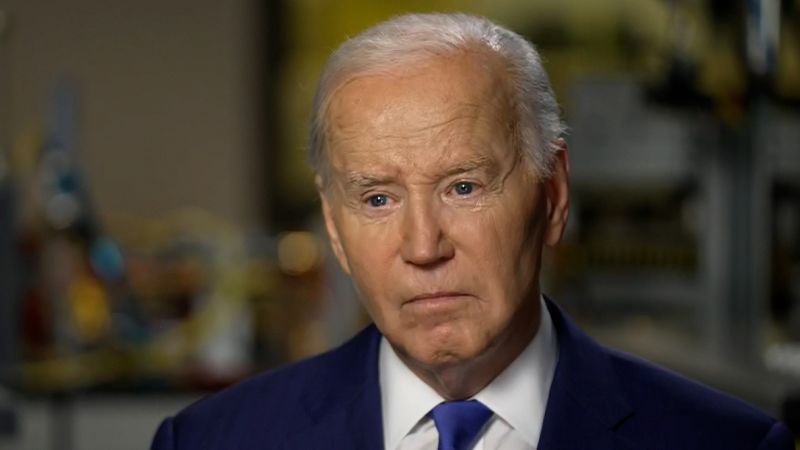

Burnett asks Biden how he is going to turn the economy around. He said he already has

CNN’s Erin Burnett asks President Joe Biden about how he is going to combat inflation and improve the economy before election day 2024.

[ad_2]

Source link

Economy

Opinion: The economy we have taken for granted is not coming back – The Globe and Mail

[ad_1]

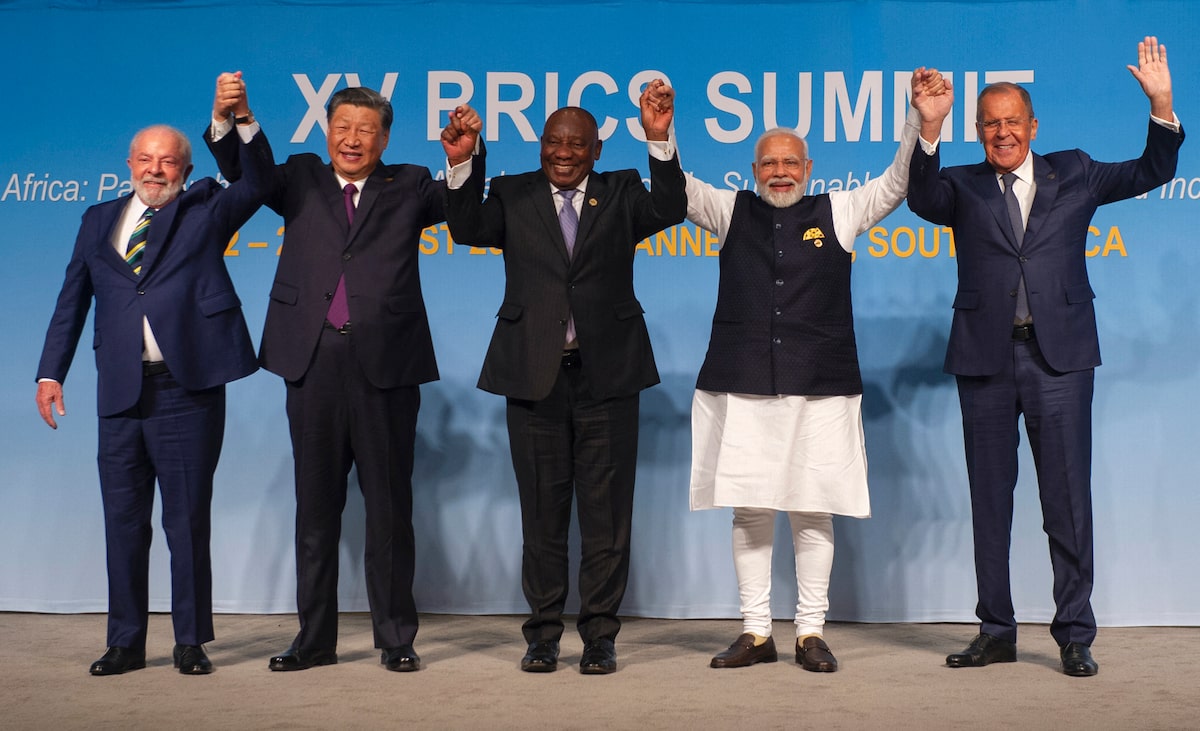

From the left: Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, China’s President Xi Jinping, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov raise their arms at the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa on Aug. 23, 2023.ALET PRETORIUS/The Canadian Press

Jeff Rubin is the former chief economist and chief strategist at CIBC World Markets. His latest book is A Map of the New Normal: How Inflation, War, and Sanctions Will Change Your World Forever, from which this essay is adapted.

In the early 1960s, only 4 per cent of countries were subject to economic sanctions imposed by either the United States or the United Nations, accounting for less than 4 per cent of global trade.

Today, 54 – a quarter of all the countries in the world – are subject to some form of sanctions, affecting almost a third of global GDP. And at the rate that sanctions are now being applied, it will soon be the majority of trade.

The world is engulfed in an ever-escalating global trade war. Virtually every day, new sanctions are being imposed, triggering reciprocal actions against Western goods.

Where will this lead? Can the West still win such wars, as it has done before? If not, what are the consequences of losing?

Along with sanctions has risen a new world order in which the United States and its NATO allies can no longer use their economic and military power to unilaterally dictate terms to the rest of the world.

A growing number of economic heavyweights in the developing world are joining America’s principal opponents, China and Russia, in the BRICS economic alliance, which includes once bitter enemies Saudi Arabia and Iran. Dozens more countries are lining up to join.

Together they are challenging the dominance of Western economic power on a scale not seen in a century. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the trade war over Ukraine, which began with Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

As BRICS membership grows, the reach of Western sanctions shrinks. Instead of isolating Russia as a pariah, sanctions have instead fractured the global economy into competing geopolitical blocs.

Russia itself is of course no stranger to Western sanctions. What U.S. President Joe Biden and his Western allies didn’t realize was that Russia had been busily sanctions-proofing its economy ever since it annexed Crimea back in 2014, if not before, in anticipation of economic reprisals from NATO countries.

And even more importantly, Western powers didn’t fully appreciate how the rest of the world, particularly the emerging Global South, had changed and the role it could play in taking the bite out of sanctions.

That proved to be a fatal miscalculation. Whereas in the past the loss of Western markets – particularly for Russian energy exports, the lifeblood of Moscow’s war machine – would have dealt a fatal blow to the Russian economy, that certainly is no longer the case.

Russia has pivoted its economy away from Western European markets toward those of its BRICS partners in Asia, most notably China and India, which have steadfastly ignored U.S. threats and welcomed sanctioned Russian goods to their vast and rapidly growing economies. Last year Russian energy export earnings hit an all-time high.

An even greater miscalculation by the Biden administration and its allies was ignoring how sanctions would boomerang back on their own economies, opening a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences.

The most obvious of those consequences is the resurrection of inflation, which had been long buried for more than four decades. Sanctions were the trigger for its dramatic revival.

When you sanction shipments from the world’s largest exporter of energy and grain, there are consequences for the prices of substitute supply. Soaring food and energy prices pushed inflation to levels not seen since the OPEC oil shocks. That in turn has forced a crippling rise in interest rates, as central banks such as the Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of Canada were reluctantly forced to respond by raising their target interest rates from near zero to the 5-per-cent range.

And those central bank rate hikes in turn led to the largest correction in the supposedly staid but safe government bond market since before the U.S. Civil War (1860 in the case of the benchmark 10-year Treasuries).

While the North American economy has weathered the storm (apart from the collapse of a few regional banks in the U.S.), the European Union hasn’t been so lucky. Skyrocketing energy costs and soaring interest rates have thrown the entire EU economy into recession, most notably in Germany, and have done the same in Britain. Meanwhile, the Russian economy, after experiencing a very modest decline during the first year of sanctions, has hit a new peak in GDP.

As disheartening as the short-term results have been, the longer-term consequences of sanctions could be even more worrisome.

Historically, trade restrictions have been the normal realm of economic warfare, but today’s sanctions have spread like some terrible contagion to capital and currency markets as well. And just as in trade, there have been boomerang effects.

Sanctioning the ruble and confiscating a third of the Russian central bank’s foreign reserves was supposed to cripple the Russian economy. Instead, it has already cost the U.S. dollar its five-decade status as the petrocurrency of the world and may soon cost it even more: its once unrivalled position as the sole reserve currency in the world during pretty much the entire postwar period.

Similarly, the ultimate consequence of Western firms abandoning their operations in Russia or refusing to sell their goods or services in the Russian market may ultimately fall on those same Western firms.

Instead of forcing Russian consumers (and perhaps soon Chinese consumers as well) to go without Western goods, sanctions have created a vacuum in those markets that is quickly being filled by the growth of indigenous companies. These companies do not only replace Western firms in their own markets, as Russia has already done in aerospace, but in time may come to compete with them in third markets, particularly in BRICS countries.

Ditto for the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions aimed at preventing China from accessing state-of-the-art semi-conductor technology. There can be no greater incentive for the growth and development of China’s chip industry than U.S. attempts to thwart its access to leading-edge technology. Just check out Huawei’s new 5G phone – a technology it wasn’t supposed to possess.

Having spurred the development of alternative, homegrown industries in BRICS countries, have the U.S. and its NATO partners incented the development of new commercial competitors among its geopolitical rivals?

But perhaps the biggest casualty of sanctions is the global trading order that our governments repeatedly assured us was the basis of our collective prosperity. While no fewer than 11 (and likely more still to come) rounds of sanctions have failed to shred the Russian economy as promised, they have managed to shred that very global trading order that we supposedly all cherished.

The exclusion of Russian and, increasingly, Chinese products from Western markets, as well as the ban imposed on investment in and from those countries, undermines a system predicated on the free flow of goods, capital and technology. And that fundamentally changes the way our economies will operate.

Instead of fostering the highly specialized division of labour that globalization compels, sanctions encourage economies to look inward to meet the needs of their domestic markets. Adapting to a world of sanctions requires a local economy to become a jack of all trades, as opposed to specializing in the production of whatever its natural comparative advantage dictates. And that transformation is happening not only in the economies that are being sanctioned but in the economies of sanctioning countries themselves.

For countries that lack the resources to be self-sufficient (and most do), friendshoring provides the new chart book for securing foreign supply among the many obstacles that now stand in the way of global trade. Friendshoring essentially means trading with your political allies instead of with your geopolitical rivals.

“Decoupling” or “derisking” is another way of putting it – and its goal is nothing short of turning the very dynamic of international trade (comparative advantage) on its head.

As any economics undergraduate student will realize, if Ricardo’s dictum of comparative advantage makes everyone better off, then sanctions do the exact opposite. But the logic of economics doesn’t seem to matter any more. All that matters is security of supply in a world that seems inexorably heading toward global war – if not military, certainly economic.

Friendshoring may make supply chains a lot more secure in a world where economic warfare has become the norm. But the only problem with friendshoring is that most of America’s friends are high-wage economies much like its own. They are the last places global corporate titans such as Apple want to be making their products.

If Apple produced its iPhone in its home state of California, where the minimum wage is US$15.50 an hour, instead of in China, where its principal supplier, Foxconn, pays US$1.50 an hour, you probably couldn’t afford to buy it. And that doesn’t hold true just for Apple. That holds true for virtually everything imported from China.

The realignment of global supply chains along a geopolitical axis, as opposed to cost considerations, is going to make the world a lot more expensive for generations of Western consumers who have grown accustomed to reaping the price benefits of cheap overseas labour.

No longer will trade be driven by economic imperatives. Instead, international trade will be driven by geopolitical considerations. Suddenly, the foreign policies of a country’s government, not the cost competitiveness of its industries, will determine trade flows. At least from an economist’s perspective, the emerging new world order will be a lot less efficient than the old order it is rapidly replacing.

Insofar as the lead imposer of sanctions, the United States, is concerned, it hasn’t really mattered whether there was a Democratic or Republican administration in office; sanctions have been on an upward trajectory no matter which party was in the White House. Sanctions imposed by the Office of Foreign Asset Control soared from 540 a year under the Obama administration to 975 a year under Donald Trump and 1,175 under Mr. Biden.

Sanctions are no longer the exception. Instead, they have become part of the new normal. And so have their consequences.

[ad_2]

Source link