Many experts say the huge pool of uninsured people in these states compounds the challenge of coping with the outbreak in several different ways, from leaving a large number of residents with underlying conditions that increase their vulnerability to the disease to extending the outbreak’s spread by discouraging the uninsured from seeking early testing and treatment.

The new pressures emerging as the virus migrates to low-insurance Sun Belt states — after striking first primarily in Northern and Western states that expanded Medicaid, almost all of which have lower uninsured rates than the national average — is only one of the several respects in which the outbreak is raising the stakes in the debate over the ACA’s future.

A new study from the Urban Institute suggests that the number of Americans relying on the ACA for coverage is growing as millions lose their jobs, and with it their employer-provided coverage, even as the Trump administration pursues a lawsuit that would overturn the law.

Nearly half a million Americans signed up for ACA policies after losing health insurance coverage this year, with surges in April and May.

All of this could make the political debate over health care even more central in 2020 than it was in 2018, when Democratic promises to defend the ACA, and in particular its provisions protecting patients with preexisting conditions, were pivotal in the party’s sweeping midterm election gains.

“All the same reasons that it was [important] in 2018 are in effect now, and all the [arguments] in the middle of a pandemic are even more potent,” says Democratic pollster Nick Gourevitch.

Republican pollster Gene Ulm disagrees. He says that concerns directly relating to the coronavirus outbreak — such as whether businesses and schools can reopen safely — are eclipsing all other issues this year. “All the oxygen has just been squeezed out,” he says. “Health care before meant, ‘Will I be able to get coverage? How much will I have to pay for it?’ Now it’s all the Covid.”

But Democrats are betting heavily that Ulm and other Republicans who share that perspective are wrong. Majority Forward, the issue advocacy arm of the Senate Democratic leadership, and the Senate Majority PAC, its campaign super PAC, are once again stressing health care more than any other issue in their advertising against Republican senators this year.

“I think health care — to the surprise of a lot of people, maybe most directly Republicans — is more urgent and even a greater priority than it was two years ago,” insists J.B. Poersch, the president and CEO of the Senate Majority PAC.

Many experts believe the pandemic and the ACA could be connected in an even more visceral way in the weeks ahead. The reason: Most expect that insurance companies are likely to define exposure to coronavirus as a preexisting condition. That means many of the millions of Americans who have contracted the disease could face higher premiums and less access to coverage and care if the administration’s lawsuit (and Republican legislative proposals throughout Donald Trump’s presidency) to repeal the ACA’s protections prevails.

“There’s no question in my mind that insurance companies would treat Covid-19 as a preexisting condition if they were allowed to,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. That prospect, he adds, “connects the dots in a very tangible way between the ACA and the pandemic.”

2018 vs. 2020

In the 2018 election, health care was central to Democratic gains.

In exit polls that year, almost three-fifths of voters said that Democrats would better protect patients with preexisting conditions — and those voters backed Democratic candidates in House races by almost exactly 10-to-1.

Democrats are again stressing the issue of preexisting conditions in House and Senate races this year. Majority Forward and the Senate Majority PAC have run television ads lashing GOP senators from Cory Gardner in Colorado and Martha McSally in Arizona to David Perdue in Georgia, Steve Daines in Montana and Thom Tillis in North Carolina for their votes earlier in Trump’s term to repeal the ACA and its measure barring insurers from selling coverage at higher prices to patients with preexisting conditions.

Although these ads haven’t specifically raised the prospect of insurers treating coronavirus exposure as a preexisting condition, t

hey have argued that the outbreak has heightened the need to protect Americans dealing with underlying health problems.

Republican senators have responded that they too are determined to guarantee that insurance companies cannot discriminate against patients with preexisting conditions. But they have not put forward a plan that would do so, even as

the Trump administration has asked the Supreme Court to invalidate the entire ACA, including its protections for patients with underlying health problems. Nonpartisan fact checkers have accused several of the GOP senators,

such as McSally, of distorting their record of voting to end the ACA’s protections.

These exchanges largely reprise the debate between the parties from 2018, albeit in the more highly charged atmosphere of the coronavirus crisis. But the outbreak — combined with the ACA lawsuit — may also be broadening the health care debate to focus more than in 2018 on the law’s efforts to expand coverage to the uninsured.

“When you talk about the sheer number of people that aren’t covered in a public health crisis, that is very relevant to the moment. That matters,” says Poersch.

Republicans are generally countering Democratic calls to protect the ACA or to expand coverage to the remaining uninsured by accusing the party of seeking a government takeover of health care.

“Democrats showed the entire country what their objectives are on health care during the presidential primary: a government-controlled plan that seeks to eliminate employer-based coverage,” Jesse Hunt, communications director for the National Republican Senatorial Committee, said in an email. “All roads lead to that outcome.”

The issue of ensuring coverage during a pandemic, particularly by expanding Medicaid, is surfacing in races around the country.

But the issue may be most pointed in the primarily Sun Belt states that have refused to expand Medicaid under the ACA and thus remain among the states coping with the largest share of uninsured residents even as their coronavirus caseloads spike.

States that fit at the center of that Venn diagram include North Carolina and South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida and Texas. All of them are

among the 13 remaining states that have not expanded Medicaid, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. In each of them

the uninsured share of the population exceeds the national average of 8.9%, with Texas (17.7%), Georgia (13.7%) and Florida (13%) all near the top of the list. And all are dealing with a furious surge in cases over the past few weeks.

Oklahoma, which ranks second in uninsured (at 14.2%), also placed on this list until voters there last month narrowly approved

a ballot initiative to require the state to expand Medicaid eligibility. (Though Arizona, another center of the outbreak, has expanded Medicaid, its share of uninsured adults remains about 20% above the national average.)

How they’re campaigning

In North Carolina, where Republican state legislators have repeatedly blocked efforts by Democrats to expand Medicaid eligibility, the Senate Majority PAC has stressed the issue in its advertising against Tillis, who before his election to the US Senate helped lead the fight against Medicaid expansion as the GOP speaker in the state House of Representatives.

“We’re in the middle of a public pandemic and public health is a crisis, and North Carolina has one of the highest percent of uninsured in the country because we’re one of the states that has not expanded Medicaid,” the Democratic Senate nominee,

Cal Cunningham, told McClatchy newspapers in late June.

In Alabama, Democratic Sen. Doug Jones, who faces a difficult fight for reelection in a state where Trump romped in 2016, is running an ad where he endorses Medicaid expansion for the state and declares: “Too many folks face the Covid crisis without health care coverage.”

In Texas, the issue is especially acute, both because it is the largest state that has not expanded Medicaid and because Republican Attorney General Ken Paxton has led the coalition of GOP states suing to invalidate the ACA. Democratic House candidate Sri Preston Kulkarni, who is running strongly for an open Republican seat outside Houston, one of the outbreak’s epicenters, has stressed health care throughout his campaign and unequivocally insisted that Texas should expand Medicaid eligibility.

Likewise, Democrats are promising to expand Medicaid in their uphill, but achievable, bid to win control of Texas’ state House of Representatives for the first time in years. Texas’ coronavirus crisis “has brought in a very crystallized way the reality of what life is with health care, and what life is without it,” says Democratic state Rep. Trey Martinez Fischer of San Antonio.

Contrary to the Democrats, Ulm says that in his research voters are not linking the outbreak with either the debate over protecting preexisting conditions or Trump’s efforts to repeal the ACA. “It’s not how people are looking at it,” he says. “It’s just not. They are looking at it more like: No one seems to understand this [disease].”

But Republican candidates do seem to be hedging their bets on the ACA. Several are seeking to reframe their record of voting against it, and not only by insisting that they, too, support protections for people with underlying health conditions. In North Carolina,

Tillis responded to Cunningham’s criticism of his role in blocking Medicaid expansion by declaring that his earlier objections have left “North Carolina in a better position to expand it today if state leaders choose to do so.” Though

McSally helped rally House Republicans with a memorable expletive before their 2017 vote to repeal the ACA,

she now is airing an ad where a supporter promises she will “make sure every Arizonan has quality affordable health care.”

Such repositioning may reflect the enormous pressure that the coronavirus outbreak is imposing on health care systems, particularly in the states already strained by the large number of uninsured. The big uninsured population “makes it exponentially worse” to cope with the surge, says Texas state Rep. Fischer Martinez.

Challenges for non-expansion states

Medical experts say that the Sun Belt states have one big advantage over the states hit earlier this spring: Hospitals have developed more expertise on how to treat victims and reduce mortality. But in many other respects, experts say the large number of uninsured in many of these states complicates their situation. These challenges include:

- The states with the largest share of uninsured also tend to be among those where the highest share of the population suffers from underlying health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes and obesity, that put them at elevated risk of serious health consequences if they contract coronavirus, according to a recent Kaiser analysis. And, according to an Urban Institute analysis for me of 2018 census data, African Americans and Hispanics — two groups suffering disproportionately in the outbreak — are far more likely than Whites to be uninsured in those same states. In Texas, for instance, Blacks are about 50% more likely than Whites to lack health insurance, and Hispanics are almost three times as likely. In Florida, Blacks are about 40%, and Hispanics about 75%, more likely than Whites to be uninsured.

- People without health insurance tend to put off seeking care until it is absolutely unavoidable, experts note. That could make them more reluctant to pursue testing for coronavirus at the first indication of symptoms — extending the time they are circulating the disease in the community. Many of the uninsured “won’t go get care because they assume they’re not going to get it,” says Vivian Ho, a health care economist at Rice University and the Baylor College School of Medicine in Texas. “I have no doubt that’s a good portion of why the disease is spreading here.”

- More uninsured receiving coronavirus care increases the financial strain on hospitals, already reeling from the severe decline in revenue for other services as potential patients avoid seeking medical care during the outbreak. The federal government has allocated a substantial $175 billion to support medical providers during the crisis, with about half of that earmarked for hospitals; but as the number of coronavirus patients without health insurance mounts, “that’s going to increase the financial stress,” says Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association. “At the rate we’re going, none of this relief is going to make anybody whole.” The administration has promised to reimburse providers for treating the uninsured out of the relief money. On Friday, the Department of Health and Human Services said that it’s paid $340 million so far to hospitals that have submitted claims for treating the uninsured. HHS said it’s less than it had expected but that hospitals can continue to submit claims.

- These financial strains could increase the risk that more hospitals will close, especially in states where the decision not to expand Medicaid has already placed smaller and rural hospitals at risk. “The public health crisis, combined with the economic crisis, has put many health care providers, especially in states that have not expanded Medicaid, at greater financial risk,” says Levitt, of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

- With studies suggesting that lingering health problems afflict a significant portion of coronavirus victims who survive the disease, experts worry that many of the uninsured lack the regular source of care required for follow-up treatment.

The final twist in the debate is evidence that more Americans are relying on the ACA for their health care amid the massive layoffs triggered by the virus.

In its recent study, the Urban Institute found that among those laid off this spring, the share still receiving health insurance from employers (either their own or family members’) had declined. While many of those were moving into Medicaid or subsidized private coverage on the Affordable Care Act exchanges, “There’s a risk that as the job losses continue you will see that gap widen in health insurance coverage between the [Medicaid] expansion and non-expansion states,” says Michael Karpman, an Urban Institute senior research associate.

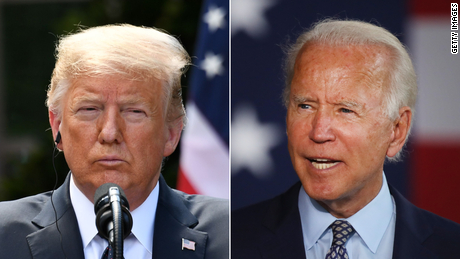

In the presidential race, the coronavirus outbreak has eclipsed all other issues to the point that the health care debate hasn’t been engaged as directly as in many of the Senate and House contests. But the virus’ turn into the low coverage states that refused to expand Medicaid could eventually provide a vivid backdrop for one of the sharpest policy differences between Trump and presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden.

While

Trump is asking the Supreme Court to invalidate the entire ACA, including the Medicaid expansion,

Biden’s health care plan would automatically extend federally provided coverage to all low-income adults in the states that have rejected the expansion. As the raging coronavirus outbreak threatens Trump’s support in Sun Belt states that he won in 2016 — particularly North Carolina, Florida, Georgia and Texas — that’s a distinction Democrats may highlight more before Election Day.

CNN’s Tami Luhby contributed to this report.