Economy

Here’s what’s really hurting the economy

|

|

I went out for pizza the other night, but had to eat it in my car.

That’s because the Frank Pepe’s in Manchester, Connecticut had this sign on its door.

“Attention: Dining Room closed after 4 p.m. today due to staffing shortages.”

So I ate in my SUV, no problem, (the pizza was fantastic), but it made me think 1) this can’t be good for Frank Pepe’s, and 2) the note on the door is literally a sign of the times.

A sign we’re living in a world where supply shortages — employees, oil, semiconductors — are commonplace and impacting the economy to a degree we haven’t seen for decades. The implications on inflation, Fed policy, a possible recession and our global well-being are immeasurable.

Supply constraints are everywhere these days, some Captain Obvious, others more opaque. In some instances economic downturns are caused by drops in demand. That might be the result of a stock market crash like after 1987 or 2000, as consumers have less money to spend. Or it could be an event like the February to April 2020 COVID recession, when people didn’t venture out to buy things.

Supply shocks can cause downturns or recessions, too. “In the 1970s, there were two mega supply shocks,” economist Nouriel Roubini told me during the recent Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit. “One was the war between Israel and the Arab states which led to a spike in oil prices in ’73 and the second one was the [1979 Iranian revolution] which also caused a spike of oil prices. This time around, the spike is not just in an oil crisis, it is natural gas, food, fertilizer, industrial products, and semiconductors.”

Since the onset of COVID, the global economy has been battered by both supply and demand shocks, which have vexed leaders around the globe. The roughly $5 trillion of stimulus our government put into the economy jacked up demand for cars, homes and meme stocks, etc. Given those aforementioned supply constraints, it’s hard to recall a time with such pronounced supply-demand mismatches.

One effect has been inflation, currently running at 8.2% — still hovering near the 40-year high of 9.1% we saw in June. Can we discern how much of that comes from the demand side, how much from supply? Phil Levy, chief economist at Flexport, says that while Europe’s energy problems suggest a supply shock, too much demand is the bigger problem.

“The largest part of what we’re seeing with [higher] prices is coming from demand, which has increased — and supply can’t quite keep up with the pace,” Levy says.

The causes of supply deficiencies

Let’s drill down into those supply deficiencies, the causes of which include the pandemic, the great resignation, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, de-globalization and climate change — or some combination of these factors.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted supplies of wheat, corn and grain and even sunflower seeds. His stranglehold over Europe’s natural gas supply, plus the sabotage of a pipeline there, plus boycotts of Russian oil and gas means less energy for Europe and beyond. There are already slowdowns and stoppages of manufacturing. Winter is only 60 days away, and rationing for heat is a distinct possibility.

This is a global supply problem. How about this recent headline from the Wall Street Journal: “New England Risks Winter Blackouts as Gas Supplies Tighten Grid officials warn of strain as the region competes with European countries for shipments of liquefied natural gas.”

Speaking of New England, climate change can wreak havoc on supply, as you may find out this Thanksgiving when your cranberry sauce is prohibitively expensive or even non-existent due to shortages. Why? Extreme drought in New England, which Zachary Zobel, a scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts, told Grist was the result of climate change. Climate change is disrupting the supply chain in many other ways, and on a much bigger scale.

The chip shortage has also been hitting industries across the globe — including the auto business, as GM CEO Mary Barra recently told me. But it’s not just the huge corporations being hit by low chip supplies. My alma mater, Bowdoin College, recently ran into supply-chain snags while trying to complete some buildings.

“Due to chip shortages, the companies that manufacture the controls for our AV systems have announced 12-24 month shipping delays, and we are being warned that networking equipment will be similarly challenged,” Michael Cato, Chief Information Officer. “This complicates our planning in multiple ways including timing for financial budgets and navigating the multi-year timeline of construction projects.”

There might also be a shortage of workers to complete those projects. The great resignation has hit many businesses, but it’s also affecting the government. John McQuillan, CEO of Triumvirate Environmental, which disposes commercial and hazardous waste, has a business that requires government permitting — a process he says has slowed.

“We want to increase our processing capacity, but you have a bunch of regulators who have resigned. The more experienced people tend to be older. I have four or five things pending in the United States, Canada and Mexico right now. And in all of the instances I hear is, ‘We have staffing shortages, the key person has retired, or we’re waiting to hire somebody for that position.’”

What do we have in our anti-inflation toolkit?

What can be done about supply issues? Remembering, they are a significant cause of inflation and possibly a recession. Ideally, the Federal Reserve can moderate inflation by raising interest rates. Unfortunately, the Fed’s traditional tools, raising interest rates and shrinking its balance sheet, are about curbing demand, not increasing supply. That doesn’t mean that policymakers and the private sector are helpless.

Michael Spence, a Nobel laureate in economics and professor emeritus at Stanford, writes in Project Syndicate that higher rates and withdrawing liquidity “threaten to push global growth below potential.” “There is another way,” he says, “supply-side measures.” Like what? Spence argues that “creeping protectionism must be reversed,” and urges a removal of tariffs. He also says that efforts must be made to improve productivity. “Many sectors — including the public sector — are lagging, and concerns about the effects of automation on employment persist.”

In a recent report by the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in Washington, chief economist Marc Jarsulic argues for expanding the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines to reduce labor and manufacturing supply shocks, providing additional support for child and home care to raise labor force participation and reducing limits on working-age immigration to increase labor supply.

“Actions such as these are not part of the standard anti-inflation toolkit, but given the changing economic environment, they ought to be,” Jarsulic says.

In fact all these supply issues may produce a silver lining, argues Financial Times columnist Rana Foroohar in her new book “Homecoming, The Path to Prosperity in a Post-Global World,” who notes: “The supply chain disruptions of the last few years have now lasted longer than the 1973–74 and 1979 oil embargoes combined. This isn’t a blip but rather the new normal.”

The book argues that “a new age of economic localization will reunite place and prosperity. Place-based economics and a wave of technological innovations now make it possible to keep operations, investment, and wealth closer to home, wherever that may be.”

Here’s hoping Foroohar has written the silver lining playbook.

This article was featured in a Saturday edition of the Morning Brief on Oct. 22. Get the Morning Brief sent directly to your inbox every Monday to Friday by 6:30 a.m. ET. Subscribe

Follow Andy Serwer, editor-in-chief of Yahoo Finance, on Twitter: @serwer

Economy

Opinion: Higher capital gains taxes won't work as claimed, but will harm the economy – The Globe and Mail

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland hold the 2024-25 budget, on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, on April 16.Patrick Doyle/Reuters

Alex Whalen and Jake Fuss are analysts at the Fraser Institute.

Amid a federal budget riddled with red ink and tax hikes, the Trudeau government has increased capital gains taxes. The move will be disastrous for Canada’s growth prospects and its already-lagging investment climate, and to make matters worse, research suggests it won’t work as planned.

Currently, individuals and businesses who sell a capital asset in Canada incur capital gains taxes at a 50-per-cent inclusion rate, which means that 50 per cent of the gain in the asset’s value is subject to taxation at the individual or business’s marginal tax rate. The Trudeau government is raising this inclusion rate to 66.6 per cent for all businesses, trusts and individuals with capital gains over $250,000.

The problems with hiking capital gains taxes are numerous.

First, capital gains are taxed on a “realization” basis, which means the investor does not incur capital gains taxes until the asset is sold. According to empirical evidence, this creates a “lock-in” effect where investors have an incentive to keep their capital invested in a particular asset when they might otherwise sell.

For example, investors may delay selling capital assets because they anticipate a change in government and a reversal back to the previous inclusion rate. This means the Trudeau government is likely overestimating the potential revenue gains from its capital gains tax hike, given that individual investors will adjust the timing of their asset sales in response to the tax hike.

Second, the lock-in effect creates a drag on economic growth as it incentivizes investors to hold off selling their assets when they otherwise might, preventing capital from being deployed to its most productive use and therefore reducing growth.

Budget’s capital gains tax changes divide the small business community

And Canada’s growth prospects and investment climate have both been in decline. Canada currently faces the lowest growth prospects among all OECD countries in terms of GDP per person. Further, between 2014 and 2021, business investment (adjusted for inflation) in Canada declined by $43.7-billion. Hiking taxes on capital will make both pressing issues worse.

Contrary to the government’s framing – that this move only affects the wealthy – lagging business investment and slow growth affect all Canadians through lower incomes and living standards. Capital taxes are among the most economically damaging forms of taxation precisely because they reduce the incentive to innovate and invest. And while taxes on capital gains do raise revenue, the economic costs exceed the amount of tax collected.

Previous governments in Canada understood these facts. In the 2000 federal budget, then-finance minister Paul Martin said a “key factor contributing to the difficulty of raising capital by new startups is the fact that individuals who sell existing investments and reinvest in others must pay tax on any realized capital gains,” an explicit acknowledgment of the lock-in effect and costs of capital gains taxes. Further, that Liberal government reduced the capital gains inclusion rate, acknowledging the importance of a strong investment climate.

At a time when Canada badly needs to improve the incentives to invest, the Trudeau government’s 2024 budget has introduced a damaging tax hike. In delivering the budget, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said “Canada, a growing country, needs to make investments in our country and in Canadians right now.” Individuals and businesses across the country likely agree on the importance of investment. Hiking capital gains taxes will achieve the exact opposite effect.

Economy

Nigeria's Economy, Once Africa's Biggest, Slips to Fourth Place – Bloomberg

Nigeria’s economy, which ranked as Africa’s largest in 2022, is set to slip to fourth place this year and Egypt, which held the top position in 2023, is projected to fall to second behind South Africa after a series of currency devaluations, International Monetary Fund forecasts show.

The IMF’s World Economic Outlook estimates Nigeria’s gross domestic product at $253 billion based on current prices this year, lagging energy-rich Algeria at $267 billion, Egypt at $348 billion and South Africa at $373 billion.

Economy

IMF Sees OPEC+ Oil Output Lift From July in Saudi Economic Boost – BNN Bloomberg

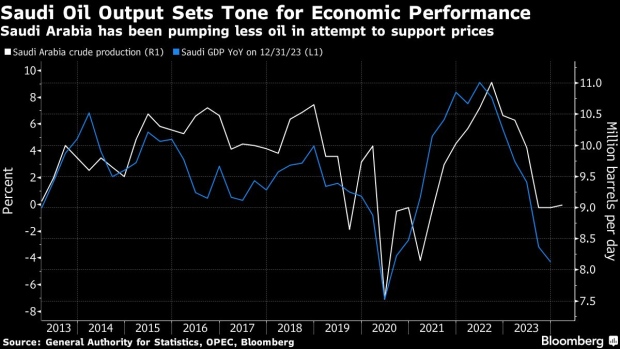

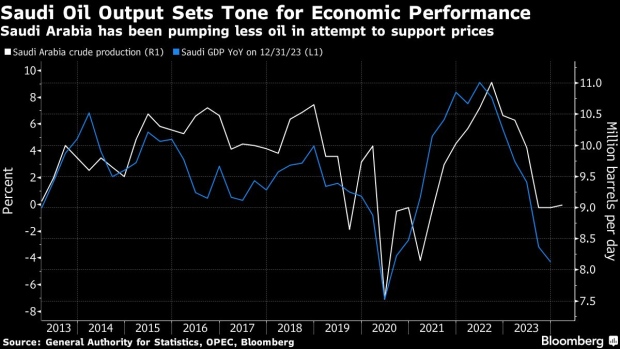

(Bloomberg) — The International Monetary Fund expects OPEC and its partners to start increasing oil output gradually from July, a transition that’s set to catapult Saudi Arabia back into the ranks of the world’s fastest-growing economies next year.

“We are assuming the full reversal of cuts is happening at the beginning of 2025,” Amine Mati, the lender’s mission chief to the kingdom, said in an interview in Washington, where the IMF and the World Bank are holding their spring meetings.

The view explains why the IMF is turning more upbeat on Saudi Arabia, whose economy contracted last year as it led the OPEC+ alliance alongside Russia in production cuts that squeezed supplies and pushed up crude prices. In 2022, record crude output propelled Saudi Arabia to the fastest expansion in the Group of 20.

Under the latest outlook unveiled this week, the IMF improved next year’s growth estimate for the world’s biggest crude exporter from 5.5% to 6% — second only to India among major economies in an upswing that would be among the kingdom’s fastest spurts over the past decade.

The fund projects Saudi oil output will reach 10 million barrels per day in early 2025, from what’s now a near three-year low of 9 million barrels. Saudi Arabia says its production capacity is around 12 million barrels a day and it’s rarely pumped as low as today’s levels in the past decade.

Mati said the IMF slightly lowered its forecast for Saudi economic growth this year to 2.6% from 2.7% based on actual figures for 2023 and the extension of production curbs to June. Bloomberg Economics predicts an expansion of 1.1% in 2024 and assumes the output cuts will stay until the end of this year.

Worsening hostilities in the Middle East provide the backdrop to a possible policy shift after oil prices topped $90 a barrel for the first time in months. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies will gather on June 1 and some analysts expect the group may start to unwind the curbs.

After sacrificing sales volumes to support the oil market, Saudi Arabia may instead opt to pump more as it faces years of fiscal deficits and with crude prices still below what it needs to balance the budget.

Saudi Arabia is spending hundreds of billions of dollars to diversify an economy that still relies on oil and its close derivatives — petrochemicals and plastics — for more than 90% of its exports.

Restrictive US monetary policy won’t necessarily be a drag on Saudi Arabia, which usually moves in lockstep with the Federal Reserve to protect its currency peg to the dollar.

Mati sees a “negligible” impact from potentially slower interest-rate cuts by the Fed, given the structure of the Saudi banks’ balance sheets and the plentiful liquidity in the kingdom thanks to elevated oil prices.

The IMF also expects the “non-oil sector growth momentum to remain strong” for at least the next couple of years, Mati said, driven by the kingdom’s plans to develop industries from manufacturing to logistics.

The kingdom “has undertaken many transformative reforms and is doing a lot of the right actions in terms of the regulatory environment,” Mati said. “But I think it takes time for some of those reforms to materialize.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

-

Investment24 hours ago

Investment24 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Media3 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Business21 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Media5 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Art20 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

-

Investment21 hours ago

Investment21 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Tech23 hours ago

Tech23 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET