Media

India enjoyed a free and vibrant media. Narendra Modi’s brazen attacks are a catastrophe

In January, the BBC broadcast a two-part series, India: The Modi Question, which looked forensically at the role of Narendra Modi in fomenting the Gujarat anti-Muslim riots of 2002 in which at least 1,000 people were killed. Now the prime minister of India, Modi was then the chief minister of Gujarat.

The response in India was swift. Kanchan Gupta, an adviser to the ministry of information and broadcasting, called the documentary “propaganda and anti-India garbage” that “reflects BBC’s colonial mindset”. The BJP government invoked emergency laws to ban the documentary and any online links to clips. When students at the Jawaharlal Nehru University tried to screen the documentary, the university authorities cut off electricity to the whole campus.

Then, last week, the authorities raided BBC offices in India, supposedly to investigate “tax evasion” by the corporation’s Indian operation. On Friday, the government claimed to have discovered “evidence of tax irregularities”. Most local journalists are deeply cynical. The raid on the BBC, the Press Club of India observed, was “a clear cut case of vendetta”.

The cynicism about Delhi’s motives is well earned. Since Modi and his Hindu nationalist BJP party came to power in 2014, he has pursued a relentless campaign to curb the independence of India’s media. “Criticise us and we’ll come after you,” is the banner under which the government operates. As the Editors Guild of India put it, the BBC raids (which the government, in BJP Newspeak, calls not “raids” but “surveys”) are part of a well-established “trend of using government agencies to intimidate and harass press organisations that are critical of government policies or the ruling establishment”. The government – and many BJP-controlled state administrations – have also sought to intimidate journalists through the use of sedition and national security laws. In 2020, Siddique Kappan, a journalist from Kerala, reporting a story of a 19-year-old Dalit woman who died after being allegedly gang-raped by four men, was charged by police in BJP-controlled Uttar Pradesh with sedition, promoting enmity between groups, outraging religious feelings, committing unlawful activities and money laundering. Still awaiting trial, he was finally released on bail this month after two years in jail.

That same year, Dhaval Patel, editor of a Gujarati news website, was charged with sedition for writing an article critical of the state government’s Covid policy. In 2021, the journalist Kishorechandra Wangkhem was charged under the National Security Act by the BJP-led Manipur government for writing that cow dung does not cure Covid; he spent nearly two months in jail before being released by the courts.

India’s ministry of information and broadcasting blocked the television channel Media One for 48 hours because it had covered mob attacks on Muslims in Delhi in 2020 “in a way that seemed critical toward Delhi police and RSS”. The RSS is a paramilitary Hindu-nationalist movement with close ties to Modi and the BJP.

In 2021, as Delhi was rocked by huge farmers’ protests against new agricultural laws, prominent journalists, including Siddharth Varadarajan, editor of the digital website The Wire, and Vinod Jose, Anant Nath and Paresh Nath, editors and publishers of Caravan magazine, were charged with sedition for reporting on the death of one of the protesters. As Hartosh Singh Bal, Caravan’s political editor, observed, the targets were not surprising: the farmers’ protest was the biggest challenge to the BJP since it came to power, while The Wire and Caravan are “among the few media organisations willing to look at the ruling government critically”.

These are just a handful of the cases that Indian journalists have faced in recent years. Charging someone with sedition has become the weapon of choice, especially for BJP politicians and administrations when faced with criticism.

Journalists, especially female journalists, and those critical of Hindu nationalism, have not just been censored, they have been assaulted, even killed. Journalists like Gauri Lankesh, shot dead by three assailants in Bangalore in 2017. In 2021, Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) named India as one of the five most dangerous countries for a journalist.

Many media bosses have been only too happy to comply with government strictures. In 2020, during the Covid pandemic, hours before he announced the world’s largest coronavirus lockdown, Modi met senior news executives and urged them to publish only “inspiring and positive stories” about the government’s efforts. As Caravan noted, Modi’s intervention ensured little critical coverage of the government’s Covid failures. The supreme court, however, denied the government’s request for prior censorship of news stories, ordering the media to “publish the official version” of pandemic developments. Unsurprisingly, India has plummeted in the global press freedom rankings compiled by RSF. In 2002, India stood 80th in the world. Today it stands at 150th out of 180 countries, below nations such as Turkey, Libya and Zimbabwe.

Repressive censorship did not originate with the BJP. India has long had a vibrant media culture; it has also long had a culture of censorship and repression. The most despotic moment came with the imposition of the Emergency between 1975-77, when prime minister Indira Gandhi cancelled elections, suspended civil liberties, rounded up political opponents and muzzled the media. She expelled the BBC from India after it refused to sign a censorship agreement.

Nevertheless, the BJP under Modi has helped remake the relationship between the media and the state, and, outside of the Emergency, has imposed the tightest leash on the press.

While many media owners and big-name editors have toed the government line, smaller fiercely independent outlets and individual journalists have pushed back against the climate of censorship and borne the brunt of the repression. What many now fear is that the geopolitical importance of India, especially as a counterweight to China, is muting the western response, particularly after the assault on the BBC. While western governments lecturing other nations about freedom and liberty is often an unedifying sight, many fear the silence of London and Washington “could pave the way for more ‘brazen’ action… by the Modi government”.

As rightwing populists do in many other nations, the BJP presents its battering of the media as a challenge to the “elite”. It is, in reality, an attack on any criticism of the elite. The slow strangulation of a free and independent media is a catastrophe for India. But not just for India. It is a development that should trouble all of us.

Kenan Malik is an Observer columnist

Media

Mélanie Maynard Hosts Sophie Bourgeois on Sucré Salé: A Heartfelt Conversation

Media

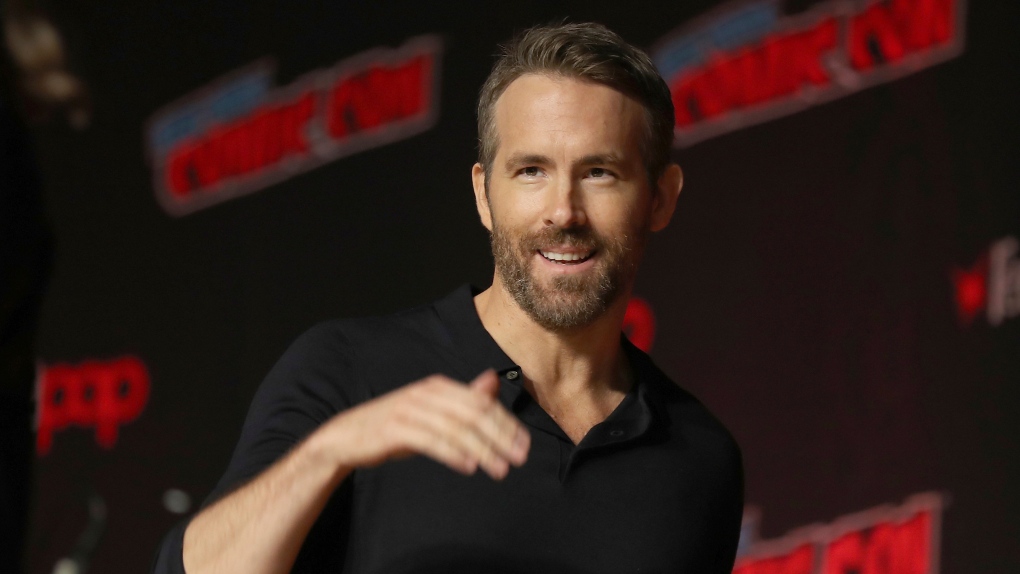

Ryan Reynolds Jokes About Taylor Swift’s Astronomical Babysitting Rates

Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively are a Hollywood power couple with four adorable children. But juggling busy careers and a growing family can be a challenge, even for A-listers. Enter their close friend, pop icon Taylor Swift, who, according to Reynolds, might be their go-to babysitter. However, her services come with a hefty price tag (at least according to Reynolds‘ playful exaggeration).

During a recent E! News interview promoting their upcoming movie “Deadpool & Wolverine,” Hugh Jackman playfully suggested that Swift was the real nanny for Reynolds and Lively’s four children. This lighthearted jab sparked a humorous response from Reynolds.

Known for his sharp wit, Reynolds responded to Jackman’s comment with a hilarious quip. He stated that the cost of having Taylor Swift babysit would be “cost-prohibitive,” implying that her rates would be astronomically high. He even playfully added, “But I think what he meant was, ‘Cost-insane-what-are-you-doing-I’m-no-longer-you’re-accountant.'”

Reynolds and Lively, who tied the knot in 2012, share four children: James (9), Inez (7), Betty (4), and a one-year-old whose name and gender remain private. The couple has maintained a close friendship with Swift over the years. This strong bond is evident in their recent attendance at a stop of her Eras Tour in Spain, along with their three eldest children.

Swift’s friendship with the Reynolds family extends beyond casual hangouts. During the concert in Spain, she gave a heartwarming shout-out to the couple’s daughters. While introducing her album “Folklore,” she mentioned the names James, Inez, and Betty, sending the audience into a frenzy. This sweet gesture further highlights the special bond between the singer and the Reynolds children.

This isn’t the first time Swift has incorporated the girls’ names into her music. Her 2020 album “Folklore” features a song titled “Betty” that tells a story of a love triangle involving characters named James, Inez, and Betty. Additionally, her 2017 album “Reputation” included a voice recording of James on the song “Gorgeous.”

Whether Swift truly babysits for the Reynolds family or not remains a playful mystery. However, one thing is certain: the singer holds a special place in the hearts of the Reynolds children and their parents.

Media

The Simmering Feud Between Eva Mendes and Rachel McAdams

The 2004 romantic drama “The Notebook” continues to be a pop culture phenomenon, captivating audiences with its passionate love story between Noah and Allie, played by Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams. But beyond the on-screen romance, rumours of tension between the actors and Gosling’s current partner, Eva Mendes, have added a layer of intrigue to the film’s legacy.

From Clashing Personalities to Real-Life Romance

While their undeniable on-screen chemistry led to a blockbuster performance, Gosling and McAdams reportedly had a tumultuous time during filming. “We inspired the worst in each other,” Gosling admitted to The Guardian. However, their initial animosity blossomed into a real-life romance in 2005, sending shivers down the spines of fans who had rooted for Noah and Allie.

Love Found, Love Lost

Their off-screen love story, however, wasn’t a fairytale. After two years, the couple went their separate ways. McAdams found happiness and a family with screenwriter Jamie Linden, while Gosling met his current partner, Eva Mendes, on the set of “The Place Beyond the Pines” in 2011. Together, they have built a life and share two daughters.

A Post-Breakup Conundrum: Maintaining a Friendship

While McAdams and Gosling’s romantic flame fizzled out, reports suggest they remained amicable post-breakup. This friendly dynamic, however, is said to have shifted when Mendes entered the picture.

A Shadow of Jealousy? Unconfirmed Rumors of Tension

Unverified reports claim that Mendes is allegedly uncomfortable with McAdams being around Gosling. Unnamed sources allege that Mendes discourages any interaction between the former co-stars, fearing it might upset her. This has reportedly limited Gosling’s ability to maintain a casual friendship with McAdams.

The validity of these claims remains shrouded in mystery. Mendes and Gosling are known for their privacy, making it difficult to separate truth from speculation.

Beyond the Rumors: The Power of “The Notebook” Endures

While the rumors of off-screen tension add another chapter to the “The Notebook” narrative, the film’s enduring power lies in its timeless portrayal of love and loss. Whether Gosling and McAdams remained friends or not doesn’t diminish the on-screen magic they created. The film’s ability to resonate with audiences continues, reminding us of the intensity of first love, the pain of heartbreak, and the enduring power of memories.

The Notebook’s legacy is a complex one, weaving together a captivating on-screen love story, rumored off-screen tension, and a reminder of the film’s lasting impact on pop culture.

-

News4 hours ago

News4 hours agoAfter grind of MLS regular season, Toronto FC looks forward to Leagues Cup challenge

-

News18 hours ago

News18 hours agoCanadaNewsMedia news July 26, 2024: B.C. crews wary of winds boosting wildfires

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoOntario expanding access to RSV vaccines for young children, pregnant women

-

News5 hours ago

News5 hours agoIn President Milei’s sit-down with Macron, Argentina says the leaders get past soccer chant fallout

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoFrench train lines hit by ‘malicious acts’ disrupting traffic ahead of Olympics, rail company says

-

News18 hours ago

News18 hours agoPeople should stay inside, filter indoor air amid wildfire smoke, respirologist says

-

News12 hours ago

News12 hours agoFederal grand jury charges short seller Andrew Left in $16M stock manipulation scheme

-

News3 hours ago

News3 hours agoUmicore suspends construction of $2.76B battery materials plant in Ontario