Art

Victoria art centre offers free therapeutic art sessions – Goldstream News Gazette – Goldstream News Gazette

The Bateman Foundation hopes to harness the healing power of creativity with a series of free therapeutic art sessions.

Materials are provided for the free drop-in sessions, and an on-site art therapist will be available for assistance or mental wellness insight.

“It’s learning about art and nature and using those as tools for wellness,” says Lauren Ball, spokesperson for the Bateman Foundation. “We (wanted) to help people to feel a bit more powerful in their daily lives.”

In the summer of 2020 the foundation launched the Wellness Project, adapting its annual Nature Sketch program for the pandemic and providing it free of charge to small groups in the community.

The new drop-in therapeutic art sessions are an extension of that program, says Bell, and a direct response to the effects of the ongoing pandemic.

READ ALSO: Nature Sketch program returns in Victoria with COVID-19 safety protocols

“Knowing that anxiety and depression are on the rise on this mass scale because of social isolation, we wanted to help in some way,” she said.

“It’s not about being a really great artist, it’s not necessarily about the final result of what you create, it’s about tapping into the creative potential and creative energy that exists within all of us, and using that to find some sense of joy, some sense of peace.”

Art therapist Kaitlin McManus will be on site to help participants who want to discover meaning in their artwork while they are creating.

All ages and experience level are welcome. Four people can participate simultaneously for 30 minutes each, unless there is no one waiting to join, in which case artists can stay longer.

Sessions run twice a week at the Bateman Gallery at 300-470 Belleville St. on Tuesday evenings from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. and on Thursdays from 8:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m. Appointments are not necessary.

READ ALSO: Renowned photographer’s work captured at the Bateman Gallery

Do you have something to add to this story, or something else we should report on? Email: nina.grossman@blackpress.ca. Follow us on Instagram.

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

Art

The true story of Japan’s samurai city that chose art over war

|

|

The breakout series Shōgun has renewed interest in the clashing swords and political maneuvering of Japan’s feudal era – and the city of Kanazawa is an excellent place to learn more.

Long after the end of Japan’s feudal era, there’s still a sense of power and prosperity in Nagamachi, a low-slung neighbourhood at the foot of Kanazawa Castle. Nagamachi’s grand residences, set behind thick earthen walls, were once home to high-ranking samurai retainers of the Maeda family, the powerful clan that ruled the Kaga domain (present-day Ishikawa and Toyama prefectures) from 1583 until the abolition of the shōgunate at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

At the Nomura Residence, which is open to the public, I’m greeted first by an imposing full suit of armour and then pass through rooms filled with delicate craftsmanship towards a tearoom overlooking an ornamental garden. Finally, I end up in front of a display of swords and a letter from a daimyō (feudal lord) thanking his vassal for the gift of an enemy’s head. This juxtaposition of beauty and brutality is a reminder of the samurai’s seemingly paradoxical cultivation of the arts of both war and culture.

The breakout TV series Shōgun has renewed interest in the clashing swords and political manoeuvring of Japan’s turbulent Warring States period (roughly 1467-1615), when rival daimyō fought for control of the country. Bringing to life the political landscape of early 17th-Century Japan, the show reimagines the lead up to the establishment of the Edo period under the Tokugawa shōgunate, founded in 1603 by Ieyasu Tokugawa (inspiration for the fictional Lord Toranaga), which unified Japan and ended more than a century of constant warfare. A visit to Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa Prefecture, reveals the lasting legacy of a surprising tactic that helped to maintain that hard-won peace and stability.

A city of around 465,000 residents on Japan’s west coast, Kanazawa’s well-preserved Edo-period townscapes, like those of Nagamachi and its three geisha districts, have the kind of historical atmosphere and cultural appeal that have garnered many places in Japan the nickname “little Kyoto”. But, says Toshio Ōhi Chōzaemon XI, the 11th-generation head of a local family known for its rustic style of pottery, made without a wheel, “We are not trying [to be] that kind of city”.

He slides open a door to reveal a tearoom in the back of his Ōhi Museum, which, attached to an old samurai residence on the other side of the castle, displays works by each generation of Ōhi potter. He explains that compared to the Imperial Court culture of Kyoto, “We have [more] freedom. We don’t have to follow their tight traditions.” It’s this sensibility, which Ōhi calls the “samurai spirit”, that allows Kanazawa to preserve the beauty of its traditions while reinventing them for modern life.

In the 17th Century, when wealth was measured in koku (the amount of rice a domain produced), the Maeda were second only to the Tokugawa. “They were very powerful [and] had lots of resources [including] weapons,” says Jun Murakami, assistant director of the Kanazawa Utatsuyama Kogei Kobo, a craft school located in a hilly, wooded part of the city.

Murakami explains that the Maeda worried their arsenal would appear threatening to the ruling shōgunate – although the Maeda were by then allied with Tokugawa, he had been an adversary of the first Kaga lord Toshiie Maeda (inspiration for Sugiyama in the Shōgun series) who died in 1599. The Maedas’ solution was to embrace a kind of soft power: they redirected their weapon-making resources to crafts.

“It was like, ‘yes we are powerful, but we are not planning to make war’,” explains Murakami.

The Maeda established a craft-making workshop, Osaikusho, in Kanazawa Castle, inviting master craftspeople from around Japan to teach there and set about turning everyday objects into works of art. The school broke with strictly delineated craft-making tradition by inviting craftspeople of different disciplines to work together, thus moving traditions forward.

While pointing out pieces produced by the school, from a tissue box intricately decorated with metal inlay to gleaming katana swords that Osaikusho craftspeople transformed from lethal instruments to works of art, Murakami explains the Maeda’s lasting impact. If they “didn’t have the mentality of expanding crafts and using those resources to create this school,” he says, “maybe nowadays Kanazawa would not be as famous for its arts and crafts”.

Kanazawa has 22 kinds of traditional arts, including kutani-yaki (pottery), urushi (lacquerware), Kaga yūzen (silk kimono dying) and Kaga zougan (inlay metalwork). It is also the national capital of the production of kinpaku (gold leaf) and the many glittering things made with it, from Buddhist shrines to facial masks. Throughout history, Kanazawa’s promotion of crafts has been guided by a yearning for peace. Soon after World War Two, the Kanazawa College of Art was founded with the philosophy of “contributing to the peace of mankind through the creation of beauty”. In 2009, following a successful application that argued that the city could contribute to “international cooperation and world peace through the promotion of craftwork”, Unesco named Kanazawa Japan’s first City of Crafts and Folk Art.

Today, the contemporary challenges of a shrinking population and shifting culture mean that Kanazawa’s craft heritage is kept alive by a diminishing number of craftspeople. Nevertheless, guided by the dynamic attitude of its past feudal lords, the city is committed to preserving its crafts. In the spirit of the old Osaikusho, Kanazawa established the Kobo craft school in 1989. There, artists on scholarships study ceramics, lacquerware, silk dyeing, metalwork and glasswork. Murakami says that the school wants the students to challenge themselves, both in their art and attitudes. “They have to adapt to keep the tradition going [and meet] the needs of the modern times.”

More like this:

• Why you should visit Japan’s small but mighty ‘little Kyoto’

• The masters of a 5,000-year-old craft

• The Japanese philosophy for a no-waste world

And now artisans have opened their studio doors to visitors, allowing travellers to learn how they are expanding the possibilities of traditional crafts. A customisable programme organised by the city takes visitors into workshops, including that of Kaga yūzen artist Hitoshi Maida, who incorporates contemporary approaches, such as geometric designs, in his kimonos.

Comprising elements of ceramics and lacquerware, the tea ceremony represents a culmination of traditional craftsmanship – Kobo students are required to spend two years studying chadō (the way of tea) and must craft all their own elements, from bowls to kimono. Again, it’s a legacy of the Maeda, who were particularly fond of the tea ceremony and wanted Kanazawa to be known for its highest expression, which meant producing the highest quality of utensils.

In 1666, the Maeda invited the first Ōhi Chōzaemon to Kanazawa, where he found a soft clay in a neighbouring village. Building on the techniques he’d learned in Kyoto, he used this clay to develop the free-wheeling style of pottery known as Ōhi ware. Today, visitors to the Ōhi Museum can select a bowl from its collection and drink tea from it in a room designed by Japanese starchitect Kengo Kuma.

The delicate setting of a tea ceremony typically makes me feel like a clumsy interloper and, at the museum, this sense is only heightened by handling a valuable work of art. But I want to better understand the practice that I’ve come to see as the key to Kanazawa’s craft heritage. So, the next morning, as pink plum blossoms herald spring’s arrival, I head for Kenroku-en, one of Japan’s “great three” gardens, established by the Maeda in their castle grounds in the late 16th Century. Here, in the Kenrokutei building where fourth Kaga daimyō Tsunanori Maeda received visitors with tea, Oceáne Dubuc and Makiko Uda are helping open up the practice to Japan’s modern and increasingly diverse society.

“The first time I joined a Japanese tea ceremony, nobody explained what to do,” says Dubuc, who is from Toulouse, France. “I was really stressed so I couldn’t appreciate it.” Hoping to break through this barrier, Dubuc realised, “We should share this tradition for it not to die.” While she whips matcha, Uda adds that Japanese culture is often misunderstood, “even by Japanese people”. Dubuc sits next to me and gently explains each element, from what to say when receiving the bowl to turning it to admire its artistry. Peeling back the curtain like this, Dubuc says “let(s) people enjoy it”.

When you understand the tea ceremony, I realise that there is much to enjoy. Dubuc and Uda explain that chadō is about appreciating and showing gratitude for a moment in time that will never exist in quite the same way again. I start to understand why this tradition can promote peace or at least, more realistically, inner peace. The way of tea, Dubuc says, referring to the philosophy of Sen no Rikyū, who raised the tea ceremony to an art form in the 16th Century, is “harmony”.

Art

The English Heiress Who Masterminded a Multimillion-Dollar Art Heist and Built Bombs for the IRA

|

|

“I remember thinking that if you’re involved in this, you need to accept the possibility that at the end of the day, you may have to kill people.” Rose Dugdale, then 70 years old, was huddled in a high-backed leather chair, hands folded in her lap, when she made this remark in a rare interview for a 2012 documentary series. With short gray hair and a red sweatshirt engulfing her small frame, Dugdale bore little resemblance to the independence fighter of her youth. “I tried to wrestle with that thought and dealt with it,” the English heiress-turned-militant recalled. “There can come a time when you may or may not want to kill people, but at the end of the day, it’s the only way to deal with them.”

Despite Dugdale’s willingness to kill for the cause of Irish independence from British rule, no lives were taken on January 24, 1974, when she and three accomplices hijacked a helicopter and dropped two makeshift bombs on a police station in Strabane, Northern Ireland. The amateurish explosives—packed into a pair of milk churns—failed to detonate. Dugdale’s next grand act in support of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) would be something more suited to her posh English background: art theft.

What led this University of Oxford-educated woman to stray from a life of comfort and privilege to militancy and a disdain for wealth? She was born Bridget Rose Dugdale in March 1941, to a father who was an underwriter for the insurance market Lloyd’s of London and a mother who was an heiress herself. Dugdale’s childhood involved horseback riding at Yarty, her family’s Devon estate, and attending the same finishing school as singer and actress Jane Birkin.

The turning point of Dugdale’s life was the debutante season of 1958, when she was one of 1,400 young women presented to Elizabeth II. (1958 was the last time this nearly 180-year-old tradition took place.) Dugdale found the festivities overindulgent and a waste of money, later saying, “It was as if you were being sold as a commodity. I didn’t enjoy it at all and really wanted to get out of it.” She cashed in her ticket to a new life by convincing her father to fund her education at Oxford the next year in exchange for her participation in the season’s events.

The 1960s saw Dugdale diverge from her parents politically, as she became wrapped up in the revolutionary spirit that had swept college campuses worldwide. Full of idealistic energy and imbued with a deep disdain for wealth and those who held onto it, she threw herself at the first worthy cause that crossed her path.

Dugdale’s activism began in the working-class town of Tottenham in North London in 1971, “a really difficult time in Britain and Ireland,” says Robert J. Savage, a historian at Boston College. “The government there is in crisis. Inflation is high, unemployment is high, there’s tremendous labor unrest. … The government was actually forced to create a three-day workweek because people couldn’t keep the lights on.” Now in her 30s, Dugdale was well off the path once envisioned by her parents, and she made quick work of exhausting her inheritance. She handed out heaps of money to poor, largely immigrant families trying to make rent and heat their homes for the winter.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/ae/3caee39a-e564-4396-bebd-85fe5b1cdd54/gettyimages-2098854757.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3c/ae/3caee39a-e564-4396-bebd-85fe5b1cdd54/gettyimages-2098854757.jpg)

Mirrorpix via Getty Images

But everything changed on January 30, 1972, when British soldiers fired on demonstrators in Derry, Northern Ireland, killing 13 unarmed civilians and injuring at least 15 others. Known as Bloody Sunday, the deadly attack proved to be a turning point in the Troubles, a sectarian conflict that devastated Northern Ireland between the late 1960s and the late 1990s.

“It’s a time when there’s an incredible amount of violence,” says Savage. Some left-leaning Brits grew convinced that they should support the IRA, which they believed was fighting “a war against an imperialist power.” As Dugdale explained in the documentary, after Bloody Sunday, “there was no question that you needed to do everything you could to support that cause, to free the Irish people.”

Dugdale funneled her remaining funds into firearms for the IRA, which she and her boyfriend Walter Heaton then ferried into Northern Ireland. When her inheritance ran dry, Dugdale turned to the only source she knew of to procure more funds: her parents. With Heaton, she embarked on her first art crime, stealing about £82,000 worth of art and silver (around $1 million today) from her family’s Yarty estate in June 1973.

The couple’s crime was quickly discovered, and they stood trial that October. Heaton was sentenced to six years in prison, while Dugdale received a two-year suspended sentence, as the judge deemed the chances that she would ever commit such a crime again remote.

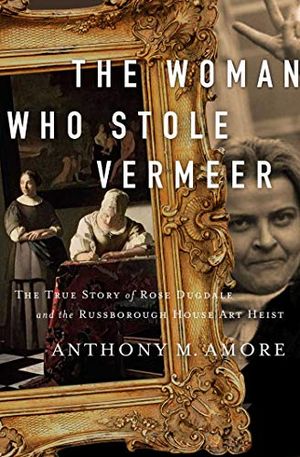

Anthony Amore, an art theft expert and the author of The Woman Who Stole Vermeer: The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist, says, “She was way ahead of her time—so far ahead of her time that no one would believe her. You have a judge say, ‘You’re unlikely to offend again, and surely you’re under the sway of this man.’”

By the spring of 1974, Dugdale had moved on to a new relationship with Eddie Gallagher, a member of the IRA’s paramilitary force, the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Alongside two other accomplices, Dugdale and Gallagher had recently carried out the botched bombing at Strabane, and they were now on the run. Laying low, Dugdale was busy planning what would become her most notorious act yet.

Her new target was Russborough House, the lavish County Wicklow, Ireland, home of Sir Alfred Lane Beit and his wife, Lady Clementine Beit. The Beits represented everything Dugdale despised: They were wealthy members of the British aristocracy, and their ancestral fortune had roots in the South African gold and diamond mining industry. The fact that the Beits had lived in South Africa and were vocally anti-apartheid didn’t stop Dugdale from targeting the treasure trove of fine art that adorned the walls of their mansion.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/34/8034248f-4f89-41da-a4c3-c7ba20bd7964/gettyimages-833523486.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/80/34/8034248f-4f89-41da-a4c3-c7ba20bd7964/gettyimages-833523486.jpg)

PA Images via Getty Images

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/2b/952b40cb-89aa-4457-9146-64c70114b509/clementine.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/95/2b/952b40cb-89aa-4457-9146-64c70114b509/clementine.jpg)

PA Images via Getty Images

Shortly after 9 p.m. on April 26, 1974, the Beits were listening to music in the library, oblivious to the doorbell ringing at the staff entrance. Servant James Horrigan greeted a woman with a thick French accent, who began complaining of car trouble. Suddenly, three masked men carrying assault rifles barged into the house behind Dugdale, who was disguised in a wig.

The four thieves made quick work of the Beits and their staff, tying the prisoners up in the library before taking Clementine down to the basement. Alfred made the mistake of looking up at one point, only to be struck on the head with the butt of a gun. Over the next ten minutes, Dugdale made her way around the estate, pointing out the most prized paintings to her companions and occasionally yelling “capitalist pig!” at Alfred.

The crew departed Russborough House with 19 works of art valued at an estimated £8 million (around $110 million today), including paintings by Francisco Goya, Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez. One of the stolen works, Woman Writing a Letter, With Her Maid, was one of just two Johannes Vermeer paintings under private ownership at the time. Dugdale and Gallagher hid with the paintings at a seaside cottage she’d rented in County Cork; the other two thieves fled elsewhere.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/80/8f801e69-056f-4cf4-9968-31a2c23c00c2/woman_writing_a_letter_with_her_maid_by_johannes_vermeer.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/80/8f801e69-056f-4cf4-9968-31a2c23c00c2/woman_writing_a_letter_with_her_maid_by_johannes_vermeer.jpeg)

One week after the heist, Gallagher left to secure a new hiding spot for the plunder. En route, he delivered a ransom note stating that the paintings would be returned in exchange for the transfer of four IRA members from a prison in England to one in Northern Ireland, as well as a payment of £500,000. If the demands weren’t met, all 19 masterpieces would be destroyed on May 14.

Meanwhile, authorities were combing the area, and the IRA was denying association with the theft. Albert Price, father of two of the prisoners mentioned in the ransom note, called the still-unidentified criminals “robbers covering up with excuses” and asked that the art be returned. His daughters, Marian and Dolours Price, had been convicted of a 1973 bombing and were on a hunger strike in an English prison when the robbery took place. They, too, urged the thieves not to destroy the priceless art.

On May 4, the Irish police stopped at Dugdale’s cottage as part of a routine canvas. Unconvinced by her fake French accent, they raided the rental while she was out, discovering incriminating material related to the theft. When Dugdale returned, they arrested her. Out of options, she surrendered quietly. Authorities found three of the stolen paintings in the cottage and the rest in the trunk of a car Dugdale had borrowed from the rental’s landlord.

In court, Dugdale entered a plea of “proudly and incorruptibly guilty.” She refused to name her accomplices and was sentenced to nine years in prison. Around this time, she discovered that she was pregnant with Gallagher’s child. Dugdale gave birth to a son named Ruairí on December 12, 1974, while imprisoned in Limerick.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/75/9975673d-4ff8-4d31-a268-ffd26e424ba1/tiede_herrema_1975.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/75/9975673d-4ff8-4d31-a268-ffd26e424ba1/tiede_herrema_1975.jpeg)

Rob Bogaerts / Anefo – Nationaal Archief via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0

Gallagher soon found himself on trial for an entirely different crime. In October 1975, he and fellow IRA member Marion Coyle kidnapped Dutch businessman Tiede Herrema in a failed attempt to ransom him for Dugdale and two other IRA prisoners. Herrema survived his 36 days in captivity unscathed; Gallagher was sentenced to 20 years in prison, Coyle to 15.

Dugdale and Gallagher made headlines again in 1978, when, after much petitioning, they became the first imprisoned couple to marry in the Republic of Ireland. Nevertheless, the pair grew estranged following Dugdale’s release from prison in 1980, after serving six years of her sentence.

Back on the outside, Dugdale moved with Ruairí to a cottage in the Coombe, a working-class Dublin neighborhood. Neighbors and friends often tended to Ruairí, while Dugdale wrote furiously for An Phoblacht, a newspaper published by the Irish republican political party Sinn Fein. She also helped drive the efforts of the IRA-backed group Concerned Parents Against Drugs, which sought to remove dealers from the streets during a heroin epidemic.

In 1985, Dugdale began a relationship with the married IRA bomb maker Jim Monaghan. The pair initially headed and taught courses for Sinn Fein’s education department but quickly turned to weapons development for the IRA. Their deadly innovations included empty bean cans converted into hand grenades, a homemade nitrobenzene replacement and a grenade launcher that used packets of digestive biscuits to minimize recoil. These weapons were used in attacks on West Belfast, a British army barracks in County Armagh and London’s Downing Street, where the IRA killed or injured dozens of police officers, government officials and innocent civilians.

Based on the life of Rose Dugdale, a former debutante who rebelled against her wealthy upbringing, becoming a volunteer in the militant Irish republican organisation, the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

BALTIMORE screens from March 22.

https://t.co/ae7AFzDFaA pic.twitter.com/as6W8jVcqm

— Light House Cinema (@LightHouseD7) March 15, 2024

As Dugdale continued her militant pursuits, an unsupervised Ruairí fell into the drug scene, selling ecstasy as a young man before emigrating to Germany in 1994 for a fresh start working in construction. “For [Dugdale], everything is the cause, and I think for her, whatever that cause might be, whatever path she decided to follow, would always take [precedence] over whatever personal relationship[s] she had in her life,” says Amore, the art theft expert.

Dugdale’s dedication to Irish independence led her to commit acts that landed her in prison. At the same time, it earned her the respect of Irish republicans who were initially skeptical of an English heiress. This grudging regard was evident last month, when Dugdale died in a Dublin nursing home at age 82. On March 27, a crowd of people clad in black bomber jackets and Easter Lilies gathered around the entrance to the Crematorium Chapel in Glasnevin, Ireland. From a black hearse, pallbearers wearing tricolor armbands carried a wicker casket holding Dugdale’s remains. Prominent IRA supporters, including Coyle and former Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams, came to say goodbye to their fellow revolutionary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/85/c385d3c0-580a-45d2-9828-a101bc5db9b6/gettyimages-2110556848.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/85/c385d3c0-580a-45d2-9828-a101bc5db9b6/gettyimages-2110556848.jpg)

Brian Lawless / PA Images via Getty Images

Fifty years after the art heist at Russborough House, Dugdale remains a divisive figure. “I always try to remember to tell people that she tried to commit a mass murder,” Amore says. “When they did that bombing that failed, if it had gone the way she planned, it would have been a slaughter of … innocent people.” But it’s also worth acknowledging the empathy Dugdale displayed toward the poor of Tottenham and believers in the Irish republican cause. Savage says, “She was a supporter of the peace process,” which brought three decades of unrest in Northern Ireland to a close in 1998. “She wasn’t a dissident in spite of the violence that she seemed to embrace.”

Dugdale’s characterization as a valiant freedom fighter or a violent criminal depends on whom you ask. “In Great Britain, people will see her as a terrorist,” says Savage. “Those that were victims of the IRA will see her as a terrorist and be appalled at the notion that she should be celebrated or embraced as a heroic character. But she, like others, will provoke admiration from some and … condemnation from others.” Ultimately, he concludes, “It’s a mixed legacy.”

For those who struggle to comprehend how an heiress could part with the advantages she was born into for a life of extreme, often militant advocacy, Amore is frank in his assessment, saying, “I think she was just wired differently than most people.”

Art

Standalone main art for A1 Examiner April 26, 2024

|

|

Artist Floyd Elzinga (right) poses for a selfie with Trent University’s Glennice Burns, associate vice-president international. They were celebrating Elzinga sculpture, Potential, at the entrance of the Trent University Symons Campus in Peterborough on Wednesday, April 24, 2024. ‘Potential’ is part of a pinecone sculpture series constructed of weathering steel and speaks to the cycle of regeneration and growth found in the untapped potential of seeds that offer renewal wherever they land.

-

Real eState24 hours ago

Montreal tenant forced to pay his landlord’s taxes offers advice to other renters

-

Media23 hours ago

B.C. online harms bill on hold after deal with social media firms

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoMOF: Govt to establish high-level facilitation platform to oversee potential, approved strategic investments

-

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours agoPolitics Briefing: Younger demographics not swayed by federal budget benefits targeted at them, poll indicates

-

News23 hours ago

Just bought a used car? There’s a chance it’s stolen, as thieves exploit weakness in vehicle registrations

-

Science22 hours ago

Science22 hours agoGiant prehistoric salmon had tusk-like spikes used for defence, building nests: study

-

Tech22 hours ago

Tech22 hours agoCalgary woman who neglected elderly father spared jail term

-

Real eState22 hours ago

Luxury Real Estate Prices Hit a Record High in the First Quarter