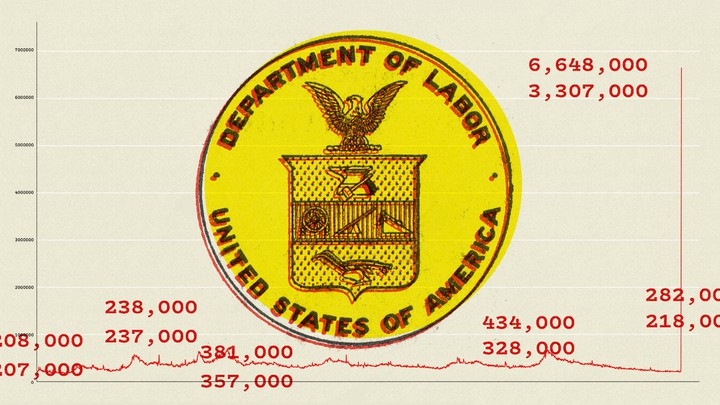

For the second straight week, the U.S. workforce set a dismal unemployment record. On Thursday morning, the Labor Department reported that 6.6 million people filed new claims for unemployment benefits last week. That figure is twice as high as the previous record of 3.3 million, set just seven days ago.

This brings the two-week total of initial claims to nearly 10 million. That’s 10 million Americans who have lost their jobs—and, in many cases, their health insurance—in the spiraling chaos of a public-health crisis. Ten million Americans who have been thrust into unemployment-insurance programs, with their company on pause, their start-up ruined, or their business closed, and no clear timeline for reopening. Ten million Americans, many effectively quarantined by local law, simultaneously dealing with sudden confinement and sudden joblessness, separated from their daily habits and prohibited from leaving their apartment to commiserate with colleagues, or seek comfort in the arms of family.

Derek Thompson: The four rules of pandemic economics

In short, the U.S. is accelerating toward an economic and human disaster unlike anything recorded in American history.

During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, the economy suffered a net loss of approximately 9 million jobs. The pandemic recession has seen nearly 10 million unemployment claims in just two weeks. Some states are convulsing at a rate of one Great Recession every few days. After the financial crash, Hawaii’s unemployment rate peaked at 7.3 percent. In the past week, exactly 7.3 percent of Hawaiian workers filed for unemployment benefits

As mind-numbingly awful as these official figures are, they likely understate the severity of the joblessness crisis. Some unemployed people don’t know to file for jobless benefits, and others wait several weeks before collecting insurance. There are widespread reports that people have been stymied by crashing websites and hour-long waits on the phone with state offices, which have been slammed by the historic surge in claims. Our economic data, like our public-health data, are shrouded in uncertainty: In many cases, we simply don’t know whether our more dire statistics are measuring reality or we have simply maxed out our capacity to measure in the first place.

Read: Everyone thinks they’re right about masks

In the early innings of the crisis, it was obvious that the forced closure of city streets would be an apocalypse-level event for restaurants, the travel industry, concerts, amusement parks, and any other company in the business of attracting a crowd. But the economic stoppage is now rippling into almost every sector of the economy. When restaurants and stores cannot open, they can’t order new supplies. When farms can’t supply restaurants with food, they can’t afford new equipment. Without new equipment orders, manufacturers have to lay off workers. If you drop a boulder into the middle of a pond, the waves will eventually reach every edge.

The most important question is: What can we do now?

Tragically, the U.S. likely missed its best opportunity to avoid mass layoffs. That would have been to take a page out of Denmark’s playbook and directly pay businesses to meet their payroll obligations and retain their employees. This would have accomplished several important goals. By reducing layoffs, it would have kept workers inside their companies, so that firms would have an easier time ramping up after the crisis passes. By reducing unemployment, it would have kept workers from having to take it on themselves to wait for hours on the phone, or online, to secure jobless benefits. By freezing the economy, it would have reduced anxiety for millions of people who, at this moment, don’t know where their next job is, or when they should realistically think about applying for work.

But with jobless claims surging toward 10 million, we may be too late to pivot toward the northern-European approach.

Instead, the U.S. economic rescue package implicitly encourages layoffs and increases spending on the unemployed. Jobless benefits have been expanded, and many households will receive one-time payments of $1,200 per adult—plus $500 per child.

Strengthening our jobless benefit programs in this way was necessary to keep families from starving, given the inevitability of historic layoffs. But had the U.S. reacted swiftly and creatively to the prospect of a historic sudden-stop recession, this level of layoffs would not have been inevitable. We could have paid workers a living wage to stay with their companies. Instead, companies are firing workers en masse, and we’re scrambling to pay them a living wage anyway.

While it may be too late to reverse the millions of layoffs that have already happened, Congress still has a chance to stem the tide. This can start with building on to the emergency rescue package. The new law provides for more than $300 billion in loans to small- and medium-size companies through the Small Business Administration. These loans are designed to be forgiven if the companies borrowing money don’t fire their workers.

Adam Serwer: We can finally see the real source of Washington gridlock

The government can immediately strengthen this program in two ways—with more marketing and more money. First, the administration should advertise the program, repeatedly, publicly urging companies to use government money to continue to pay their workers. The message should be: You have a patriotic and moral duty to hold on to your workers during this national crisis, and the government has a patriotic and moral duty to pay you to do it.

Second, Congress should return to session immediately to double the loan guarantees to more than $600 billion. That is approximately equal to 11 weeks of payroll for all companies with fewer than 500 employees in the United States.

Instead, we are already in danger of moving in the opposite direction. Instead of rushing a larger small-business bailout through Congress, Senator Mitch McConnell has criticized Democrats who are calling for follow-up legislation.

If Congress does not move quickly, more ghastly history-making awaits us. At the height of the Great Depression, in 1933, approximately 25 percent of Americans were out of work. In the past two weeks, 6 percent of Americans filed for jobless benefits. Today, we are dealing with a light-speed recession. But after two months of this, the word recession might not be sufficient.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

/media/None/Derek_Thompson_grey/original.png)