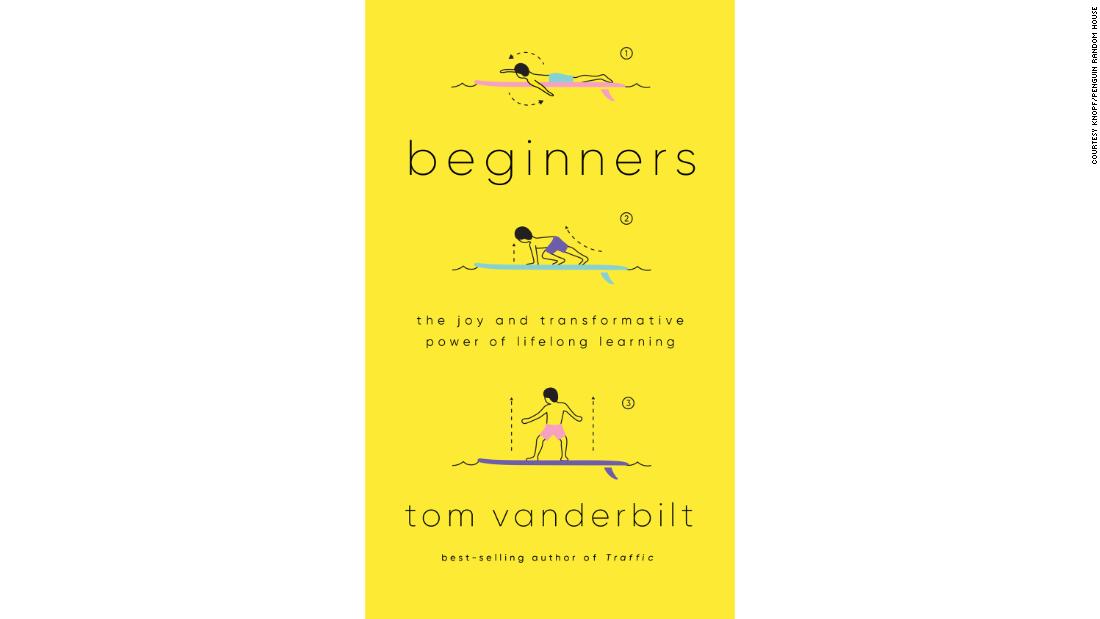

But as this was happening, I had the sudden realization that it was incredibly fun to learn some new skill — even if I wasn’t all that great at it — that if felt energizing, in the midst of middle age, to be a beginner again, something a lot of us largely leave behind when we’re young. There were a number of pursuits I’d always wanted to take a crack at, like singing and surfing, that I never got around too, for a variety of reasons: Time or money pressures, shyness, the anxiety of being bad at something in front of other people, the little voice in my head saying why bother, if it’s too late to make a real run at, or even turn it into some sort of side hustle.

In embarking on all these things, I discovered all kinds of benefits. They were all massively enjoyable to partake in, even to practice; they got me out of my own head, away from the screen. Even though I’m still not a great surfer or juggler, there was something powerful in simply experiencing progress, like I was reactivating some dormant muscle. I could feel my sense of self expanding as I pushed further into these pursuits; I was discovering more about the world, and myself. “We learn who we are in practice,” says the scholar

Herminia Ibarra, “not in theory.” And it’s almost an addictive process; once I started dabbling in new things, I felt as if there were nothing I wouldn’t try. I’d run out of reasons to tell myself “no.”

And I’ve come to believe that being an adult beginner is even a powerful parenting lesson. Here I was, telling my daughter how important learning for the sake of learning was, how she shouldn’t be afraid and simply plunge into new activities, when I myself hadn’t done so in what must have been decades. I was learning myself, struggling with the learning process but not giving up — and that, I think, is an important modeling tool. Don’t just be the parent sitting on the sidelines telling your kid they can do better. Learn something new yourself, go through the struggle, don’t give up. You’ll feel more empathy towards your kid’s learning journey, and they’ll see in you an example of the work that learning can take.

Cillizza: You talk a lot about the beginner’s mind in the book. What is it — and how can we apply it to politics?

Vanderbilt: Beginner’s mind is a concept, from Zen Buddhism, that refers to having the almost-childlike mindset of a beginner. The larger idea is that by being able to look at the world anew, without preconception, one might be able to gain wisdom that would otherwise be unavailable. “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities,” writes the Buddhist monk Shunryu Suzuki. “In the expert’s mind there are few.”

The potential consequences of this in the real world have been demonstrated in a number of academic studies, as in what’s been called the “earned dogmatism” effect: Basically, the idea that experts are allowed to be more closed-minded because, well, they’re experts. They’ve earned the right to rely on dogma, on what they’ve already learned. In one study, subjects were given a test of political knowledge. Some subjects were given falsely inflated scores, and those were the very same people who, in a subsequent test, demonstrated less “open-minded cognition,” defined as: “a tendency to select, interpret, retrieve, weigh, and elaborate upon information in a manner that is not biased by the individual’s prior opinion or expectation.”

This is not to say expertise is bad. The problem comes when dealing with new information, and there’s countless examples where experts have proven to be poor forecasters, because they’re not looking in the right place or they can’t see the change in front of them. This is where a “beginner’s mind,” the sort that children are naturally blessed with, can come in handy. As the psychologist

Alison Gopnik points out, children often notice changes in the environment because they have trouble not noticing. “We often say that young children are bad at paying attention. But what we really mean is that they’re bad at not paying attention, that they don’t screen out the world as grown-ups do.” The people who’ve often done better in trying to make forecasts, as

Philip Tetlock has pointed out, are “foxes” — people who know a little about a lot, versus “hedgehogs,” who know a lot about one big thing. The former group, being more dilettantish in their knowledge, is more open to question it.

The world of politics is, of course, filled with dogmatism, earned or not. People used to at least pay lip service to the old saying, “when the facts change, I change my mind.” Now there’s a tendency to simply ignore facts, or for people to come up with their own counter-factual worldview; they’re not changing their mind, but changing the facts to suit their mind (and it’s curious that lately it’s often the political novices, in a place like the US Congress, who seem to be the most dogmatic). What we need is more people, experts included, across the political spectrum, to admit that they still have things to learn.

Cillizza: One of the big things in the book is that we can keep learning at any age. Should that give some calm to people worried about President Joe Biden’s age — especially if he runs for a second term in 2024?

Vanderbilt: Every person is of course different, but the amazing phenomena of neural plasticity — literally the brain reshaping itself and adapting to new learning — is with us until we die. In the book, I encountered people well beyond my years who outperformed me in all sorts of tasks. We equate youth with learning and growth, and we fetishize the prodigy over the late-bloomer. I was intrigued by a comment one voice teacher made: She found it surprising that many people think it’s normal for a three-year-old to take private voice lessons, “yet it’s completely out of the question for someone 60 or older.” I’m not saying the old and the young are equally matched, but perhaps differently matched. When it comes to the brain, cognition slows, but wisdom grows.

Cillizza: Finish this sentence: “The biggest lesson my book taught me about human behavior is _____________.” Now, explain.

Vanderbilt: “People are not closed books.”

We begin so many things when we’re young. We try many different sports, we sing in the school choir, we draw, we’re told our horizons are endless. Over time, those horizons shrink; sometimes out of necessity, other times simply because we, or someone else, doesn’t believe we’re good enough to try our hand at something. Like a river flowing into a narrow canyon, there’s a sort of winnowing of experience, and it’s often difficult to swim upstream against that.

But we’re not done, our story’s not over. We may not become the next Picasso — no one can, he already was. But we can create things, move our body, express our voice and our vision, in our ways, in our time, at any age. Sometimes, people’s greatest passion is unlocked in some curious pursuit that’s totally outside what they normally do; the actor who throws pottery, the baseball player who starts a book club, the CEO who loves to do Ironmans. We shouldn’t think of these as distractions, or some watering down of who are, but our very strength.