Art

She was a ‘supermodel’ of the Pre-Raphaelite period. Now art historians are course-correcting the short life of Elizabeth Siddal

|

|

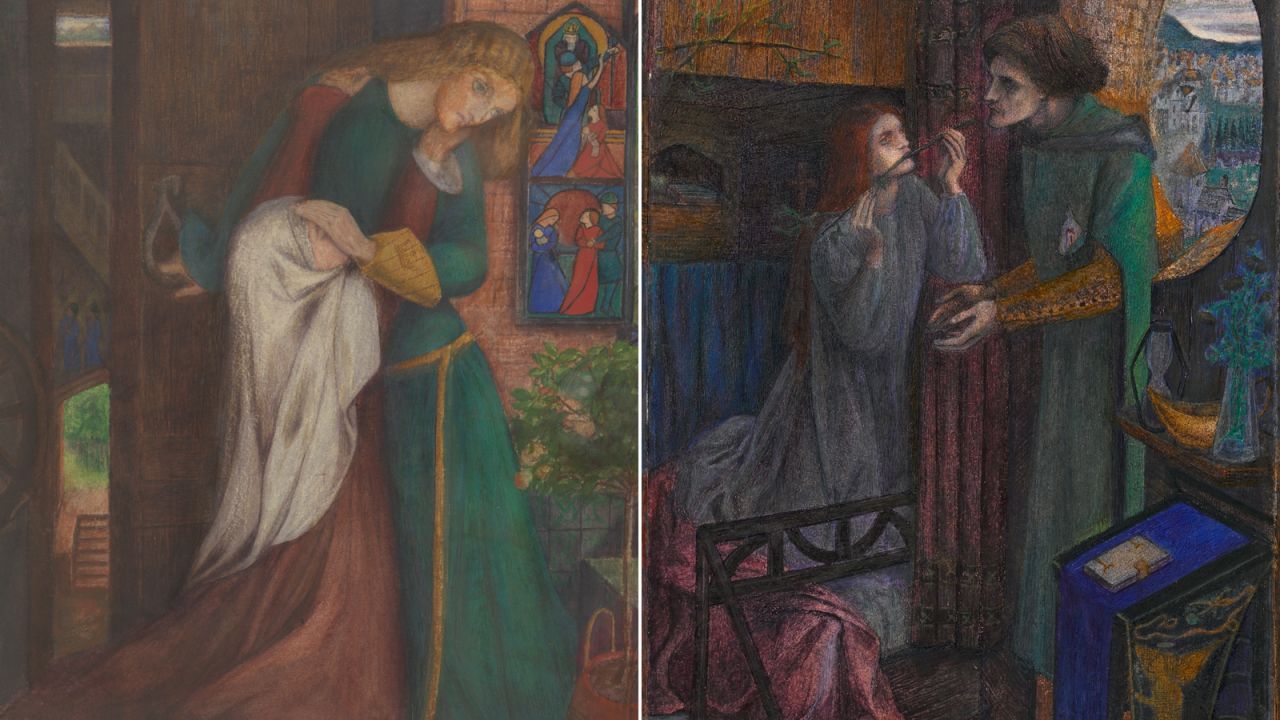

Even if you’re not familiar with Elizabeth Siddal, you likely know the 19th-century paintings she modeled for, artworks in which she slipped into others’ tragedies.

There’s Siddal as Ophelia drowning in the lush riverbank among forget-me-nots, or as the poet Dante Alighieri’s dying beloved, glowing with the ecstasy of reverie. You’ve perhaps also heard the melancholic retellings of Siddal’s own arc: muse with a turbulent love life; fragile health; life cut short at 32 due to the opiate laudanum poisoning her blood.

But you might not know Siddal’s own groundbreaking work as an artist and poet: her vibrant, emotionally expressive paintings, or her ballads of yearning. A new exhibition at the Tate Britain in London, “The Rossettis,” seeks, in part, to change that. The show, which focuses on Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who became her husband, his poet sister Christina, and Siddal, brings together more than 30 of Siddal’s works, the most seen together in 30 years.

Siddal was the only woman to exhibit work with the short-lived but highly mythologized Pre-Raphaelite movement, which formed in 1848 and prized the period of 15th-century Italian artmaking that saw the medieval era give rise to the Renaissance. And though Siddal later became known for her modeling — for Rossetti, John Everett Millais and other artists — scholars and curators are shifting the attention to her rarely shown surviving art, which numbers some 60 works on paper and a handful of paintings. (Some of her lost works are shown for the first time at the Tate through photographs taken after her death).

Tate curator Carol Jacobi says both the “physical fragility” and sparse number of works have led to few shows dedicated to Siddal. “But it is also the fact that she is very much eclipsed by the much more famous artists that were around her,” Jacobi explained in a video call. “And we cannot deny that, particularly for historical women artists, it’s still a bit of a battle.”

Siddal’s works eschewed realism and delighted in beauty and fantasy. Her art often depicted emotionally charged scenes from poetry, like the jewel-toned painting “Lady Clare,” based on an Alfred Tennyson ballad in which the titular character finds out her life has been a lie. In another piece, “The Macbeths,” Siddal paints herself and Rossetti as the ill-fated couple, driven mad by prophecy.

Most of the artist’s works are watercolors and drawings. Her only known oil painting — a delicately rendered self-portrait on a circular canvas — is among those lost to time.

Getting her due

Reframing the focus on Siddal as a pioneering artist in her own right, rather than on her proximity to male luminaries, is an overdue course-correction. It’s also one many institutions are taking with famous “muses” of art history; photographer Dora Maar, who rose to fame as Picasso’s “Weeping Woman,” and painter Suzanne Valadon, who danced across Renoir’s scenes, are two such artists who have received important retrospectives in the past handful of years.

In Siddal’s case, this path to recognition has not been linear. Curator and scholar Jan Marsh has been championing Siddal as a key member of the Pre-Raphaelites since the 1980s, when feminist theory overhauled frameworks around women artists. (Marsh has contributed an essay to the exhibition catalog). Still, myths and misconceptions about Siddal persist, as the ingredients of a tragic heroine’s life fill in the gaps of knowledge around her.

“A lot of the stories that are told about Elizabeth are not really stories about Elizabeth — they are stories about Dante Gabriel: his love affair and the inspiration of his art, and the Elizabeth that he creates in his poems and his pictures. And so she gets eclipsed in lots of different ways,” Jacobi said, pointing to the fact that much of what is known about Siddal comes from Rossetti biographies. “I think it’s still really hard to get at that real person.”

Television and film interpretations have run with this narrative, from the 2009 BBC miniseries about the Rossettis called “Desperate Romantics,” to the 1967 drama centered on Dante Gabriel, “Dante’s Inferno.” The Ken Russell-directed film, which begins with Siddal’s exhumation, “distills the mainstream idea of Elizabeth, and how powerful the ‘haunted woman’ is as a myth,” Jacobi said.

Before her time

Siddal deserves more than the oversimplified tales about her life. Though she had several months of art schooling and intentionally pursued her creative development, the myth that she was simply discovered by the Pre-Raphaelites while working in a hat shop has stuck, taking away her agency, as Jacobi and Marsh point out. Her physical maladies and opiate addiction have also likely been exaggerated. (Being in fragile health was a gendered cultural signifier in Victorian times, and laudanum, then a sleeping agent and painkiller, was a cure-all for everything.)

Even her death, speculated as suicide, is poorly understood. Marsh writes Siddal more than likely died from an opiate overdose while in post-partum psychosis after her daughter was stillborn, but that there has been little concrete evidence she was an addict.

And while many art historians have waved away Siddal’s work as largely influenced by her husband, Jacobi says they often worked collaboratively, and that he was taking just as many ideas from her.

Her prescience might have been more readily apparent had Siddal lived to see the next era of art unfold — one that she influenced without her knowledge.

In one of her drawings, “Lovers Listening to Music,” from 1854, she abandons any narrative in a scene of an affectionate couple — likely based on herself and Rossetti — serenaded by two figures with instruments.

“It’s very unusual because there is no story; it is simply a mood, a reverie of love,” Jacobi said.

Three years later, Dante Gabriel repeated the musical motif in “The Blue Closet,” which is presented in the Tate’s exhibit adjacent to Siddal’s drawing. His painting in turn greatly influenced the artist William Morris, a key figure in the aesthetic movement, which reveled in beauty and art for art’s sake, rather than realistic scenes of life or moralizing allegories.

In hindsight, there’s a “direct genealogy” from Siddal’s approach to aestheticism, a movement which included artists such as James Whistler and Aubrey Beardsley and writers such as Oscar Wilde, Jacobi said. “But of course, she wasn’t part of that story, because she died.”

Through “The Rossettis,” Jacobi would like to put forth the real narrative of Siddal: A working-class woman who struck out to be a painter and poet during a highly restrictive era for someone of her gender and social standing. Her work, like that of many women creatives, was not exhibited by mainstream institutions — the Royal Academy of Arts, at the time — and in fact, she rebelled against their tastes.

“She was painting in (her) own way… largely self-taught — that is the story of a modern artist,” Jacobi said. “And I think she was just 30 years before her time.”

Top image: Rossetti’s portrait of Siddal as Beata Beatrix. The painting, of Beatrix’s death, is based on Dante Alighieri’s 13th-century poem “La Vita Nuova.”

Art

Richmond art exhibits travel back in time, explore legacies

|

|

Two new exhibitions coming to Richmond Art Gallery (RAG) are travelling back in time in search of the meaning of legacies.

Starting April 20, community members can check out Unit Bruises, featuring artworks by Theodore Saskatche Wan and Paul Wong, and The Marble in the Basement, which pays tribute to iconic Canadian artist Joyce Wieland.

Unit Bruises, guest curated by Michael Dang, showcases performance artworks by Wan and Wong from the 1970s addressing societal issues including anti-Asian hate that continue to resonate to this day.

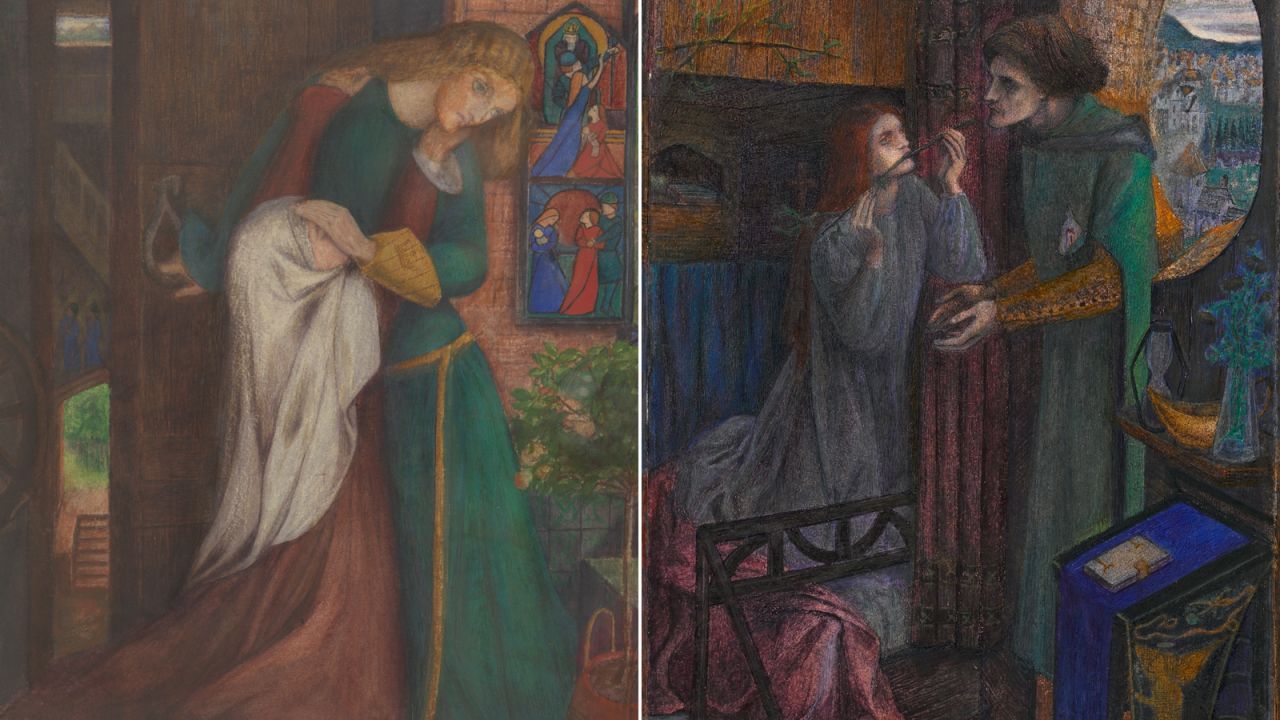

Named after Wong’s 1976 collaborative work with Kenneth Fletcher, 60 Unit; Bruise, where the two documented the ritual of withdrawing Fletcher’s blood and inserting it into Wong’s back via a syringe, the exhibition will also include Wong’s photographic series 7 Day Activity from 1977.

Blood Brother, a companion piece to 60 Unit from 1976 originally thought to be lost and re-edited in 2024, will also be featured.

Wan’s Bound by Everyday Necessities II, where he performed as a patient in a series of medically accurate photographs, will be showcased along rare objects from his archive including original drawings, handwritten notes and photocopies of medical manuals.

Wan is known for his black and white photographs “that straddled the line between instructional medical illustrations and Photoconceptualist interventions.”

Pieces featured in Unit Bruises are on loan from the Vancouver Art Gallery and private collections of Paul Wong Projects and Sophie and Christos Dikeakos. The exhibit, intended for mature audiences, is part of the 2024 Capture Photography Festival Selected Exhibition Program.

The Marble in the Basement, a solo show by Hazel Meyer and curated by Zoë Chan, is a continuation of Meyer’s research project into the legacy of feminist artist and experimental filmmaker Joyce Wieland that began in 2019.

“What gets stored in a shoebox? Deposited into an archive? Shoved into a corner? Catalogued as important?” wrote Meyer.

The gallery will be transformed into a basement in reference to a pile of marble scraps found in Wieland’s basement after her death and feature an installation of sculptures, drawings, video and a textile work.

In addition to the immersive installation, Meyer and her collaborators, including a cute bug-eyed puppet named Marble, will activate artworks and objects on display with three site-specific performances.

Through the project, Meyer explores the questions surrounding artistic value, inheritance, collecting, queer kinship and official histories.

The exhibitions will run from April 20 to June 20 at RAG.

Art

DC Knights call for Rupnik art removal

|

|

A Washington, D.C., Knights of Columbus council has called for chapel mosaics created by disgraced artist Fr. Marko Rupnik to be removed from the area’s St. John Paul II Shrine, which is sponsored by the Knight of Columbus fraternal organization.

The Cardinal O’Boyle Council 11302 passed a resolution April 9 calling on Knights leadership to remove Rupnik’s artwork from the shrine’s Redemptor Hominis Church and the Luminous Mysteries Chapel.

The resolution notes that Rupnik has been accused of sexually abusing religious sisters in the context of creating his works of art.

“O’Boyle Council calls upon the executive leadership of the Washington, DC State Council of the Knights of Columbus (State Council) and the executive leadership of the Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus (Supreme Council) to renovate the Shrine such that the mosaics in both the Redemptor Hominis Church and the Luminous Mysteries Chapel created by Fr. Rupnik are removed and replaced with liturgical art suitable to the celebration of the sacraments,” says the resolution, which was obtained by The Pillar.

The council calls on Knights national leadership to immediately publicize a plan for a removal of the artwork and to cover the images until a full renovation can begin.

“O’Boyle Council calls upon the executive leadership of the Washington, DC State Council and the executive leadership of the Supreme Council to immediately make a public apology to survivors of Fr. Rupnik’s abuse for the Order’s continued inaction in addressing the matter of the mosaics in the Shrine,” the resolution adds.

Rupnik is a well-known Slovenian priest, an artist, and a former member of the Jesuit order, the Society of Jesus.

The priest is at the center of a multi-faceted sexual abuse and cover-up scandal. Rupnik has been accused of spiritually, psychologically, and sexually abusing consecrated women in a Slovenian religious community. He was also briefly excommunicated in 2020, for attempting to sacramentally absolve a woman after a sexual encounter with her, a major crime in the Church’s canon law.

An initial examination of the allegations against Rupnik met a dead end when the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) declined to lift the statute of limitations on the allegations.

Amid widespread criticism, Pope Francis in October 2023 waived the statute of limitations on the claims against Rupnik, reopening the case against the priest, and allowing him to face a canonical process.

The DDF is currently investigating the allegations. Five new complaints of abuse were filed with the dicastery earlier this month.

The allegations against Rupnik have led to calls for the removal of his artwork, which is prominently featured in sacred spaces around the world, including the Basilica of the Sanctuary in Lourdes, France.

In December 2022, the Knights of Columbus said it was “reconsidering the place” of Rupnik’s work in the organization’s chapels. The Knights have already removed Rupnik’s art from their evangelization booklets and other published materials.

The O’Boyle Council resolution cites Sacrosanctum concilium’s exhortation that works of art which are “repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety” should be removed from sacred spaces.

“[T]he mosaics created by Fr. Rupnik in the St. John Paul II Shrine are repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety due and lack artistic worth due to the fact that Fr. Rupnik reportedly perpetrated his sexual abuse through the creation of his artwork,” the resolution states.

Rupnik’s mosaics are also featured in Holy Family Chapel, at the Knights of Columbus’ headquarters in New Haven, Connecticut.

The Knights of Columbus did not respond to The Pillar’s request for comment on the O’Boyle Council resolution.

Comments 26

Art

Canada's art installation at Venice Biennale rooted in research, history, beauty – CityNews Toronto

Hundreds of thousands of tiny glass beads will soon be twinkling in the sun across the entire Canadian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Canada’s newly revealed entry in one of the world’s most prestigious art fairs.

But Kapwani Kiwanga, the Hamilton-born, Paris-based creator of the work, wants you to get past the cobalt blue glass glinting in the Venetian light. She wants you to think of each bead as a character.

“The materials are documents of themselves,” she says. “They’re witnesses.”

The beads used in her installation “Trinket” were made on the nearby Venetian island of Murano. Centuries ago, similar beads were used all over the world as both desirable trade goods and currency in themselves.

Their name, “conterie,” comes from the Portuguese word for “count.”

“I never use (materials) just because they’re esthetically pleasing,” Kiwanga says. “That comes into it at one point but it’s really their social, cultural and economic history that makes me want to settle on a material.”

Kiwanga’s installation at the Canada Pavilion was revealed Tuesday, more than a year after she was named Canada’s representative to the 60th Venice Biennale.

Kiwanga has previously installed works at art galleries and fairs from Saskatoon to Dublin and London to Istanbul.

She has won major art prizes in Canada and France, and bagged nominations from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts for her film work.

Throughout all that work, she says, runs her interest in what materials have to say for themselves.

Sometimes, plants do the talking. One of her previous installations, “Flowers for Africa,” uses familiar flowers like gladioli that originated in Africa.

They may look arranged for a posh wedding or upscale hotel lobby, but are recreations of flower arrangements created for diplomatic events linked to independence negotiations for African countries. The arrangements gradually wilted, evoking emotions about the passage of time and the fleeting nature of pomp.

In other works, colours speak to the audience.

“Linear Paintings” explores hues believed to promote certain moods and used by industrial designers to cover walls in offices, mental health hospitals and prisons.

“I’m thinking of them as characters who have witnessed a past event,” Kiwanga says. “History is a starting point for a lot of my work, although I’m thinking about our present and sometimes our future as well.

“My larger question or interest is power and power dynamics.”

She wants viewers to consider her work a kind of “gateway.”

“I’m not trying to prove anything. I’m not looking for materials that prove a point. I’m just saying the who or the how or the what,” she says.

The work begins with a vague notion of something interesting that sheds a bit of light on how the world operates.

Then it’s study time. Popular and academic works on the theme are consulted, experts are interviewed, archives combed. She says about 60 per cent of the work needed to create a new piece is done in the library, not the studio.

Kiwanga credits her anthropology degree from McGill University with giving her the research skills necessary to her artistic practice.

For her sense of the world, she gives some credit to Hamilton. She now divides her time between Canada, France and Tanzania, but it was Steeltown that first showed her the world is a big place.

“Growing up in downtown Hamilton was quite diverse,” she says.

“In my Grade 1 class — I remember this — we had people from all over the world, some of whom had just arrived. The world already was in this tiny little bit of my reality.”

Being chosen to represent Canada at the nearly 130-year-old Venice Biennale “was a great honour,” she said.

Canada has been represented at the art fair since 1952. This year’s version will see 63 countries participating.

Previous Canadian representatives have included illustrious artists such as Alex Colville, Michael Snow and Stan Douglas — and that creates a certain pressure, Kiwanga admits.

“One person is chosen every two years, but there are so many other artists who could have been chosen and done something amazing. I felt a responsibility.”

But just being part of a global art conversation will be a highlight, Kiwanga says. And true to form, she’s already thinking of the Biennale as another kind of document.

“When we’re all together and we end up finishing our works, what’s it going to say about this moment?”

The Venice Biennale international art exhibition runs from April 20 to Nov. 24.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 16, 2024.

Bob Weber, The Canadian Press

-

Sports5 hours ago

Sports5 hours agoTeam Canada’s Olympics looks designed by Lululemon

-

Real eState13 hours ago

Search platform ranks Moncton real estate high | CTV News – CTV News Atlantic

-

Tech12 hours ago

Motorola's Edge 50 Phone Line Has Moto AI, 125-Watt Charging – CNET

-

Investment21 hours ago

Investment21 hours agoSo You Own Algonquin Stock: Is It Still a Good Investment? – The Motley Fool Canada

-

Science16 hours ago

Science16 hours agoSpace exploration: A luxury or a necessity? – Phys.org

-

News24 hours ago

Federal budget will include tax hike for wealthy Canadians, sources say – CBC.ca

-

Investment19 hours ago

Investment19 hours agoGoldman Sachs Backs AI in Hospitals With $47.5 Million Kontakt.io Investment – BNN Bloomberg

-

Health15 hours ago

Health15 hours agoUpgrading the food at VGH for patient and planetary health