For decades, developer Martin Selig has defied the odds in the downtown Seattle office market, profiting handsomely in the high times and managing the lows well enough that he still owns almost a tenth of downtown’s office space.

But the aftermath of the pandemic is testing Selig’s resilience in ways that underscore just how different the current crisis is from past office downturns.

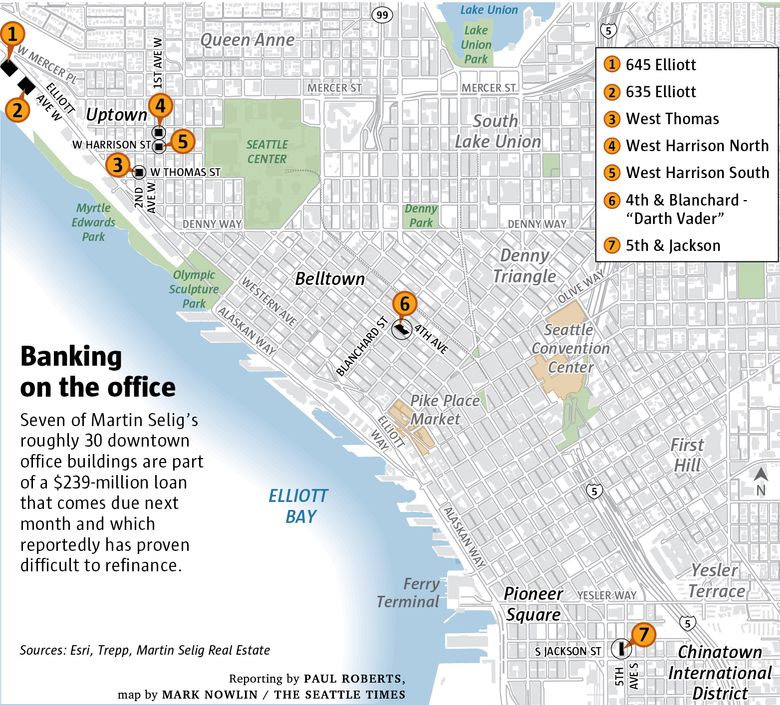

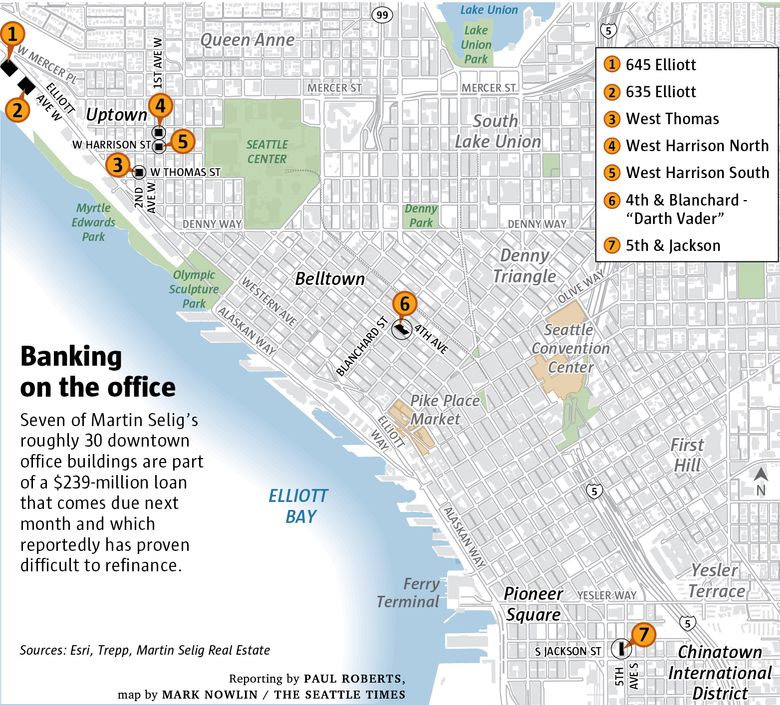

On March 20, a $239 million loan backed by seven of Selig’s roughly 30 downtown office buildings was transferred to a so-called special servicer and flagged for “imminent maturity default,” according to Trepp, a commercial real estate data firm.

Imminent maturity default is a term used when borrowers are expected to be “unable to repay the loan in full upon its maturity,” said Stephen Buschbom, Trepp’s research director. Special servicers typically oversee loans in default, at risk of default or requiring modification.

Selig’s company, Martin Selig Real Estate, hasn’t missed any of the $950,000-a-month, interest-only payments on the loan, whose collateral ranges from a four-floor building near Elliott Bay to the 25-floor Belltown building nicknamed “Darth Vader” for its dark glass and diagonal roof line.

But the move to a special servicer suggests Selig may face challenges in repaying or refinancing the loan principal, which comes due May 6, said Buschbom.

The move to special servicing was also “somewhat anticipated” because the loan properties have experienced rising vacancies and declining rental income, which makes “it very difficult to refinance the current debt,” Buschbom said.

Between 2019 and 2023, average vacancy in those buildings rose from around 4% to around 27%, while average monthly net operating income fell from $2.1 million to $1.6 million, according to Trepp.

The data is public because Selig’s loan was “securitized” and sold to investors, a process that requires borrowers to file regular reports with federal regulators.

For comparison, overall vacancy in downtown Seattle was around 26% in December and has since hit 29%, according to Cushman & Wakefield, a commercial real estate firm. That’s even worse than during the Great Recession, when downtown Seattle office vacancy reached around 21%, according to contemporary accounts.

Martin Selig Real Estate declined to comment on the status of the loan, share any specific company data or confirm outside assessments by Trepp or others.

But in a detailed statement this week, the company offered what appeared to be an acknowledgment that it’s working on a refinance.

It noted that many securitized office loans today have moved to special servicers, in part because servicers handle the loan modifications that are “a required step in the renegotiation process that many borrowers are currently experiencing.” It also said, “our lenders continue to be supportive in reaching a positive resolution.”

Canary in the coal mine

Still, the uncertainties around Selig’s maturing office loan, one of several major loans held by the company, have reverberated through the Seattle market, in large part because Selig is hardly the only office landlord facing serious challenges.

In March, the share of securitized office loans in special servicing hit 10.3%, the highest rate since 2013, according to Trepp.

Not all of those loans are delinquent — around 6.6% of office loans were 30 days or more delinquent as of March, the most since 2017, according to Trepp. But many likely face refinancing deadlines: roughly a quarter of all office loans mature this year, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

Falling incomes coupled with today’s higher financing costs are putting pressure on landlords and their bankers, who must figure out how and whether to refinance buildings that are often worth less than when the original loans were made. Selig’s loan, taken out 10 years ago, has a 4.6% interest rate, according to Trepp; that’s well below current rates.

Office uncertainties are also creating problems downstream from landlords themselves.

Many of Selig’s businesses have racked up at least $8 million in delinquent bills.

There is an estimated $296,000 in city of Seattle permitting fees that Selig is paying down under a settlement with the Seattle City Attorney’s Office. Selig also has around $1 million in late Seattle City Light bills, according to records provided by the utility, down from $6 million owed in September 2022, according to the City Attorney’s Office, which said Selig has agreed to a payment plan.

Selig also has more than $3.6 million in delinquent fees for the downtown Metropolitan Improvement District, according to records provided by the city. In September, the City Attorney’s Office said Selig’s then-$2.7 million balance of unpaid district fees had been referred for collection but as of Friday hadn’t provided an update on the case.

Selig also had $3.4 million in delinquent 2023 property taxes on his Seattle offices and other properties, according to county tax records, as of Friday.

Contractors and others have also filed a number of liens and lawsuits alleging nonpayment of debts by various Selig companies.

“It definitely hurt us last year,” said Chris Chandler, who claims Selig is months behind on more than $120,000 for building security services provided by Chandler’s small security company, Chandler Solutions. “A couple months there we were close to not being able to make payroll.”

Selig’s company wouldn’t comment on specific debts other than to say it was “working with the respective agencies to promptly address these outstanding balances.” It did not respond to questions about Chandler’s claims.

A perfect storm

Selig has been on the ropes before in an industry as notable for its downs as its ups. In the late 1980s, Selig famously was forced to sell his prized Columbia Center, just four years after building it. (He made a substantial profit on the deal.)

Selig has filed for bankruptcy on individual properties, fallen behind on utility bills and become infamous for disputes with contractors.

He has always bounced back, thanks partly to very deep pockets. Despite a huge appetite for debt — around $1.2 billion in debt as of July, including a $379 million loan that matures in 12 months — Selig has always had substantially more equity. As of 2023, the value of his main office properties was around $1.8 billion, according to county tax appraisals, which are widely regarded as conservative.

But the post-pandemic office market has confronted Selig and other landlords with a combination of challenges that don’t have precedents from earlier downturns.

Notably, despite broad recovery of the economy, the normalization of remote work has contributed to stubbornly high office vacancies, which has meant lower incomes and falling property values.

Although tax assessments are conservative, it’s still telling that the assessed value of the seven properties in Selig’s maturing loan fell around 13% since 2019.

In the past, Selig has insisted that these are cyclical challenges and that the main factor in the lagging office recovery — remote work — is transitory. In a July interview, Selig predicted that most workers would be back in the office “five days a week” by the end of 2024.

In a statement this week, the company said it remains “optimistic” and that “more employees are returning to the office each day.”

As evidence, the company referred to data posted by the Downtown Seattle Association, showing the number of daily workers in downtown Seattle averaged 87,000 in March. According to the Downtown Seattle Association, that’s “the highest daily average for worker foot traffic since February 2020.”

The company also said it is “seeing an increase in leasing activity, including interest from a number of new, large users.”

But there is no shortage of data to support a less optimistic view.

The same Downtown Seattle Association report notes that March’s daily worker average was just 52% of the level in March 2019.

In fact, Seattle was recently ranked 40th out of 44 major U.S. cities in “post-pandemic performance of their central business districts,” in a recent study by The Business Journals, owner of Puget Sound Business Journal.

Some forecasters think Seattle’s downtown office market might not see significant improvement until 2026, said Steven Bourassa, chair of the Runstad Department of Real Estate in the University of Washington’s College of Built Environments.

But even then, given the overhang of empty offices, the city’s office “problem is not going to be solved in ‘26,” he added.

Indeed, even if downtown Seattle employers were to immediately bring back workers Monday through Friday and office demand jumped back to its pre-pandemic five-year average — around 2.2 million square feet a year, according to data from brokerage Cushman & Wakefield — it still would take around six years to fill the roughly 15 million square feet of space that is vacant or available for sublease.

As important, even as the market comes back, Selig will be competing for that limited demand with what many see as a major disadvantage: vintage properties.

The average age of Selig’s office portfolio is more than 30 years and around 36 for the seven buildings in the maturing loan. Selig has invested heavily in upgrades and renovations for all his properties — “Darth Vader,” for example, now has a fitness center and conference facilities. But the popularity of newer office buildings, dubbed the “flight to quality,” has accelerated during the pandemic.

According to a 2022 study by real estate services company JLL, office buildings that opened since 2015 have enjoyed rental rates that were 43% higher than rates for older buildings and also have seen lower vacancy.

Selig’s company candidly acknowledged that the “flight to quality is real, both in our own portfolio and globally” but insisted that steady building upgrades have ensured even its older properties “remain highly desired.”

Extend and pretend

Whether investors and bankers think so remains to be seen.

On Selig’s maturing loan, the properties’ rising vacancy rates and falling income might make bankers unwilling to refinance the full loan amount, Trepp’s Buschbom said. Instead, they might insist Selig “buy down” the loan as a condition of a refinance, he said,

Depending on how optimistic investors are, Selig’s “cash-in” requirement for a refinance could range from around $40 million to almost $100 million, Buschbom said.

In the Seattle commercial real estate community, similar calculations have led to speculation that Selig might have to sell off properties to meet those requirements.

Selig declined to share details about refinancing negotiations. In response to speculation about a sale, “the overall company strategy is to develop and hold the assets,” according to the statement.

Indeed, that growing pile of equity, coupled with the company’s long history, appears to be the basis for Selig’s optimism that it is “well-positioned to withstand this phase of the cycle.”

Still, Selig’s best case for optimism, paradoxically, may be everyone else’s pessimism.

With most of the office market struggling, lenders have little incentive to foreclose on partly empty buildings that would be virtually impossible to sell.

“No one’s going to want to buy these properties, except at a fire-sale price,” said UW’s Bourassa, referring to office buildings in general. In 2023, he noted, sales of downtown Seattle office properties were just $29 million, compared with $2.3 billion in 2022, according to Cushman data.

Already, lenders have been temporarily extending maturing office loans rather than foreclosing and hoping for a market recovery, according to The Wall Street Journal and other media reports. It’s a pattern some have called “extend and pretend.”

Bourassa expects that to continue. For lenders and landlords alike, he adds, the main strategy for the next year or two is likely to consist of a very basic, and extremely unexciting formula: “You’re going to be really patient.”

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.