WINNIPEG – A steam locomotive made in 1882 and billed as Canada’s oldest operating one is in need of some tender loving care, and the volunteers who have kept it running on a vintage railway north of Manitoba’s capital are raising funds for the fixup.

Steam Locomotive No. 3, as it’s known, is neither efficient, fast nor energy-conscious compared with more modern locomotives. Shovelling coal into a fire to create steam leads to a lot of dirt, noise and thick black smoke. But for volunteers such as Paul Newsome, a train being powered by steam is unlike any other.

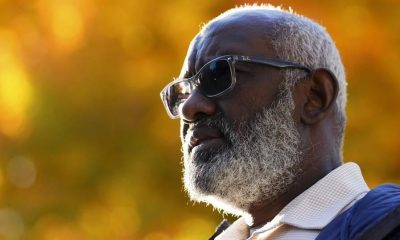

“A steam locomotive is alive, it feels alive. It makes noise, it smells and it responds to what you do to it,” Newsome, general manager of the Vintage Locomotive Society, said in a recent interview in the repair shop where No. 3 sits with its front section open, awaiting replacement tubes.

“You can see the results if you put in a lousy … fire, the steam doesn’t go up. It responds. And it’s almost human. As dumb as that may sound, it’s almost human.”

Newsome, 73, got the bug as a young boy. His grandfather was a railway man with Canadian National and retired in 1954. Newsome was taken along on his grandfather’s retirement ride, and he got hooked.

“Just to be involved with the steam locomotive after steam had quit being used on CN and CP in 1960 … was everything to me.”

Newsome’s career was in labour relations, but his passion for trains led him to volunteer on the vintage railway. Since 1970, he has given time and energy to the Vintage Locomotive Society, which had acquired No. 3 in time to have then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau take a ride as part of Manitoba’s centennial celebrations.

No. 3 was made in Scotland and delivered to Canadian Pacific via the United States, because the line through Canada north of Lake Superior had not been finished. In 1918, the locomotive was sold to Winnipeg Hydro, which kept it going until 1961.

The Vintage Locomotive Society acquired the locomotive in 1970 and has used it in the ensuing decades to take passengers on history-themed rides north of Winnipeg on its rail line, the Prairie Dog Central Railway.

Visitors sit in early 20th century coaches and get a taste of what travel was like on the bald prairie landscape before highways. The volunteers on the train can face heavy work. Shovelling coal can be hard labour. Newsome worked the fire and other tasks on the train until 2013 when health issues required him to ease up.

Passengers are taken one hour north to the Grosse Isle, where another volunteer organization runs a small historical village of period buildings.

“It helps the younger generation connect with a little bit of what life was like for their grandparents or even great-grandparents, coming from farming communities originally,” Donna Ridgeway, president of the Grosse Isle Heritage Site, said.

“Not many get that opportunity to go in an old house where everything wasn’t convenient or (see) what a school was like when all the grades were together.”

No. 3 is not running this year. A diesel locomotive has temporary taken its place.

No. 3 needs to swap out its entire set of 187 metal tubes — maintenance that is required every 15 years on steam engines. The tubes bring gases heated by the coal fire to the boiler, where water is heated to create steam. The steam creates pressure which, via pistons and rods, makes the wheels turn.

The repair work is expected to cost at least $150,000. The Vintage Locomotive Society’s budget took a severe hit during the COVID-19 pandemic when it couldn’t operate for two years. The group has set up a GoFundMe page, among other avenues, in hopes of raising the required money.

“So far it’s working out well, but we’ve got a little ways to go just yet,” Newsome said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 26, 2024