Art

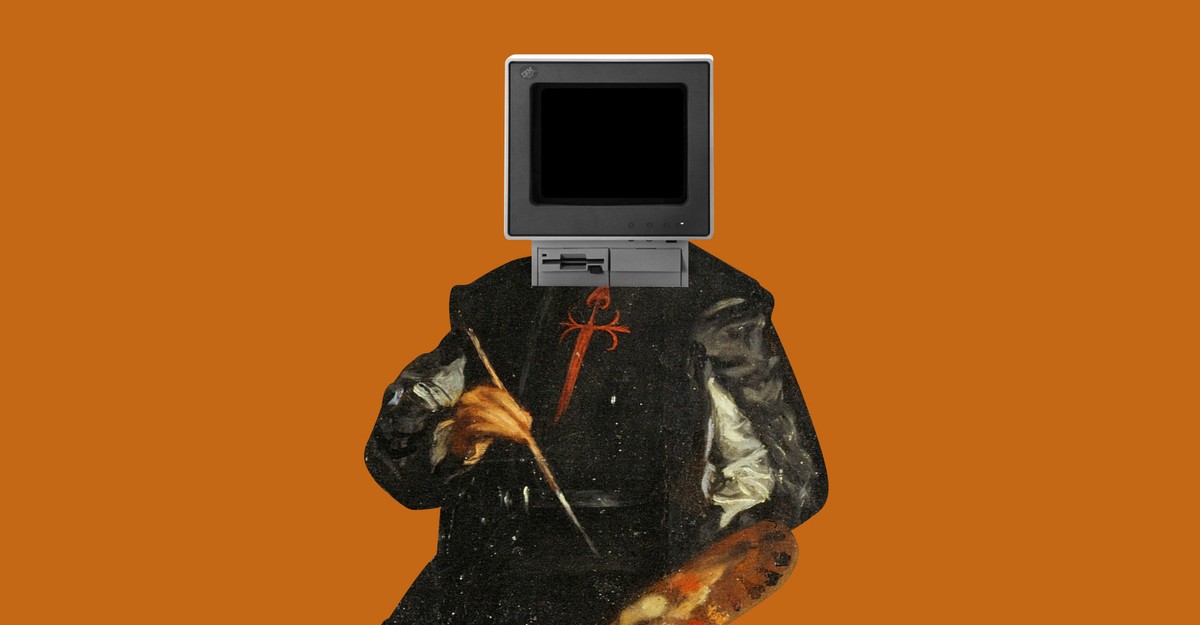

Is AI Art a 'Toy' or a 'Weapon'? – The Atlantic

Earlier this year, the technology company OpenAI released a program called DALL-E 2, which uses artificial intelligence to transform text into visual art. People enter prompts (“plasticine nerd working on a 1980s computer”) and the software returns images that showcase humanlike vision and execution, veer into the bizarre, and might even tease creativity. The results were good enough for Cosmopolitan, which published the first-ever AI-generated magazine cover in June—an image of an astronaut swaggering over the surface of Mars—and they were good enough for the Colorado State Fair, which awarded an AI artwork first place in a fine-art competition.

OpenAI gave more and more people access to its program, and those who remained locked out turned to alternatives like Craiyon and Midjourney. Soon, AI artwork seemed to be everywhere, and people started to worry about its impacts. Trained on hundreds of millions of image-text pairs, these programs’ technical details are opaque to the general public—more black boxes in a tech ecosystem that’s full of them. Some worry they might threaten the livelihoods of artists, provide new and relatively easy ways to generate propaganda and deepfakes, and perpetuate biases.

Yet Jason Scott, an archivist at the Internet Archive, prolific explorer of AI art programs, and traditional artist himself, says he is “no more scared of this than I am of the fill tool”—a reference to the feature in computer paint programs that allows a user to flood a space with color or patterns. In a conversation at The Atlantic Festival with Adrienne LaFrance, The Atlantic’s executive editor, Scott discussed his quest to understand how these programs “see.” He called them “toys” and “parlor game[s],” and did a live demonstration of DALL-E 2, testing prompts such as “the moment the dinosaurs went extinct illustrated in Art Nouveau style” or “Chewbacca on the cover of The Atlantic magazine in the style of a Renaissance painting” (the latter of which resulted in images that looked more canine than Wookiee). Scott isn’t naive about the greater issues at play—“Everything has a potential to be used as a weapon”—but at least for a moment, he showed us that the tech need not be apocalyptic.

Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Watch: Atlantic executive editor Adrienne LaFrance in conversation with Jason Scott

Adrienne LaFrance: When we talk about AI art, what do we even mean? How does it work?

Jason Scott: So what we’re calling “AI art”—by the way, they’re now calling it “synthetic media”—it’s the idea of using analysis of deep ranges of images, not just looking at them as patterns or samples, but actually connecting their captions and their contexts up against pictures of all sorts, and then synthesizing new versions from all that.

LaFrance: So basically a giant database of images that can be drawn from to call to mind the thing that you prompt it to make.

Scott: Right.

LaFrance: And why is it exploding now? It seems like various forms of machine learning and AI have really accelerated in recent years.

Scott: They let it out of the lab and let regular people play with the toys. Across the companies that are doing this, some are taking the model of We’ll let everyone play with it now—it’s part of the world.

LaFrance: When you think about the implications for this sort of technology, give us an overview of how this is going to change the way we interact with art, or whatever other industries come to mind. For instance, at The Atlantic we have human artists making art. I’m sure they might have strong feelings about the idea of machines making art. What other industries would be potentially affected?

Scott: Machines are becoming more and more capable of doing analysis against images, text, music, movies. There are experimental search engines out there that you can play with and say things like “I need to see three people around a laptop.” And previously it would have to be three people in the laptop, but it actually is starting to make matches where there’s three people in the room. And the weirder and more creative you get with this toy, the more fun it gets. I see a future where you’ll be able to say, “Could I read a book from the 1930s where it’s got a happy ending and it takes place in Boston?” Or, “Can I have something where they fell in love but they’re not in love at the end?”

LaFrance: I have more questions, but I think now it’d be a good time to start showing people what we mean. Do you have some examples?

Scott: I have some examples of things that I did. So this is “detailed blueprints on how to build a beagle.”

“Detailed blueprints on how to construct a beagle” pic.twitter.com/blZSVJyMXd

— Jason Scott (@textfiles) July 15, 2022

LaFrance: So these are prompts that you gave the model, and this is what came out of it?

Scott: Yes. For the people who don’t know how this whole game works, it’s pretty weird. You usually type in some sort of a line to say, “I’m looking for something like this,” and then it creates that, and then people get more and more detailed, because they’re trying to push it. Think of it less as programming than saying to somebody, “Could you go out there and dance like you’re happy and your kid was just born?” And you’ll watch what happens. So it’s kind of amorphous. This is a lion using a laptop in the style of an old tapestry. This is Santa Claus riding a motorcycle in the style of 1970s Kodachrome. This is Godzilla at the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This is a crayon drawing of a labor action. These are bears doing podcasts. This is GoPro footage of the D-Day landing.

I’m always playing with it, and the reason you’re hearing all those strange prompts from me is because I want to understand: What are these systems seeing? What are they doing? It’s so easy as a parlor game to say, “Draw a cellphone as if it was done as a Greco-Roman statue.” But what about doing a bittersweet sky, or trying to draw a concerned highway? What does it see?

LaFrance: What does this suggest to you about the nature of art? This gets to be sort of an existential question, but is it still human-made art in the way that we think of it, and should we be bothered by that? I mean, we use all sorts of tools to make art.

Scott: Everyone is super entitled to their own opinion. All I can say is, I did drawings in a zine in my teens; I was a street caricaturist; my mother was a painter; my father does painting; my brother’s a landscape artist. And coming from that point of view, I am no more scared of this than I am of the fill tool or the clone brush [in Photoshop]. Everything has a potential to be used as a weapon—imagery, words, music, text. But we also see an opportunity here for people who never knew that they had access to art. I can almost hear the gears crack and start moving again when I go to somebody and I’m like, “Could you give me something to draw?” And they do it and they see how it goes. I can’t get angry at that particular toy. But I won’t pretend that this toy will stay in its own way neutral, or even is neutral now.

LaFrance: I was talking to a colleague about these sorts of tools the other week, and we were really compelled by the idea of being able to visualize dreams. What other sorts of things—fiction comes to mind—can we imagine but don’t normally get to visualize?

Scott: I love telling these AIs to draw “exquisite lattice work”—using phrases like exquisite or rare—or give me “leather with gold inlay on a toaster,” and watching it move into that world and design things in seconds that aren’t perfect, but are fun.

LaFrance: We’re going to experiment, which is always dangerous. You’re never supposed to do stuff in real time. But I have some prompts for you.

Scott: This is DALL-E. There are many others. Think of it just like early web servers or early web browsers. There’s a bunch of companies with various people funding them or doing things their own way.

[Scott now leads LaFrance through a demonstration of DALL-E 2: It’s included in the video embedded above.]

Scott: We see the ability to do everything from intricate pen-and-ink drawings to cartoons. People are using it now to make all sorts of textures for video games; they are making art along a theme that they need to cover an entire wall of a coffee shop; they’re using it to illustrate their works. People are trying all sorts of things with this technology and are excited by it.

Art

Calvin Lucyshyn: Vancouver Island Art Dealer Faces Fraud Charges After Police Seize Millions in Artwork

In a case that has sent shockwaves through the Vancouver Island art community, a local art dealer has been charged with one count of fraud over $5,000. Calvin Lucyshyn, the former operator of the now-closed Winchester Galleries in Oak Bay, faces the charge after police seized hundreds of artworks, valued in the tens of millions of dollars, from various storage sites in the Greater Victoria area.

Alleged Fraud Scheme

Police allege that Lucyshyn had been taking valuable art from members of the public under the guise of appraising or consigning the pieces for sale, only to cut off all communication with the owners. This investigation began in April 2022, when police received a complaint from an individual who had provided four paintings to Lucyshyn, including three works by renowned British Columbia artist Emily Carr, and had not received any updates on their sale.

Further investigation by the Saanich Police Department revealed that this was not an isolated incident. Detectives found other alleged victims who had similar experiences with Winchester Galleries, leading police to execute search warrants at three separate storage locations across Greater Victoria.

Massive Seizure of Artworks

In what has become one of the largest art fraud investigations in recent Canadian history, authorities seized approximately 1,100 pieces of art, including more than 600 pieces from a storage site in Saanich, over 300 in Langford, and more than 100 in Oak Bay. Some of the more valuable pieces, according to police, were estimated to be worth $85,000 each.

Lucyshyn was arrested on April 21, 2022, but was later released from custody. In May 2024, a fraud charge was formally laid against him.

Artwork Returned, but Some Remain Unclaimed

In a statement released on Monday, the Saanich Police Department confirmed that 1,050 of the seized artworks have been returned to their rightful owners. However, several pieces remain unclaimed, and police continue their efforts to track down the owners of these works.

Court Proceedings Ongoing

The criminal charge against Lucyshyn has not yet been tested in court, and he has publicly stated his intention to defend himself against any pending allegations. His next court appearance is scheduled for September 10, 2024.

Impact on the Local Art Community

The news of Lucyshyn’s alleged fraud has deeply affected Vancouver Island’s art community, particularly collectors, galleries, and artists who may have been impacted by the gallery’s operations. With high-value pieces from artists like Emily Carr involved, the case underscores the vulnerabilities that can exist in art transactions.

For many art collectors, the investigation has raised concerns about the potential for fraud in the art world, particularly when it comes to dealing with private galleries and dealers. The seizure of such a vast collection of artworks has also led to questions about the management and oversight of valuable art pieces, as well as the importance of transparency and trust in the industry.

As the case continues to unfold in court, it will likely serve as a cautionary tale for collectors and galleries alike, highlighting the need for due diligence in the sale and appraisal of high-value artworks.

While much of the seized artwork has been returned, the full scale of the alleged fraud is still being unraveled. Lucyshyn’s upcoming court appearances will be closely watched, not only by the legal community but also by the wider art world, as it navigates the fallout from one of Canada’s most significant art fraud cases in recent memory.

Art collectors and individuals who believe they may have been affected by this case are encouraged to contact the Saanich Police Department to inquire about any unclaimed pieces. Additionally, the case serves as a reminder for anyone involved in high-value art transactions to work with reputable dealers and to keep thorough documentation of all transactions.

As with any investment, whether in art or other ventures, it is crucial to be cautious and informed. Art fraud can devastate personal collections and finances, but by taking steps to verify authenticity, provenance, and the reputation of dealers, collectors can help safeguard their valuable pieces.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoAlberta Premier Smith aims to help fund private school construction

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoHealth Minister Mark Holland appeals to Senate not to amend pharmacare bill

-

Economy12 hours ago

Economy12 hours agoN.B. election: Parties’ answers on treaty rights, taxes, Indigenous participation

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoNova Scotia NDP accuse government of prioritizing landlord profits over renters

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoSleep Country shareholders approve sale to Fairfax Financial

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoNurse-patient ratios at B.C. hospitals set to expand in fall, says health minister

-

Economy12 hours ago

Economy12 hours agoConstruction wraps on indoor supervised site for people who inhale drugs in Vancouver

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoSecond-half goals lift defending MLS champion Columbus past Toronto FC