Remembering the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Health

Accent: How Sudbury coped with the Spanish flu 100 years ago – The Sudbury Star

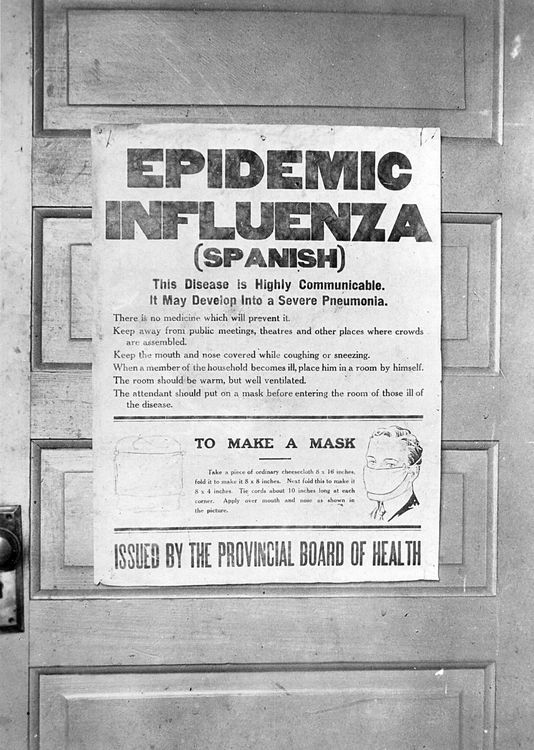

This 1918 board of health influenza poster in Alberta would have been typical for the Spanish flu pandemic. In Sudbury, the pandemic infected thousands and killed hundreds. File photo

“’FLU’ EPIDEMIC BRINGS CLOSURE ALL ASSEMBLIES – Civic Authorities in Endeavor To Cope With Disease,” was the front-page headline for the Sudbury Star on Oct. 16, 1918.

The 1918 Flu Pandemic (1918-1920), also known as the “Spanish Flu” or “La Grippe,” spread to Canada that September and Sudbury had its first case by early October. While staying at home and practising social distancing, take some time to learn about Sudbury’s experience with a pandemic a little over 101 years ago.

The 1918 influenza pandemic was caused by an H1N1 virus. The exact place of origin is unknown but the virus started during the last months of the First World War and quickly spread around the world.

Spain was not the first country to experience the virus, but, as a neutral country during the war, officials there reported openly about the disease, which may have led to the virus being called the “Spanish Flu.”

Globally, the virus infected about one-third of the population with an estimated 50 million deaths.

By Oct. 9, 1918, there were at least 12 cases of the disease in Sudbury with eight of them classified as “more severe.” All cases were traced to outside sources, so the virus was not yet community spread.

The Sudbury Board of Health recommended the public to isolate anyone infected, maintain health with exercise in the fresh air, proper nutrition and sleep, washing hands prior to eating, avoiding crowds and not kissing anyone.

It was also recommended that “the hands should be kept away from the mouth and nose at all times … The nose and mouth should always be covered with a handkerchief in the act of coughing or sneezing.”

Anyone caring for someone infected was not to touch their face or mouth with their hands while handling a patient or infected items. In addition to many other stipulations, caregivers were to wash their hands with soap, water and a nail brush, and hold their hands for five minutes in antiseptic solution before interacting with healthy people.

Huron women between the ages of 16 and 35 suffered the highest mortality rates for the Spanish Influenza. They tended to be the caregivers in the home and community. Submitted

jpg, GS

Just three days after the virus was first reported in Sudbury, St. Joseph’s Hospital was full, except for a few beds in the public ward. Eventually, Sudbury High School was transformed into a temporary emergency hospital to be used if needed.

The province began to consider allowing the purchase of small quantities of alcohol for medicinal purposes without a doctor’s note. A local milk shortage, which started just before the virus arrived in town, was exacerbated, in part, by the flu.

The board of health asked Sudburians to stay home if infected and to leave the hospital for those without homes in town.

Within four more days, the number of infected increased to 500 to 800, and five of those with the virus had died due to pneumonia.

Local doctors found that while about 85 per cent of cases were very mild, 15 per cent were severe.

On Oct. 16, 1918, all public places in town were closed, including schools, churches, theatres, the public library, lodges, the market place, etc. and the CNR station platforms were limited to only those with necessary business.

The Sudbury-Copper Cliff Electric Railway was required to clean its cars and fumigate them daily and passenger capacity was cut in half. Restaurants remained open, but with a limit of 25 patrons. The post office also remained open, but loitering or congregating in the post office, street corners, office buildings, etc. was forbidden as was spitting in public places.

Fortunately, isolation had the desired effect. While there were many new cases, within a few days the number of new daily cases decreased. By October 23, 1918, there were more 1,000 cases in town and 41 deaths from the virus since the beginning of the month.

An experimental inoculation was sent to Sudbury doctors from Toronto to administer 5,000 doses.

By early November, there were around 1,500 to 1,800 cases in Sudbury. There were also about 1,100 to 1,200 cases “among the mining towns of the International Nickel Co.” Copper Cliff had suffered six deaths from the virus by this time and Burwash Industrial Farm had 16 deaths by mid-November, but many other towns were spared. Garson stopped all incoming and outgoing traffic and as of Nov. 2, 1918, had no cases of the disease.

On November 10, 1918, the places of worship were re-opened in Sudbury and the following day most public places. The public library and schools opened a week later.

There were still new cases but they were much milder and the numbers fell by November 20, 1918, to less 10 new cases a day. By early December, Sudbury had experienced about 2,000 cases with around 65 local deaths from the disease in addition to an unknown number of deaths of people brought to town for treatment.

These numbers are approximate as it was not required in 1918 to report cases of the disease and by late November, statistics were no longer included locally in media reports.

From the beginning of October to the end of December 1918, death records indicated around 190 deaths in Sudbury due to “Influenza,” “La Grippe” or “Spanish Influenza.”

(There were cases of influenza or la grippe in town at this time that were not the Spanish Influenza, so some of these deaths may have been from the seasonal flu. There were about 26 death records in Sudbury that listed specifically “Spanish Influenza” as a cause of death from October to December 1918 but media reports were much higher so it is possible physicians sometimes shortened it to “influenza.” During the same time period, “pneumonia” was also recorded locally as a cause of death in a number of cases.)

Death records continued to list Spanish Influenza as a cause of death in Sudbury until the end of February with an additional eight deaths. January to March 1919 also included 31 deaths due to “Influenza” in town and one death due to “Influenza” in June in Sudbury.

There was also one individual in 1920 listed as died of the “Spanish Influenza” in Sudbury and at least 67 Sudburians who died of “Influenza” or “La Grippe.”

There was also one additional death of a person in Sudbury with the official cause listed as “Spanish Influenza” in 1921 and at least three people who died of “Influenza” in the town the same year.

To learn more about the 1918 influenza pandemic, visit the City of Greater Sudbury Archives website at www.greatersudbury.ca/archives. Click on “Search our Holdings” and follow the links to Archeion.

To listen to firsthand accounts of the 1918 flu from the radio program Memories and Music, type Jack Sauerbrei or Jim Vanderbeck in the search bar and click on the result.

(Or visit https://www.archeion.ca/jack-sauerbrei or https://www.archeion.ca/jim-vanderbeck. Jack Sauerbrei briefly shares his memories of the 1918 pandemic and Jim Vanderbeck mentions it in passing in regards to the deaths of two of his siblings.)

To learn about a First World War Soldier who died of the 1918 influenza, type Royal Canadian Legion Dr. Fred Starr Branch 76 in the search bar and click on the first result. Then click on Book of Remembrance (on the left-hand side) and then Reference Guide for the Book of Remembrance. Click on the Reference Guide and do a keyword search for Bonhomme, Edward. (Or visit https://www.archeion.ca/uploads/r/city-of-greater-sudbury-archives/0/e/a/0ead56772442d906f52f8add99986c8796da800859c8ad337733c0953ed817d4/Book_of_Remembrance_Reference_Guide_p1-15.pdf and search for Bonhomme, Edward.)

Shanna Fraser is the city archivist for the City of Greater Sudbury.

Health

Canada to donate up to 200,000 vaccine doses to combat mpox outbreaks in Africa

The Canadian government says it will donate up to 200,000 vaccine doses to fight the mpox outbreak in Congo and other African countries.

It says the donated doses of Imvamune will come from Canada’s existing supply and will not affect the country’s preparedness for mpox cases in this country.

Minister of Health Mark Holland says the donation “will help to protect those in the most affected regions of Africa and will help prevent further spread of the virus.”

Dr. Madhukar Pai, Canada research chair in epidemiology and global health, says although the donation is welcome, it is a very small portion of the estimated 10 million vaccine doses needed to control the outbreak.

Vaccine donations from wealthier countries have only recently started arriving in Africa, almost a month after the World Health Organization declared the mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern.

A few days after the declaration in August, Global Affairs Canada announced a contribution of $1 million for mpox surveillance, diagnostic tools, research and community awareness in Africa.

On Thursday, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention said mpox is still on the rise and that testing rates are “insufficient” across the continent.

Jason Kindrachuk, Canada research chair in emerging viruses at the University of Manitoba, said donating vaccines, in addition to supporting surveillance and diagnostic tests, is “massively important.”

But Kindrachuk, who has worked on the ground in Congo during the epidemic, also said that the international response to the mpox outbreak is “better late than never (but) better never late.”

“It would have been fantastic for us globally to not be in this position by having provided doses a much, much longer time prior than when we are,” he said, noting that the outbreak of clade I mpox in Congo started in early 2023.

Clade II mpox, endemic in regions of West Africa, came to the world’s attention even earlier — in 2022 — as that strain of virus spread to other countries, including Canada.

Two doses are recommended for mpox vaccination, so the donation may only benefit 100,000 people, Pai said.

Pai questioned whether Canada is contributing enough, as the federal government hasn’t said what percentage of its mpox vaccine stockpile it is donating.

“Small donations are simply not going to help end this crisis. We need to show greater solidarity and support,” he said in an email.

“That is the biggest lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic — our collective safety is tied with that of other nations.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 13, 2024.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

Health

How many Nova Scotians are on the doctor wait-list? Number hit 160,000 in June

HALIFAX – The Nova Scotia government says it could be months before it reveals how many people are on the wait-list for a family doctor.

The head of the province’s health authority told reporters Wednesday that the government won’t release updated data until the 160,000 people who were on the wait-list in June are contacted to verify whether they still need primary care.

Karen Oldfield said Nova Scotia Health is working on validating the primary care wait-list data before posting new numbers, and that work may take a matter of months. The most recent public wait-list figures are from June 1, when 160,234 people, or about 16 per cent of the population, were on it.

“It’s going to take time to make 160,000 calls,” Oldfield said. “We are not talking weeks, we are talking months.”

The interim CEO and president of Nova Scotia Health said people on the list are being asked where they live, whether they still need a family doctor, and to give an update on their health.

A spokesperson with the province’s Health Department says the government and its health authority are “working hard” to turn the wait-list registry into a useful tool, adding that the data will be shared once it is validated.

Nova Scotia’s NDP are calling on Premier Tim Houston to immediately release statistics on how many people are looking for a family doctor. On Tuesday, the NDP introduced a bill that would require the health minister to make the number public every month.

“It is unacceptable for the list to be more than three months out of date,” NDP Leader Claudia Chender said Tuesday.

Chender said releasing this data regularly is vital so Nova Scotians can track the government’s progress on its main 2021 campaign promise: fixing health care.

The number of people in need of a family doctor has more than doubled between the 2021 summer election campaign and June 2024. Since September 2021 about 300 doctors have been added to the provincial health system, the Health Department said.

“We’ll know if Tim Houston is keeping his 2021 election promise to fix health care when Nova Scotians are attached to primary care,” Chender said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 11, 2024.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

Health

Newfoundland and Labrador monitoring rise in whooping cough cases: medical officer

ST. JOHN’S, N.L. – Newfoundland and Labrador‘s chief medical officer is monitoring the rise of whooping cough infections across the province as cases of the highly contagious disease continue to grow across Canada.

Dr. Janice Fitzgerald says that so far this year, the province has recorded 230 confirmed cases of the vaccine-preventable respiratory tract infection, also known as pertussis.

Late last month, Quebec reported more than 11,000 cases during the same time period, while Ontario counted 470 cases, well above the five-year average of 98. In Quebec, the majority of patients are between the ages of 10 and 14.

Meanwhile, New Brunswick has declared a whooping cough outbreak across the province. A total of 141 cases were reported by last month, exceeding the five-year average of 34.

The disease can lead to severe complications among vulnerable populations including infants, who are at the highest risk of suffering from complications like pneumonia and seizures. Symptoms may start with a runny nose, mild fever and cough, then progress to severe coughing accompanied by a distinctive “whooping” sound during inhalation.

“The public, especially pregnant people and those in close contact with infants, are encouraged to be aware of symptoms related to pertussis and to ensure vaccinations are up to date,” Newfoundland and Labrador’s Health Department said in a statement.

Whooping cough can be treated with antibiotics, but vaccination is the most effective way to control the spread of the disease. As a result, the province has expanded immunization efforts this school year. While booster doses are already offered in Grade 9, the vaccine is now being offered to Grade 8 students as well.

Public health officials say whooping cough is a cyclical disease that increases every two to five or six years.

Meanwhile, New Brunswick’s acting chief medical officer of health expects the current case count to get worse before tapering off.

A rise in whooping cough cases has also been reported in the United States and elsewhere. The Pan American Health Organization issued an alert in July encouraging countries to ramp up their surveillance and vaccination coverage.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 10, 2024.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

-

Sports16 hours ago

Sports16 hours agoDolphins will bring in another quarterback, while Tagovailoa deals with concussion

-

Sports17 hours ago

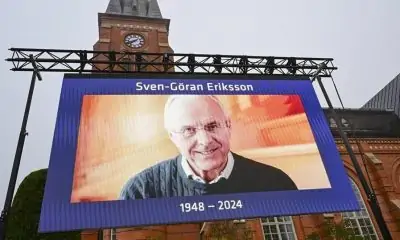

Sports17 hours agoDavid Beckham among soccer dignitaries attending ex-England coach Sven-Goran Eriksson’s funeral

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoVancouver Whitecaps cautious of lowly San Jose Earthquakes

-

Sports11 hours ago

Sports11 hours agoEdmonton Oilers sign defenceman Travis Dermott to professional tryout

-

News17 hours ago

News17 hours agoAlberta town adopts new resident code of conduct to address staff safety

-

Tech13 hours ago

Tech13 hours agoUnited Airlines will offer free internet on flights using service from Elon Musk’s SpaceX

-

Sports4 hours ago

Sports4 hours agoKirk’s walk-off single in 11th inning lifts Blue Jays past Cardinals 4-3

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoUnifor says workers at Walmart warehouse in Mississauga, Ont., vote to join union