Art

Your Prescription: Look at Art

|

|

Art therapists today help their patients cope with anxiety, addiction, illness, or pain. Therapists might encourage clients to explore their emotions by drawing, for example, or to reflect on a difficult experience through painting. Art is used to help people express themselves and explore their emotions.

In past centuries, however, art therapy took a substantially different form. Maybe it’s time to bring this practice of the past into the present—as a way to move into the future.

The Isenheim Altarpiece is a 16th-century sculpted and painted work housed in an old convent-turned-museum in the medieval city of Colmar, France—a city with wood-framed houses and winding footpaths that appear to have changed little in 500 years.

Altarpieces have long been used to decorate churches and to tell stories, but the Isenheim Altarpiece offered an additional therapeutic function. The religious order that cared for the sick, the Antonites, “prescribed” viewing the altarpiece to those in their hospitals. They led the sick to the choir area of the Isenheim church, where they provided them with fresh bread and saint vinage, an herb-infused wine. In this quiet space, patients could meditate on the paintings that comprised the altarpiece.

The Isenheim Altarpiece’s central panel displayed a plague-infected crucified Christ. For Europeans in the Middle Ages, religious art held a particular power over the social imagination: Patients sick with bubonic plague would have derived great consolation from the image of Christ similarly afflicted. The painting told them Christ’s body was ruined like theirs, that he understood their suffering, and that they were not alone. It silently relieved some of the deepest anxieties of the sick and dying: decay of the body, pain, isolation.

Over the centuries, the Isenheim Altarpiece has continued to impress artists and writers. American novelist Francine Prose was particularly astonished by its use as art therapy. She described viewing the altarpiece as life-changing and said she was surprised to discover, “at some point in our history, a society thought that this was what art could do: that art might possibly accomplish something like a small miracle of comfort and consolation.”

Could art still accomplish a miracle of comfort and consolation today? Could it remind people of their mortality while also mitigating fear? Could it foreshadow the inevitable while also instilling hope?

When the Antonites prescribed viewing the Isenheim Altarpiece, it was meant to be life-changing. The sick ate bread, drank wine, and metaphorically consumed the painting. And that consumption allowed for personal transformation. Patients opened themselves up to the image of the dying Christ and received comfort through solidarity.

Today, we also consume art. Indeed, the Isenheim Altarpiece now sits in a world-class museum on display for those who can pay. But do we let art transform us? Do we allow art to remind us of our finitude and comfort us in our brokenness? Or do we see it merely as pay-for-view works of creative expression—or, worse still, its possession as a symbol of social status? Do we own art, but refuse to let it shape us?

I was of the persuasion that art had perhaps been irredeemably commodified, along with the rest of what is good, true, and beautiful in life. And then I went to France to see the altarpiece for myself.

Space does not permit its adequate description. The altarpiece’s multiple layers, stories, sculpture, and painting are all so rich. What I saw in France confirmed for me that the masterpiece continues to exert its life-changing influence. Art can still perform miracles of comfort and consolation.

I spent my day in Colmar scrutinizing the Isenheim Altarpiece from all angles. I had prepared in advance, and I drew on my research to take in its every feature.

At the end of the day, I went up to the balcony overlooking the work. I had examined its detail. Now I wanted to take it all in at once. But from my view above, it wasn’t the painting that captured my attention.

The hour was late, and the museum was nearly empty. Only two people remained. A thin middle-aged man who walked with a cane shuffled slowly from panel to panel. It was as if he were loath to leave and was trying to squeeze every last drop out of his medicine. On a bench sat a tiny elderly lady with loose white curls who was meditating on the disfigured Christ. The two of them were captivated, and I was captivated by their captivation. Broken and aged as they were, they were drinking in the beauty of art and receiving consolation of a different dimension.

Source:- Psychology Today

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

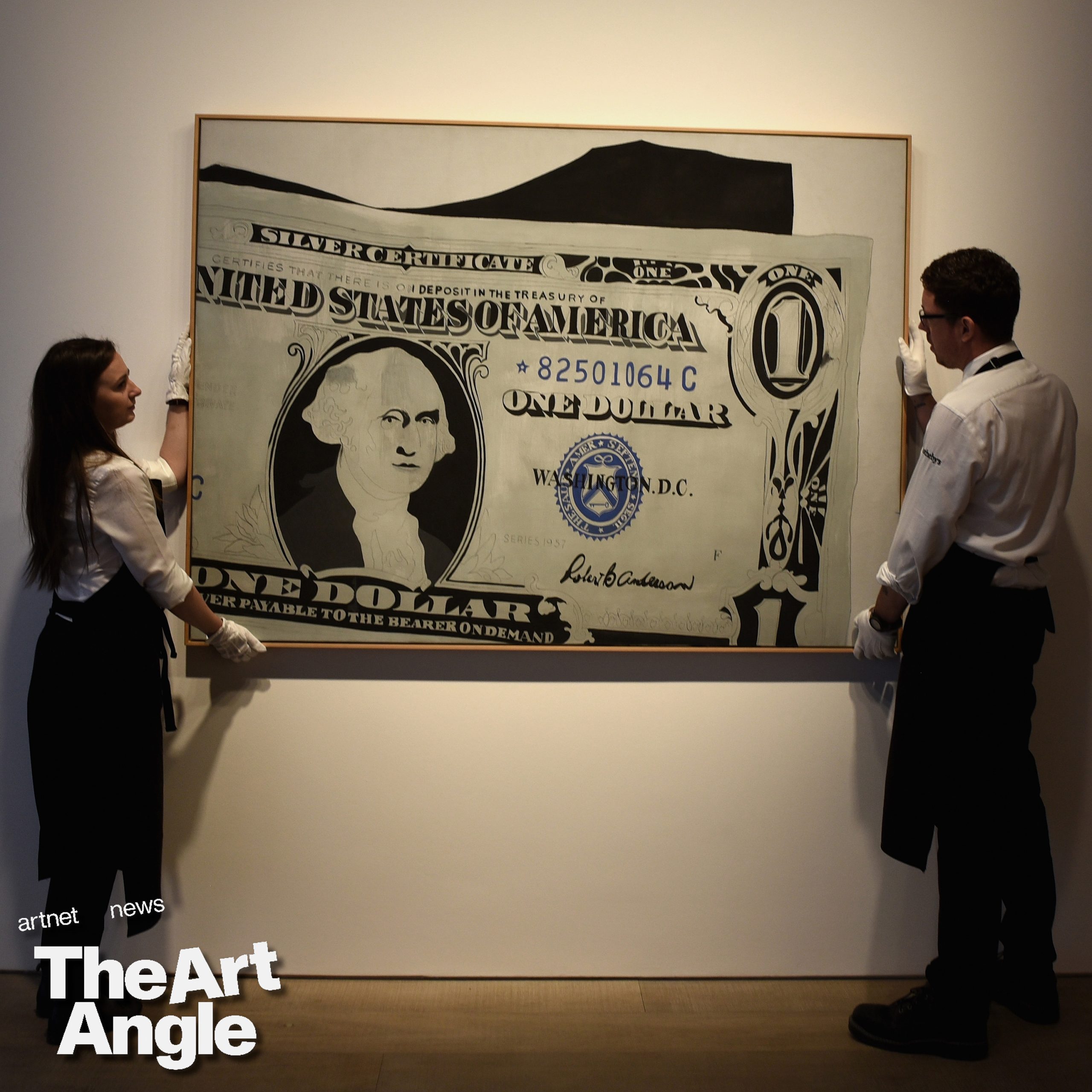

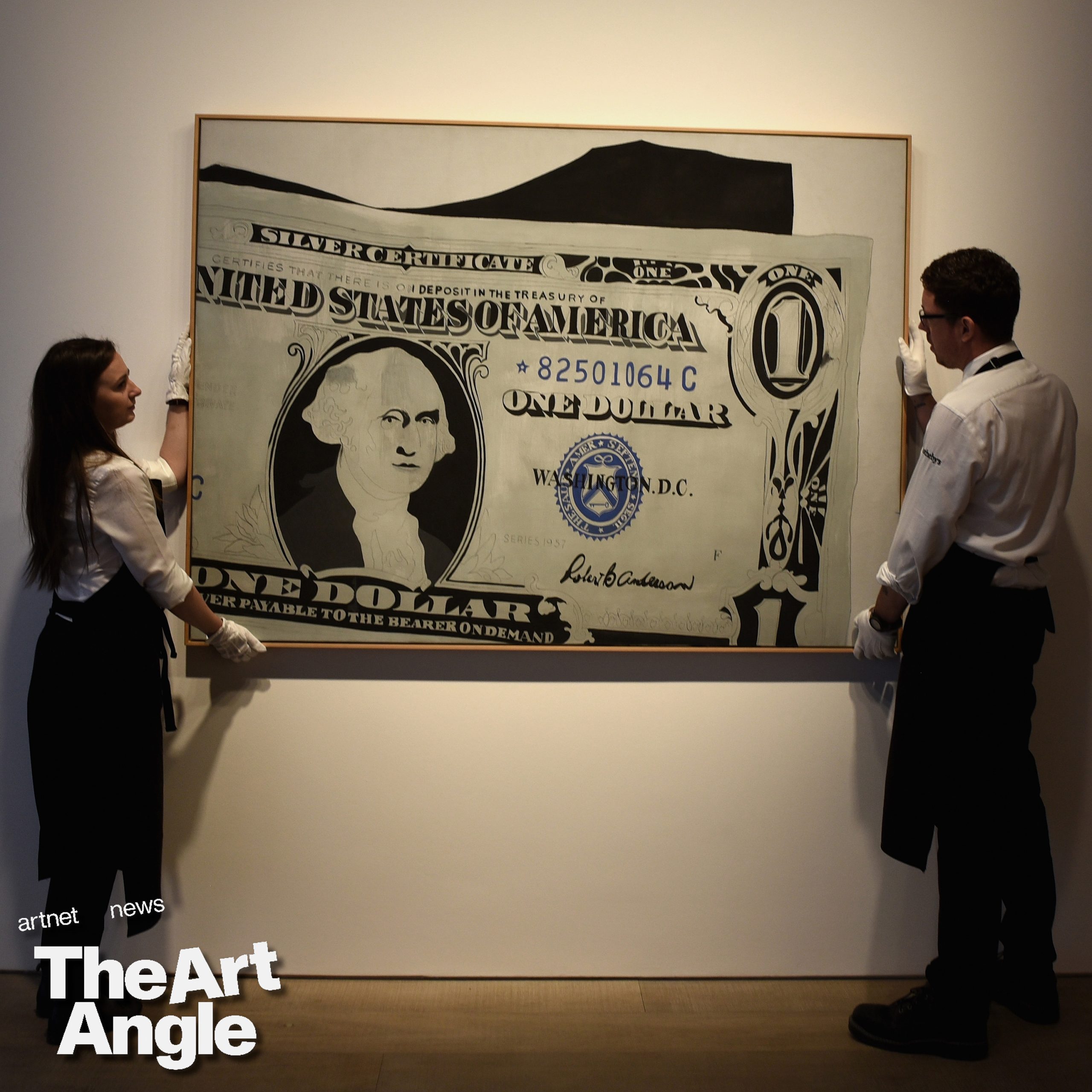

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media17 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media19 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment18 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

-

News16 hours ago

Canada Child Benefit payment on Friday | CTV News – CTV News Toronto

-

Real eState10 hours ago

Botched home sale costs Winnipeg man his right to sell real estate in Manitoba – CBC.ca

-

Business18 hours ago

Gas prices see 'largest single-day jump since early 2022': En-Pro International – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Art21 hours ago

Enter the uncanny valley: New exhibition mixes AI and art photography – Euronews