Investment

The rise and dramatic fall of European investment banks in the US – Financial Times

When HSBC interim chief executive Noel Quinn announced a dramatic overhaul last month to try to restore the bank’s fortunes, he took aim at what has now become a familiar target for European bank bosses — the US market.

HSBC, which was just last year talking about adding 50 more retail branches to its 220-strong US network, is now closing 30 per cent of its branches after admitting the division is lossmaking. Its US trading business is in the line of fire too; Mr Quinn is cutting its assets as measured by risk by 45 per cent, a bigger reduction than HSBC’s businesses elsewhere, after profits from the US markets business fell by more than 20 per cent last year.

The announcement was the latest in a series of humbling withdrawals by European banks from the US market. Last year Deutsche abandoned its quest to be part of Wall Street’s elite by closing its global equities business and cutting thousands of jobs.

UBS cut back much of its US bond trading business after the financial crisis, while Credit Suisse is also a much smaller force in the US, having pared back its investment bank and leaving US private banking in recent years.

These cuts represent a dramatic retreat from the two decades when European banks went on an acquisition spree in the US in a bid to capture part of the world’s most lucrative banking and trading markets.

Through deals such as Deutsche’s 1998 acquisition of Bankers Trust, Credit Suisse’s 2000 takeover of DLJ and HSBC’s 2003 purchase of consumer finance business Household, European banks pumped billions into the pre-crisis US market. Barclays joined the party later with the most prestigious deal of them all, the $1.75bn takeover of Lehman Brothers at the height of the crisis.

Amid the acquisitions, European banks hired some of Wall Street’s top dealmakers, won places on prestigious deals and became big players in areas such as leveraged finance and fixed-income trading.

“From 2002 to 2007 there was tremendous [market] share growth by the Europeans,” says a senior European investment banker of that era. “I don’t believe any of those banks would have got to where they were organically.”

But those heady ambitions now lie in tatters.

For some observers, the swingeing cuts now being made are a recognition that few Europeans have built strong businesses in the US. “We do not see European bank management creating value to their shareholders with US . . . operations and would welcome exit strategies,” says Kian Abouhossein, JPMorgan’s head of European banks analysis.

Yet some of the bankers who were involved in the expansion believe that it was a lack of ambition — not overreaching — that has left the European banks in such a dilemma now.

“It’s very hard to retain the best people in the industry when your goal is to be number six,” says Ken Moelis, one of the most prominent investment bankers in Los Angeles who was hired by UBS and later founded his own boutique investment bank.

European lenders’ first move on the American market was in 1978, when Credit Suisse made what proved to be a trendsetting investment in top tier Wall Street advisory firm First Boston.

The Swiss bank took a controlling stake in its American partner in 1988. By 1998, Credit Suisse looked to have cracked one of the world’s most exclusive clubs, ranking third in US investment banking fees ahead of both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, according to Dealogic.

Meanwhile, European banks were increasingly rankled by competition on their home turf from the likes of Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, who arrived in London in the 1990s and could offer round-the-world services to corporate clients.

Enter Deutsche. In 1998, after years pondering how to crack the US market, the German lender set the record for the largest foreign takeover of an American bank with its $10bn purchase of Bankers Trust. “There wasn’t a hell of a lot of discussion,” recalls a Deutsche management board member of that era. “There was a sense that scale is everything.”

Two years later, Credit Suisse doubled down with its $11.5bn acquisition of leveraged buyout specialist DLJ, and UBS snapped up brokerage Paine Webber for $12bn that same year. HSBC spent $14.8bn on Household in 2003.

Bolstered by their acquisitions, the European investment banks had some of Wall Street’s most famous rainmakers at their disposal. They included Mr Moelis, Blair Effron, his colleague at UBS who set up private equity house Centerview, and Tony James, who also worked at Credit Suisse in that era and is now the number two at private equity group Blackstone.

“I joined in 2001 and to me it was an opportunity,” says Mr Moelis. “UBS had Warburg in Europe, it had just merged with Paine Webber, they really had nothing in the US, they were merging two very suboptimal investment banks . . . I did think I could bring them the US.”

An executive who sat on Deutsche’s management board at the time of the Bankers Trust acquisition says the deal “totally changed the dynamic of the conversation with senior US bankers [Deutsche was trying to hire]. Deutsche Bank had a credible platform overnight.” Deutsche was able to muscle its way into some landmark deals, including a 2012 mandate to advise AIG on its return to the public market.

But even in the period before the financial crisis, which European banks regard as their heyday in the US, their record was patchy. Deutsche was the eighth-biggest earner of investment banking fees in 2002, its $872m far behind the $2.6bn earned by market leader Bank of America. By 2007, Deutsche had fallen to ninth, with $1.6bn of fees versus JPMorgan’s $4.4bn.

Barclays and UBS also remained outside the top five players in most areas of investment banking, leaving Credit Suisse as the only one that really challenged the Americans.

Although their trading operations expanded, the underlying profitability was unclear — especially as some of the profits they booked were linked to mortgage-related trades that later registered large losses. Retail operations also struggled, such as HSBC’s Household business, which it closed to new business a few years after buying it.

“I’m not sure any large British bank and maybe no European bank has ever made money over a couple of credit cycles in the US market,” says Paul Tucker, a former deputy governor of the Bank of England who is now at Harvard University.

A former European bank CEO says banks “went to enormous lengths to disguise” the economics of their US businesses. “They were trying to fool not only the clients but in some cases your own employees.” If employees had known how bad it was, they would have decided it was “better get a job down the road”.

Bob Diamond, chief executive of Barclays when it bought Lehman, stands firm. “They were all real, with the exception of subprime,” he says of the profits that Barclays enjoyed in that period. “And that was pretty much true across the industry.”

Whether the pre-crisis years were a boom or not for European banks in the US, many executives believe that the seeds for their decline were laid in that period.

“European banks had a false dawn,” says one senior investment banker, adding that from 2012 to 2019 their fortunes went down in a “straight vertical line”.

European policymakers say the region’s banks were allowed to take excessive risk. Unlike in Europe, the US has had an absolute cap on leverage since 1981. European banks expanded their balance sheets to 60 times their common equity in the run-up to the crisis, versus 35 times leverage at their US peers, as they built up far bigger trading exposures.

“(There were) abject failures of supervision. Partly regulatory failures as well,” says one former official.

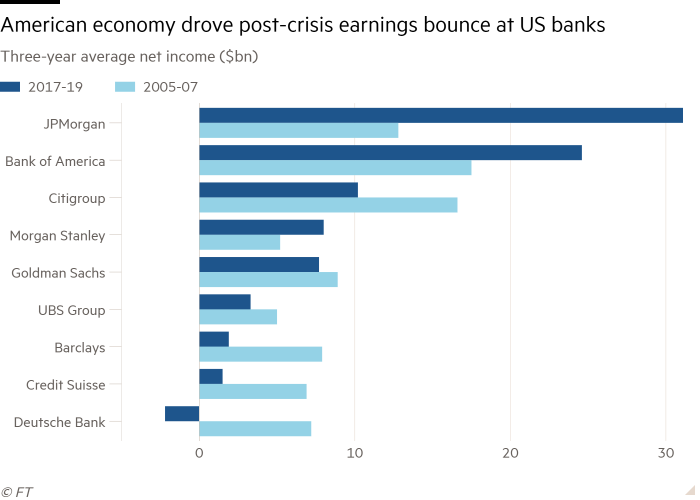

In the decade since the crisis, the relative weakness of the European economy compared with the US has left the continent’s banks at a disadvantage and given their American rivals more resources to expand.

The US industry also benefited from the more proactive approach to bailing out banks in the aftermath of the financial crisis. “The government capital that helped put those guys hack on their feet meant that those competitors came back,” says one Credit Suisse banking executive. “I thought those guys would pay a heavier price for being wrong and have to struggle.”

For the bankers, the biggest reason for the fall in profits in the US has been regulation. They cite everything from the Federal Reserve’s 2008/09 decision to force foreign banks to ringfence and fully capitalise their US operations by 2016, to global capital rules that struck at the fixed income businesses which were the core of Barclays’ and Deutsche’s Wall Street operations.

Frustrated by bureaucracy and centralised management, the cadre of star dealmakers at European banks gradually departed for more lucrative pastures, often setting up their own operations and taking their clients with them.

“I went there to create something great,” says Mr Moelis of his 2007 decision to quit UBS. “I don’t think they wanted to be great. They wanted to be good. Some of the European banks, their mentality was, let’s just get good.”

Christian Meissner, the head of investment banking for Bank of America from 2010 to late 2018, says “none of the European banks have been sufficiently consistent about building a business in the US and, while they’ve been able to attract talent, they’ve rarely been able to keep it over an extended period,” he says.

“They really had nothing to bring to the table but money,” argues the former CEO of a large European bank. “Partly as a consequence, the US bankers had little respect for them and felt super-entitled to rip them off.”

© Andrew Winning/Reuters

He adds that while Goldman “steered by the wind and stars like Polynesian sailors” as it allocated capital into areas of high returns and pulled back when markets turned, European companies were “highly structured” in their planning and not responsive enough to changing conditions.

Nowhere was this more evident than at Deutsche, which last summer finally made the kind of cuts to its investment bank that rivals Barclays and UBS had made more than five years earlier and US banks made earlier still.

Deutsche insiders now privately accept that mistakes were made. The bank rushed to celebrate its early successes after the crisis when it should have been more circumspect. Top management believed changes in the industry — such as new capital requirements and lower fees — would be temporary and the bank paid a catastrophic price, racking up cumulative group-wide pre-tax losses of almost €7bn in the five years to the end of 2019.

HSBC interim chief executive Noel Quinn said last week his bank could get “acceptable returns” over the medium term from a transformed US operation, which would be an important part of HSBC’s global business. Deutsche made similar arguments last summer when it announced cuts.

Still, most outsiders are downbeat about the Europeans’ prospects, arguing that technology has made scale more important than ever in investment banking, while negative interest rates in Europe leave the continent’s banks with a weaker financial base to build from.

Continental moves

$10bn

Value of Deutsche Bank’s 1998 deal to buy Bankers Trust, the largest foreign takeover of a US company at the time

$11.5bn

Price Credit Suisse paid for leveraged buyout specialist DLJ in 2000. It was also first into the US with the 1978 deal to First Boston

$12bn

Value of UBS’ deal to acquire brokerage Paine Webber in the same year. Ken Moelis, once head of its investment bank, left UBS in 2007

“You have this bifurcation,” says Mr Moelis. “[If you want] money and capital and size, go to JPMorgan, Citi etc. If you want scale, they [European banks] are not there. If you want nimble and smart you’re going to go to us [boutiques]. I think the middle is the killing field.”

The future of European banks on Wall Street is “linked to a bigger question”, Mr Tucker says. “In the new geopolitics, can you be a serious continent without some of your own global universal banks?”

The British view, he says, has been that ownership of the banking sector is not an issue “so long as finance is open, sound and honest, and the domestic economy well served”. But he adds: “The Paris view has been no, we need big international firms who somehow are aligned in a loose but meaningful way with our national or continental interest.”

A European investment bank boss puts it more bluntly. “Investment banks are the ultimate bastions of capitalism,” he says. “Europe is not a bastion of capitalism. There’s political pressure against the forces of capitalism . . . It’s just harder to succeed.”

An American firm’s investment banking head singles out Barclays as “the only one that has a shot” but says it is “as much of an American firm as they are a European one” thanks to the Lehman acquisition.

One senior European investment banker is even more dismissive: “There was a brief period in 2000-07 when it was possible to compete as a global investment bank with headquarters outside the US. We’re back to investment banking being an exclusively US industry.”

Investment

Everton search for investment to complete 777 deal – BBC.com

-

2 hours ago

Everton are searching for third-party investment in order to push through a protracted takeover by 777 Partners.

The Miami-based firm agreed a deal to buy the Toffees from majority owner Farhad Moshiri in September, but are yet to gain approval from the Premier League.

On Monday, Bloomberg reported the club’s main financial adviser Deloitte has been seeking fresh funding from sports-focused investors and lenders to get 777’s deal over the line.

BBC Sport has been told this is “standard practice contingency planning” and the process may identify other potential lenders to 777.

Sources close to British-Iranian businessman Moshiri have told BBC Sport they remain “working on completing the deal with 777”.

It is understood there are no other parties waiting in the wings to takeover should the takeover fall through and the focus is fully on 777.

The Americans have so far loaned £180m to Everton for day-to-day operational costs, which will be turned into equity once the deal is completed, but repaying money owed to MSP Sports Capital, whose deal collapsed in August, remains a stumbling block.

777 says it can stump up the £158m that is owed to MSP Sports Capital and once that is settled, it is felt the deal should be completed soon after.

Related Topics

Investment

Warren Buffett Predicts 'Bad Ending' for Bitcoin — Is It a Doomed Investment? – Yahoo Finance

Currently sitting in sixth on Forbes’ Real-Time Billionaires List, Berkshire Hathaway co-founder, chairman and CEO Warren Buffett is a first-rate example of an investor who stuck to his core financial beliefs early in life to become not only a success but a once-in-a-lifetime inspiration to those who followed in his footsteps.

One of the most trusted investors for decades, the 93-year-old Buffett isn’t shy to pontificate on his investment philosophy, which is centered around value investing, buying stocks at less than their intrinsic value and holding them for the long term.

Read Next: Warren Buffett: 6 Best Pieces of Money Advice for the Middle Class

Find Out: 5 Genius Things All Wealthy People Do With Their Money

He’s also quite vocal on investments he deems worthless. And one of those is Bitcoin.

Buffett’s Take on Bitcoin

Over the past decade, it’s been clear that the crypto craze isn’t something Buffett wants any part of. He described Bitcoin as “probably rat poison squared” back in 2018.

“In terms of cryptocurrencies, generally, I can say with almost certainty that they will come to a bad ending,” Buffett said in 2018. And his stance hasn’t wavered since. According to Benzinga, Buffett believes that cryptocurrencies aren’t a viable or valuable investment.

“Now if you told me you own all of the Bitcoin in the world and you offered it to me for $25, I wouldn’t take it because what would I do with it? I’d have to sell it back to you one way or another. It isn’t going to do anything,” Buffett said at the Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meeting in 2022.

Although the Oracle of Omaha has his misgivings about the unpredictable investment, does that mean crypto is doomed as an investment? Not necessarily.

For You: 10 Valuable Stocks That Could Be the Next Apple or Amazon

Is Buffett Wrong About Bitcoin?

Bitcoin bulls argue that while it’s not government-issued, cryptocurrency is as fungible, divisible, secure and portable as fiat currency and gold. Because they occupy a digital space, cryptocurrencies are decentralized, scarce and durable. They can last as long as they can be stored.

Crypto boosters continue to predict massive growth in the coin’s value. Earlier this year, SkyBridge Capital founder and former White House director of communications Anthony Scaramucci told reporters that Bitcoin could exceed $170,000 by mid-2025, and Ark Invest CEO Cathie Wood predicts Bitcoin will hit $1.48 million by 2030, according to Fortune.

“They really don’t understand the concept and the whole history of money,” Scaramucci said of crypto critics like Buffett on a recent episode of Jason Raznick’s “The Raz Report.” Because we place a value on “traditional” currency, it is essentially worthless compared with the transparent and trustworthy digital Bitcoin, Scaramucci said.

Currently trading around the $66,000 mark, Bitcoin is up nearly 50% in 2024. This means it’s massively outperforming most indexes this year, including the S&P 500, which is up about 6% in 2024.

Although Berkshire Hathaway has invested heavily in Bitcoin-related Brazilian fintech company Nu Holdings, which has its own cryptocurrency called Nucoin, it’s possible Buffett will never come around fully to crypto, despite its recent surge in value. It’s contrary to the reliable investment strategy that has served him very well for decades.

“The urge to participate in something where it looks like easy money is a human instinct which has been unleashed,” Buffett said. “People love the idea of getting rich quick, and I don’t blame them … It’s so human, and once unleashed you can’t put it back in the bottle.”

More From GOBankingRates

This article originally appeared on GOBankingRates.com: Warren Buffett Predicts ‘Bad Ending’ for Bitcoin — Is It a Doomed Investment?

Investment

Ping An Profit Falls as Market Declines Hurt Investment Returns – BNN Bloomberg

(Bloomberg) — Ping An Insurance (Group) Co.’s profit dropped 4.3% in the first quarter as stock-market declines and falling bond yields eroded investment returns.

Net income fell to 36.7 billion yuan ($5 billion) in the three months ended March 31, from 38.4 billion yuan a year earlier, the Shenzhen-based company said in a filing to the Hong Kong stock exchange Tuesday.

Operating profit, which strips out one-time items and short-term investment volatility, fell 3%.

China’s stock market rout at the start of the year and lower bond yields have weighed on insurers’ investment returns. They hurt profit even as more customers seek to buy savings products. Co-Chief Executive Officer Michael Guo said last month that profitability will recover after a 23% drop in net income last year.

“China’s macroeconomy gradually recovered in the first three months of 2024, but there were still challenges,” the company said in a statement, citing weak domestic demand. “In response to volatile capital markets and declining treasury yields, Ping An continued to pursue long-term returns through cycles via value investing.”

Read More: Ping An Trust Wins First Court Ruling Over Delayed Trust Product

Net investment yield of insurance funds dropped to 3%, the statement said, down from 3.1% a year earlier. Real estate investments fell to 4.2% of the 4.9 trillion yuan portfolio, from 4.6% the year earlier.

The CSI 300 Index slumped as much 7.3% this year through the start of February, before government intervention fueled a rally.

New business value, which gauges the profitability of new life policies sold, rose 21% in the first quarter. That followed a 36% jump last year as the company’s efforts to improve the productivity of life agents started to bear fruit. NBV per agent jumped 56% from a year earlier, the statement said.

Ping An shares rose 3% to HK$33.00 in Hong Kong trading on Tuesday, trimming the year’s loss to 6.7%.

(Updates with company comment in fifth paragraph, more details afterwards)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

-

Health22 hours ago

Health22 hours agoSee how chicken farmers are trying to stop the spread of bird flu – Fox 46 Charlotte

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoOwn a cottage or investment property? Here's how to navigate the new capital gains tax changes – The Globe and Mail

-

Science20 hours ago

Science20 hours agoOsoyoos commuters invited to celebrate Earth Day with the Leg Day challenge – Oliver/Osoyoos News – Castanet.net

-

News24 hours ago

‘A real letdown’: Disabled B.C. man reacts to federal disability benefit – Global News

-

News21 hours ago

Freeland defends budget measures, as premiers push back on federal involvement – CBC News

-

Politics20 hours ago

Politics20 hours agoHaberman on why David Pecker testifying is ‘fundamentally different’ – CNN

-

Economy21 hours ago

The Fed's Forecasting Method Looks Increasingly Outdated as Bernanke Pitches an Alternative – Bloomberg

-

Business24 hours ago

Ottawa puts up $50M in federal budget to hedge against job-stealing AI – CP24