Health

How Scientists Are Working 24/7 Looking For Old Drugs That Might Treat COVID-19 – ScienceAlert

Why don’t we have drugs to treat COVID-19 and how long will it take to develop them? SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes the disease COVID-19 – is completely new and attacks cells in a novel way. Every virus is different and so are the drugs used to treat them.

That’s why there wasn’t a drug ready to tackle the new coronavirus that only emerged a few months ago.

As a systems biologist who studies how cells are affected by viruses during infections, I’m especially interested in the second question. Finding points of vulnerability and developing a drug to treat a disease typically takes years.

But the new coronavirus isn’t giving the world that kind of time. With most of the world on lockdown and the looming threat of millions of deaths, researchers need to find an effective drug much faster.

This situation has presented my colleagues and me with the challenge and opportunity of a lifetime: to help solve this huge public health and economic crisis posed by the global pandemic of SARS-CoV-2.

Facing this crisis, we assembled a team here at the Quantitative Biosciences Institute (QBI) at the University of California, San Francisco, to discover how the virus attacks cells.

But instead of trying to create a new drug based on this information, we are first looking to see if there are any drugs available today that can disrupt these pathways and fight the coronavirus.

The team of 22 labs, that we named the QCRG, is working at breakneck speed – literally around the clock and in shifts – seven days a week. I imagine this is what it felt like to be in wartime efforts like the Enigma code-breaking group during World War II, and our team is similarly hoping to disarm our enemy by understanding its inner workings.

A stealthy opponent

Compared with human cells, viruses are small and can’t reproduce on their own. The coronavirus has about 30 proteins, whereas a human cell has more than 20,000.

To get around this limited set of tools, the virus cleverly turns the human body against itself. The pathways into a human cell are normally locked to outside invaders, but the coronavirus uses its own proteins like keys to open these “locks” and enter a person’s cells.

Once inside, the virus binds to proteins the cell normally uses for its own functions, essentially hijacking the cell and turning it into a coronavirus factory. As the resources and mechanics of infected cells get retooled to produce thousands and thousands of viruses, the cells start dying.

Lung cells are particularly vulnerable to this because they express high amounts of the “lock” protein SARS-CoV-2 uses for entry. A large number of a person’s lung cells dying causes the respiratory symptoms associated with COVID-19.

There are two ways to fight back. First, drugs could attack the virus’s own proteins, preventing them from doing jobs like entering the cell or copying their genetic material once they are inside. This is how remdesivir – a drug currently in clinical trials for COVID-19 – works.

A problem with this approach is that viruses mutate and change over time. In the future, the coronavirus could evolve in ways that render a drug like remdesivir useless. This arms race between drugs and viruses is why you need a new flu shot every year.

Alternatively, a drug can work by blocking a viral protein from interacting with a human protein it needs. This approach – essentially protecting the host machinery – has a big advantage over disabling the virus itself, because the human cell doesn’t change as fast.

Once you find a good drug, it should keep working. This is the approach that our team is taking. And it may also work against other emergent viruses.

Learning the enemy’s plans

The first thing our group needed to do was identify every part of the cellular factory that the coronavirus relies on to reproduce. We needed to find out what proteins the virus was hijacking.

To do this, a team in my lab went on a molecular fishing expedition inside human cells. Instead of a worm on a hook, they used viral proteins with tiny chemical tags attached to them – termed a “bait.”

We put these baits into lab-grown human cells and then pulled them out to see what we caught. Anything that stuck was a human protein that the virus hijacks during infection.

By March 2, we had a partial list of the human proteins that the coronavirus needs to thrive. These were the first clues we could use. A team member sent a message to our group, “First iteration, just 3 baits … next 5 baits coming.” The fight was on.

Counterattack

Once we had this list of molecular targets the virus needs to survive, members of the team raced to identify known compounds that might bind to these targets and prevent the virus from using them to replicate.

If a compound can prevent the virus from copying itself in a person’s body, the infection stops. But you can’t simply interfere with cellular processes at will without potentially causing harm to the body.

Our team needed to be sure the compounds we identified would be safe and nontoxic for people.

The traditional way to do this would involve years of pre-clinical studies and clinical trials costing millions of dollars. But there is a fast and basically free way around this: looking to the 20,000 FDA-approved drugs that have already been safety-tested. Maybe there is a drug in this large list that can fight the coronavirus.

Our chemists used a massive database to match the approved drugs and proteins they interact with to the proteins on our list. They found 10 candidate drugs last week.

For example, one of the hits was a cancer drug called JQ1. While we cannot predict how this drug might affect the virus, it has a good chance of doing something. Through testing, we will know if that something helps patients.

Facing the threat of global border shutdowns, we immediately shipped boxes of these 10 drugs to three of the few labs in the world working with live coronavirus samples: two at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and Mount Sinai in New York.

By March 13, the drugs were being tested in cells to see if they prevent the virus from reproducing.

Dispatches from the battlefield

Our team will soon learn from our collaborators at Mt. Sinai and the Pasteur Institute whether any of these first 10 drugs work against SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Meanwhile, the team has continued fishing with viral baits, finding hundreds of additional human proteins that the coronavirus co-opts. We will be publishing the results in the online repository BioRxiv soon.

The good news is that so far, our team has found 50 existing drugs that bind the human proteins we’ve identified. This large number makes me hopeful that we’ll be able to find a drug to treat COVID-19.

If we find an approved drug that even slows down the virus’s progression, doctors should be able to start getting it to patients quickly and save lives.

Nevan Krogan, Professor and Director of Quantitative Biosciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Health

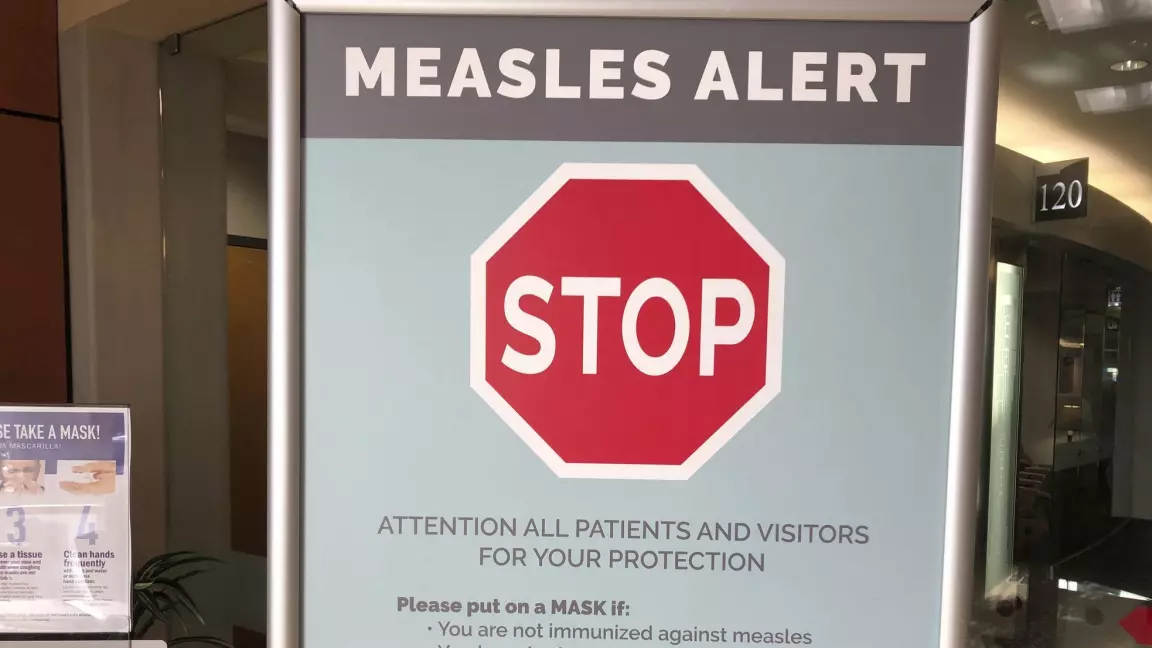

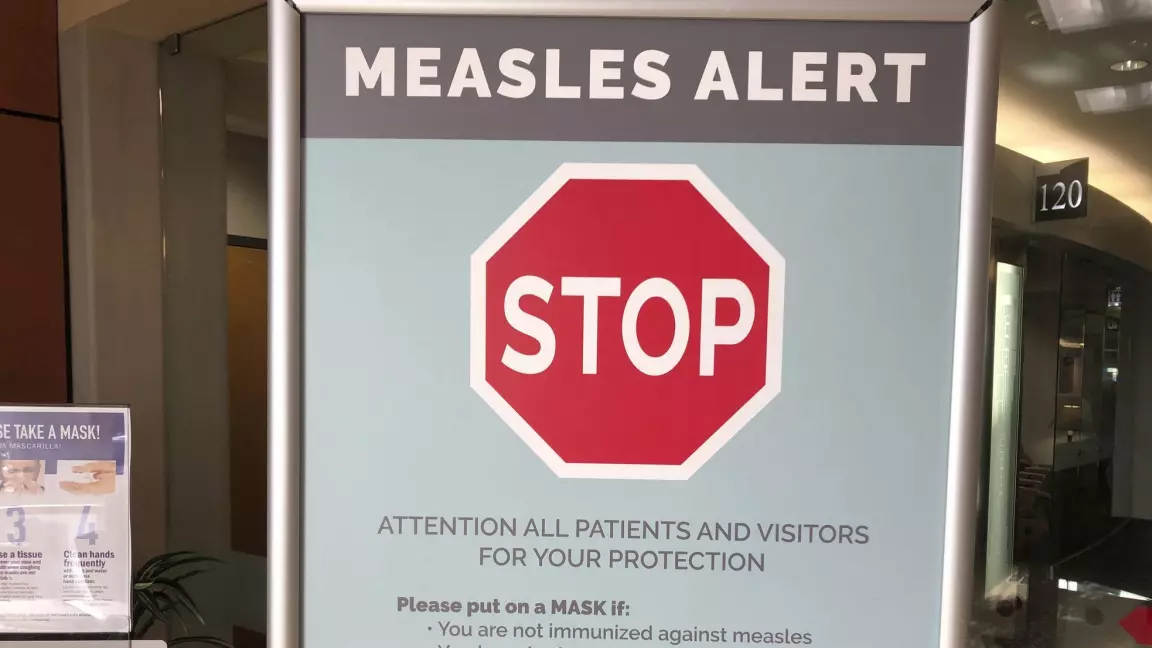

Quebec successfully pushes back against rise in measles cases – CBC.ca

Quebec appears to be winning its battle against the rising tide of measles after 45 cases were confirmed province-wide this year.

“We’ve had no locally transmitted measles cases since March 25, so that’s good news,” said Dr. Paul Le Guerrier, responsible for immunization for Montreal Public Health.

There are 17 patients with measles in Quebec currently, and the most recent case is somebody who was infected while abroad, he said.

But it was no small task to get to this point.

Le Guerrier said once local transmission was detected, news was spread fast among health centres to ensure proper protocols were followed — such as not letting potentially infected people sit in waiting rooms for hours on end.

Then about 90 staffers were put to work, tracking down those who were in contact with positive cases and are not properly vaccinated. They were given post-exposure prophylaxis, which prevents disease, said Le Guerrier.

From there, a vaccination campaign was launched, especially in daycares, schools and neighbourhoods with low inoculation rates. There was an effort to convince parents to get their children vaccinated.

Vaccination in schools boosted

Some schools, mostly in Montreal, had vaccination rates as low as 30 or 40 per cent.

“Vaccination was well accepted and parents responded well,” said Le Guerrier. “Some schools went from very low to as high as 85 to 90 per cent vaccination coverage.”

But it’s not only children who aren’t properly vaccinated. Le Guerrier said people need two doses after age one to be fully inoculated, and he encouraged people to check their status.

There are all kinds of reasons why people aren’t vaccinated, but it’s only about five per cent who are against immunization, he said. So far, some 10,000 people have been vaccinated against measles province-wide during this campaign, Le Guerrier said.

The next step is to continue pushing for further vaccination, but he said, small outbreaks are likely in the future as measles is spreading abroad and travellers are likely to bring it back with them.

Need to improve vaccination rate, expert says

Dr. Donald Vinh, an infectious diseases specialist from the McGill University Health Centre, said it’s not time to rest on our laurels, but this is a good indication that public health is able to take action quickly and that people are willing to listen to health recommendations.

“We are not seeing new cases or at least the new cases are not exceeding the number of cases that we can handle,” said Vinh.

“So these are all reassuring signs, but I don’t think it’s a sign that we need to become complacent.”

Vinh said there are also signs that the public is lagging in vaccine coverage and it’s important to respond to this with improved education and access. Otherwise, microbes capitalize on our weaknesses, he said.

Getting vaccination coverage up to an adequate level is necessary, Vinh said, or more small outbreaks like this will continue to happen.

“And it’s very possible that we may not be able to get one under control if we don’t react quickly enough,” he said.

Health

Pregnant women in the Black Country urged to get whooping cough vaccine – BBC.com

Pregnant women urged to get whooping cough vaccine

Pregnant women in the Black Country are being urged to get vaccinated against whooping cough after a rise in cases.

The bacterial infection of the lungs spreads very easily and can cause serious problems, especially in babies and young children.

The Black Country Integrated Care Board (ICB) is advising pregnant women between 16 and 32 weeks to contact their GP to get the vaccine so their baby has protection from birth.

The UK Health Security Agency warned earlier this year of a steady decline in uptake of the vaccine in pregnant women and children.

Symptoms of the infection, also known as “100-day cough”, are similar to a cold, with a runny nose and sore throat.

Sally Roberts, chief nursing officer for the ICB, which covers Wolverhampton, Dudley, Walsall and Sandwell, said anyone could catch it, but it was more serious for young children and babies.

“Getting vaccinated while you’re pregnant is highly effective in protecting your baby from developing whooping cough in the first few weeks of their life – ideally from 16 weeks up to 32 weeks of pregnancy,” she said.

“If for any reason you miss having the vaccine, you can still have it up until you go into labour.”

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk

Health

Measles cases stabilize in Montreal – CityNews Montreal

The number of measles cases has stabilized, according to the Montreal Public Health.

Since March 25, there have been no contaminations reported within the community.

“Our teams have identified all contact cases of measles,” said media relations advisor Geneviève Paradis. “It’s a laborious task: each measles case produces hundreds of contacts.”

All community transmission cases since February 2024 have been caused by returning travelers who were either unvaccinated or partially vaccinated.

Currently, there are 18 measles cases in Montreal – with 46 total in Quebec. This according to the April 18 figures from the provincial government.

“With the summer vacations approaching, if you’re travelling, it is essential to check if you are protected against measles,” explained Paradis.

According to Montreal Public Health, a person needs to have received two doses after the age of 12 months to be immunized against the virus.

They’ve launched a vaccination campaign throughout the region, and currently, 11,341 people have been vaccinated against measles in Montreal between March 19 and April 15.

Vaccination is also being provided in schools and at local service points.

“The vaccination operation is under the responsibility of the five CIUSSS of the territory,” concluded Paradis.

-

Science6 hours ago

Science6 hours agoJeremy Hansen – The Canadian Encyclopedia

-

Tech24 hours ago

Tech24 hours agoCytiva Showcases Single-Use Mixing System at INTERPHEX 2024 – BioPharm International

-

Health20 hours ago

Health20 hours agoSupervised consumption sites urgently needed, says study – Sudbury.com

-

Investment6 hours ago

Investment6 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

News20 hours ago

Canada's 2024 budget announces 'halal mortgages'. Here's what to know – National Post

-

Tech6 hours ago

Tech6 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET

-

News19 hours ago

2024 federal budget's key takeaways: Housing and carbon rebates, students and sin taxes – CBC News

-

Science19 hours ago

Science19 hours agoGiant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found – Livescience.com