Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu first stormed to power a quarter of a century ago and has since refashioned Israeli politics with the help of Republican strategists from the United States. In power continuously since 2009, Israel’s longest-serving leader is seeking a record sixth term in Tuesday’s election, the fourth such vote in just two years.

As Israelis voted in an election Netanyahu was tipped to lose in March 2015, the incumbent prime minister released an election day video message aimed at drumming up support among his traditionally loyal base.

“Arab voters are heading to the polling stations in droves,” Netanyahu warned, seeking to scare his religious and nationalist base into turning out en masse.

Netanyahu went on to win that election, confounding most predictions of a narrow defeat. He would repeat the stunt four years later, this time on the eve of another general election, appearing alongside then US president Donald Trump’s pollster John McLaughlin to warn of an impending “leftist” takeover.

“Mr Prime Minister, right now we are losing the race,” McLaughlin told Netanyahu in a video message designed to alarm supporters of his Likud party and its allies on the right.

Once again, the defeat that was forecast for Netanyahu failed to materialise. An April 2019 vote in which he faced off against challenger Benny Gantz and his Blue and White party instead ushered in a cycle of inconclusive elections and beleaguered attempts at a unity government, sending Israeli voters back to the polls Tuesday for the fourth time in two years.

Another referendum on ‘Bibi’

McLaughlin’s collaboration with Netanyahu, which began ahead of the 2015 vote, fits into a long history of partnerships between Republican strategists and the US-educated Israeli PM. Those ties go back to Netanyahu’s very first election win – the 1996 upset masterminded by Arthur Finkelstein, an influential conservative consultant who worked for former US presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

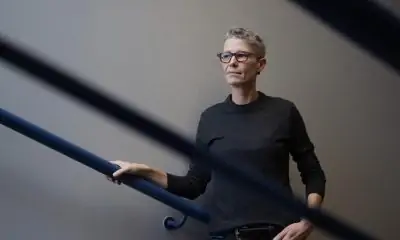

“Netanyahu proved to be a good student, learning all the best tactics from the many consultants he worked with,” says Dahlia Scheindlein, a pollster and political adviser who has worked on multiple Israeli campaigns

“He’s very skilled at dominating the media, he knows how to generate headline news,” she tells FRANCE 24.

“That’s a classic hallmark of populists – and he’s very good at it.”

Much has been said about the enduring appeal of “Bibi”, his natural charisma and his baritone voice. Over the years, none of his rivals have succeeded in matching his relentless campaigning or his ability to absorb the media’s attention.

While campaign issues and alliances have shifted during the country’s recent two-year political morass, Tuesday’s contest is again being framed as a referendum on Netanyahu – a narrative that has dominated recent elections and underscores the extent to which Israel’s longest-serving prime minister has personalised the country’s politics.

“It’s a referendum [on Netanyahu’s leadership] because he’s the reason we’re having this election in the first place,” says Scheindlein, referring to the prime minister’s decision to engineer the collapse of the power-sharing deal he agreed last year with centrist rival Gantz.

“It’s also seen as a referendum because Netanyahu has become a symbol of the many burning issues dividing Israel today,” she says – from the steady religious encroachment on public life, advocated by his ultra-Orthodox allies, to his own assaults on the independence of the judiciary.

Bannon’s protégé

But this time Israel’s five-term prime minister, who has been in power since 2009, is running for re-election while also standing trial on corruption charges. Critics say his main aim is to secure enough support in parliament to ensure MPs grant him immunity from prosecution. His still loyal supporters, however, say the charges levelled at “King Bibi” are politically motivated.

[embedded content]

While Gantz is now largely sidelined, Netanyahu faces stiff opposition from rival nationalist parties. He is stumping on the success of the country’s Covid-19 vaccination campaign and the normalisation deals with four Arab states orchestrated by the Trump administration.

The former US president, with whom Netanyahu had forged a close bond, has been conspicuously absent from the latest campaign. Gone are the giant billboards on highways and high-rises showing the two men together, a fixture of Israel’s most recent elections. But Trump’s legacy continues to shape Israeli politics, particularly in the prime minister’s camp.

Last year, Netanyahu hired and soon fired two former Trump campaign aides, Corey Lewandowski and David Bossie, who had been brought in to advise the Likud campaign. He also tapped Aaron Klein, a protégé of Trump’s former chief strategist Steve Bannon who rapidly became an influential member of the prime minister’s inner circle and whom some Israeli media dubbed “the Bibi whisperer” .

A former Jerusalem bureau chief for Bannon’s alt-right media outlet Breitbart, Klein has co-authored several books about former US president Barack Obama, including “The Manchurian President: Barack Obama’s Ties to Communists, Socialists and Other Anti-American Extremists”. Following Trump’s election in 2016, Bannon credited Klein with hatching a plan to destabilise Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton during a presidential debate by inviting women who had accused her husband – former president Bill Clinton – of sexual assault.

In November 2019, as Netanyahu’s legal troubles worsened, Axios news site said Klein had volunteered to help the prime minister fight his corruption indictments. Months later, Netanyahu publicly thanked Klein, then his chief strategist, for his “clever” advice ahead of Israel’s 2020 election. He promoted him to campaign manager for the 2021 vote.

Battle of the US consultants

Netanyahu is not the only Israeli politician to have tapped US strategists. One of his main rivals on the right, former Likud heavyweight Gideon Saar, briefly recruited consultants from the Lincoln Group of anti-Trump Republicans – in what some described as an Israeli extension of the rivalry inside the GOP.

Another key challenger from the right, Naftali Bennett, has hired Netanyahu’s former chief of staff George Birnbaum, while a Democratic strategist is advising the main centrist candidate, Yair Lapid.

“The battle of the American consultants has been going on for a long time,” says Scheindlein, who was part of the team of Democrats that helped counter Finkelstein in Israel’s acrimonious 1999 election, in which Labor’s Ehud Barak defeated Netanyahu.

More than two decades later, Scheindlein argues that negative campaigning and demonisation of the left are still hallmarks of Netanyahu’s election tactics.

“This time he’s making Yair Lapid into the big enemy, branding him a leftist. But he’s done much more negative campaigning in the past, such as linking the left to ISIS (the Islamic State group) in 2015,” she says. “Negative campaigning is part of who he is.”

Enter ‘Abu Yair’

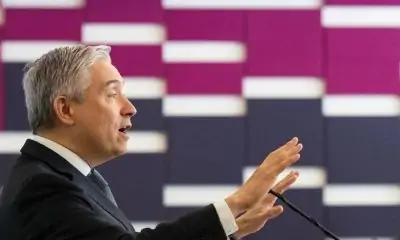

Gideon Rahat, a professor of political science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a member of the Israel Democracy Institute, sees negative campaigning and personality politics as two things that are “very American” that Netanyahu has helped introduce into Israel’s multi-party, parliamentary system.

However, he notes that an increasingly fragmented political landscape and the rise of challengers on Netanyahu’s right have made it very difficult for the prime minister to use the kind of tactics he deployed against Gantz.

“It’s very easy to target one opponent but very hard to use the same strategy when under attack from the centre and the right,” Rahat explains in an interview with FRANCE 24.

Rahat says Netanyahu’s attempts to cling on to power and stave off prosecution at the same time have pushed him further into Trump-style populist terrain, “first targeting the media, then prosecutors, then the courts”. He has also been forced to seek out new supporters in the most unlikely places.

[embedded content]

Six years after his infamous comments on Arabs voting “in droves”, Netanyahu has made an unprecedented push to woo Arab Israelis, campaigning in areas he used to shun and embracing the nickname “Abu Yair” (father of Yair), following the Arab custom of referring to parents as the father or mother of their eldest son.

Arabs count for just over a fifth of the Israeli population, a marginalised constituency that could help break the country’s protracted political deadlock. Just 2 percent voted for Netanyahu’s Likud at the last election. But should he succeed in winning over a larger share – even as he cultivates far-right parties that advocate the expulsion of Arabs – it would certainly buttress his reputation as the magician and master manipulator of Israeli politics.

“He can wear a galabiya (tunic) and call himself Abu Yair from now until the election,” Ahmed Tibi, a leader of the Joint List coalition of Israel’s Arab parties, told The Economist last week.

“Whoever believes him, deserves him.”