Science

Two satellites just avoided a head-on smash. How close did they come to disaster? – The Conversation AU

It appears we have missed another close call between two satellites – but how close did we really come to a catastrophic event in space?

It all began with a series of tweets from LeoLabs, a company that uses radar to track satellites and debris in space. It predicted that two obsolete satellites orbiting Earth had a 1 in 100 chance of an almost direct head-on collision at 9:39am AEST on 30 January, with potentially devastating consequences.

LeoLabs estimated that the satellites could pass within 15-30m of one another. Neither satellite could be controlled or moved. All we could do was watch whatever unfolded above us.

Collisions in space can be disastrous and can send high-speed debris in all directions. This endangers other satellites, future launches, and especially crewed space missions.

As a point of reference, NASA often moves the International Space Station when the risk of collision is just 1 in 100,000. Last year the European Space Agency moved one of its satellites when the likelihood of collision with a SpaceX satellite was estimated at 1 in 50,000. However, this increased to 1 in 1,000 when the US Air Force, which maintains perhaps the most comprehensive catalogue of satellites, provided more detailed information.

Read more:

You, me and debris: Australia should help clear ‘space junk’

Following LeoLabs’ warning, other organisations such as the Aerospace Corporation began to provide similarly worrying predictions. In contrast, calculations based on publicly available data were far more optimistic. Neither the US Air Force nor NASA issued any warning.

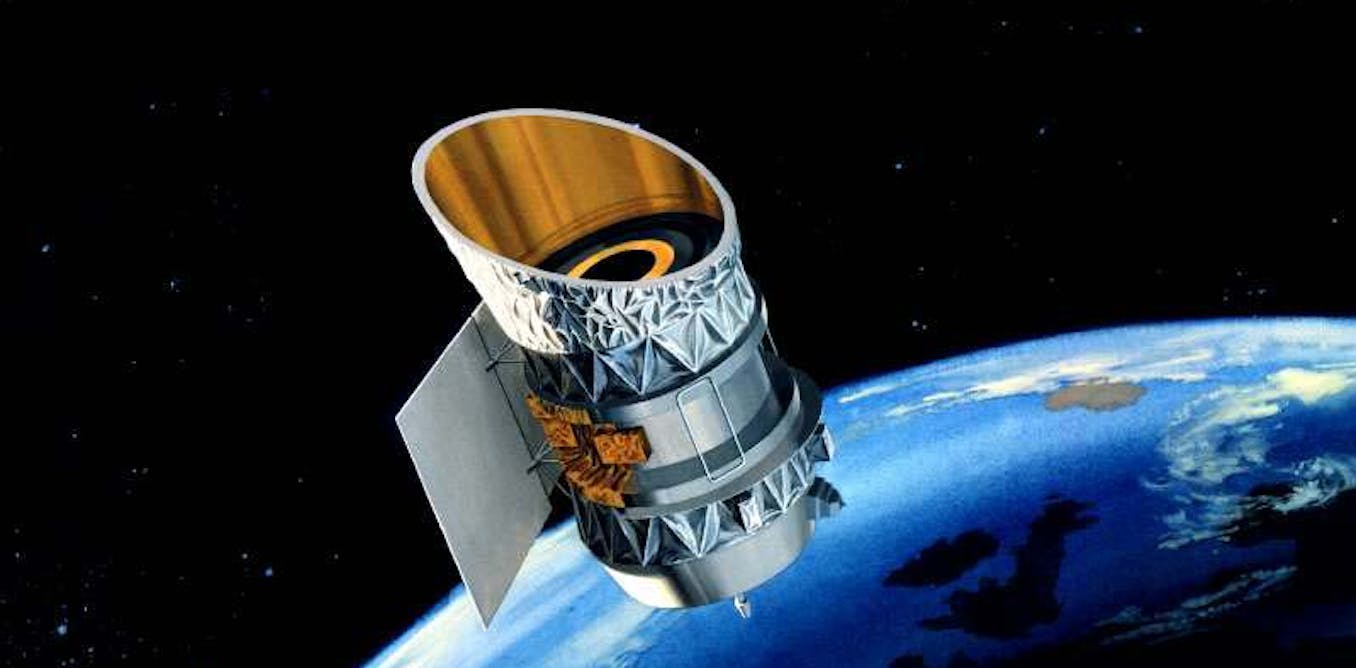

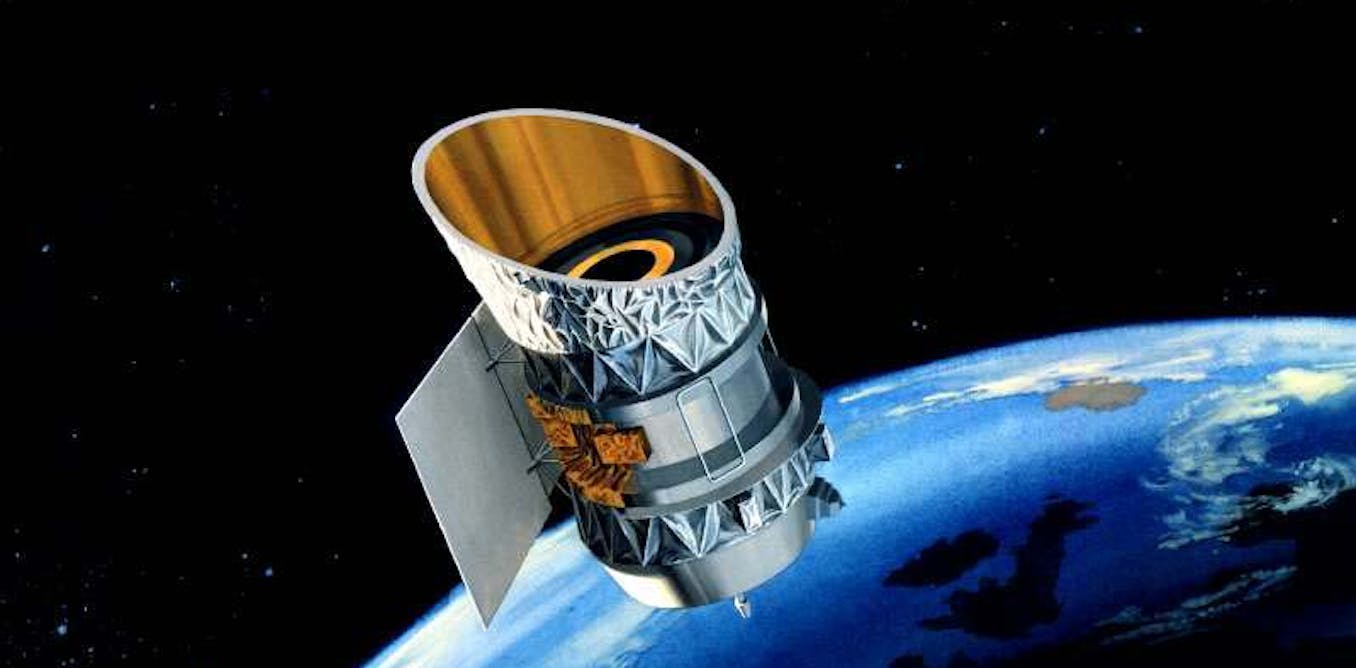

This was notable, as the United States had a role in the launch of both satellites involved in the near-miss. The first is the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), a large space telescope weighing around a tonne and launched in 1983. It successfully completed its mission later that year and has floated dormant ever since.

The second satellite has a slightly more intriguing story. Known as GGSE-4, it is a formerly secret government satellite launched in 1967. It was part of a much larger project to capture radar emissions from the Soviet Union. This particular satellite also contained an experiment to explore ways to stabilise satellites using gravity.

Weighing in at 83kg, it is much smaller than IRAS, but it has a very unusual and unfortunate shape. It has an 18m protruding arm with a weight on the end, thus making it a much larger target.

Almost 24 hours later, LeoLabs tweeted again. It downgraded the chance of a collision to 1 in 1,000, and revised the predicted passing distance between the satellites to 13-87m. Although still closer than usual, this was a decidedly smaller risk. But less than 15 hours after that, the company tweeted yet again, raising the probability of collision back to 1 in 100, and then to a very alarming 1 in 20 after learning about the shape of GGSE-4.

The good news is that the two satellites appear to have missed one another. Although there were a handful of eyewitness accounts of the IRAS satellite appearing to pass unharmed through the predicted point of impact, it can still take a few hours for scientists to confirm that a collision did not take place. LeoLabs has since confirmed it has not detected any new space debris.

But why did the predictions change so dramatically and so often? What happened?

Tricky situation

The real problem is that we don’t really know precisely where these satellites are. That requires us to be extremely conservative, especially given the cost and importance of most active satellites, and the dramatic consequences of high-speed collisions.

The tracking of objects in space is often called Space Situational Awareness, and it is a very difficult task. One of the best methods is radar, which is expensive to build and operate. Visual observation with telescopes is much cheaper but comes with other complications, such as weather and lots of moving parts that can break down.

Another difficulty is that our models for predicting satellites’ orbits don’t work well in lower orbits, where drag from Earth’s atmosphere can become a factor.

There is yet another problem. Whereas it is in the best interest of commercial satellites for everyone to know exactly where they are, this is not the case for military and spy satellites. Defence organisations do not share the full list of objects they are tracking.

This potential collision involved an ancient spy satellite from 1967. It is at least one that we can see. Given the difficulty of just tracking the satellites that we know about, how will we avoid satellites that are trying their hardest not to be seen?

Read more:

Trash or treasure? A lot of space debris is junk, but some is precious heritage

In fact, much research has gone into building stealth satellites that are invisible from Earth. Even commercial industry is considering making satellites that are harder to see, partly in response to astronomers’ own concerns about objects blotting out their view of the heavens. SpaceX is considering building “dark satellites” the reflect less light into telescopes on Earth, which will only make them harder to track.

What should we do?

The solution starts with developing better ways to track satellites and space debris. Removing the junk is an important next step, but we can only do that if we know exactly where it is.

Western Sydney University is developing biology-inspired cameras that can see satellites during the day, allowing them to work when other telescopes cannot. These sensors can also see satellites when they move in front of bright objects like the Moon.

There is also no clear international space law or policy, but a strong need for one. Unfortunately, such laws will be impossible to enforce if we cannot do a better job of figuring out what is happening in orbit around our planet.

Science

Voyager 1 transmitting data again after Nasa remotely fixes 46-year-old probe – The Guardian

Earth’s most distant spacecraft, Voyager 1, has started communicating properly again with Nasa after engineers worked for months to remotely fix the 46-year-old probe.

Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which makes and operates the agency’s robotic spacecraft, said in December that the probe – more than 15bn miles (24bn kilometres) away – was sending gibberish code back to Earth.

In an update released on Monday, JPL announced the mission team had managed “after some inventive sleuthing” to receive usable data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems. “The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again,” JPL said. Despite the fault, Voyager 1 had operated normally throughout, it added.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was designed with the primary goal of conducting close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn in a five-year mission. However, its journey continued and the spacecraft is now approaching a half-century in operation.

Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, making it the first human-made object to venture out of the solar system. It is currently travelling at 37,800mph (60,821km/h).

The recent problem was related to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, which are responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it is sent to Earth. Unable to repair a broken chip, the JPL team decided to move the corrupted code elsewhere, a tricky job considering the old technology.

The computers on Voyager 1 and its sister probe, Voyager 2, have less than 70 kilobytes of memory in total – the equivalent of a low-resolution computer image. They use old-fashioned digital tape to record data.

The fix was transmitted from Earth on 18 April but it took two days to assess if it had been successful as a radio signal takes about 22 and a half hours to reach Voyager 1 and another 22 and a half hours for a response to come back to Earth. “When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on 20 April, they saw that the modification worked,” JPL said.

Alongside its announcement, JPL posted a photo of members of the Voyager flight team cheering and clapping in a conference room after receiving usable data again, with laptops, notebooks and doughnuts on the table in front of them.

The Retired Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who flew two space shuttle missions and acted as commander of the International Space Station, compared the JPL mission to long-distance maintenance on a vintage car.

“Imagine a computer chip fails in your 1977 vehicle. Now imagine it’s in interstellar space, 15bn miles away,” Hadfield wrote on X. “Nasa’s Voyager probe just got fixed by this team of brilliant software mechanics.

Voyager 1 and 2 have made numerous scientific discoveries, including taking detailed recordings of Saturn and revealing that Jupiter also has rings, as well as active volcanism on one of its moons, Io. The probes later discovered 23 new moons around the outer planets.

As their trajectory takes them so far from the sun, the Voyager probes are unable to use solar panels, instead converting the heat produced from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity to power the spacecraft’s systems.

Nasa hopes to continue to collect data from the two Voyager spacecraft for several more years but engineers expect the probes will be too far out of range to communicate in about a decade, depending on how much power they can generate. Voyager 2 is slightly behind its twin and is moving slightly slower.

In roughly 40,000 years, the probes will pass relatively close, in astronomical terms, to two stars. Voyager 1 will come within 1.7 light years of a star in the constellation Ursa Minor, while Voyager 2 will come within a similar distance of a star called Ross 248 in the constellation of Andromeda.

Science

iN PHOTOS: Nature lovers celebrate flora, fauna for Earth Day in Kamloops, Okanagan | iNFOnews | Thompson-Okanagan's News Source – iNFOnews

Photographers are sharing their favourite photos of flora and fauna captured in Kamloops and the Okanagan in celebration of Earth Day.

First started in the United States in the 70s, the special day on April 22 continues to be acknowledged around the globe. It’s a day to celebrate the planet and a reminder of the need for environmental conservation and sustainability, according to EarthDay.org.

These stunning nature photos show life in ponds and forests, in skies and on mountains, capturing the beauty and wonder of our local natural environments.

Area photographers shared some of their favourite finds and artistic captures. From frogs to flowers, the great outdoors is teeming with life.

If you have nature photos you want to share, send them to news@infonews.ca.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Shannon Ainslie or call 250-819-6089 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won’t censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.

Science

An extra moon may be orbiting Earth — and scientists think they know exactly where it came from – Livescience.com

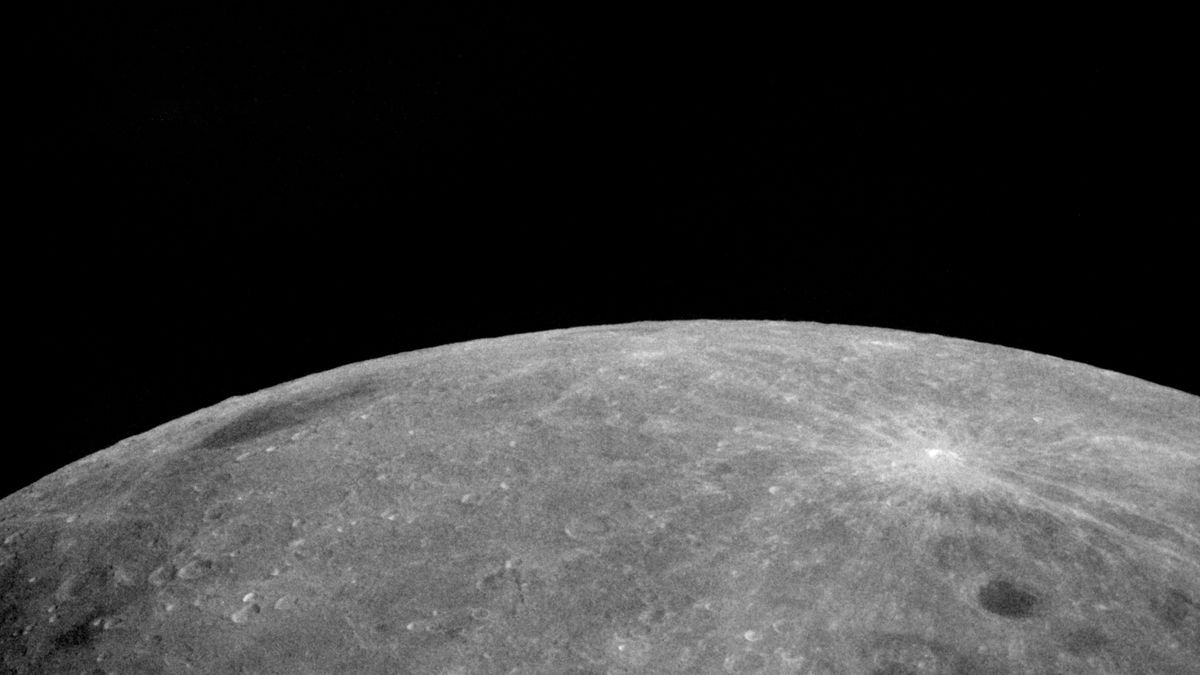

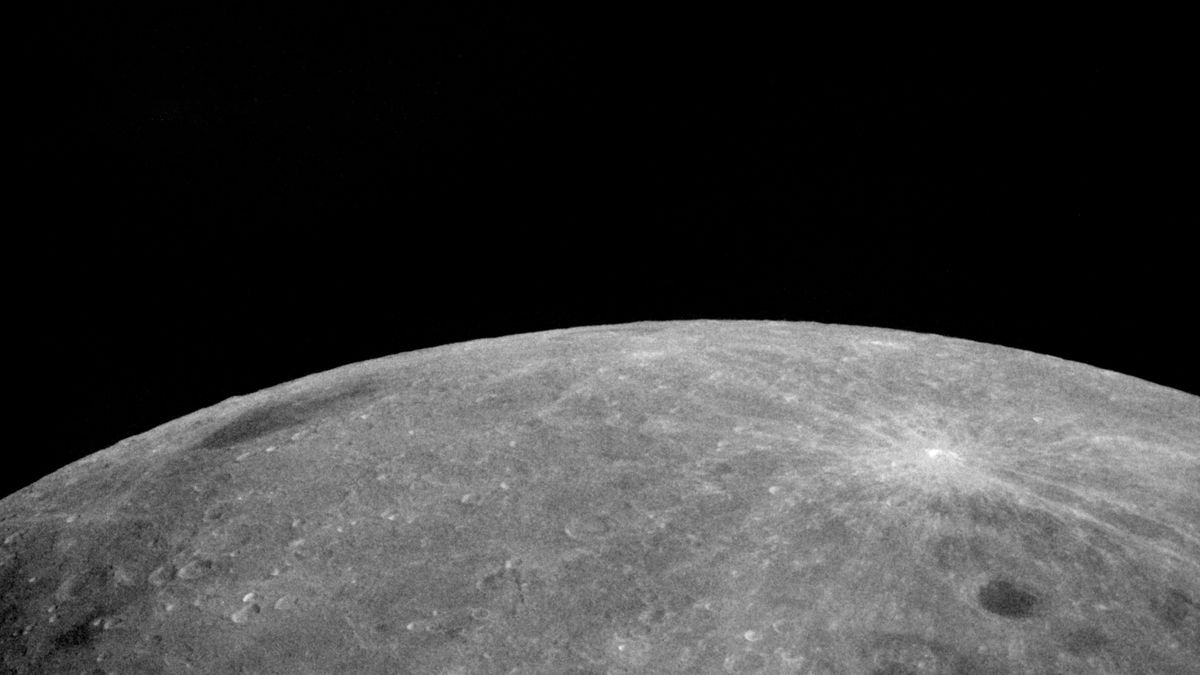

A fast-spinning asteroid that orbits in time with Earth may be a wayward chunk of the moon. Now, scientists think they know exactly which lunar crater it came from.

A new study, published April 19 in the journal Nature Astronomy, finds that the near-Earth asteroid 469219 Kamo’oalewa may have been flung into space when a mile-wide (1.6 kilometers) space rock hit the moon, creating the Giordano Bruno crater.

Kamo’oalewa’s light reflectance matches that of weathered lunar rock, and its size, age and spin all match up with the 13.6-mile-wide (22 km) crater, which sits on the far side of the moon, the study researchers reported.

China plans to launch a sample-return mission to the asteroid in 2025. Called Tianwen-2, the mission will return pieces of Kamo’oalewa about 2.5 years later, according to Live Science’s sister site Space.com.

“The possibility of a lunar-derived origin adds unexpected intrigue to the [Tianwen-2] mission and presents additional technical challenges for the sample return,” Bin Cheng, a planetary scientist at Tsinghua University and a co-author of the new study, told Science.

Related: How many moons does Earth have?

Kamo’oalewa was discovered in 2016 by researchers at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. It has a diameter of about 100 to 200 feet (approximately 30 to 60 meters, or about the size of a large Ferris wheel) and spins at a rapid clip of one rotation every 28 minutes. The asteroid orbits the sun in a similar path to Earth, sometimes approaching within 10 million miles (16 million km).

window.sliceComponents = window.sliceComponents || ;

externalsScriptLoaded.then(() => {

window.reliablePageLoad.then(() => {

var componentContainer = document.querySelector(“#slice-container-newsletterForm-articleInbodyContent-UG4KJ7zrhxAytcHZQxVzXK”);

if (componentContainer)

var data = “layout”:”inbodyContent”,”header”:”Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now”,”tagline”:”Get the worldu2019s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.”,”formFooterText”:”By submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.”,”successMessage”:”body”:”Thank you for signing up. You will receive a confirmation email shortly.”,”failureMessage”:”There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.”,”method”:”POST”,”inputs”:[“type”:”hidden”,”name”:”NAME”,”type”:”email”,”name”:”MAIL”,”placeholder”:”Your Email Address”,”required”:true,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”NEWSLETTER_CODE”,”value”:”XLS-D”,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”LANG”,”value”:”EN”,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”SOURCE”,”value”:”60″,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”COUNTRY”,”type”:”checkbox”,”name”:”CONTACT_OTHER_BRANDS”,”label”:”text”:”Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands”,”type”:”checkbox”,”name”:”CONTACT_PARTNERS”,”label”:”text”:”Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors”,”type”:”submit”,”value”:”Sign me up”,”required”:true],”endpoint”:”https://newsletter-subscribe.futureplc.com/v2/submission/submit”,”analytics”:[“analyticsType”:”widgetViewed”],”ariaLabels”:;

var triggerHydrate = function()

window.sliceComponents.newsletterForm.hydrate(data, componentContainer);

if (window.lazyObserveElement)

window.lazyObserveElement(componentContainer, triggerHydrate);

else

triggerHydrate();

}).catch(err => console.log(‘Hydration Script has failed for newsletterForm-articleInbodyContent-UG4KJ7zrhxAytcHZQxVzXK Slice’, err));

}).catch(err => console.log(‘Externals script failed to load’, err));

Follow-up studies suggested that the light spectra reflected by Kamo’oalewa was very similar to the spectra reflected by samples brought back to Earth by lunar missions, as well as to meteorites known to come from the moon.

Cheng and his colleagues first calculated what size object and what speed of impact would be necessary to eject a fragment like Kamo’oalewa from the lunar surface, as well as what size crater would be left behind. They figured out that the asteroid could have resulted from a 45-degree impact at about 420,000 mph (18 kilometers per second) and would have left a 6-to-12-mile-wide (10 to 20 km) crater.

There are tens of thousands of craters that size on the moon, but most are ancient, the researchers wrote in their paper. Near-Earth asteroids usually last only about 10 million years, or at most up to 100 million years before they crash into the sun or a planet or get flung out of the solar system entirely. By looking at young craters, the team narrowed down the contenders to a few dozen options.

The researchers focused on Giordano Bruno, which matched the requirements for both size and age. They found that the impact that formed Giordano Bruno could have created as many as three still-extant Kamo’oalewa-like objects. This makes Giordano Bruno crater the most likely source of the asteroid, the researchers concluded.

“It’s like finding out which tree a fallen leaf on the ground came from in a vast forest,” Cheng wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Confirmation will come after the Tianwen-2 mission brings a piece of Kamo’oalewa back to Earth. Scientists already have a sample of what is believed to be ejecta from Giordano Bruno crater in the Luna 24 sample, a bit of moon rock brought back to Earth in a 1976 NASA mission. By comparing the two, researchers could verify Kamo’oalewa’s origin.

Editor’s note: This article’s headline was updated on April 23 at 10 a.m. ET.

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoSee how chicken farmers are trying to stop the spread of bird flu – Fox 46 Charlotte

-

Science21 hours ago

Science21 hours agoOsoyoos commuters invited to celebrate Earth Day with the Leg Day challenge – Oliver/Osoyoos News – Castanet.net

-

Politics21 hours ago

Politics21 hours agoHaberman on why David Pecker testifying is ‘fundamentally different’ – CNN

-

News22 hours ago

Freeland defends budget measures, as premiers push back on federal involvement – CBC News

-

Economy22 hours ago

The Fed's Forecasting Method Looks Increasingly Outdated as Bernanke Pitches an Alternative – Bloomberg

-

Health20 hours ago

Health20 hours agoIt's possible to rely on plant proteins without sacrificing training gains, new studies say – The Globe and Mail

-

Business21 hours ago

Gildan replacing five directors ahead of AGM, will back two Browning West nominees – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Tech20 hours ago

Tech20 hours agoMeta Expands VR Operating System to Third-Party Hardware Makers – MacRumors